The opinion that the Oscars are “out of touch” with the movie-going audience is neither a new idea, nor one that’s lacking in evidence. The day after the 2015 Academy Awards ceremony, the New York Times ran a piece with the headline “Oscars Show Growing Gap Between Moviegoers and Academy” and cites the minuscule audience for Best Picture-winning Birdman and the dwindling ratings for the telecast as evidence. Back in 2009, we ran a piece that looked for statistical evidence to this effect. For the better part of the last three decades, people have been complaining about “Oscar bait” movies and their disconnect from mainstream fare. It’s effectively common knowledge now.

So just to pile onto the already large body of evidence, I’d like to revisit–likely for the last time–my series of statistical analyses of Oscar speeches, specifically, the part of the analysis that looks at usage of the word “movie” versus “film.” For those of you who are new to this, here’s as quick history: starting in 2010, I ran the collective body of Oscar acceptance speeches through a text analysis tool to see what, if anything, they revealed about the collective thoughts of Hollywood’s elite. I found all sorts of interesting things (like the near-total absence of shout-outs to God) but eventually my analysis was almost completely overshadowed by Slate’s blockbuster interactive data visualization of Oscar speech content.

Almost completely overshadowed. Last year I dug a little deeper into this idea that Oscar winners’ preference for the term “film” compared to “movie” reflected the Academy’s disconnect from the mainstream. The article itself and the comments explore the idea that this may be due in large part to the fact that “movie” is a predominately American term and that the heavy presence of Aussies and Brits receiving awards tilts the scales towards usage of the word “film.”

So this year, I added some nationality data to our analysis of the “movie” versus “film” divide.

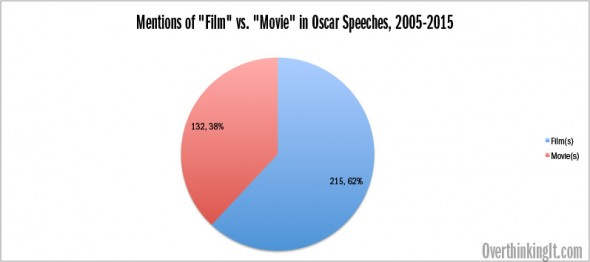

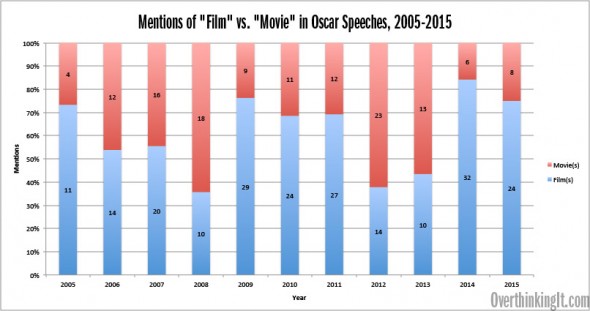

First, here’s the updated trend on Oscar speeches’ usage of “film” versus “movie” from 2005 to present:

There’s no real discernible trend over time, but it is clear that over the years, the majority of references have been to “film.” What the hell, here’s a pie chart that illustrates this more clearly:

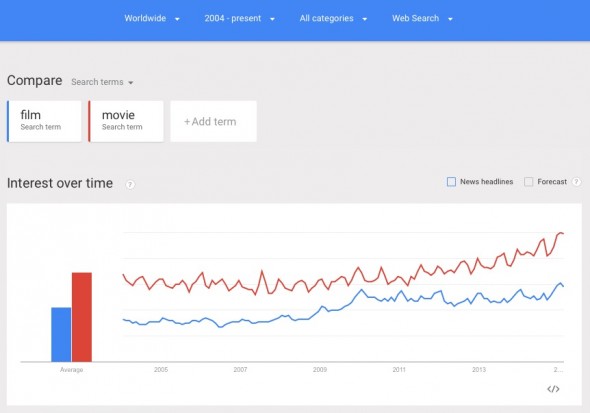

Now, let’s see how nationality plays into this. In 2014, Non-American Oscar winners outnumbered Americans by a 24-18 margin. I don’t have the numbers handy for 2015, but I would expect the ratio to be similar. Remember that we’re working off the assumption that, outside of America, the word “movie” is not commonly used. Google Trends tells us that this is may not actually be the case: from 2004-present, worldwide Google search queries indicate that “movie” is a more common search term than “film”:

