First of all, if you ever intended to sit down on a beach somewhere and enjoy John Philip Sousa’s 1902 novel The Fifth String, stop reading now. This is going to be a spoiler-heavy review. (If you do want to check the book out yourself, the etext is available here.)

As you might expect from America’s foremost bandleader, the novel is about a musician. As you might NOT expect, it’s about a violinist. But it turns out that violin was Sousa’s first instrument, and always one of his best. So there.

As you might expect from America’s foremost bandleader, the novel is about a musician. As you might NOT expect, it’s about a violinist. But it turns out that violin was Sousa’s first instrument, and always one of his best. So there.

The violinist in question is Angelo Diotti, a famous virtuoso arriving in New York to make his American debut. On the night before the performance, he attends a party and instantly falls in love with the daughter of a prominent banker:

He seemed hypnotized by the vision, which moved slowly from between the blue-tinted portieres and stood for the instant, a perfect embodiment of radiant womanhood, silhouetted against the silken drapery.

Don’t worry – I had to look up “portiere” too.

But if you don’t dig this Late Edwardian flowery prose style, than The Fifth String might be the longest 150 pages you’ll ever read:

“A desire for happiness is our common heritage,” he was saying in his richly melodious voice.

“But to define what constitutes happiness is very difficult,” she replied.

“Not necessarily,” he went on; “if the motive is clearly within our grasp, the attainment is possible.”

“For example?” she asked.

“The miser is happy when he hoards his gold; the philanthropist when he distributes his. The attainment is identical, but the motives are antipodal.”

“Then one possessing sufficient motives could be happy without end?” she suggested doubtingly.

“That is my theory. The Niobe of old had happiness within her power.”

“The gods thought not,” said she; “in their very pity they changed her into stone, and with streaming eyes she ever tells the story of her sorrow.”

“But are her children weeping?” he asked.

That’s some epically poor flirtation. And I should know.

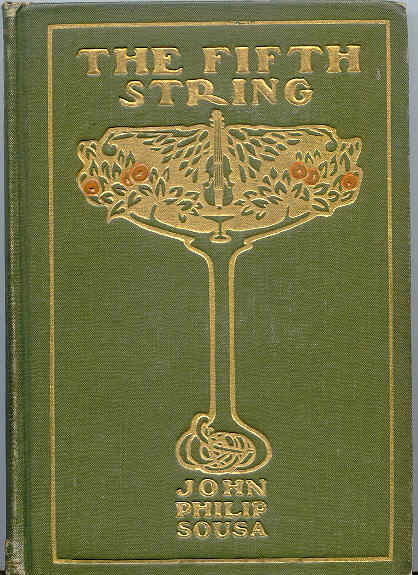

(By the way, all illustrations in this post are taken from the first edition of the novel.)

The conversation moves to the euterpean muse, at which point Miss Wallace reveals she has never been emotionally affected by music:

“I never hear a pianist, however great and famous, but I see the little cream-colored hammers within the piano bobbing up and down like acrobatic brownies.”

At first, I was afraid “brownie” was a horribly racist allusion. But after Wikipediaing it, I’m pretty sure Sousa meant this. I got to say, for a guy who got his education in the Marine Corps, he knows his mythology. Semper Fi.

Anyway, Diotti plays his concert to thunderous applause, but Miss Wallace seems unmoved. The poor violinist is crushed, and promptly abandons New York. He goes to the Bahamas, rents an island, and starts to practice night and day. Personally, I question if the best way to win the heart of someone who doesn’t care for music is by trying to improve your double bowing. Maybe he should find out what she DOES care about? Just a thought.

Finally, after Diotti spends weeks striving to produce music more beautiful than any the world has ever heard, the novel gets down to business:

Extending his arms he cried, in the agony of despair: “It is of no use! If the God of heaven will not aid me, I ask the prince of darkness to come.”

A tall, rather spare, but well-made and handsome man appeared at the door of the hut. His manner was that of one evidently conversant with the usages of good society.

“I beg pardon,” said the musician, surprised and visibly nettled at the intrusion, and then with forced politeness he asked: “To whom am I indebted for this unexpected visit?”

“Allow me,” said the stranger taking a card from his case and handing it to the musician, who read: “Satan,” and, in the lower left-hand corner “Prince of Darkness.”

The business card is a nice touch. If you’re going to have the devil show up in human form, you can at least give the audience a wink to show that you know it’s a little silly, even by 1902 standards.

Satan wants to give him a violin – sadly, not the fiddle of gold that he would later offer down in Georgia.

“Allow me to explain the peculiar characteristics of this magnificent instrument,” said his satanic majesty. “This string,” pointing to the G, “is the string of pity; this one,” referring to the third, “is the string of hope; this,” plunking the A, “is attuned to love, while this one, the E string, gives forth sounds of joy.

