A Man’s Allotted Years

The idiosyncratic nature of professional soccer becomes more obvious when you consider timekeeping.

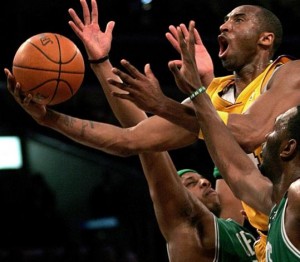

A game of gridiron football has four 15-minute quarters with an intermission for halftime. The clock stops after certain plays, most often to retrieve the ball or adjudicate a penalty. A game of professional basketball in the U.S. has four 12-minute quarters, again with a halftime and a stopped clock for fouls. Ice hockey periods are 20 minutes long and there are three of them. When the clock runs out, whoever has the higher score is the winner.

(Baseball is the odd duck here, as one of the few competitive team games with no clock whatsoever. A game takes as long as it takes. The current MLB record is a twenty-five inning slugfest between the Milwaukee Brewers and the Chicago White Sox in May 1984 that lasted for eight hours and six minutes. Baseball’s odd metaphysics merit their own post, which you might get once the World Series comes around. For now, we have to set baseball aside, for reasons that’ll become clear below)

Soccer hews to the same principles as the above sports, with one small exception. But this exception makes a world of difference.

It's the FINAL COUNTDOWN!

If a player is substituted, a foul is called or an injury is suffered – in other words, circumstances under which the clock would stop for other sports – the clock continues running. The referee keeps track of the time lost in this way. At the end of the match’s 90 minutes, the referee indicates that play will continue in stoppage time. The referee doesn’t need to say how much more time is on. He can give a rough indication, but he remains the sole arbiter of how much time is left.

To state it plain, the players do not know when the game is going to end.

Anyone who watches professional sports knows that the caliber of play changes as the half nears its end. Gridiron football teams have their “two-minute drill” – an accelerated routine designed to get in as many plays as possible before halftime. Professional basketball slows down in its final minutes: fouls become frequent, as players would prefer to give up one point and get the ball back than risk their opponents scoring two or three points. Everyone has their eye on the clock. The pace ramps up. The tension mounts.

If we consider the players and their coaches as rational actors – homo economicus – this doesn’t make any sense. There’s no mystery to when an NBA game is going to end. It would be far more rational to pace yourselves over the entire 48 minutes of play rather than play loose in the first quarter and draw lots of fouls in the second. But humans do few things rationally, including games.

A game has a clock to distinguish it from the real world. The clock creates arbitrary boundaries around a set period of events and says These Events Will Count. It doesn’t matter how well Paul Pierce and Kevin Garnett of the Boston Celtics scrimmage. If they can’t score more points than the Los Angeles Lakers during the 48 minutes that the NBA says they’re going to play, they lose. Conversely, the Lakers could have outplayed the Celtics all season. They could have defeated every team that beat Boston. But once they show up on the court, only those 48 minutes matter.

Pardon me.

Real life, obviously, has no such boundaries. We create milestones for ourselves: graduating high school, losing our virginity, graduating college, getting a job, getting married, having a child. “Once I reach this point,” we say, “I’ve made it.” But what we find, as we grow older, is that the flush of success fades. We reach the milestone, but the story refuses to end. The day after you graduate college, you still have to get up in the morning and figure out what you’re going to do with yourself. Sports have quarters and halves; life does not.

Unless you’re playing soccer.

Soccer’s interesting in that it doesn’t have a clearly defined end point. A game is supposed to take 90 minutes, but stoppage could add anywhere from a few seconds to a few minutes onto the end. And referees are allowed to be vague about how much. Considering how close soccer scores often are on the professional level, this new lease on life creates a fresh outlook. Optimistic teams can look on the time added on with hope: another chance to score! Another opportunity to triumph over the pseudo-death that is defeat! Pessimistic teams, on the other hand, treat stoppage time as a curse. How much longer must we labor? When can we put down our ploughshares and receive our just rewards?

