You all have seen this commercial, right?

In case you can’t listen to this while you read our blog in your cubicle while you’re supposed to be working (for shame!), I’ll give you a rundown. A chef is lamenting, in song, the effect that Bertolli brand pasta sauce has had on the restaurant business.

I make-a lasagna

I take all day

My tables are empty anyway…

[a cry of rage and despair] Bertolli!

When I saw this commercial, it immediately reminded me of a similar one from a few years back, advertizing Barilla pasta. There’s no video of this one, unfortunately, but I remember the lyrics:

Love is grand

and love is good

but to Italians love is food

Barilla!

Both sets of lyrics are sung to the “Habañera” from George Bizet’s Carmen.

What are these commercials trying to do with this music? Click through, dear reader, click through!

Before we can tackle the music, we need to deal with the more basic question of what the commercials are doing to begin with. It’s a question with a simple answer: they’re trying to sell pasta. More specifically, they’re trying to sell pasta by evoking a certain “Italian-ness.” That’s not particularly strange on the face of it. After all, pasta comes from Italy, and if Americans are going to buy an Italian food product, they’re going to want one that is authenticly Italian.

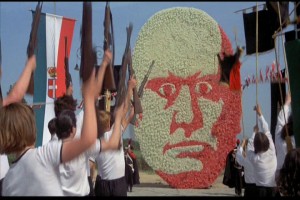

Mussolini might not have been very good at getting me to buy pasta, but at least he made the trains run on time.

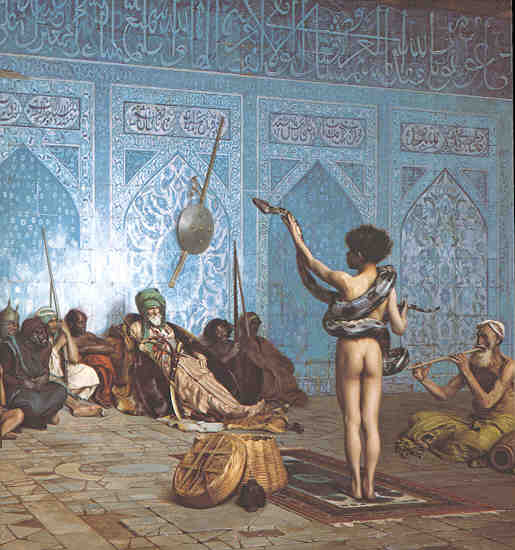

But of course there’s more to it than that. First, the Italy evoked here is a very specific Italy. It’s not, for instance, the Italy of Rome, The Godfather Part II, or Amarcord (left). It’s the Italy of The Olive Garden: an “Italy” for non-Italians. And what are the attributes of this phantom nation? It’s a place where everybody sings, where passionate (culinary) artists let out cries of grief and rage, where beautiful dusky-skinned women lick ragù alla napoletana from wooden spoons (from the Barilla ad), and where the entire populace is dedicated to the earthy pleasures of cuisine. It’s set up as an idyllic space, but also as fundamentally irrational and anti-modern. It is, in a very particular sense of the word, “Oriental.”

“The Orient,” – and it should be obvious here that I’m talking about the ideological construct, not about an actual place or group of people – is attractive, sexy, magical, and exotic, but fundamentally antagonistic and inferior to the forces of Modernism, Christianity, Patriarchy, and so on down the line. At its core, Orientalism isn’t about the “East” at all, but rather about giving the “West” something to define itself against. So if you’re not white, male, upper-middle-class, Christian-but-not-particularly-observant, heterosexual, healthy, gainfully employed, and from THIS country (whatever this country happens to be), you’re fair game. While Edward Said was only talking about depictions of Asia, we can find the same basic pattern in depictions of any political “other,” including the more “exotic” parts of Europe itself. Spain and Italy get “othered” a LOT. To a certain degree, this might be fallout from the reformation, with Protestant countries using comfortable orientalist slurs to dehumanize the “backward” Catholic nations… whatever the reason, it definitely happens, and you need look no further than the stereotype of the hot blooded and hot tempered Latin Lover for proof. (Notice that the disambiguation page takes you to both Italian and Hispanic actors. This is revealing! It doesn’t really matter what ethnicity your Latin Lover is. He’s the Other, that’s enough.)

