Argumentam ad Culum vs. The Space Whale Aesop. (Only One Involves a Probe.)

There is a literary device that TV Tropes calls the Space Whale Aesop. (I don’t know that it has any other name — as far as I know, they’re the only ones to describe it.) The Space Whale Aesop has to do with the handling of didactic morals. In a normal story, you convey the moral by showing the possible consequences of good and bad behavior: Gallant shows up on time to the job interview and gets hired, Goofus shows up late and has to go to graduate school, etc. In a Space Whale Aesop, rather than showing the possible consequences, the writers take advantage of a supernatural setting to invent some impossible consequences. The name comes from Star Trek IV: The Search for Whales*, where it turns out that if we don’t all start recycling, a race of literal space whales are going to blow up the planet, once again proving Arthur C. Clarke’s old adage that a sufficiently advanced cetacean is indistinguishable from lazy writing. And of course there are as many examples as one cares to name. By a certain way of thinking, every slasher movie ever has a Space Whale Aesop. “Don’t have sex!” “Why, because of the moderate risk that I’ll get pregnant?” “No, because of the virtual certainty that you’ll get axe-murdered.”

This episode of South Park actually did have a Space Whale Aesop, come to think of it. Think about it: why shouldn’t we lie to children? Because if we do, they’ll steal a killer whale and launch it into orbit. (More darkly, given the show’s semi-covert right wing stance: why shouldn’t we bother trying to save the environment?)

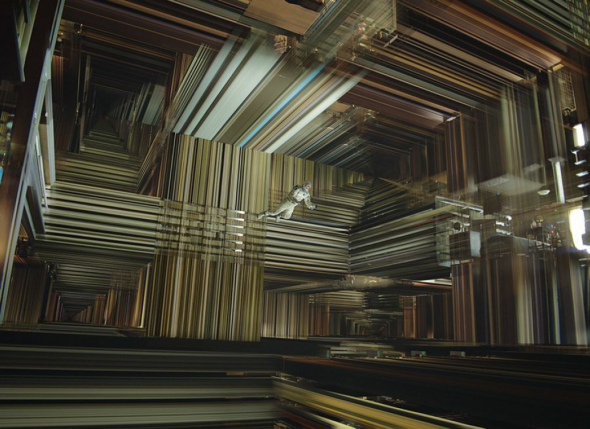

Now, I quite liked Interstellar. It’s a wonderful piece of technical filmmaking, and I wasn’t bothered by the little logical flaws that the podcast pointed out. What can I say, it worked on me. I loved the visual representation of the tesseract. McConaughey and Chastain had some heavy lifting to do in order to give it emotional heft, but they were up to the challenge, especially with the subtle assist that McConaughey got from Bill Irwin (the voice of the robot), and the incredibly blatant assist that both of them got from Hans Zimmer. As a movie, I think it was great.

But as an argument, it’s incredibly sloppy. And that’s a problem, because Christopher Nolan movies are usually arguments before they are stories. Towards the climax, my wife leaned over and whispered to me “This is beginning to feel like Signs.” I don’t know if she meant that as an insult — Signs is actually one of the better Shyamalan pictures — but if I’m Christopher Nolan and I hear that comparison, I start worrying. That is NOT the twist ending you want for your filmmaking career!

And the problem with Interstellar‘s argumentation is sort of like a Space Whale Aesop. But only sort of. Instead, it makes use of a closely related trope that I just invented to describe situations like this one: argumentam ad culum, i.e. winning an argument by pulling facts out of your ass.

Here’s how it works.

- Tell a story. The argumentam ad culum sounds like a logical fallacy, but it’s really a narrative technique. Most of the time.

- Next, have two characters in the story get into a debate about the fundamental nature of life, the universe, or humanity. For the technique to work, this needs to be a live issue, i.e. something that modern science has not really been able to resolve. No fair writing historical fiction where Magellan gets into a shouting match with some guy over whether or not the world is round.

- Optional, but recommended: structure your story so that a VERY great deal is riding on which of the characters is right.

