My introduction to the Elder Scrolls series came with Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind. Set in the Imperial backwater of Vvardenfell, it sets you loose in the internecine squabbles of an island divided between noble Houses and rural tribes. The three god-kings of Vivec, Almalexia and Sotha Sil rule over the island continent, cloistered away in exotic fortresses. You can either explore the island to your heart’s content, gaining treasure and rising in stature among the various factions, or you can pursue the main quest and prevent the return of the imprisoned god Dagoth Ur. In the course of hours of play, you might do all of the above.

Have you seen my god-king's perfectly symmetrical floating city? Sweet, right?

The setting fascinated me: a weird blend of Byzantine decadence, Oriental religion and unique mythology. While plenty of games reveal their world through in-game text (see Deus Ex; see the journal entries in SSI’s “Gold Box” AD&D games), Morrowind‘s books and scrolls were unique. They weren’t just one-radian knockoffs of medieval Western Europe, Tolkien with the serial number scratched out. It was esoteric and challenging. I loved it.

For instance, here’s half of the first Sermon of the Thirty-Six Lessons of Vivec:

He was born in the ash among the Velothi, anon Chimer, before the war with the northern men. Ayem came first to the village of the netchimen, and her shadow was that of Boethiah, who was the Prince of Plots, and things unknown and known would fold themselves around her until they were like stars or the messages of stars. Ayem took a netchiman’s wife and said:

‘I am the Face-Snaked Queen of the Three in One. In you is an image and a seven-syllable spell, AYEM AE SEHTI AE VEHK, which you will repeat to it until mystery comes.’

Then Ayem threw the netchiman’s wife into the ocean water where dreughs took her into castles of glass and coral. They gifted the netchiman’s wife with gills and milk fingers, changing her sex so that she might give birth to the image as an egg. There she stayed for seven or eight months.

Then Seht came to the netchiman’s wife and said:

‘I am the Clockwork King of the Three in One. In you is an egg of my brother-sister, who possesses invisible knowledge of words and swords, which you shall nurture until the Hortator comes.’

And Seht then extended his hands and multitudes of homunculi came forth, each like a glimmering rope through the water, and they raised the netchiman’s wife back to the surface world and set her down on the shoals of Azura’s coast. There she lay for seven or eight more months, caring for the egg-knowledge by whispering to it the Codes of Mephala and the prophecies of Veloth and even the forbidden teachings of Trinimac.

…

And so forth. Folks familiar with Judeo-Christian theosophy might recognize the diction of the Old Testament or Torah. Taking Biblical sentence structure and filling it with unfamiliar words helps expose just how weird the Bible is. The netchiman’s wife whispered the Codes of Mephala to the egg-knowledge gifted to her by Ayem, who changed her sex in a coral palace beneath the sea. Got it.

But that’s not the weirdest part!

Sup.

In the course of playing the main quest of Morrowind, you’ll come face to face with Lord Vivec, locked away in the city that bears his name. When you meet him, he will confirm that you are the Nerevarine, the reincarnation of Nerevar, and the only one who can undo the curse that afflicts the continent of Vvardenfell. But he also confirms something that you’ve probably begun to suspect if you’ve been following the in-game text: that Nerevar was once a companion of Vivec as well as the other gods of Morrowind, Almalexia and Sotha Sil. In fact, Vivec and the rest only became gods after uncovering the Heart of Lorkhan, the artifact that Morrowind‘s final villain, Dagoth Ur, is using to escape from Red Mountain. Prior to that, Vivec, Almalexia and Sotha Sil were councilors to Lord Nerevar, who ruled the island of Vvardenfell as a king.

That in itself is a bit of a twist: that the gods of Vvardenfell, the supreme rulers of Morrowind, were once just ordinary people. They only became gods because of a magical relic that they found in the heart of the earth. It makes the ritual and superstition surrounding Vivec seem a little silly: rather than the mysteries of faith needed to comprehend an immortal creator, it’s just the weird trappings of one guy.

The obvious follow-up question is: if Vivec, Almalexia and Sotha Sil got magical god-powers from this relic, what happened to their buddy Nerevar? Here opinions differ. If you ask Vivec or read what he told his priests, Nerevar suffered a fatal wound in the initial fight against Dagoth Ur. However, a sect of dissident priests within Vivec’s ecclesiarchy believe something different: that the tribunal killed Nerevar because he wouldn’t let them use the Heart of Lorkhan to become gods.