The Olive Garden: When You're Here, You're Family

This is the archetype through which Bertolli and Barilla attempt to sell their food products. How does the music play into it? First of all, it’s opera. Within the classical music world, interestingly enough, Opera is faintly disreputable, attracting many of the same connotations – excess, mystery, the body – as Said’s “Orient,” and it’s possible that some of that carries over into mainstream representations. Outside of the classical music world, opera codes very strongly as “money, privilege, the elite,” another category that can help you sell things but is fundamentally opposed to the day-to-day lives of the consumer class. Finally, in any American context, its most potent connotation is foreignness. Is it specifically Italian? Well, what matters is that it’s absolutely unamerican. But sure, Italy does have a great operatic tradition, and using opera is a servicable way of evoking the nation. Bizet’s Habañera is perhaps the most instantly recognizable song from the most instantly recognizable opera in the entire repertoire, but it’s not the only one you’ll hear in commercials like this. I know I’ve heard Va Pensiero and O Mio Babbino Caro used to hawk parmesan and tomatoes, although I can’t seem to find the actual ads on youtube.

But what’s really interesting about the particular commercials under consideration here is that the Habañera is not Italian! Bizet was a French composer. His opera, Carmen, is set in Spain (c.f. the “Latin Lover” again), and the character Carmen, who sings the Habañera, is a Gypsy – and a woman – and thus marked even more strongly as different.* (The form her difference takes? She is sexual, irrational, exotic… we’re on familiar ground here.) Now, Bizet didn’t come up with this melody himself. It’s borrowed (i.e. stolen) from a popular Spanish folksong. Bizet used music he thought of as “Spanish” to dramatize Carmen’s difference to his French audience, just as Bertolli is using music we think of as “Italian” to dramatize lasagna’s difference to an audience of American pasta-buyers.

With me so far? There’s another layer. The Habañera folksong that Bizet cribbed from isn’t actually “traditional.” In fact it was written by the Spanish composer Sebastián Iradier. And he was imitating a popular dance genre from the Spanish colony of Cuba (which he had visited), which is where it gets the name “Habañera,” i.e. thing from Havana. Now I’ll come clean: I don’t really know a lot about representations of Cuba in Spanish culture. But can’t you pretty much guess? The queasy relationship that 19th century Europe had with its colonial territories is what prompted Said to write Orientalism in the first place!

Music is famously resistent to any kind of universal interpretation. Even distinctions as seemingly obvious as major=happy/minor=sad are actually subjective: the “meaning” of a series of notes is always the product of the listener’s culture. What fascinates me about these three cultural meanings of the Habañera is that they are so similar, but also mutually exclusive. People who understand that the song comes from a French opera about Spain find it laughable when its used to sell Italian food, and once you know about Iradier’s earlier version, you can’t ever really look at the version in Carmen the same way again. What is Iradier’s Habañera? Cuban? Gypsy? Italian? Or just irreducibly “ethnic”? This last may be the most convincing possibility. Take a look at the Habañera’s melody.

See how it’s based on a descending chromatic scale? Richard Taruskin has demonstrated that, within the context of European classical music, melodies of this type signify “not just the East, but the seductive East that emasculates, enslaves, renders passive,” and (I would add), sells pasta. In 19th century Russia – Taruskin’s specialty – this “East” referred specifically to central Asia. In 21st century America, not so much… but the broader significance of the melody seems not to have changed. It’s probably precisely BECAUSE its association with the exoticized “other” is so generic and poorly defined, that it has adapted so well and survived so long.

None of which changes the fact that watching that commercial made me hungry for Lasagna. Mangiamo!

* The Political Other need not be a political entity, it’s just that the term was cooked up by the kind of people who see all human activity as essentially political. Women get orientalized all the time. (Be on the lookout for arguments that run along these lines: “Women are so much more in touch with their feelings, you see! Men, on the other hand, can do math.”)

Said is like Kant- I can’t stand his writing, but what he has to say comes up SO OFTEN that I can’t escape it. The difference is, though, I (mostly) agree with Said’s point and think Kant was a nutter.

ANYHOO, ahem. Does the penchant for otherizing come from individuals and bleed into mass culture, or is it the other way around?

And is it orientalist, i.e. otherizing, in the “racist” form for an American to say, “I don’t like Russians because they’re from a corrupt government,” or, “I hate Saudis because they’re from a corrupt government,”? I think one of the tensions I found in _Orientalism_ that was never *quite* resolved for me was how there is a difference between racism and discrimination, as well as where that line is located at all. In the example I just gave, the former would be generally considered discriminatory and the latter as racist, even though the reason for disliking both is the same. This bothers me, because pulling the “racist” card shuts down SO MANY political debates and discussions that really NEED to be hashed out- or that would be a lot more enjoyable/productive if race was left out of the issue. (Easiest example: expressing any sort of disapproval for Israel’s political actions automatically makes a person antisemitic in the popular culture.) And no, I’m not saying they’re ABSOLUTELY mutually exclusive, but again, not every aspect of otherizing has to do with race (or at least as much as it ends up being made out to have), and forcibly categorizing something as such only makes matters more complicated.

I’m not disagreeing with anything, btw, just using you as a spring-board for my own overthinking.

