Performance artist.

Realism vs. legitimacy

No, this isn’t a discussion of Kissinger and international relations, though if you want to start one of those, hop in on the comments and I’m sure Sheely will oblige you.

One trap with The Hurt Locker is to praise it for being “realistic.” It’s historical fantasy fiction – it doesn’t attempt to portray events that may have conceivably happened in real life. Oh, it has a certain authenticity in its setting and art direction, and it’s representational most of the time rather than presentational – meaning that the performance style is meant to draw a connection to how things might appear in life rather than use a more abstract vocabulary of symbolism. (The scene where the guys wrestle in the barracks is representational – the scene where the spent round falls from the sniper rifle in slow motion and bounces reluctantly, as if repelled from a hostile earth, is presentational. Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, where they travel through history, is representational, Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey, where they travel to the afterlife, is presentational.)

From what I’ve learned talking to guys who were over there, it gets certain things right that you don’t usually see these movies get right – the kid selling the DVDs, the soldiers listening to heavy metal and playing first-person shooters, the level of danger, some of the characterizations and some of the bomb setups.

But the role that the squad in The Hurt Locker plays is, at best, cobbled together from a bunch of unrelated units. A quick search of online forums or reviews where military personnel talk about the movie makes it clear pretty quickly, and it makes sense – bomb squad guys don’t go running off on their own to get in gunfights. They don’t engage in sniper duels with commando units. They don’t misbehave to the degree Sgt. James misbehaves and still get to keep their jobs. They shower. (That was one complaint that really struck me: in real life, Jeremy Rennick’s character definitely would have been better washed.) They aren’t some sort of red-wire cutting A-Team that gets to go wherever they want and shoot random people.

This may seem minor relative to the scope of the subject, but I think that sense is misguided. Everything about the movie is realistic, except what the characters do. This is a pretty low bar for realism—although I guess it’s sort of endemic of the War in Iraq; we know everything about it except what the people who are actually there are actually doing on an individual basis. To a degree, we aren’t invited by our media-driven and politically dominated hyper-reality to share their experiences.

But if all it takes to be a “realistic” movie is a “realistic” setting, and it’s not less realistic if the characters do absurd unrealistic things, then Lethal Weapon is just as realistic as The Hurt Locker, because there’s every indication that the Los Angeles they live in is a normal Los Angeles from 1987, and that the only really weird stuff happens to the characters in the movie.

By most accounts I’ve hunted down, The Hurt Locker isn’t as realistic as, say, Black Hawk Down, which also takes a lot of liberties with what happened when but at least arranges events somewhat plausibly, or as Jarhead, both of which do a better job of giving you a sense for what military personnel in specific jobs actually tend to do with their time (i.e., wait around a lot for other people in their huge organization to do stuff — not to go around all cowboy fixing the war themselves).

No, the difference is not realism. The difference I’m talking about here is legitimacy.

There’s another misconception out there — that The Hurt Locker isn’t a political film. The Hurt Locker is a tremendously political film. People’s senses have been dulled by too much Internet flamewar and cable news – being political doesn’t just mean taking a side and making shit up so you can rail at the other side’s cruel plot to destroy the world until you have an aneurism – it means looking to the consequences of what you say, do or portray on a given audience, and making choices based on what is likely to give you advantage with that group.

The board game version of Hostel.

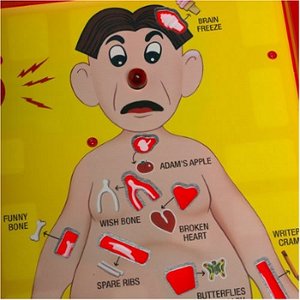

Being diplomatic in what you say is a big part of politics. And being centrist isn’t the same as having no position. The Hurt Locker is a delicate, careful, politically crafted movie. It plays Operation — grabbing as much bone as it can without touching the sides and setting off the red buzzer.

The Hurt Locker avoids the hot-button questions of whether the war in Iraq was justified or not precisely because it is being political. It is negotiating a place of legitimacy between the camps on the war, seeking a tone and a message that is not going to trip anybody’s yelling reflex and drive away half the potential audience for the movie.

So, you have a soldier who admits to the negative consequences of the war on his own humanity and ability to raise a child, and you see the war hurt Iraqi children, but then you see how much the U.S. soldier cares about Iraqi children and in many ways may be their only or best ally. But you also see him totally lost and incapable to doing anything to actually help, dropped in a foreign land as if by a cruel mistake. This movie is deftly political. It takes a whole bunch of stands, but it doesn’t stay on any one stand for too long, and since it doesn’t fall on the axis of rage, people with hair triggers attuned to one side or the other don’t see it taking any stands at all.