I've been doing push-ups and listening to Slipknot for a THOUSAND YEARS.

Two very different responses. You learn both of them in the course of the main quest. Neither of them changes the outcome, or even the nature of the world. Learning that Vivec was an ordinary guy who might have killed his liege does not smash the priesthood of Vivec in one humiliating blow. But it makes you, the player, regard everything different. Vivec is no longer the sage dispenser of wisdom, giving you the guidance you need to complete your quest and save the world. He’s now a canny manipulator, sending the reincarnation of his onetime king (whom he might have slain) to dispatch his enemy.

Those of you who follow Internet arguments between entrenched political camps will recognize this as historical revisionism. For those of you who lead happier lives: historical revisionism is the act of reinterpreting conventional wisdom surrounding some historical event or figure. Pundits and historians engage in it because people rely on history as a guide for what to do next. Changing the lessons available from history – changing the moral of the fable – can disarm one’s ideological opponents or add more weapons to one’s own arsenal.

To use recent examples from American politics: conservatives have spent years attacking the idea that President Franklin Roosevelt’s “New Deal” helped get the country out of the Great Depression. Some economists, like Harold Cole and Lee Ohanian, have argued that the New Deal actually prolonged the Depression, by diverting capital and labor through inefficient central planners (the CCC, the PWA, the WPA, etc) rather than letting it accrue to where it would be useful. Other historians have argued that the New Deal was a net harm to America because it legitimized near-fascist levels of government control over business.

On the left side of the aisle, historians like Howard Zinn sought to repaint America’s historical record as well. In A People’s History of the United States, Zinn made the case that the story of America was a story of common people, not elite leaders. It’s from Howard Zinn and historians of his school that we get the image of the Founding Fathers as white, male plantation owners. In defending his book from several critical reviews, Zinn wrote:

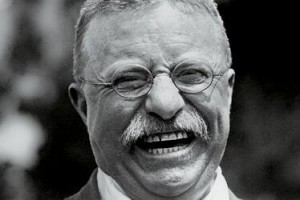

My hero is not Theodore Roosevelt, who loved war and congratulated a general after a massacre of Filipino villagers at the turn of the century, but Mark Twain, who denounced the massacre and satirized imperialism. I want young people to understand that ours is a beautiful country, but it has been taken over by men who have no respect for human rights or constitutional liberties.

I meant 'Bully' as an encouragement, not an imperative.

Note that neither side is making up facts here. Teddy Roosevelt did indeed congratulate Maj. General Leon Wood after the Moro Crater massacre, just as the PWA was an unprecedented level of federal intervention in the American economy. But not every history textbook emphasizes the same facts or draws the same conclusions from them. Historical revisionism is meant to challenge that.

“Either way, by presenting a world with such rich history and giving players extensive option to make their own path in it, Skyrim forces us to reconsider our roles as game players and storytellers.” I think this is why the RPG genre will never go away.

Also, “There is no stopping point: there’s a main quest that you can complete, but the action keeps trucking after you finish. The “game,” if we can still call it that, continues until you set down the controller, just like a manuscript remains stable until you pick the pen back up.” You can work through the many different sub-arcs e.g. assassin and thieves then turn around and do something completely different. Much like some of the long winded prose placed in books scattered through the game, the player can mold Skyrim vis a vis the way Skyrim interacts with them. The game space is a great world to get lost in making.

What I found really interesting was the only people Skyrim portrays as unambiguously evil (besides dragons) are the Thalmor, the elf supremacists who invaded the Empire and made it a client state. One reason we know they are bad guys because the Thalmor claim to have ended the Oblivion Crisis in the elf lands. (Oblivion spoilers:) We know this is wrong because in Oblivion, you and the emperor are personally responsible for ending the crisis across the entire continent. Because the Thalmor are secondary to the main plot, you can’t do anything about this (not that correcting them on a centuries-old historical point would matter much to what is happening in Skyrim).

I haven’t spoken to enough Thalmor in my playthrough yet to get to that point, but that’s interesting! Another good example of historical revisionism. The victors write the history books.

