King of the World.

Recently, Fenzel spelled out Five Reasons Why Avatar Will Suck. I want to add one more. Every article that I’ve read about the movie waxes poetic about how Cameron has been given carte blanche to pursue his vision. He’s spent almost four years in production, and more than 300 million dollars. He even invented his own camera. This is a man with unlimited resources and total creative control. That makes me very nervous.

This may seem like a strange thing to say. Don’t we all agree that in a perfect world, all artists should have unfettered freedom? You don’t want gallery owners telling Picasso how to paint, or concert hall owners telling Mozart how to compose. And when it comes to artsy filmmakers, I completely agree. By all means, write Paul Thomas Anderson a blank check and leave him the hell alone.

But while Avatar is certainly art, it’s entertainment first and foremost. It’s a blockbuster, the most tricky of all genres to nail. Every year, there’s a handful of amazing dramas and hilarious comedies. But making a movie like Independence Day is subtle pop culture alchemy. How many awesome blockbusters has 2009 given us? I’d argue Star Trek, and that’s it. (And while Star Trek was fun, I don’t think it’s on the same level as The Dark Knight.)

Can't get his pet project funded. I'm not kidding.

To make a good blockbuster, you need a great director. Then you need to give him enough power to bring his vision to life. But there need to be checks and balances. A blockbuster is a populist creature – the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the director. The best blockbusters absolutely end up capturing the worldview of their creators… but that’s not their purpose. Good blockbusters are never self-indulgent; they are audience-indulgent.

To understand why Avatar worries me, you have to understand how rare Cameron’s level of absolute, godlike, no-questions-asked control is. For instance, many people assume that Steven Spielberg can go out and make any movie he wants. But back in February, The Big Money reported that he couldn’t find anyone to fund a Lincoln biopic he’s been cooking up.

Think about that: Steven Spielberg simply cannot get his movie off the ground. And it’s not a fluke thing.

The most recent issue of Esquire reports on Ryan Kavanaugh, a 34-year-old venture capitalist whose company is funding about 35 movies in 2010. The article begins with director Ron Howard waiting outside the guy’s office to ask for money. Just because Frost/Nixon was a success does not mean that people are rushing to finance Howard’s next project. Even for A-list directors, getting a movie greenlit can be tricky. Getting a massive blockbuster greenlit is even harder.

And even when they get the go-ahead, it doesn’t mean they call all the shots. They have limited budgets. They have producers calling in daily to discuss the rushes. They have demanding stars with massive egos.

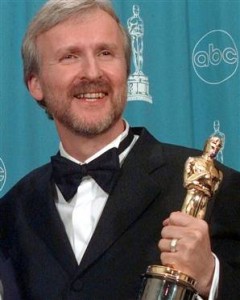

James Cameron has been a pretty powerful guy for his whole career, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t had to deal with nervous and demanding studio executives. His battles with Fox during the Titanic shoot are legendary – at one point, he gave up his own salary to keep production going.

But as he himself memorably put it, Titanic’s success made him King of the World. I can only think of a few cases in recent history where a director had this kind of clout… and they didn’t end well.

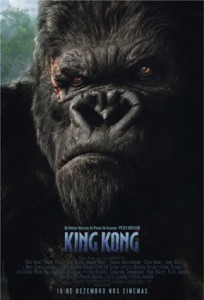

CASE STUDY: King Kong

CASE STUDY: King Kong

After co-writing, directing, producing, and running the special effects company for the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Peter Jackson had a Cameron-level of mojo working in 2003. And like Cameron, he had a dream project that had been gestating for years. Jackson had actually shopped around a script for King Kong in 1996, which had the misfortune of landing on everyone’s desks right after Godzilla bombed at the box office. After the epic success of Rings, it didn’t surprise anyone that he signed a deal to make Kong (which made him the highest-paid director in Hollywood history).

I don’t want to suggest that King Kong is a terrible movie. I like it. If it were on right now, I’d say, “Ooh, King Kong. I like that movie.” But the movie is three hours and seven minutes. That’s almost twice the length of the original, which shares virtually the same plot. This isn’t an epic like Lord of the Rings that needs that kind of sprawl; it’s a simple, straightforward adventure movie. Three hours is too long, no matter how good each individual scene is.