For legitimacy, your movie needs:

- A serious subject

- A meaningful message or set of messages

- Baseline quality and production values

- Not to be decried, demonized or marginalized by a major political coalition that serves as gatekeeper for such things

With the fourth being the biggest. Your movie is legitimate if the right people say it’s legitimate. No movie is Oscarworthy a priori.

Legitimate.

So, Dogma isn’t a legitimate movie because it has too many political detractors. It is “just” a Kevin Smith film (that is too sacrilegious for serious consideration). And Lethal Weapon isn’t legitimate because it has detractors – political blocs who require certain things that are arbitrary from the standpoint of moviemaking, but which are important to an individual or group political goal. Raiders of the Lost Ark is a legitimate movie, but Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom is not, because important political groups are uncomfortable with some of the things it says.

I should clarify – “politics” doesn’t just mean “electoral politics,” and “political groups” doesn’t just mean “Republicans vs. Democrats,” “Tories vs. Labor,” or “Berlusconi and the Mafia vs. Everybody Else and the Mafia.” As you discover in the working world (if you haven’t already, get ready, younger audience!), there is politics surrounding any resource or exchange of power – a discourse whose metadiscourse is about gaining advantage.

Illegitimate.

People choose to dislike Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom often because they benefit their own agendas by disliking it. But hey, maybe the concern is justified. Its portrayal of Hinduism is racist, or its use of children and heart-yoinking may be inappropriate. Justified or unjustified by our own beliefs (which are of course not all the same) these are still matters of influence and advantage, so they are still political. Politics and legitimacy really know little right or wrong.

Movies aren’t respected for “good” reasons. Just like human beings, they are respected, by and large, for “appropriate” reasons, with “appropriate” being termed by whomever is brokering power at the time.

So, despite being kind of an action movie, The Hurt Locker manages to weave through a complex political maze and arrive at legitimacy. This is something Lethal Weapon doesn’t even try to do.

A serious subject

This is my serious face.

Another way people might want to drive a wedge between The Hurt Locker and Lethal Weapon when confronted with the similarities — although imagining that there are all these people out there who would deem me legitimate enough to even argue with me about it is kind of hilarious — is that The Hurt Locker has a serious subject of international importance, and Lethal Weapon is “just entertainment.”

There are few words in criticism that irk me more than “just entertainment.” It’s “just for having fun.” It just causes people to miss so much about storytelling. If making a classic movie like Lethal Weapon just ain’t no thing and requires no art or technique to be admired, then let’s all do it and become millionaires! And besides, enjoying a movie, “just for entertainment” or no, involves engagement with the same sort of craft and fictive engineering. Good movies and bad movies have much more in common than they have by way of differences. I see little need to dismiss the finer points of comparison so readily. I also think I’ve written this paragraph too many times. Moving on.

Anyway, the potential objection — that Lethal Weapon doesn’t take on a serious subject — makes me chuckle whether or not it’s actually floating out there, because they actually made a Lethal Weapon movie about a serious subject of equal international importance to The Hurt Locker.

Lest we forget, Lethal Weapon 2 (the best Lethal Weapon and the first R rated movie I saw — my friend’s mom said we could rent it “As long as the R rating was for violence, not for sex,” and that made sense at the time) was about apartheid. Specifically, it was about dealing with the obstructive legal legitimacy of the white South African apartheid government while condemning it on moral grounds for its evils and injustice. Of course, Lethal Weapon 2 explores its serious subject through slightly different kinds of scenes, like this one, which is legendary (they’re trying to infiltrate the South African consulate by creating a diversion):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zje1ny0F_js

A lot of the movie builds the narrative around the concept of diplomatic immunity, which stands in for Kissinger-esque legitimacy as a moral problem of the relationships between countries (There I go! Stepping on Sheely’s turf! Take it to the comments, folks!). At any rate, the matter is settled, well, with directness and expediency, if not due process:

Obviously, this is the politics of a much more certain and resolved auteur, who takes a clearer, and perhaps less practical stand on a less morally ambiguous issue. But you can’t blame it for lack of a serious subject … even though you can probably blame it for what it does with that subject. Which, in case YouTube took down the clip, is to shoot it in the head while saying “It’s just been revoked!”