The U.S.’s fate in the 2010 World Cup rose and fell with stoppage time. Landon Donovan’s goal against Algeria in the 91st minute sent the U.S. to the second round to face Ghana. But against Ghana, the U.S. gave up an early goal in the first overtime period. When two minutes and fifty seconds of stoppage time were added at the end of overtime, the U.S. played with little heart, rather than seizing the new opportunity. Destiny gave with one hand and took away with the other.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OWgi6NO37Y4

Though science continues to advance, we never really know when a life – or a soccer game – is going to end. And we never really have the chance to turn back the clock – or take back a bad call in soccer. Soccer is the game most like life.

Perhaps this is why soccer has such enduring popularity around the world. It’s played on every civilized continent. It’s played between states that don’t always trade with each other. Even in the U.S., where professional soccer has none of the cachet of gridiron football or pro basketball, kids play rec league soccer in each of the fifty states. Why? Maybe because kids still live without cynicism. They don’t need an arbitrary set of rules to tell them when to stop and start play. They don’t need rigid boundaries in which they can excel, after which they shower off their sweat and resume their quotidian lives. Kids will play as long as they’re allowed to. They don’t demand do-overs or official review. They don’t care when the game’s supposed to end. They’ve got a ball, two goals and a team of whoever shows up.

That’s soccer. Or the world we live in.

Pedantic note: you discuss the thermodynamic arrow of time, but display a graphic discussing the cosmological arrow of time, which is a distinct notion–in fact, there is a solid argument to be made that the cosmological expansion of the universe during the dark energy phase, by adding net energy to the universe, will ultimately prevent heat death in the Big Rip. Not to mention a bunch of other possible scenarios for the birth/death of the universe.

“It’s always been something of a mystery why soccer hasn’t caught on as big in the U.S. as it has in the rest of the world.”

American exceptionalism. This is pretty obvious, but the term has different definitions depending on who is using it, so I will try to provide more explanation (plus this is Overthinking It).

Compared to most countries, the US was really isolated in the nineteenth century. With no planes, phones, and internets the oceans were a real barrier. So all sorts of things developed in American culture that you didn’t have elsewhere. We developed three sports, baseball, football, and basketball, that proved more than sufficient for whatever purposes sports are supposed to serve.

Soccer was an English sport that was spread around the world mostly by English and Scottish workers, who would travel throughout the British empire and South America to do things like build railroads. Americans built their own railroads, and so this wasn’t a factor. Its really more of a mystery why soccer never caught on in Canada and India. But it never caught on the U.S. for the same reason rugby never caught on in the U.S.

Now when this period of relative isolation ends, with World War I and more definitively World War II, the U.S. is a superpower. It is the most successful country on Earth, both politically and economically, with the highest standard of living. Americans didn’t import cultural things from other countries -in fact it was a point of pride that we didn’t- instead we exported our culture.

So the willingness to get interested in something like soccer is really a sign of relative weakness. Like in other areas, the U.S. is becoming a net cultural importer instead of net cultural exporter. This is why the American right hates soccer, and they have a point.

However, its fun game, plus growing American interest in soccer is happening at the same time the rest of the world has been adopting two of the American-made sports, basketball and baseball. This might stop if globalization goes in reverse, but it seems a fair exchange to me.

OK, I read the whole post. Jesus Christ.

First, the whole argument seems to be that Americans don’t take to soccer because Americans uniquely value fair play. I don’t think I’ve read any other analysis of American culture that said that fair play is a strong element of it. The United States is a Matthew society (Matthew 3:12 “To him who has, more will be given”).

Second, apparently now hockey is an American sport but baseball isn’t.

Then there is the issue of other sports putting in replay and review only recently, after which soccer became more popular here.

because Americans uniquely value fair play.

I think Americans value the appearance of fairness (while still stacking the deck in their favor) more than actual fairness.

And like I said re: baseball – baseball is weird. But at least in baseball you know what has to happen for the game to end. There’s never a chance the umpire will run on the field with 2 outs left in the 10th inning and say, “All right, everyone stop playing. The Yankees are up now, so they win.”

@Valatan: we encourage pedantry! I may update the image later.