We don’t even see Kong for seventy minutes. Those of you who know about the Ghost Ship Moment understand that this concerns me.

I think it’s a fair assumption that if it had been any other director besides Jackson, the studio would have insisted on a more bladder-friendly running time, and they would have been right. And the New York Times reported that in the end, Peter Jackson put up millions of his own money to cover the additional expense. You die-hard King Kong fans can argue with me, but I think all he did was buy enough expensive celluloid rope to hang himself with. The movie would have been better off shorter.

But even putting aside the running time, I’d argue that Peter Jackson could have done better with a little more studio pressure… because I’ve read the 1996 King Kong script. It’s available online here, and I think it’s better.

Quickly: how does the 2005 King Kong begin? Can you remember? Well, the 1996 script begins with a sensational dogfighting sequence set in World War I, introducing Jack Driscoll (the Adrian Brody character) as a young pilot. The scene does more than start the movie off with a bang – it establishes a couple important things about Driscoll’s character. And more importantly, it establishes he can fly a plane, because in the final reel, he steals an aircraft to try and protect Kong. In the 2005 Kong, Adrian Brody barely has anything to do in the last third of the movie. Having him jump in a plane seems much more satisfying. It also gives Ann Darrow a reason to take him back; he redeems himself for his part in Kong’s capture.

In a lot of different ways, the 1996 screenplay just works better. For instance, in the 2005 version, it is never made clear how the film producer (Jack Black) gets his hands on a map to Skull Island. He just shows up in his first scene waving it around. This is kind of a huge plot hole. And even if you buy this, why exactly is he looking for this uncharted island anyway? All he needs is a jungle to film an adventure screenplay he already has. The whole journey seems forced.

In the 1996 screenplay, the producer isn’t trying to make an adventure story – he’s a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not-style documentarian, hacking his way through jungles in search of beautiful bare-breasted natives he can film, always putting himself front and center. In this version, it makes perfect sense that he’s trying to find this mysterious island – that’s what he does. (Ann, by the way, isn’t an actress. She’s the daughter of a famous archeologist that Denham ripped off.)

The 1996 screenplay is faster, tighter, and more fun. No pointless monologues about Heart of Darkness. This was before Jackson had been nominated for an Oscar, and he wasn’t taking himself too seriously. More importantly, when Jackson sat down to write the 2003 screenplay, he knew it was getting made. He didn’t have to please anyone but himself. He’s a talented guy, and King Kong still has a lot going for it. Sadly, I can’t say as much for…

The same is true with music, too. Once someone gets big enough that they live in a bubble world where no one can tell them no, they end up producing some horrible, often overproduced junk. Michael Jackson circa Dangerous is the most obvious example, but I’m sure we could very easily come up with a bunch of others.

Another case of directors gone wild with all their favourite toys is the Wachowski Brothers in The Matrix. The first film was ‘tamed’ by the fact they had to prove themselves – they did, and created a fantastic universe and a viable megabucks franchise. Which they ruined with Matrix 2 & 3 – simply because they had so many toys and so much power they forgot to stick to a compelling storyline.

This is the reason that whatever Joss Whedon makes will always be at least a little bit good; even when the executives work WITH him, they are against him. Even if you’re not a hardcore Whedonite, I bet you’d prefer a bad episode of Dollhouse over the Village any day.

Interesting you bring up LADY IN THE WATER — I *whole-heartedly* recommend the book “The Man Who Heard Voices” by Michael Bamberger (of which the EW article may have been an excerpt, if I recall). It’s an absolutely fascinating look at Shyamalan as he developed and made the movie, and the aftermath. Some brilliant stories, all of which are better than the ones in the EW piece… like sending his assistant with the script to hand-deliver to the head of Disney on a weekend, then fuming when he found out the studio head had taken her young daughter to a birthday party.

Pick it up for Christmas. An excellent look at the hubris of a once-charmed Hollywood director.