But, holding back from that for a moment – is what Lethal Weapon does with apartheid really so bad? Is the problem with the dishonesty surrounding the War in Iraq the inherent dishonesty of propaganda and its use by leadership, or is it just how it was used this time around? Were that self-same reductionism used in service of a less morally ambiguous purpose – or one on which there was broader enduring consensus – or heck, one that led to quicker success, would it still be such a bad thing?

That’s for a future post, and for the comments. I’m not touching that here. I’m getting too old for that shit.

Filmic craft

I’ll go through this quickly:

Getting crafty.

The script for The Hurt Locker is solid, but it’s nothing spectacular. It’s episodic, and very little holds the episodes together. The characters are written a bit flat and erratic, but that makes sense, because this is an action movie. It has an uneasy relationship with plausibility that betrays that it was written by an embedded journalist – our culture’s fishmonger of hyper-real wartime fantasy passed off as truth. The dialogue is kind of cliché a lot of the time. The framing devices are a bit clunky.

(By the way, I’ve used the term hyper-reality a lot in this post — I’m perhaps abusing the term a bit. It’s a post-modernish word that refers to a case where people live in a fictional world that to themselves is indistinguishable from being real. So, if somebody really feels like their Second Life character is the real them, that’s hyper-reality. I comment fairly frequently on this website and in the podcast that the world that the maelstrom of media and news creates for us around any current event is a hyper-reality — it is refracted through such a thick lens of perspective and reimagining that, while we consider it to be real, it’s actually a fiction. We experience the war in Iraq we are told about and imagine is happening, not the one actually happening, which is so complex, so far away, and so divorced from many of our own experiences that we cannot begin to comprehend what it means in a human sense.)

Lethal Weapon has a very silly script, but it succeeds very well at what it’s trying to do. So, The Hurt Locker has an advantage in writing, but not an insurmountable one.

The Hurt Locker looks really really good. It has very high production values. It employs all sorts of techniques that didn’t even exist in 1987. This is where comparing new movies to old movies is like comparing today’s chessmasters to chessmasters from a hundred years ago – today’s chessmasters have the advantage of working on their predecessors’ shoulders – and of reading all their games. So, The Hurt Locker is miles ahead of Lethal Weapon in most technical categories – but the basic blocking is pretty much the same. The mise en scene for the actors isn’t that much more advanced – it’s everything else that’s advanced.

It also sounds really good. As I’ve mentioned before, the sountrack for Lethal Weapon is totally 80s and really really silly – it’s the chief thing that makes the movie seem “cheaper” than rough contemporaries like Terminator and Die Hard. That and the terrible, terrible ensemble acting. Observe:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dUlfNMTc6Xc

The lead acting – and here’s where I have to put my foot down – the lead acting in Lethal Weapon is better than the acting in The Hurt Locker. It’s a slightly different set of techniques, but it’s just as complex, if not moreso, and shows a broader command of the art and a greater capacity for affect (ring up Colley Cibber and call me a Sentimentalist).

Is it fair for Jeremy Renner to win an Oscar for his role, when so many actors have done so much for the “loose cannon” cop/soldier over the years and received little but derision for it? Well, that and lots and lots of money — so again, I guess it’s fine. Laughing, bank, etc.

Nothing against Renner’s performance – it’s great, he’s great. But Mel Gibson was better, even when he was being silly (and often because he was being silly – stepping through the hyperreality and admitting that the situations are absurd is important to understanding how these sorts of characters work). This is the kind of role that makes you marvel at people like Mel Gibson, Tom Cruise, Bruce Willis or Wesley Snipes – there’s a lot not to like about guys like this, but they can act the shit out of action movie characters. And Sgt. James is an action movie character. Renner does a great job, but Gibson does better with sloppier, more challenging material. Old Mel Gibson is just so much fun to watch.

Of course, that’s not entirely fair; their performance styles are really different, and the tone they strike is pretty different most of the time. Mel Gibson probably can’t do what Renner does as well as Renner does it — and a lot of my friends might chastise me for underrating the importance of an actor making subtle but present onscreen choices. But I think it’s important to point out that the comparisons based on film-making and its related crafts are not entirely one-sided here.

And, lest it be forgotten, Danny Glover is an amazing, amazing performer. He’s got to be one of the best overall actors of his generation. Back in 1987, Danny Glover was the same as he is now — one of those rare actors who effortlessly moves between excelling in popcorn action movies, serious films, and the Broadway stage. The same year he played Murtaugh for the first time, he played Nelson Mandela on TV. If there’s any ancillary benefit to this post, let it be the reminder that Danny Glover really is that awesome. That’s probably what this section is all about, actually. An excuse for writing that.