I’d recommend finding and reading Rising Threat, Vol. 1-4; they’re the accounts of an Altmer during the time of the Oblivion Crisis and afterwards during the rise of Thalmor.

Also, slight edit:

“Skyrim sets the clock farther ahead than any of the previous four games. Four hundred years after the events of Oblivion, the Empire is no longer what it once was.”

Skyrim only takes place two hundred years after Oblivion. The Third era ends at 3E 433 (which becomes 4E 0), Skyrim’s events begin in 4E 201.

Yeah, it was 200 in the original draft, but I changed it post-publishing. Don’t know why I was suddenly convinced it was 400.

The thing is, even games that offer choices almost inevitably push you in one direction or another. Assume I’ve decided to play Skyrim as a (for want of a better term) Lawful Good character. When I encounter the Thieves guild or the Dark Brotherhood, I would obviously be disinclined to join. But in that case, I’m going to miss out on two of the half a dozen questlines that make up a major part of the game’s content. At least, in Skyrim, they put in an option that, after you first meet the Dark Brotherhood, you can choose to report it to the authorities, and they’ll send you to kill them all. But a single battle, even with the decent loot you’ll get, is never going to match what you could have gotten out of the questline. And the Thieves Guild doesn’t even allow you that – your choice is between doing the whole questline and not doing any of it. Moreover, once you start a questline, you can’t back out of it or change your mind. The option to tell the authorities about the Dark Brotherhood is no longer open after you decide to join, whether or not you’ve killed anyone for them yet. Thus, the gameplay itself tends to promote one path or another, and if your beliefs, informed by the game world, differ, you can either choose a lesser experience or force yourself to quash your beliefs.

The alternative is also problematic. This is what was done with Stormcloaks vs Imperials, to have the choice essentially mean nothing in terms of gameplay… but gameplay translates into content. I was somewhat surprised to discover that a band of rebels and a professional Imperial army had the exact same tactics and strategy to defeat the other. In order to stop people making decisions based on ‘what will gain them the most xp/loot/interesting missions’, the game makers are forced into making every choice exactly the same… except for the interpretive content. Now this works ok if used occasionally; but imagine if the Dark Brotherhood, the Thieves Guild, the Magic College, the Companions the Bard’s Guild and even the main quest all had alternative questlines that were equal and opposite to them in every particular except for their moral and historical background. It’s going to seem extremely contrived, extremely quickly. Especially since, if you’re making choices, you want them to have consequences you can see and understand – and consequences more subtle and variable than the good ending/evil ending dichotomy you get in games like KotOR.

This is possibly less relevant to the question of historical revisionism, except as you want it to affect the gaming itself. But if it can’t affect the gaming, then you’re basically just being railroaded down a plot, just like before.

But if it can’t affect the gaming, then you’re basically just being railroaded down a plot …

The difference is if the plot is ambiguous enough to force you to consider the story different. Think of Braid, for instance, or Portal. I think that’s an interesting next step in video game design.

That’s true, but I can see a distinction between those games, where the ambiguity is that you cannot be sure what is actually happening at the moment (or why), and Skyrim, where, in the Imperial vs Stormcloak struggle, you’re entirely certain of what’s going. The ambiguity in Skyrim is about history and also your political values. Self-determination vs the order and stability of an imperial government, for instance. Instead of making you ask what is going on and why, you’re asking, should it be going on and is my support of it a good thing.

They are, of course, very different types of games, and the things that suit an RPG would probably be out of place in a puzzle type game (and vice versa). But I do think that RPGs are stuck between having your choices likely being more influenced by gameplay than beliefs, or having contrived plot scenarios where every belief and choice turns out exactly the same.

I completely agree with this train of thought, although I’m also extremely cynical of Skyrim’s choices and storytelling, given how they completely cocked up even the most basic roleplaying elements (For a simple example, in a province so full of racial tension, there isn’t a single point in the game where your choice of race changes anything. It’s one thing to allow the roleplaying to take place in the player’s imagination, but when the player does something that should be acknowledged and isn’t…that’s just poor storytelling/roleplaying).

Argh, tangents!