@Kevin – I am very curious about this book. On the one hand, it seems like the book was all Shyamalan’s idea – he INVITED this writer to watch his process, and presumably the primary source for the whole thing is Shyamalan himself. So this is part of his relentless self-promotion, down to the smug subtitle (“How M. Night Shyamalan Risked His Career on a Fairy Tale,” as if he’s some sort of hero).

On the other hand, it seems like every single page makes Night out to be the worst person in the universe, a raving egomaniac whose sense of entitlement knows no bounds. (Keep in mind, the movie was a complete bomb and a critical failure. This isn’t the story of how Coppola made Apocolypse Now against all odds.)

So I guess my question is, do you think that Shymalan feels burned by the way the writer portrayed him? Or is the book exactly what he wanted, and he is SO CAUGHT IN THE BUBBLE that he actually doesn’t realize how his behavior seems to normal people? Does Shymalan wish the book had never been published, or is it his very favorite book ever?

Almodovar, Bergman and any number of non-English-language directors had huge amounts of financial and artistic freedom and never made nonsensical vanity projects. Could it be that this syndrome has less to do with freedom than it has to do with commerce-oriented filmmaking in general?

If your career depends more on your ability to bring in revenue than on artistic achievement, of course you’re going to spend $300 million dollars on a project if you have that opportunity. The more money is spent on the project, the more the studio gets behind marketing the final product and the more eventual box office.

I think that this uber-narrative of the heroic artist who crumbles under his own hubris ignores the economic reality of the movie business. The studios wouldn’t care if every movie were 90 minutes of George Clooney running around in nippley black rubber, so long as people bought tickets. And in the end, quality has nothing to do with box office. The Phantom Menace made a lot of money. Nearly $1 billion worldwide.

Filmmakers get exactly as much creative control as they earn in the marketplace. When they fail to maintain that economic success, the control vanishes. Which makes sense, since the people who greenlight movies have no idea what people want to see. They have to trust people who have proven their capacity to produce valuable commodities.

Anyway, my point is that you should blame the cynical studio heads for producing movies they wouldn’t watch, not the directors who take the huge risk to try to create something they care about.

Interesting. What you actually want for non-blockbuster movies is to give every artist complete creative control and a low budget. This will prove that complete creative control generally gives terrible movies, but that doesn’t matter, because 1 in every 100 will be fantastic, and the only one we ever hear of – the Clerks, El Mariachi, Blair Witch, Paranormal Activity etc.

The mistake Hollywood makes is one that we are warned against in financial products – past performance is not an indication of future performance. No-one knows why that first film was a success, perhaps it was a fluke. Even if they have stumbled across a talented director who could churn out a bunch of these movies, they then make the “fundamental attribution error” – believing that the ability to do so in a small budget context translates to the ability to do it with a large budget (hello Kevin Smith!).

This poses a dilemma for the studio trying to find a successful blockbuster. There is so much money involved, that they will be risk averse and make a safe movie – witness almost every blockbuster of the last 10 years. If what they want is the mega-success, they can’t play safe, but need to adopt the mindset of the “small budget ecosystem” where some big budget films with creative control fail, and the odd one succeeds beyond expectation. The difference with big budgets is that we notice the failures as well as the successes – i.e. we have a cognitive bias in the small budget films, corrected in the big budget market.

What this means is that I applaud the studios willing to take this risk, even if it does lead to Waterworld, Avatar etc, because 1 in every 10 will be THE film. Otherwise our alternative is a world of McGs churning out safe blockbusters designed by focus group. This is why private equity is an interesting model for film makers. They can take this portfolio approach, and even create funds with appropriate risk profiles – “indie film” – risky, “rom com film” – safe, “safe blockbuster” – moderately risky, “creative control blockbuster” – highly risky. This takes the risk decision away from studio execs who have a naturally risk averse attitude due to the potential loss of their jobs. Explicit risk profiling will alter the expectation level placed on them.