Okay, it’s detecting repeat posts without actually showing my post…

Perich, I very much enjoyed this article. That said, I would be derelict if I didn’t post this link from Newsweek:

http://www.newsweek.com/2010/07/03/soccer-is-not-a-national-metaphor.html

@Timothy: I’m not seeing any other comments by you in the queue. Um – try posting it again? Sorry? :\

I dig it, nice take on the game. Seems like everyone wants to put a metaphysical spin on the ol’ Jabulani –

http://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2010/06/metaphysical-club-soccers-talismanic-heroes/58785

There’s lots of reasons soccer is popular while there are several other sports that are distinctly American. One that hasn’t been mentioned here yet: soccer is cheap. At its most bare, you just need a ball and the ability to take off your shirt and use it for a boundary marker. American football requires expensive protective gear; basketball requires pavement and hoops, neither of which can be easily improvised; and hockey requires an ice rink, which just isn’t gonna happen unless you’re in a really cold country. I suspect this has a lot to do with why soccer’s the most popular sport in third world countries.

I don’t really buy the “Americans like fairness” argument, a perhaps related argument that I find more convincing is that Americans like logical progressions, sequences, and systems that can be empirically and statistically analyzed. Baseball has strikes, balls, outs, innings; football has the downs system, but soccer just flows freely in between goals, which, perhaps, unnerves people. (I know I don’t like that aspect of soccer particularly.)

I don’t think you’re right about the fact that it’s irrational to play differently towards the end of a period in basketball or football–the part you’re missing is risk tolerance. This is perhaps most clear in the Football example. The two minute drill is a very risk-seeking play. You’re a lot more likely to score in a short period of time, but you’re also a lot more likely to throw an interception or turn over on downs. Throughout most of the game, both teams are probably roughly risk-neutral–they want to maximize their expected return in terms of points (although there are a number of behaviors, like failing to go for it on fourth down that are conventional but insanely risk-averse, but that’s a whole different plate of spaghetti). The calculus changes completely as the clock ticks down–suddenly one team is ahead and the other behind. Losing by one point and losing by seventy points is basically the same thing, setting aside oddities like the coach’s polling in college football. Therefore, a team that is behind towards the end of the game should become very risk-loving with regard to points–there is virtually no downside risk for them (they can’t lose any more than they already are) and all the upside potential in the world. The leading team is in the opposite situation. Teams who are ahead in the last couple of minutes of the game do not break out the two-minute drill–they run out the clock sacrificing upside potential in terms of points for a lower downside risk of the other team scoring. Basketball has some different issues–the fact that there’s no need to “save up” time outs or fouls before fouling out when the game is almost over. While there is certainly irrational behavior in sports, the fact that play changes when the clock ticks down is not part of it.

I think that America’s distaste for soccer does have to do with fairness, but in a completely different way. One major difference between soccer and the American sports is that soccer tends to have very low scores. In basketball, if one team plays better, that is directly represented in the scores because it will average out over so many points. Football is a game where all but the biggest mistakes are largely forgiven; if you get no yards on a play, you’ve still got three more to make it. And baseball’s weird. The point is, these games are about consistent effort that slowly stacks up to victory.

Soccer, meanwhile, can at least appear to be ridiculously luck-based. A shot that hits the post would have gone in if kicked just slightly differently. Corner kicks are essentially the ultimate in luck: the ball flies in and a whole crowd of people all jump for it at once. Maybe a defender clears it, or maybe an attacker knocks it in. But the random nature of it, I think, does not suit Americans. America is all about the idea that consistent hard work and excellence are the keys to success. Although soccer takes consistent hard work, that hard work seems to have the purpose of creating opportunities for getting lucky, and frankly this is a hard truth of the world that the American culture tries to deny: even if you work your ass off, you still need to get lucky. And that’s just not fair.

@CG:

You don’t find American football insanely prone to luck, at least relative to soccer? Miracle touchdowns that turn the course of games? Or that arcane tuck rule that makes no logical sense, the more I think about it? Or, for that matter, the fact that you’re limited to two challenges, win or lose?

First off, really nice post!