Now, let’s see how nationality plays into this. In 2014, Non-American Oscar winners outnumbered Americans by a 24-18 margin. I don’t have the numbers handy for 2015, but I would expect the ratio to be similar. Remember that we’re working off the assumption that, outside of America, the word “movie” is not commonly used. Google Trends tells us that this is may not actually be the case: from 2004-present, worldwide Google search queries indicate that “movie” is a more common search term than “film”:

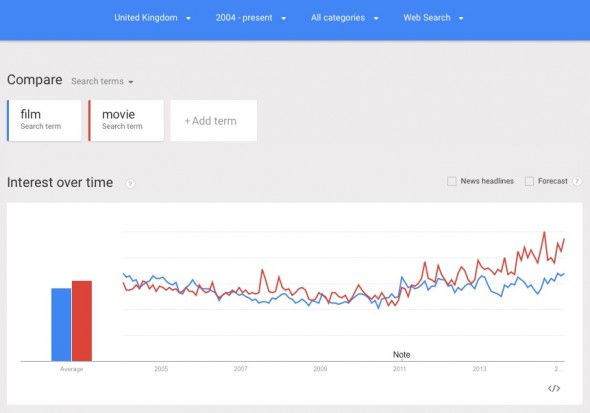

This is true even in the United Kingdom. The two terms are nearly at the same search volume, but “movie” still beats out “film” (although this wasn’t always the case):

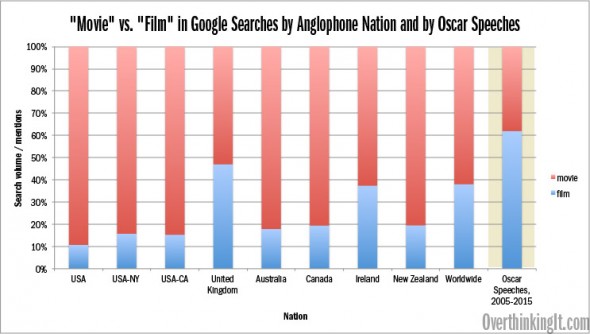

Now, let’s stack up the rest of the Anglophone nations and their Google search habits next to all of the Oscar speeches over the last 11 years:

I also threw in New York and California, distinct from the rest of the US, to see if there was much of a difference in the media capitals of the East and Bleeding Coasts compared to the rest of the country. There is a tiny difference, but not much. The big takeaway, of course, is that Oscar speechmakers reference “films” at a rate far greater than Google searchers from any Anglophone country, including the “film”-loving UK.

So what can we draw from this? Well, to the extent that Google searches are indicative of linguistic usage patterns, it does confirm that “film” is in fact much more commonly used in the UK than the parts of the world (though no Australia) and that Oscar speech-givers say “film” more often than people do Google searches for it. The finding is definitely in line with the broader thinking around the Oscars being out of touch with mainstream tastes.

But before we get too carried away with this data, let’s remember that these speeches aren’t given in a vacuum, and that they may not even be indicative of how these Oscar winners might refer to their work on a day-to-day basis. Context matters; specifically, the name of the award categories themselves. Four of the 24 contain the word “film,” one contains the word “picture,” and none, of course, contain the word “movie.”

I do of course realize that I’m probably reading way more into this whole “movie” vs. “film” distinction that is probably warranted, which is why this will probably be the last year I conduct this analysis. But the conversation around the disconnect between popular “movies” and award-winning “films” should absolutely go on. It’s not inconsequential; there’s a lot at stake when an authoritative body that holds such massive influence over our culture passes value judgments on creative works that mean a lot to us. And it’s unfortunate when the overall tenor of this event seems to devalue–shame, even–entire genres of creative output that brought so much joy to so many people. The entertainment establishment may own the mechanism to produce “films” or “movies,” and they may control their own process for handing out fancy awards, but we, the audience, are equally important stakeholders in this grand storytelling project. And that’s why we care about these silly awards and the language that’s used to talk about them. Film, movie, motion picture–whatever they’re called–we want them to be worthy of the awesome power that we give them in our lives. We want them to be good, and for the good ones to be recognized as such. Is that too much to ask for?

Add a Comment