Grand Theft Auto III did not invent the notion of “sandbox play” by any stretch. 8-bit predecessors like the space exploration game Elite (which inspired EVE Online) created random universes for your protagonist to explore. SimCity, despite several competitive scenarios with defined end points, was structured around open, unlimited play. And Shadowrun for the SEGA Genesis gave you the chance to go on randomly generated missions for underworld employers – a sneak peek of the “quest” structure that would define MMORPGs a decade later.

But the incredible success of GTA III forced the industry to take notice. GTA III opened up the genre of sandbox games for the video game console. Dozens of imitators, and a few innovators, followed.

Start ... spreadin' the news!

Sandbox games all followed a similar trend, setting you on a path and then cutting you loose after a few tentative steps. You don’t need to uncover why the Emperor ordered your release from prison in The Elder Scrolls: Morrowind if you don’t want to. As soon as you’re off the boat in Seyda Neen, you can start learning spells, robbing tourists or slaying mud crabs right away. GTA: Vice City let you accumulate wealth and property, setting up illegal income streams to fund your cars, houses and threads.

Even if a sandbox game rejects the single-goal storyline, it’s only as good as the other goals it offers. Even if you don’t want to save the world, you still need some carrot in front of you: a mansion in the city; the head office at the Fighter’s Guild; an interstellar trading corporation with your name on it. This is because humans need goals. A game with no goals inherent, merely opportunities to explore and obstacles to overcome, probably wouldn’t sell very well.

Games have reverted from the categorical imperative (where gameplay could always be willed into a universal law) to the hypothetical imperative. If you want this, do that. If you want a house in the city, get $100,000 and permission from the Mayor. If you want to run your own criminal empire, assassinate the current boss. If you want to slay a dragon, get a set of ceramic armor and a unique glowing sword.

The game may only offer a few paths to what you want. But the game no longer tells you what to want.

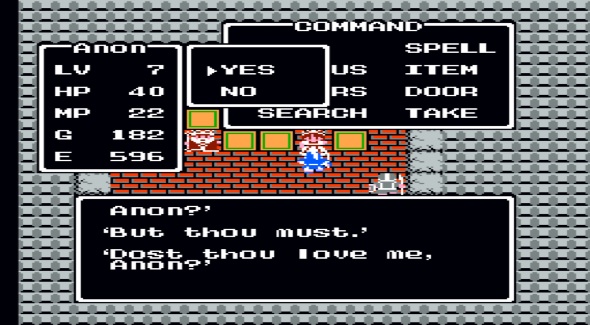

You can live a full life and never run into this guy, for instance.

The deontological ethics of Immanuel Kant arose as a response to the hypothetical imperatives in philosophy at the time. If you want to be saved, you must have faith and good works (Protestantism). If you want to be a good citizen, be a productive and honest member of the community (Plato’s Republic). If you want x, then the right action – the moral choice – is y. But still debate raged on the question of What Humans Should Want. Kant changed the game by changing the question. He didn’t ask what means we should pursue to which ends, but whether the means/ends question was even being asked in the right way.

No one would assert that sandbox games are necessarily superior to linear games. Both have their advantages. Sandbox games feel more like real life because of the ability to choose between goals. Linear games are less likely to flounder in unsatisfying shallows. But the debate over the merits of sandbox play vs. linear play is not a revolutionary one. It’s the same debate philosophers have been having for the past two hundred years.

We know how that debate’s turned out. While deontological ethics still have a few academic defenders – Frances Kamm most famous among them – their opponents outnumber them like a swarm. Even people who don’t follow philosophical journals recognize the names of teleological (or consequentialist) ethicists: Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, John Harsanyi, Amartya Sen, Robert Nozick, etc, etc. The consensus is clear: philosophers prefer to judge actions by their consequences, rather than fitting them to a universal maxim.

Robert Nozick beat Contra without losing a life.

And now that sandbox play has been discovered, the video game market seems to be heading that way. The ability to pursue different goals, combined with the flexibility of user-generated gameplay, has made MMORPGs rich and satisfying. Many World of Warcraft players enjoy the game by focusing on crafting, or finding unique items to sell at the Auction House. And the Guild structure – which exists almost entirely in message boards and private chats, only providing the loosest of structures in the game – is a perfect example of players making their own goals. No town guard in Azeroth will recognize you if you’re the head of your Guild, but that doesn’t stop people from trying.