Second, @Ed: Although this may not be the place for international disputes, I have to point out that the US does NOT have the highest standard of living in the world. It may be the strongest political and economic player, but if you take various measures for standard of living (like GDP per capita, etc.), the US is usually at rank #5-10. See for example:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_GDP_(PPP)_per_capita

There simply is too much poverty within the US population to occupy that top position in the world.

Third: As a European soccer fan, I say that the one thing they should change is introduce electronic goal recognition: build a chip inside the ball and sensors inside the goal posts, and let the electronic magic work to tell you EXACTLY when and if (or if not) there was a goal scored or not. Considering the huge luck factor, and the immense weight that lies on a single goal in a match (again, different from American football or basketball), this would make it a lot fairer, as in the England-Germanny match. And I say that as a German!

As for official review: It is true that introducing this would really change the game, because it would also mean you need to introduce clock stopping.

Fourth: I think the real difference between soccer and other sports is the amount of weight you put on the referee in interpreting the rules. American football and basketball rely much more tight, “objective” interpretation of rules – and that’s why you need “technology” like clock stopping and official review to enforce the rules). Soccer, on the other hand, relies much, much more on the ref’s calls.

When I watch soccer games with friends, and the instant replay shows for example an offside that the refs didn’t call, someone usually solves the argument of whether or not it was offside with the claim: “It is offside when the ref calls it offside”. Which is true!

In a similar way, it is not true that in soccer there is no way of knowing when the game ends: It simply is over when the ref calls it.

I think there’s a lot in some of the posts. Certainly, I’ve heard arguments about American Isolationism/Exceptionalism before.

I’ve also heard the argument that CG makes before, suggesting that ‘American sports’: a. have a lower luck percentage than ‘European sports’; and b., are based more on the regimented repetition of key tasks. Certainly, American sports superficially appear to be more regimented and attritional than others: compare the rounded tracks of NASCAR to the street circuits of Formula One; the relative success of Americans in short, regimented sprinting events compared to their almost complete absence in longer distance races; the tennis of Andy Roddick versus the tennis of Rafa Nadal. The basic claim being that Americans like to reward the successful, quality achievement of a simple task compared to a more European (read also African and South American) taste for a chance-prone continuous flow of activity, in which errors will occur, but moments of ‘the beautiful game’ will also appear (genuine question: can Baseball or Basketball ever be beautiful?).

Baseball umpires retain a lot of the same subjectivity as soccer referees, and while modern professional baseball games have 9 innings, when people play them on their own terms, the number of innings tends to vary, and you often just play until there isn’t any more time.

The strict use of clocks in so many American sports is probably more a consequence of the power and influence of the American railroad industry, which is what made clocks necessary in the first place.

Americans never caught on to soccer because football took up the same niche — the proliferation of soccer was supported in its early days by its adoption in British schools — American schools picked up American football instead, and by the time it became apparent that a random English game was going to become a global sport, Americans had already figured out which sports they liked and there was no need to change that.

American football, Aussie Rules football, rugby, and soccer all have common ancestors in England — there used to be a bunch of variants of football (“rugby football” was one of them) and Americans and English came up with the notion to standardize the rules at roughly the same time – in the mid 1800s.

The English went one way, separating “football” and rugby and setting up specific rules for each, and the Americans went another way, changing rugby enough that it eventually became a different sport entirely.

(Although most of those changes were gradual. The story of the forward pass is pretty interesting — American football didn’t used to have forward passes, but because the line of scrimmage setup made the “scrums” really fixed and intense, without the fluidity of rugby, kids in college teams were dying in football games. The group of people in charge of the rules first wanted to make the field wider, so people could run around the blockers more easily, discouraging up-the-middle plays — but Soldier Field at Harvard had already been built at great expense, and it was too narrow to accommodate a wider field. So, Walter Camp invented the forward pass.)

The oldest American football college rivalries are about as old as the oldest British soccer tournaments — they all started in the 1870s; which, by the way, was right after America had a big Civil War, was heading into a series of giant financial panics, and wasn’t particularly interested in foreign influence.