- Finally, design the climax of your narrative so that something happens, more or less by magic, that proves once and for all that one side of the argument is right.

In Interstellar, the debate is over whether or not strong emotions such as love can violate the information-theoretical constraints of the theory of relativity. This isn’t explicitly addressed until about halfway through the movie, when they’re choosing whether to visit The Planet of The Matt Damons or The Planet of the Conveniently Deceased Love Interests. Hathaway posits — for NO reason that makes sense to me, or to any of the other characters — that they should visit her boyfriend’s planet, because her love for him somehow indicates that it’s the right call. Now, this seems like bunk on the face of it, and it’s not an argument that real-world scientists are planning to have any time soon. But it’s not really a decided question. We don’t know that it’s so, or that it isn’t so, until we run an experiment that proves it one way or the other. And since we haven’t actually done any manned missions to deep space, we haven’t tested it yet. (I can think of a way to do scaled-down tests in, like, a hedge maze… but I think one of the unstated implications of the events in the film is that this emotional spooky action at a distance only takes place over looooong distances. If your loved one is just on the other side of a wall of hay bales, whatever organ you’re supposed to sense them with would be overloaded by the strength of the signal. We should also note that non-human trials of this phenomenon have actually been done. I’ve mentioned it before on the site, I know, but I’ll say it again: have you all read up on Benoit’s Snail Telegraph?)

The movie makes everything ride on this debate. Not just the fate of the human race is at stake, but also the worth of the human soul. If Team Science wins this one, then we might as well just be animals: jumped-up monkeys, good for nothing but fightin’ and fu… uh, breeding. (Notice that Team Science’s choice takes us to the self-serving Dr. Mann. Symbolic Name Alert.) But if Team Humanities is in the right, then love is bigger than logic, and we are human after all — and therefore, in some small way divine. (Notice that towards the end of his trip through the n-dimensional bookmobile, McConaughey somehow intuits that the whole thing was put together by a super-advanced race of future humans.) What’s interesting about this formulation of the debate — and I’m not quite sure if this is a general feature of the argumentam ad culum or not, but I think it might be — is that it states the question in terms that only really make sense to one of the sides. In the real world, nobody is having this exact fight… but people have fights like this, and when they do, it’s very important to Team Humanities that Team Science be wrong. There needs to be a place in the world for emotions! There needs to be a place for human dignity! There needs to be more in heaven and earth Horatio than are dreamt in your philosophy! If it could be proved that emotions violate the laws of relativity (or that ghosts exist, or whatever), Team Humanities would claim this as a giant victory… but so would Team Science, actually. Because if it can be proved, then Team Science just learned something about emotions, or relativity, or ghosts, that they didn’t previously understand. (Like, this is how actual scientists would deal with the phenomenon at the heart of Interstellar. I don’t know if the Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal guy realized that this was a parody comic or not… he must have, right?) Team Science doesn’t even recognize the debate as a debate. Whatever the answer turns out to be, they just want Team Humanities to shut up so they can get back to the lab. “Okay, so love can escape a black hole’s event horizon, fine, good to know. Us jumped-up monkeys are gonna use that knowledge in the service of further fighting and breeding, though, just so we’re clear.”

But Interstellar is very much on the side of Team Humanities. So when McConaughey’s love for his daughter lets him transcends space and time, this is supposed to be a victory for the human spirit. Although the information he gives her allows for a scientific breakthrough, nobody studies the tesseract itself as a scientific phenomenon. It’s beyond that, get it? It’s soul-stuff. And knowing what we know by the end of the movie, if we backtrack to the argument that started it all, only the world’s biggest idiot would claim that Hathaway’s love for her boyfriend wasn’t a good enough reason to choose one planet over the other. When making important tactical decisions, human emotions are every bit as important as all the facts and figures and tables that science can come up with. Team Science is wrong. We have proof that this is true! You saw the movie, right?

That’s the argumentam ad culum. When the real world doesn’t provide you with the facts you need to make your case, write a story where “facts” come out of the woodwork. And although it’s not the most common literary technique, there are other examples. Short Circuit is basically just one giant argumentam ad culum on the question of artificial intelligence, for instance.