The next section will be more important and more interesting, I promise.

I’m glad to have read this before Oscars night. Now, I no longer have to root for this movie to destroy Avatar. Now, I am completely indifferent to the whole process, much like my views on politics! fenzel, you’ve saved me from caring, which in its own way is one of the greatest gifts imaginable.

Addendum to your post- that staff psychologist, you know the one… he’s the same head shrink character from Lethal Weapon! They have a psychologist following around the team in both movies, for crying out loud!

Wow, this is weird. Carlos had this exact idea for an OTI piece but never got around to writing it. I guess The Hurt Locker really IS Lethal Weapon! (This is also how my dad refers to this movie.)

Also: While I wouldn’t say The Hurt Locker is a bad film, it clearly doesn’t deserve all the praise it’s getting. There. I said it so you don’t have to.

It is interesting to see the difference in the way Hollywood deals with madness. It seems that too often they take the view that one needs to just talk about it with a friend and suddenly its all betters. Having several good friends with some mental health problems, I can tell you that constant anxiety or depression don’t just go away because you get hugs. Sure, it helps, but I think since Lethal Weapon, people have come to recognize that there a physical nature for our moods and personalities, namely the neurotransmitters zooming around in our heads, sometimes developing in ways that aren’t our fault. I felt like some movies like Girl, Interrupted were shouting at some people to not be so sad all the time, to just suck it up, talk it out, and get over it. But can there really be mind over matter, when you mind fundamentally IS matter?

@mlawski and @fenzel: I think The Hurt Locker is getting all the praise it deserves. Possibly it deserves more. And yet I agree with Fenzel’s ultimate take – that by presenting the elements of a buddy cop film in a stylized, minimalist and serious way, The Hurt Locker gets more respect than earlier movies that have tread the same ground.

One could make the same case about several other critical darlings – No Country For Old Men vs. blaxploitation cinema, or There Will Be Blood vs. Dallas.

I think we can fill out the account of why “just entertainment” is such a crock, though this particular line of inquiry is not really germane to the point you’re trying to make. Not directly, anyway.

Even more often than it’s deployed by critics or diletantes to dismiss something they deem unworthy of consideration, it’s deployed by normal viewers (that is to say, viewers without any skin in the art-making game) to excuse the guilt they feel for preferring movies that aren’t preachy or generally considered “good for you.”

I think it’s a tragedy that we have to apologize for our pleasures, especially when the pleasure in question is a good story well told.

Just lost my comment to the void, but here’s the short version:

The Hurt Locker is clearly a well-made movie, and my problems with it are somewhat personal. I’m just over this type of character — see my comments on Stokes’s Overthinking Cowboy Bebop articles to see how much I want to slap Spike Spiegel across the face. At the risk of sounding political, the Renner character is so typically “American” — ooh, manly-man rugged individualist who is SO GOOD at his job that he can get away with being an asshole sociopath who gets everyone around him killed because he’s too much of a Real Man to work with others or seek psychological help to get over his death wish. It wouldn’t bother me so much if these types of characters weren’t always presented as super-cool anti-heroes instead of the nutjobs they so obviously are. It’s an action-adventure fantasy, that’s all.

Also(and maybe I shouldn’t get into this argument again), although I love many things that fall into the “just entertainment” category, can’t we agree at a certain point that Macbeth is better in some ways than Die Hard? (For the record, I love Die Hard, and I think Macbeth is incredibly entertaining.) Or, on the TV front, can’t we all agree that The Wire, which is both entertaining and “Important,” is in some ways superior to the best episodes of Burn Notice, which are incredibly entertaining but the polar opposite of “Important”?

@shana,

Well, MacBeth is just a script. Die Hard is a whole production. So you’d have to judge an entire production of MacBeth against Die Hard. I’ve seen a couple of movie and live productions of MacBeth, and while the script is better than the Die Hard script for a bunch of reasons, the productions were generally not as good as Die Hard.

I would say that if you want to point to the Wire being better than Burn Notice, you could find justifiable reasons to claim it, but I would caution against relying on its “importance.” The Wire does a lot of awesome things other than just be “important.” It isn’t just a bad history of Baltimore – it has a lot of artistry. Now, I haven’t seen Burn Notice, so I can’t make comparisons there, but I could do a pretty detailed comparison of The Wire and The Sheild that didn’t include at all whether one show was more “important” than the other.