So, in America, you have three main sports — football is the sport they played in colleges, baseball is the sport they played on farms and in rural or suburban areas, and basketball eventually became the sport they played in cities and gymnasiums. Hockey was around, of course, but it’s always been more of a Canadian sport than an American sport — and of course, it is played on ice, which meant for a long time it was only played in certain places.

Each of these sports had big stars that were part of the marketing pushes that popularized them and made them “professional” — but they all took root in the public consciousness long before they were professional sports.

It’s not like soccer is older than these sports — baseball is of similar ilk to cricket and modern baseball predates modern soccer by a good 30 or 40 years (a very important 30 or 40 years in American history).

So, why would people who are already playing a modern sport adopt a new one en masse? I’d understand why, in a place where games were traditional and ad hoc, you’d want to adopt a new sport with standardized rules that you could play against people from other towns, and I understand why colonists would bring their game to their imperial possessions, or why post-colonial authorities would look to sports played back at the mother country for ideas on what to do with themselves — that explains why soccer spread so widely to so many places, as well as tennis — but America had already been independent for a hundred years, it already had modern sports with standard rules before soccer even got started. Why switch to a different variant of the same game?

Kids play soccer in the United States en masse because it isn’t safe for them to play American football yet. As soon as they get old enough to play American football, the relative popularity of soccer collapses. I don’t think it has to do with the values associated with each game.

I’m a firm believer in the notion that the circumstances that exist when something enters the culture, the economy, the world, persist and influence what happens for long afterward. A lot of the structural circumstances around race and gender in America have less to do with contemporary attitudes and more to do with the circumstances from a hundred years ago that still stick with us, because old habits die hard.

And @Rob, yes, baseball and basketball can both be very beautiful. Basball in particular is a phenomenally beautiful game — but it doesn’t play nearly as well on television as it does in person. The beauty of baseball is contingent on the park it is played in — its geometry, its slight asymmetries, the relationship it has with the surrounding area — because of its markings, shape, and cleanly separated, different textures of earth, a baseball field creates a strong impression that a soccer field or American football field, or even a basketball court really doesn’t. It has a quality of timelessness. A baseball field is a suspended space, almost hallowed ground.

Most of the great, beautiful moments in baseball involve the park in some way. Willie Mays deep in the outfield, racing backward into the sea of green, making his basket catch. Mickey Mantle smashing the light at the top of Yankee Stadium. Babe Ruth’s called shot, pointing out over the fence. The vibrant trigonometry of the double play. The arcing slider grazing the corner of the plate. The rising dust and sound of a slide — even the oiled leather of a glove. Baseball is about the place and what is there more than it is about the people in it, and it can really only be appreciated live.

Basketball has the good luck of being one of the most beautiful games if viewed in slow motion — the acrobatics, the leaping, the urgency presented by the proximity and position of the basket. Dazzling dribbling skills, which are as artful as those in soccer, and made the more kinetic by impact with the gruound. Playing it, you get a sense for all these, but if you’re watching it from far away at full speed, the beauty of basketball is kind of lost.

@Rob:

The dominance of non-Americans at distance events is a relatively recent phenomenon. When Alberto Salazar, the last American citizen to win the Boston Marathon, won in 1982, the US had long been a dominant force in distance running.

A little late to the party.

The topic of instant replays has come up at least once a day on ESPN between the hours of one and four (on the west coast). But that demand seems strictly (or at least mostly) to be an American one. And I’d argue it doesn’t really matter much, because if you look at the goals in question during this World Cup, they wouldn’t really have won the games for the teams they were “taken” from. If they demoralized the teams, well, that’s the fault of the players, not the game mechanic or rules. So I’d agree, if Americans want replays and stoppages, we’re going to have to take soccer more seriously in general- but I also think it’s really arrogant for Americans to demand an entire system change because it doesn’t fit the way *we* play all our other sports. World Cup football isn’t Americn-style sports, it’s an international event, and Americans need to respect that and, if necessary, endure under the international standards. (I’m opinionated, yes. But I’m not anti-American- the avatar isn’t meant to be ironic. I recognize when something is unrealistic, and calling for replays and stoppages is making a pretty hefty demand without much capital to stand on.)