Yours, looking forward to investing in IndieFund soon,

Chris

@callot

I can’t really get behind the idea that publicly funded international filmmakers never make nonsensical vanity projects. Relative to the expectations of a mainstream audience, they make more nonsensical vanity projects than anybody else – they are just held to different standards and are not as publicly flayed when their projects come up just short of spec. As Matt wrote in his article, when art rather than entertainment is the goal in itself, this whole discussion of vanity and pleasing the audience is kind of moot.

But more seriously, I think it’s a matter of selection bias – it’s easy to praise bergman, especially to people who have maybe seen a few of his movies. But would the Cremaster Cycle, as much as we all love it, really not benefit on at least some level from being, oh, 12 hours shorter?

Frankly, I think we hold hollywood to a higher standard than we hold art films. Art films can be boring or muddled or lose the thread of what they’re talking about, or be derivative of other movies, and they might just get dismissed. Make a hollywood movie that is based on another hollywood movie too closely, and you get derided as a hack and villainized. I mean, people _hate_ george lucas because of what he did to star wars, episode 1. Heck, they hated him for making greedo shoot first. People are much, much harder on Ang Lee for Hulk than they are on him for any of his other movies.

I think it’s wrong to say that it is irrelevant whether an audience likes a movie. I think that it is incorrect to say that commercial success is zero indication of quality. Sometimes it indicates quality very well. I think studio leadership is much more savvy and well-informed in its choices than you think they are, that they add more to the movies than you think they do, and that they are far less capricious than you make them out to be.

I know you’re no big fan of Shakespeare, but remember that he wrote almost every one of his great works for primarily commercial reasons. He did it for money. And I think if you delve depper into how foreign films are funded, you’ll see more money talking behind the scenes of a bergman or almodovar movie than your would expect. Not Money Talks money talking, but talking money nonetheless.

And it doesn’t seem quite fair to demonize studio heads for being profiteers and lionizing direectors as auteurs just by nature of their job titles when both work for money in the same film business and are often drawn from similar pools of people – and where it is not uncommon for one to become the other or vice versa. The relationship is not a one-way street, itls a negotiation. There are plenty of producers who care about making good movies, and even if they only cared about making entertaining movies audiences will pay to see, I fail to see why this is without value.

@Saint: I haven’t seen it, but from the reviews I read (and the violent reaction to the film at Cannes) it sounds like Antichrist, by Danish director Lars von Trier, might be an example of a nonsensical vanity project made by a foreign art-house filmmaker with basically unlimited creative freedom. Granted, it only cost $11 million to make, so we’re not in James Cameron territory here. But I think Belinkie and Fenzel are right: anyone, regardless of what country he or she is from, can make a crappy vanity project, especially if given too much freedom. But we perceive such a film as particularly crappy if it was supposed to be fluffy entertainment. In other words, if Lars von Trier screws up one of his crazy art films, there are enough people in the audience who will say, “Well, that was awful, but at least it was Art.” And if Ang Lee screws up the indie-comedy Taking Woodstock (which he did), it’s not as bad as if he screws up The Hulk, which was supposed to be a stupid-fun blockbuster.

If Lars von Trier wants to make a self-indulgent film, that is fine. He’s an artist, that’s what he’s SUPPOSED to do. But if James Cameron wants to make a self-indulgent film, and still sell it to John Q. Fanboy as the ultimate thrill ride, then we have a problem. Blockbusters have a RESPONSIBILITY to the audience. The question is, did James Cameron use his total freedom to make exactly the movie he wanted to make? Or did he use it to make the most entertaining film he knew how? There’s a difference.

I’m not sure whether this falls into the blockbuster or art category (maybe somewhere in between, actually, more like Shyamalan), but my favorite story of a writer/director’s creative control run amok is definitely Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate. After The Deer Hunter won five Oscars, United Artists decided they’d just bankroll him to do what he wanted. They gave him a wide berth and he still managed to go so far over time and budget that when the movie flopped hard it bankrupt the studio. It’s been in my Netflix queue for years and I still haven’t watched it, but my understanding is that it has something like a 20 minute long scene of people rollerskating in a barn.

Lest we forget, non-commercial filmmaking also leads to Uwe Boll.