God, I need a life…

Excellent post, btw.

Agreed, excellent, excellent post.

Gab, I understand the frustration about discussions getting shut down over race issues, but it does not at all follow, to me, that we can somehow discuss things which *do* include dimensions of race *without* acknowledging those dimensions. And, on some level, any modern American evaluation of Saudis has a “race” dimension to it, because if we have been acculturated in the culture of our time and place, it includes a well established context of orientalism/racism/many other things. The relationship to Saudi Arabia in this context is marked very strongly along essentialist lines, whereas the relationship to Russia in the wider culture, especially post-USSR, is marked less distinctly. I’m not saying there’s no Russia baggage, certainly not, but we admit their playwrights and their composers to our classical canons, and I’d say they’re much closer to “near, dear, weird” Others like Spain and Italy than they are to Saudi Arabia (just think about what “Arabia” summons up for us. A lot).

Also, I just googled subaltern. Tags=AWESOME.

When my orchestra was playing Mendelssohn’s 4th (the Italian Symphony), someone asked me which one it was, and the first thing that came to mind was, “It’s one of the pasta sauce ones.” I can’t put my finger on which sauce, or what time period the ads were from, but that first movement has definitely been used.

Mendelssohn’s Italian symphony (like his Scottish symphony) was the result of his travels around Europe. He wanted to bring the things he experienced around Europe to his audience in England (and Germany, I suppose, but he was writing this one for England), modeling the themes after the abstract joie de vivre (or whatever the Italians call it) of the people to the actual music of the dances he heard and saw.

Our conductor told us that Mendelssohn’s Italian symphony was basically the 19th century equivalent of an audible postcard.

So now, when someone wants to evoke an image of Italianness, nobody really goes for Italian composers. I’m not going to pop a disc of Vivaldi concerti in the stereo and sit back to imagine the rolling hills of Tuscany. In fact, our two examples were foreign composers who were writing ABOUT Italy (and in Bizet’s case, going at it in a rather roundabout way). That’s why I think your analysis about Othering is spot on: it doesn’t have to be Italian. It just has to be what the non-Other thinks of as “Italian.” And what better way to get at that than to use music that was originally written about Italy from the same perspective?

Anyone else think of this?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JhuOicPFZY

Siwi- I was just using an arbitrary comparison of two countries that come up in the news all the time as “corrupt.” Yeah, any discussion about Saudi Arabia is going to have to have race brought into it simply because of the nature of orientalism and how the west views the Middle East. And as such, I agree about how race shouldn’t be *ignored*, hence my admitting politics and race aren’t always mutually exclusive. My problem is when race is used PURPOSELY to disrupt the flow of debate/discussion. It’s a cop-out, for how can one really prove or disprove an accusation of racism? It’s pretty much impossible, so the discussion stops or gets totally screwed up/taken in a different direction.

Melanie: How about all of the Rome-inspired stuff by Respighi? Beautiful music, *and* he’s Italian.

Y’all are onto something here. I can only recall one commercial that used music by an actual Italian composer to convey an “Italian” atmosphere. The commercial is for an establishment called “Prince of Pizza” and it is set to “La donna e mobile” from Verdi’s “Rigoletto”. And it is a *fake* commercial, from the Prairie Home Companion movie.

It’s not just a pop-culture thing, either; this careless attribution of nationality still prevails in music theory classes. I never understood why they called certain augmented 6th chords “Italian” or “French” or “German”, nor why flat-II was called “Neapolitan”…

Re: spighi

The Pines/Fests/Fountains of Rome are interesting cases. You *don’t* see them used to sell pasta. (Now flying whales on the other hand…) It might it be revealing that Respighi wrote on the Pines of ROMA, not those of Italia. The military grandeur floating around the background of those pieces is potentially a wee bit disturbing… Listen to the “Pines of the Appian Way” movement from Pini di Roma again and remember that this music is coming out of Italy in 1924.

One wouldn’t want to overstate the connection. Respighi was largely apolitical, there’s also a big difference between Italy in 1924 and Italy in, say, 1936. Still, it gives you pause. (Gives me pause, at any rate.)

Oh, I definitely notice the big brass fanfares and such. John Williams seems to have taken vague inspiration from him, imo. But anyway, I still wonder why none of those pieces are used for pro-Italian or “Italian” ads. And what *if* the featuring of “Pines” (although it’s missing a movement… my favorite one, too) in _Fantasia 2000_ gives them the boost they need to get more popular, but used for all sorts of other stuff?

So on a related note: Gershwin in United Airlines ads. It has been there for as long as I can remember, but in the newer ones, it sounds, well, a bit orientalized- it takes longer to realize it’s “Rhapsody” because different instruments and style are used. Is THAT ok?