Oh, and before we move on: the difference between this and the Space Whale Aesop is that, with the Space Whales, the writers are trying to inspire action. They make up a scary consequence for some sort of bad behavior, hoping that the vividness of the storytelling will convince people to avoid the bad behavior even though the consequence isn’t real. If you pick your nose, you could nick a blood vessel and bleed to death! With the ad culum, the writers are apparently trying to inspire belief. It’s not a question of what we should do, it’s about what we know. (But it’s not like we actually gain knowledge from it! Again, it’s all down to the vividness of the storytelling.) And note that the argumentam ad culum does not apply to the very common science-fiction device of making some kind of bold claim about the nature of the universe at the start of the story and then working out all of the logical consequences. It should be reserved for cases where, at the climactic moment, the characters “learn” some totally made up fact with the same kind of wide-eyed awe that you would use in a Jonas Salk biopic for the moment where he figures out the polio vaccine.

I like how the tesseract is literally made out of stories.

We Need to Go Deeper

So far, so good. But maybe not so interesting. The reason that Interstellar is such a clear example of the argumentam ad culum is that the question they’re debating is so far-removed from actual human experience. “All right guys, which planet should the three of us visit first?” How could we ever relate to that decision? However, like most Christopher Nolan movies, Interstellar is heavily symbolic, maybe even bordering on allegorical. There are two possible interpretations that I’d like to consider briefly here, so we can see how the argumentam ad culum plays with each of them.

First, Interstellar is kind of a hymn to the glory of manned spaceflight. Which, we are told, is simply awesome. Not because of instrumental benefits like Tang and Velcro, but because of what it offers the human spirit: the chance to venture out into the great unknown, and touch the face of god. To explore. To dream.

The opposite of exploration, in Interstellar’s symbolic argument, is farming. (In my notes for this essay, I have scrawled in the margin “Interstellar, less movie; more, bizarre anti-farming Tract?”) As a farmer, you stay in one place, doing pretty much the same thing year after year. In real life, advances in agriculture happen all the time, but in Interstellar all farmers ever do is slowly lose their grip on what little they have. Mind you, many a farmer has done just that in real life. And the benefits of all those so-called advances are distributed pretty asymmetrically. But the economic foibles of late-capitalist agribusiness are the very last things on Interstellar‘s mind. The problem with farming is that farmers grub in the dirt when they should be reaching for the stars. (I think that’s literally a line in the film, isn’t it?) And this is why at the end of the film, when Jessica Chastain needs to get her brother out of the house for a couple of minutes, she does it by setting his crops on fire… not because it’s a reasonable or even a particularly effective plan, but because SCREW FARMS, that’s why! Farmers can run backward naked through a field of crops! And this is also why, just a little bit later, when her brother gets back to the house, covered in ash, and she’s standing there flush with the triumph of her successful communication with Space-Dad, he doesn’t start screaming at her, or smack her in the face, or pull his kid out of her boyfriend’s car, or any of the other things that one would expect his character to do. Instead, he just sort of collapses in on himself, because he’s a farmer, and somehow he knows in his puny farmer heart that she just proved that his entire worldview is based on a lie.

Weird, right, that farming ends up standing in for Team Science, while actual rocket science plays the part of Team Humanities?

But this argument is so sloppy. It is possible to make the case that even in a time of limited budgets and scarce resources, we should spend money on space exploration rather than on agriculture. You can even weigh exploration’s elevating effect on the human soul in the balance, if you want. What Interstellar does, though, is tell us that it’s established fact that if we keep farming, blight will eventually take all the crops and we’ll starve to death, whereas if we all sign up to work for NASA, we’ll get to go live in what looks like the deep-space equivalent of Mayberry. This is shading more into Space Whale territory. (You’re growing corn?! Do you want to DIE?!) But the argumentam ad culum comes back in when we consider what kind of space exploration we should do. Because really, didn’t NASA already decide that manned spaceflight is a little passé? It’s all about cunningly designed robots these days. They’re so much more effective, if what you care about is doing science stuff in space. But here’s the thing: although it was a pretty big triumph for the human spirit when they managed to land a robot on 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko a few months back, if your primary goal is giving people something to believe in (with science stuff in space running a distant second), manned spaceflight is still where it’s at. By inventing a world where human emotion can violate relativity, Nolan provides an argumentam ad culum for preserving “astronaut” as a viable career choice.