Perich, I loved your ending about kids as a reader and stubbornly optimistic realist. But, erm, I have to ask you something about little league soccer: Are you sure it follows the same time rules as FIFA or professional-level soccer? When I played as a young-un, we had two fifteen-minute halves that were iron-clad. Although, to be fair, we did “go as long as we were allowed,” but in a different sense- we went until the ref blew their whistle for whatever reason, were slaves to the ref’s clock. And, on that note, there were a lot of stoppages when girls got fowled (we did this weird thing, I forget what it’s called, where the “victim” got basically a kickoff from where she was fowled at; or they would take the ball out of bounds and her team got a free-throw back in)- and those had no impact on the time. I’ll admit this could be because of the gender of the league, or it could just be that Las Vegas is rather… odd (conspiracy theory about this, but for somewhere else). Maybe both- a weird league protecting/babying the “fairer sex.”

Which leads nicely to an @Fenzel: “A lot of the structural circumstances around race and gender in America have less to do with contemporary attitudes and more to do with the circumstances from a hundred years ago that still stick with us, because old habits die hard.” I’d also like to piggyback/specify a bit and point out how, as such, there are far more opportunities for girls and women in the U.S. to play what Americans call soccer than what we call football. And the same can be said about baseball, too.

I was also going to bring up the class thing, but from a different angle. American-style football is, indeed, much more expensive- even a football costs a lot more than the kind of ball one could play soccer with (although I disagree with the notion that people don’t play pickup football games without pads, but I will concede it probably happens less often); then you have pads and helmets and such to account (HAH! I’m talking about costs, get it?) for. As such, the conspiracy theorist, anti-classism, pro-proletariat blowhorn in me wouldn’t be surprised if American-style football became a status symbol because of how much playing “properly” (i.e. with the right equipment) would cost. This would also explain why it was selected for promotion by colleges (and high schools) as their premier sport, as a way for the institutions (or counties, districts?) to try to demonstrate they can be “quality” ones- if they can afford *football*, they must be great! So football became the status-quo because the haves made it so, to the point where poor communities invest every last cent they have on their football team because they are led to believe “it’s all they have” or whatever, thereby causing other programs to suffer. I’m not saying no other sport ever gets priority, either- clearly there is an imbalance in how schools are funded across the board, and in myriad ways; and correlation doesn’t mean causation. But still, I wouldn’t be surprised, I wouldn’t be surprised at all.

A couple of thoughts, coming in late to the party.

On the Role of Sports Officials (referees, umpires, etc.):

Their precise role depends on the view of the nature of the Reality of the Game. Does the Game exist as an objective reality, and the officials are there to confirm what really happened, or is it subjective, and we endow the officials with the authority to decide what the ‘official’ reality is? If the latter, then there is no such thing as a blown call – and there cannot be.

One could also consider a “play” as something in a state of quantum indeterminacy, and it is the call of the officials that (so to speak) collapses the wave function of the play (Case in point, the triple play turned by the Mets this past May 19 – the triple play wasn’t confirmed until after a consultation amongst the umpires).

On Instant Replay:

If one believes that the Game exists in an objective reality, instant replay review becomes a useful tool for the officials. But at what point do you stop using it? A baseball game can see literally hundreds of plays (every single pitch is a play!) – do you want to use replay on every single pitch to confirm whether it was a ball or strike?

And why limit replay to just key games, or key plays? There was much ado when umpire Jim Joyce blew a call that cost Tiger’s pitcher Armando Gallaraga a Perfect Game back in May. Since it happened on what would have been the final play of the game, there were calls for the Commissioner to overturn Joyce’s call (which he later admitted he blew). But would there have been the same level of uproar if the blown call happened much earlier in the game?

One needs to apply some sort of Categorical Imperative to the use of replay/review.

But enough Overthinking sports officiating….

One other reason baseball rules: It’s the only major team sport where the shape of the playing field is not a standard, and in ways that affect the play of the game. One soccer field is exactly like another (or at least it’s supposed to be). Hockey rinks, basketball courts, and football gridirons all adhere to unalterable rules of conformity. Baseball has things like Fenway Park’s “Green Monster” that have a clear and direct effect on the play of the game.