But Kant’s big contribution to philosophy wasn’t deontological ethics. It was asking a question that changed the debate. When it comes to video games, who’s asking that question?

Amazing article.

Would entering the Konami Code to start with 30 lives be a violation of Kant’s second maxim?

This is great stuff, and I think you only scratch the surface.

I think what a lot of videogames do is strive to give you the ILLUSION of control, of being free to explore the world, but actually limiting your choices as strictly as Mario. Grand Theft Auto is a pretty good example. Yes, you can wander around Liberty City all you want… but you can’t enter 99% of the buildings. You can take on taxi missions, buy new clothes, and find all of those hidden pigeons. But those are side quests and mini-games. They don’t make the game open-ended. The game only has one ending, and there’s only one way to get there.

If the Grand Theft Auto games are “sandbox” games, than isn’t Final Fantasy 1 a “sandbox” game?

Other games offer you real choices, but choices that are basically meaningless. Take Bioshock – you can either harvest Little Sisters, or free them. But either way, you get pretty good rewards, so it doesn’t really change the game. A bunch of games let you choose between a “good” and “evil” path (Infamous, Dante’s Inferno, a bunch of Star Wars games, etc). But usually, all this does is determine what special abilities you gain, and which cutscene you get at the end.

@Rob: it’d take a better Kantian than myself to answer, but I’d say no, unless you count each life as a discrete “person.”

@Belinkie: I never beat GTA III, but I have completed the main storyline of GTA: Vice City. You kill all the mobsters sent against you in your palatial mansion. And the game keeps going. You don’t stop playing at that point. GTA: Vice City never “ends” in the sense that other games end (at least, not in my experience). So if you complete the “official” storyline, you can now live out your life as a successful mob boss.

@perich – It’s true that Vice City doesn’t actually stop you from playing, after the ending. But I really don’t see why you’d keep playing. Sure, you could run around trying to get five stars, or find all the rare cars. But I still say the large majority of the fun in that game is tied into the storyline. (Obviously, I’m not one of those guys who tries to get all the XBox “achievements”.)

I think what we need is a Sandbox Scale. Game which are strictly linear are on one side. For instance (to name two of my favorites), Left 4 Dead and Modern Warfare. You proceed from the beginning of the level to the end of the level. There are no detours to take. (Ignore the multiplayer modes, for now.)

Grand Theft Auto (the whole series) is in the middle of that scale. You character has clear goals, a series of missions, and a predetermined ending (or two). But there are a lot of valid ways to enjoy the game outside of these goals. Here’s the key thing for me: just because Grand Theft Auto has a bunch of street races you can participate in doesn’t make racing on equal footing to all the plot-related missions. Racing is clearly a minor part of the game.

So what are the most sandboxy of all games? Discounting the experimental indie games? Maybe World of Warcraft – I like that example. Obviously, you can’t do ANYTHING you want, but gameplay is a lot more freeform than Grand Theft Auto, which offers you a clear path you have to choose to AVOID.

@Belinkie: this may be personal taste, but I don’t see the storyline quest in Vice City as being any different from the main Alliance or Horde quests in World of Warcraft.

But I like the idea of a scale of linearity from 1 to 10, where 1 = most linear and 10 = most open (without being “reality itself”). I’ll offer my own scale.

1 = Kung Fu

2 = Super Mario Bros.

3 = Mega Man II / Ducktales

4 = Bubble Bobble

5 = Pokemon

6 = Animal Crossing

7 = GTA / Elder Scrolls

8 = World of Warcraft / EVE Online

9 = SimCity

10 = Second Life

Excellent article, thanks!

@Perich – Makes sense. If we believe that a Contra is reincarnated for each of his 3 lives (or 30), and that he is the same man as long as he has a character in play, then I guess entering the Konami code is in fact a categorical imperative. And even if we believe that the different lives of a Contra represent different individuals, all these soldiers have the same duty. The survival of humanity is at stake, regardless of whether it takes 3 soldiers or 30…

(Now I’m reminded of a short story that Belinkie wrote many years ago, a story titled “Red Pants, Blue Pants”, which was the first and only previous time I’ve been led to contemplate the free will of video game characters. I don’t remember whether Belinkie referenced the Konami code though…)

@Rob – Wowzers. It has been a LONG time since I’ve thought about Red Pants/Blue Pants.