The second way to think about Interstellar is as an allegory for the creative process. This isn’t something that I’ve seen addressed elsewhere, although I haven’t really gone looking for it… which is surprising, because with Inception, that was all anyone could talk about. But where Inception is about the side of creativity that involves, like, creating stories and worlds and characters, Interstellar is about the other side of creative life: the side that involves essentially abandoning your children for months at a stretch so that you can spend the time cooped up in close quarters with Michael Caine and Anne Hathaway. We’re led to believe that this is a very good thing to do. The best thing! And again, there is a bit of a Space Whale aspect to the way that it plays out (what with the world being doomed if McConaughey stays home and drives his kids to soccer practice). But I don’t think that’s really the salient point. Suppose you are Christopher Nolan, and you get/have to do this super-demanding job that makes it incredibly hard to make time for your children. (Four of them!) And whatever the stakes may be for McConaughey, you know darn well that the world would not end if you walked away from your job tomorrow. If you’re that guy, in that situation… wouldn’t it be comforting to think that someday, when they’re older, your kids will watch the movies that you made and tell themselves “Wow, I know I was mad about it at the time, but that was a really worthwhile thing that Dad went off to do. And you know, somehow… somehow I got the feeling from the movie that he really did love us, after all? Like, maybe even more than our friends’ normal dads loved their kids.” If you’re Nolan, don’t you pretty much have to tell yourself that, just to get through the day? Well, Interstellar presents us with a world in which that scenario is objectively true. (Or at least allegorically objectively true.) That’s the biggest argumentam ad culum in Nolan’s whole film. But maybe it doesn’t matter if I’m not convinced by it… probably the only person he’s really trying to convince is himself.

* I also would have accepted Star Trek IV: The Wrath of Whales. ↩

I think you and I are largely in agreement about this movie, but while you would characterize it as “a mesmerizing piece of technical filmaking that made me forgive its storytelling shortcomings,” I would characterize it as “a mesmerizing piece of technical filmaking mostly ruined by sloppy/bizarre storytelling.” It reminds me a little of Lost, a show that early on set up a big “man of science/man of faith” dichotomy and eventually resolved it bigtime on the “man of faith” side of things. Instellar makes itself into a celebration of science… right up until the final act, when the whole thing becomes completely mystical and new-agey.

Signs is an excellent comparison – your wife is brilliant as usual. For starters, there are huge deux ex machina in both. In both cases the magical “love conquers all” ending is set up earlier, but they’re still hard to swallow. Also in this same boat is the ending to I Am Legend. I’m definitely in the camp that thinks the ending completely ruins the movie (there’s an alternate ending online that’s both more faithful to the book and not a deux ex machina, and it would have been way better).

Your theory at the end about the whole movie being about the creative process is fascinating. Makes me wonder what Nolan’s kids think about his work. Are they bitter about him being gone for months at a time? And what about his wife? Sure, in the movie the wife is dead, but given how Jessica Chastain spends most of the film as a grown woman I wonder if she becomes a stand-in for his wife in a way.

I liked that they went to a Water Planet, then a Cloud (Air) Planet, then Anne Hathaway settled on the Earth Planet. (Presumably they ruled out the Fire Planet out of hand.) Does this have any symbolic significance related to Planet Heart/Dead Boyfriend and Planet Science/Will Hunting?

Yes! “Earth” anagrams to “Heart”.

Also “Hater”, interestingly.

I liked this article because it pointed out a problem I had with that whole debate in the middle of the movie. It seems a somewhat pedantic and perhaps indicative of the oft spoken problem of Nolan’s female characters in his films and how they seem to serve only as love interests, villains or to die (in the case of Memento, all three.)