@Gab:

I’ve never heard of anyone not on an organized team playing American football WITH pads. Most of the backyard football I’ve encountered has been of the ‘guys get together and throw a ball around’-type. Either two hand touch for downs, or with a friendly understanding to limit the intensity of the hits for tackle downs. So i don’t know if I guy the pads are expensive = rich person’s game.

The sport I saw being used that way was hockey.

@Valatan: Well, I think there’s a significant change in street/pickup v. official football in what you have right there: without pads, the rules change to “two hand touch” and the like. I’ve seen that happen, actually, but hadn’t even thought of it until you mentioned it. So it’s not “proper” football, it’s a (one could say literally) poor imitation of the “real” thing because they aren’t tackling (or at least aren’t tackling as much), it’s not as gridiron, etc. Rules about contact and such that would, indeed, change the way the game is played, don’t really occur in pickup soccer. You’re right, pickup football doesn’t involve pads, and that’s the point. Whereas I’ve seen (and participated in) pickup *soccer* games where some participants had pads before, some of these padded players not even being involved in leagues or anything elsewhere- they just have their own sets of pads and sometimes cleats, too. I wouldn’t know if football cleats are more expensive than soccer ones, but I can’t testify as to whether I’ve seen pickup football players in cleats, too.

I started getting pretty off-topic there, so I’ll stop now, but yeah.

I wrote a long comment that did not get successfully posted so I emailed this to John – in it, I noted that despite their unAmerican nature, Rugby and Cricket both use technology to assess decisions (as does the Anglo-French sport Tennis, but that has popular and successful American influence, so I skipped past it) – only football (aka real football, our football, the footie) has kept away from embracing it. The culprit in this is said to be Sepp Blatter, FIFA President (or President-for-Life, so it seems), who demands that the game remain the same at the highest level as the most basic.

(For more on this, especially the potentially hypocritical influence of sponsorship in a fun way, try Baddiel and Skinner’s podcast, possibly the most popular podcast in the UK, having had a million downloads over the course of 12 20 minute shows on Absolute Radio ).

However, it might just be that Blatter believes in Time’s Arrow more than any American ever could.

Clearly it objected to me linking another podcast.

Oh, one final thing – do they call it overtime when commentating on ‘soccer’ in the USA? Because I would always call it ‘extra time’, and I wondered whether that was just peculiarly British.

Heard an interesting comment (on another podcast) about how some people like soccer partly because it’s like an alternative history of the world, where the US isn’t a superpower, and poorer nations can outshine wealthier ones. Plays into theories of international sport as an outlet for dealing with tensions between nations. Like a junior sized war substitute.

Sorry for the double post, but that last comment was “#comment-19999”

Which means this comment HAS A POWER LEVEL OF 20,000!!

Congrats on the website milestone OTI :)

Thanks, Lara. Just wait till you see the milestone we hit at the end of this coming week. :)

I think that the lack of review can’t really explain soccer’s poor relation’s status in the US, because, as you said, it’s relatively recent to most sports. As others have said, the presence of US-born games can be a big part of the explanation, especially as kids grow up and want to emulate their sports heros, of which there aren’t that many soccer players, because no sponsors have bothered to make much of a deal out of soccer players, because soccer’s not that popular. A vicious cycle, in other words.

Tied to this somewhat is that soccer is NOT a high-scoring game. You can go for over an hour with no score. Unless you know the rules of the game and have an eye to tell what sort of play is happening, that can seem really boring to someone used to a basketball game.

I think a key factor, if you want to get into the US mentality, is that a game can end with a tie in most variations of league play. For the US, the competitive aspect of sports is key. We think of sports as a way to prove how much better we are than other people. Many of our sports movies focus on the little guy overcoming the odds to win. (Except Cool Runnings, but that’s not about the US team, so it’s okay that they don’t win.) We have intense rivalries between teams that require a definitive resolution to “prove” who is superior. With soccer, you can have a tie. What does that say? That both teams are equal? What’s the point, then? How do we prove who is right and who is wrong if there’s not a clear winner?