Describing Antichrist as a ‘vanity project’ ignores the fact that von Trier has been doing pretty much whatever the hell he wants for many many years, with some amazing results (Antichrist included, frankly — if you watch it expecting a horror film you’ll probably hate it, but if you watch it expecting a von Trier film it’s better than either Dogville or Mandalay)… I’d agree that it’s the commercial part of the equation that makes giving absolute power to the likes of Lucas or Jackson (or Cameron) so dangerous.

Look at it this way: an art film only has a responsibility to be arty. Given what passes for art these days, that’s a pretty easy target to hit. Even if you make something awful, just so long as it’s confusingly awful or controversially awful or even just looks pretty, you’re in the clear.

A blockbuster has a responsibility to be entertaining. And while so-bad-they’re-good movies can muddy those waters somewhat, being entertaining is usually much tougher to pull off than being arty.

@Belinkie: the sort of fascinating thing is how Bamberger is initially really intrigued by Shyamalan and the project… and as the book goes on, he gets to know him, and realizes what’s going on, and that the movie is a dud. Shyamalan asks him toward the end what he thinks of the finished movie… and the best thing Bamberger can tell him is that it was just okay, but he appreciated all the effort and passion he had for the project. And Shyamalan seems kind of let down by that reaction… but you get the sense that deep down, he knows it’s the truth: he’s made a bad movie.

To that end, I think Shyamalan would have rather the book didn’t come out — but ultimately, it was his idea to have the writer document the process, so the fault rests with him. I think he knows his movie was a failure, so he can’t feel too burned. You get a good sense of that from the book.

If anything, I think the movie is a failure not because Shyamalan had absolute power to make what he wanted… but because he saw it as a “message” movie — and that message was, “How DARE you people think I’ve lost my touch as a filmmaker?! I’m one of the most innovative writer-directors working today!” It was a movie about settling a score against the people who didn’t think he walked on water any longer after THE VILLAGE disappointed. I mean… it was a RIDICULOUS act of hubris to not just make the hero of the movie a dispirited but ultimately miraculous Indian-American writer living outside Philadelphia… BUT TO CAST HIMSELF IN THE ROLE. We get it, Night… we get it.

@stokes

Have you watched a Uwe Boll movie with the director’s commentary turned on?

1) I highly recommend this experience. Uwe Boll is every bit as unintentionally hilarious as his movies are… but, more relevantly,

2( No one in the history of filmmaking has been more concerned with commercial concerns than Uwe Boll. His commentary is riddled with exposition about how he saved $50 by doing a shot in this particular manner, and how he took advantage of subsidy X in country Y. It’s quite astonishing that he doesn’t see how horrible the end product is when he is this concerned with all of this.

I realize that the article listing reasons why Avatar will suck was written before screenings took place, but there’s no excuse for this. Every since the embargo was lifted reviews have been pouring in, and they’re incredibly positive so far. 90% on Rotten Tomatoes from 42 reviews and Ebert gave it 4 stars. Those two things should be reason enough to actually reserve negative judgment until you see the film, let alone possibly get–dare I say it?–excited. Seriously, what’s with all the hate?

And then there’s the fact that we’re talking about James Cameron. I think the man deserves the benefit of the doubt. Out of the six non-documentaries he’s directed (I’m not including Piranha 2 for obvious reasons), half of them are in the IMDb top 250 (each of which is a decent way up the list too), and one of them is tied for the most Oscars wins of all time, along with making more money at the box office than any other movie in history. That’s a pretty impressive career, if you ask me.

Point is, when your other article was written, I didn’t look at it too kindly, but I understood that such negative skepticism toward Avatar was understandable. But at this point, I think it’s better to just save face and wait for the film to come out. Some pretty big publications are saying some pretty big things about this. I’m not saying that you have to get excited for it, but being apprehensive doesn’t mean you have to actively attack a film that you haven’t seen.

I’m not only saying this because I’m getting a bit sick of all the cynical attitudes toward Avatar, but because it’s starting to sound like this movie might really kick ass, and it sure wouldn’t make the site look too smart if they got caught taking cheap shots at what could still end up being the event movie of the year.