I’m in the midst of my second playthrough of Mass Effect 2, and I’m struck by how well the game provides the illusion that every decision made will have far-reaching implications and opportunities for greater branching of the plot and subplots. The good/evil (or paragon/renegade) mechanic, paying off plot points and decisions made in the first installment, and the seemingly open-world structure all provide granularity to your “good” or “bad” ending — and even a “bad” ending is embraced as a possible outcome to be carried over to the final chapter in the trilogy.

Everyone I’ve discussed ME2 with has had a very different experience with the game, and that speaks to how well-crafted it and other good open-world/sandbox games are. Every game is a series of segments, even the sandboxy ones, where the meaty missions are suspended in a malleable goo where you’re given the illusion of being able to go where you want and do as you please (within the rules and conceits of the game). When you think about it, even though Super Mario Bros. lacks these interstitial playgrounds, there are still hundreds of ways to play the game. You could jump in one place until time runs out, and that’s a complete game of Mario. What excites me most is that video games are beginning to let us dance with a game or fight with it. To finally embrace all of the ways of playing.

apologies for being semi off topic – great read, perich.

I heart Perich more than I heart Mario!

This is a little OT, but:

When people talk about video games as “art,” I think the paradigm most people think of is a painting, or a novel. You enter into the author’s world, explore its confines, and reach the end. But what if the proper metaphor is in fact a piece of written music? There is a “Beethoven’s 9th Symphony,” for example, but there is not authoritative performance of it. In order to experience the piece as it was meant to be experienced, you need to make choices about the performance of it, either directly (as part of an orchestra) or indirectly (by choosing to listen to a particular performance and/or recording).

Video games, then, can be the same way: the skeleton is there, but you – as player/performer – choose how to interpret the work. Do you play through it in a manic weekend? An hour at a time? Do you explore the side quests? Do you choose “good” vs. “evil” actions in those games that let you? The experience is still bounded by the programming of the game (or the score, in written music), but you choose how you experience it.

Maybe the phrase to “play” a video game now has more meaning than it did when it was first used?

Who would ever forget about Mario? It’s the game we grew up playing with. Since it’s still hitting the market until the present, it can now be tagged as the video game of all time, right?

GREAT article, but what was up with that Mega Man 2 video? Downright average playing there.

One of the guys from The Megas did a really great complete-game speedrun and they did commentary on it:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rx7Y14sJluU

(the Air Man section section starts about 3:12.

Since when are consequentialists a majority amongst philosophers? According to the PhilPapers, a recent survey of actual philosophers, they are split evenly between deontological ethics, virtue ethics (itself often considered a form of deontological ethics) and consequentialism. If anything, the secular trend favors virtue ethics.

Fascinating read, Perich. Though a couple line struck me in particular:

But the first generations of video games all had to end at the same place: our hero, standing over the defeated final boss, having rescued the princess, acquired the MacGuffin or saved the world.

and

A game with no goals inherent, merely opportunities to explore and obstacles to overcome, probably wouldn’t sell very well.

Many of the earlier video games, especially those that became popular in the late 70s/80s, followed the latter’s exact structure, with no real hero at all. Take Asteroids. What is the only function of the ship in Asteroids? To destroy asteroids. What is the result of the ship destroying asteroids? More asteroids appear. The cycle never ends, and there is no ultimate end goal, no final asteroid-boss that the ship must defeat. Sure, the player might aim for the high score, or try to complete several dozen levels without dying, but that calls back to your earlier point: the asteroid world does not give a shit, and will continue lobbing rocks at your tiny-ass ship until you die. And yet, this game was still able to drain the wallets of adolescents back when arcades were popular. I sort of feel like the philosophical response to that would be akin to a working stiff saying, “Who cares what Kant or Mill has to say? That doesn’t really change the fact I have to go to my job every day.” Any number of popular single-player puzzle video games also follows this same basic structure and perform really well within the cell phone market.

Do you have any additional thoughts on Second Life? I don’t know too much about it (since I need my goals, or at least obstacles), but from what I do know about it, the openness of the system provides a Calvinball-esque opportunity to create and pursue whatever arbitrary goals you decide in a gigantic exercise of existentialism.

@Joshua Lyle: really! I stand corrected. The article reflects my own bias – I’ve heard of more consequentialists than I have deontologists, so I just assumed they were more numerous. Good cite!

@Tom: you ought to read this. Actually, everyone should – one of the best overthought pieces on video games I’ve ever come across.