“I hope our wisdom will grow with our power, and teach us, that the less we use our power the greater it will be.”

“I hope our wisdom will grow with our power, and teach us, that the less we use our power the greater it will be.”

— Thomas Jefferson

—

“The spirit of enterprise, which characterizes the commercial part of America, has left no occasion of displaying itself unimproved.”

“The spirit of enterprise, which characterizes the commercial part of America, has left no occasion of displaying itself unimproved.”

— Alexander Hamilton

—

“Excuse me, I have to go. Somewhere there is a crime happening.”

“Excuse me, I have to go. Somewhere there is a crime happening.”

— Robocop

—

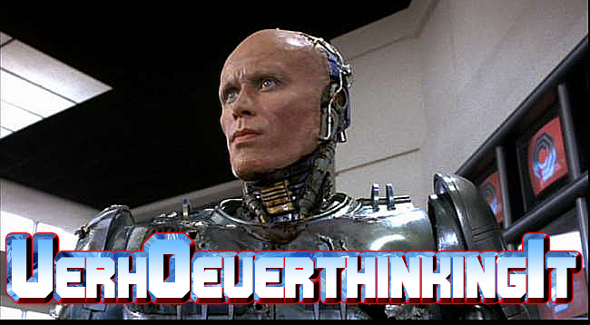

I had always intended for the second installment of this oldest and most waited-for (if not awaited) Overthinking It series to be about a character I have often described as the Quintessential American Tragic Hero: Alex Murphy, a.k.a. Robocop from the truly excellent Paul Verhoeven film of the same name. Then, of course, other things happened.

Well, this is VerhOeverthinking It week, and as Darren Aronofsky will hopefully showcase for us Robocop’s durability — both as a cinematic subject and as a cybernetic apparatus — so will I persevere in hewing to one of my earliest intentions on this site.

Let us venture into the glory, the flaws, the fall and the suffering of that bechromed bulwark of semivoluntary justice — the American who is Half Jeffersonian, Half Hamiltonian, All Cop.

Do you want to learn more? Well, dead or alive, you are coming with me —

Robocop’s tragic flaw

Every tragic hero has a hamartia — generally referred to as a “tragic flaw.” More accurately hamartia refers not to a quality of character or chance, but to a choice a character makes that carries with it often distant, often eventual, but still inexorable and dire consequences.

Alex Murphy was a happy, healthy husband and father living the American Dream in a beautiful home, far removed on its pleasant cul-de-sac from the city’s old-world indigence and desperation. He was humble, decent, smart, capable, handsome — everything you might expect from an American square-jawed hero, past, present or dystopian future. He was at once living the dream and achieving a great height from which to fall.

But Alex Murphy had a hamartia, a tragic flaw — he committed himself to the Old Detroit police force. He saw the injustice and evil in the world, he saw the abuse that Old Detriot was suffering at the hands of its criminals, and he felt the need to do something about it. He was going to make Detroit safe. Talk about hubris!

Every day, Murphy left his home and involved himself in the problems of others. Every day, he served as the teeth of the grinding gears of power. Not-quite unbeknownst to our hero, the giant institutions that paid his salary ostensibly sought, to make the city a better place, but below the depths, themselves through inadequacy, dysfunction and corruption, mired themselves in the problems and worsening them for their own benefit.

And for this commitment, Alex Murphy suffers dire punishment from Cruel Fate. While attempting to break up an organized crime ring financed by and in cooperation with the same institutions that pay his salary and own his city, Alex Murphy is gunned down as a man — and resuscitated as a cyborg. Wired to a nearly indestructible body that whirs audibly whenever he walks, all that remains of him is the virtue, talent and skill — along with the his tragic choice — that he brought with him and cultivated on the force. His memories, his name, his home, his beloved wife and child, all are taken from him as he is made “half man, half machine, all cop” — a soulless avatar of his commitment to protecting that which for him no longer exists.

Just as the Hobbits in The Lord of the Rings speak to a British national experience, intentionally or no, in their retreat from matters imperial to their shire after learning their own courage and capability, or Goethe’s Faust speaks to the self-destructive spirit and legacy of German ingenuity and passion — so does Robocop speak to America’s great Pyrrhic victory: the doughboy going “over there” to defeat the enemies of homeland and liberty with talent, strength, ingenuity and the fruits of prosperity — only to find himself enmeshed overseas in body and spirit, never to truly go home, never to be truly free again to choose to stay or go.

Look for musket balls recast from family pewter in the sites of Revolutionary War battles, and you will find an America that starts with plowshares and beats them into swords.

And what is Robocop but the fusion of scrap tin for the war effort with the Boy Scout who knocked on doors and scoured the town to collect it?

“[Verhoeven is] like De Tocqueville with brief nudity and a higher body count.”

WIN.

Also, video punchline at the end = WIN

Great article.

It isn’t pop culture, but another great depiction of the American tragic hero can be found in Arthur Miller’s play A View From The Bridge.

Just read Perich, Stokes, Belinkie, Lee and now this…I’m loving Verhoeverthinking It with a level of intensity it definitely deserves.

PS – OT @Fenzel: can you do a post on the syntactic genius of the Wu-Tang Clan such that they can make this sentence:

Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nothin ta fuck with.

actually mean this sentence:

Wu-Tang Clan is nothing to fuck with.

The laws of grammar and double-negatives dictate that the first sentence should mean that the Wu-Tang Clan is not nothing to fuck with, i.e. that the Clan is indeed something to fuck with.

However, any listener immediately takes the second sentence as the true meaning.

How is this possible?