It’s very strange because the way the film treats Hathaway’s character (or perhaps its just the subjective nature of the acting) makes it seem like her ideas are barely important or to be relegated to the kind of anachronistic “female hysteria” that bad psychologists would diagnose a century ago. On a similar vein, the film’s only black protagonist barely has any character development and, much like the problems with female characters, is relegated to die because of a plot point designed to make the situation more difficult for the characters. This bugs me in particular because the black scientist dies but the robot lives. This sounds like some kind of bad joke. Again, the movie seems to emphasize something cold and logical over the personalities and interests of individuals.

Yet the film goes on to show that Hathaway’s character was right and that if they had chosen her preferred planet, the plan might actually have worked as originally intended, without the addition of two dead scientists or a half ruined spaceship. Of course this also proposes that the events which lead Space McConaughey to understanding gravity and informational teleportation through space-time would not have occurred and the movie would not have been fulfilled to the director’s vision.

Well, Hathaway was right insofar as her choice of planet goes… if you are just look at the habitability of the planet. But insofar as she may have picked it out of love, she was totally wrong. Love led her to a lonely dead end at the end of the universe. (Interesting how the 1 in a million reunion works out for McConaughey, but not for Hathaway.)

I’m having trouble figuring out what the message here is. Do we believe that she picked the planet completely objectively, as she claimed? But if so, what was the whole point of love being a mystical force that cannot be denied? But if she picked the planet because she wanted to be with the man she loves, and that guy was dead all along, what does that say about the power of love? Or is the point that dead or alive, the love she had led her to where she needed to be?

I think the best interpretation is simply that she’s good at her job and picks the correct planet for legit scientific reasons, and McConaughey was a dick for questioning her professionalism. But Nolan clearly doesn’t want us to think that since he gave her a rediculous speech about the power of love.

“Love led her to a lonely dead end at the end of the universe.”

Well, they did waste over fifty years using that black hole as a slingshot, so maybe the love interest died in those fifty years?

I’ve heard people complain that inception ends on the shot of the spinning top, cutting abruptly to the end credits without revealing whether or not it was a dream.

The end credits ARE the reveal. They’re a twist ending.

“It’s not a DREAM, it’s a MOVIE! You’re IN A THEATER WATCHING A MOVIE.”

So Mal and Cobb were both wrong. But Mal was certainly closer to being right.

So…. What if Hathaway’s boyfriend didn’t love her as much as she loved him? Must the attraction be the same in both directions for the “magic” to work? What if her love is completely unrequited? I’m picturing lots of people suddenly being able to warp to the Planet of Chocolate….

“And this is why at the end of the film, when Jessica Chastain needs to get her brother out of the house for a couple of minutes, she does it by setting his crops on fire… not because it’s a reasonable or even a particularly effective plan, but because SCREW FARMS, that’s why!”

I saw this particular narrative event as a symbol representing the unwillingness to leave home/Earth despite the inevitable destruction/death on the horizon. The house is Earth and the farms are a symbolic extension of earth’s resources. The stubborn farmer is unwilling to leave his home until it becomes apparent that his last resource is going up in smoke. The fact that this distraction worked in the story makes it somewhat effective, but definitely not reasonable. Perhaps Chastain’s “screw farms! moment is akin to a fringe environmentalist mentality that WANTS humanity to use up all the fossil fuels so we’ll be forced to figure something else out.

I also second your wife’s comparison to Signs. I had the same thought at pretty much the same time in the theater.

Also, someone above mentioned the lack of a fire planet in the film. With global warming/climate change/wildfires breaking out all the time, perhaps Earth is the fire planet.

You know what just occurred to me? Pretend you were the President. Option A is putting all our resources into biological engineering crops that can resist the blight. Option B is developing anti-gravity technology that can float the human race into space, through a wormhole, and onto a new planet.

I’m willing to let that one slide, but couldn’t they have come up with a more clear-cut “the planet is doomed” scenario?