I think using legitimacy or seriousness as the main criteria for quality is reductive. You don’t have to rely on it. Shakespeare certainly didn’t — his plays are funny, his characters are compelling and vivacious, and he’s not above telling dirty jokes. He didn’t have the luxury of patting himself on the back for being important, because Shakespeare made art people actually watched for a living and didn’t rely on criticial approval for his professional reward and fulfillment.

Maybe this comes from reading English literary criticism from over the centuries — watching a particular poet fall in and out of favor based on the intellectual fashion of the time. So much of the approval or legitimacy of the academy (or Academy, ‘natch) is just fashion — what people happen to think is important, what advances their own goals for themselves and their art form.

So, no, I’m not willing to concede that, say, Pilgrim’s Progress is better than Harold and Kumar go to White Castle, just because one of them is Worthy and Important the other one is contemporary, market-driven popular entertainment.

I agree with you on The Hurt Locker, by the way. The original article had a few more paragraphs bashing it, but they weren’t well thought out or necessary, and they were too relative to be worth pubilshing. The Hurt Locker is a very good movie that deserves praise, it’s more a matter of whether it deserves as much praise as it is getting or not — and at that point that’s kind of irrelevant; we have to see whether it wins the big Oscars or not, because I’m not sure everybody is on the same page about how much this movie is actually being praised. A lot of that is speculation about buzz. So, we’ll see how it turns out in the end.

@fenzel and the rest: Your comment makes a lot of sense. The fact is, I keep going back and forth on the “how do we judge art?” question. I’ve spent many hours of my life arguing that, yes, Jack Black’s Year One is just as much “art” as Hamlet. Art criticism is probably more subjective than any field on Earth, so it’s easy to make these kinds of arguments.

But I still don’t know. Part of me really wants to say, “Yes, definitively, 12 Angry Men is superior to The Blind Side, and anyone who disagrees is a big stupid.” And it’s not just because 12 Angry Men has superior acting or a tighter script — it’s because 12 Angry Men is ABOUT something and The Blind Side is just a series of Lifetime movie cliches. Why should movies be about something? I’m not saying that they have to be heavy-handed and preachy. I’m just saying that maybe those films that actually illuminate a truth about our real, lived lives are automatically a step up from films that operate in fantasy Hollywood-land. (And, no, this isn’t about genre: a piece of fantasy fiction like Pan’s Labyrinth can be considered more “true to life” than a theoretically “realistic” film like Valentine’s Day.)

Another problem with Macbeth: No Alan Rickman. Although Alan Rickman playing Macbeth in a movie version is definitely something I could get behind.

I think separating these two is more than just contextualizing. I don’t actually believe that “war is a drug” is a major thesis point of the film , I think its about much more than that, but that’s not what the topic is about so I’ll skip it.

Something my room mate mentioned was that the big thing for the Hurt Locker can be viewed through O’Brian’s The Things They Carried; which is not exactly entirely accurate about Vietnam, but is a metaphor that conveys the experiential truth of that conflict, the Hurt Locker is very similar. It shows a metaphor inside a certain context; whereas Lethal Weapon is a specific story entailing certain features. The Hurt Locker is too, to a certain degree but the difference my room mate discerned is that Lethal Weapon’s story is intrinsic whereas the Hurt Locker’s episodic nature was inherent not to describing the story but to describing certain features about the characters and the conflict. The Lethal Weapon is specifically structural whereas the Hurt Locker is more deconstructionist.

I think what separates The Hurt Locker from something like Generation Kill (the series form a book literally based on true events from the onset of the war) is that while the prior is hyper-realistic and the other is just realistic (because it is very close to the original source material just off form the actual events) is that the metaphor in the Hurt Locker is to convey an idea but that Generation Kill is to convey something that occurred and to show the “truth” in that thing, rather than the “idea” of Hurt Locker.

You’ve said a lot of interesting things here but ultimately I don’t think the similarity argument works. For me the part where the comparison really breaks down is this: Riggs is the classic Broken Hero, who’s aberrant behavior stems from some damage in his past, usually a loss, sometimes coupled with previously questionable behavior of his own. A Broken Hero is ultimately saved/redeemed by connection to a person or people around him. James’s aberrant behavior and his damage are pretty much one and the same and it’s made quite clear that any connections he might have to other people in his life are not going to make any difference.