…

“But that extra string?” interrupted Diotti, designating the middle one on the violin, a vague foreboding rising within him.

“That,” said Mephistopheles, solemnly, and with no pretense of sophistry, “is the string of death, and he who plays upon it dies at once.”

“The–string–of–death!” repeated the violinist almost inaudibly.

(The old man in the illustration, by the way, is an unnamed character who enters at Satan’s command, presents the violin, and leaves. Your guess is as good as mine.)

It’s a bit of a fudge on Sousa’s part that the first four strings inspire emotions in others, but the Death String causes only the death of the player. But hey, it’s a Satanic violin – no one said it was going to be logical.

And in case you think you’re more clever than Sousa, no, you can’t cut off the String of Death, because then the other strings would stop working. Without death, there can be no hope, joy, or love. Get it?

Despite his modus operandi, Satan doesn’t ask for anything in return for the instrument. He hands it over, no strings attached, so to speak.

Diotti makes his triumphant return to New York, and announces a new set of shows. The lovely Miss Wallace attends, and hears Diotti play a solo piece of his own composition:

Grander and grander the melody rose, voicing love’s triumph with wondrous sweetness and palpitating rhythm. Mildred, her face flushed with excitement, a heavenly fire in her eyes and in an attitude of supplication, reveled in the glory of a new found emotion.

In every story I’ve ever read in which someone uses magic to manipulate someone else’s emotions, it’s always a bad thing. It’s either something that the bad guy does, or the good guy tries it and realizes that magically-induced love isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. But Diotti doesn’t hesitate to win Mildred’s heart via the String of Love, and you get the feeling Sousa doesn’t want us to question how genuine her affection is.

Then Mildred’s father, Mr. Wallace, returns from Europe. He’s none too thrilled about his daughter marrying a musician, and confers with his banking crony, a guy by the name of Sanders. Sanders attends Diotti’s performance, notes the mysterious fifth string that is never played, and decides he can use it to make Mildred jealous. I know what you’re thinking: “How do you make someone jealous via unorthodox violin design?” Observe:

“I recall a strange story of Paganini… he became infatuated with a lady of high rank, who was insensible of the admiration he had for her beauty.

“He composed a love scene for two strings, the `E’ and `G,’ the first was to personate the lady, the second himself. It commenced with a species of dialogue, intending to represent her indifference and his passion; now sportive, now sad; laughter on her part and tears from him, ending in an apotheosis of loving reconciliation. It affected the lady to that degree that ever after she loved the violinist.”

“And no doubt they were happy?” Mildred suggested smilingly.

“Yes,” said the old man, with assumed sentiment, “even when his profession called him far away, for she had made him promise her he never would play upon the two strings whose music had won her heart, so those strings were mute, except for her.”

The old man puffed away in silence for a moment, then with logical directness continued: “Perhaps the string that’s mute upon Diotti’s violin is mute for some such reason.”

The next time Diotti sees Mildred, it only takes about 10 seconds before she asks him to cut off the fifth string. He refuses, and she throws a nice little hissy fit.

“Go,” she said, pointing to the door, “go to the one who owns you, body and soul; then say that a foolish woman threw her heart at your feet and that you scorned it!”

I should mention that her obsession with the string is helped along by the fact that it’s woven from the hair of Eve. A nice touch, it being the String of Death, added after the Fall.

Mildred makes Diotti an ultimatum – if he won’t cut the string off, at least he’s got to play it.

“I will watch to-night when you play,” she flashed. “If you do not use that string we part forever.”

No great mystery how this one goes down.

Suddenly the audience was startled by the snapping of a string; the violin and bow dropped from the nerveless hands of the player. He fell helpless to the stage.

Mildred rushed to him, crying, “Angelo, Angelo, what is it? What has happened?” Bending over him she gently raised his head and showered un- restrained kisses upon his lips, oblivious of all save her lover.

“Speak! Speak!” she implored.

A faint smile illumined his face; he gazed with ineffable tenderness into her weeping eyes, then slowly closed his own as if in slumber.

The End.

The book actually has a fair amount of similarities to one of Sousa’s marches. It’s brief, it has a rigid structure, and it’s completely predictable. Nevertheless, it does have a certain charm. I could imagine this making a serviceable episode of The Twilight Zone, or at least Tales From the Crypt.

Throughout his life, Sousa continued to write fiction – five novels in total, according to Wikipedia. None of them are in print today. But whatever posterity thought of Sousa’s books, it’s worth noting that he always seemed pretty proud of them. A researcher pointed out that in one of Sousa’s official Navy documents, he listed his occupation as “Composer, Novelist, Conductor of Sousa Band.” Sousa had written that at the age of 63.

“The book actually has a fair amount of similarities to one of Sousa’s marches.”

Yes, but do I have to play off-beats throughout the entire frikin’ thing?