Anyway, while there are many RPGs that suffer from the problem of gameplay outweighing actual beliefs (ie. KOTOR, where actual roleplaying is punished – you’ll lose force mastery if you don’t pick the blue or red option every time), and many more where your choices have the same outcome (Mass Effect fits this bill – the series has has no meaningful consquences for any of your actions)…I think there might be a couple RPGs that have both meaningful/drastic story consequences *and* allow the player to follow their own beliefs.

The prime example that comes to mind is The Witcher 2…which isn’t much of a surprise, since that series is absolutely determined to revolutionise the way players think about decisions. The game features a malleable protagonist – one with a set role in the game (that of Geralt of Rivia, professional monster hunter), but whose motives are entirely flexible. Through dialogue and actions, the player fleshes out what it is that Geralt desires (be it revenge, the secrets of his past, his long-lost love, etc), and what he shall pursue during the course of the story. These choices are not hugely influenced by the gameplay (they will often only have far reaching consequences, unknown to the player at the time), nor are they purely interpretive (other characters will question your motives based on earlier decisions, even those the player made in the previous game), nor do they railroad you towards the same outcome (the entire second chapter is vastly different depending on your decisions in the first chapter – different towns, different plot threads, different quests and battles, etc).

So it seems as if The Witcher 2 is…ugh, I don’t want to use a cliche like ‘the finest example of choice-based storytelling at present’, since it isn’t perfect. What it does offer is a wondeful blend of all of the above modes, and it does them really, really well. It’s one of the few games I’ve ever played where players have vehemently argued over the story decisions they have made, both sides firmly believing that their decision was not only absolutely right, but the obvious choice to make in that situation (“he’s a terrorist!” “he’s a freedom fighter!”)…and that’s a wonderful thing indeed for these sorts of games.

The Deus Ex series has been good at providing different narrative outcomes if you align with different factions. (I still need to play the newest one; it’s on my shelf)

On a side note;

While I sadly haven’t had time to read it I can think of at least one novel that casts Sauron in a similarly positive light (a link to the full English translation is available at the bottom of the Wikipedia page).

(I was going to write something about the implicit, arguably reactionary ideological underpinnings of the traditional Fantasy world from Tolkien and onwards, and various parodies of and, other reactions within the genre against this, but I realise others have probably written about this before and better, so I’ll just leave the link as a hopefully amusing example).

Although there seems to be one important difference between The Last Ringbearer and the Elder Scrolls series (or what I can gather from this article, not having played any of the games) that I suppose I ought to emphasise.

While The Last Ringbearer appears to be modern and epistemically unproblematic, merely replacing one True Account of life in Middle Earth with another (significantly, Tolkien’s nostalgic, negative account of modernity and modern technology with one more positive), the Elder Scrolls series seems more postmodern and epistemically problematic in how it merely offers different, irreconcilable accounts of historical events, without providing any authoritative answer as to which is the correct one.

(I seem to have problem posting again, so I’m reposting this. As usual, if this is a double post, please delete it)

Although there seems to be one important difference between The Last Ringbearer and the Elder Scrolls series (or what I can gather from this article, not having played any of the games) that I suppose I ought to emphasise.

While The Last Ringbearer appears to be modern and epistemically unproblematic, merely replacing one True Account of life in Middle Earth with another (significantly, Tolkien’s nostalgic, negative account of modernity and modern technology with one more positive), the Elder Scrolls series seems more postmodern and epistemically problematic in how it merely offers different, irreconcilable accounts of historical events, without providing any authoritative answer as to which is the correct one.

(apparently I have problems posting again, as usual, if this is a double post, please delete it)

Although there seems to be one important difference between The Last Ringbearer and the Elder Scrolls series (or what I can gather from this article, not having played any of the games) that I suppose I ought to emphasise.

While The Last Ringbearer appears to be modern and epistemically unproblematic, merely replacing one True Account of life in Middle Earth with another (significantly, Tolkien’s nostalgic, negative account of modernity and modern technology with one more positive), the Elder Scrolls series seems more postmodern and epistemically problematic in how it merely offers different, irreconcilable accounts of historical events, without providing any authoritative answer as to which is the correct one.

Damn, I triple posted. Now this is downright silly!

I’ll add my endorsement to The Last Ringbearer. It’s a very fun read, and some of the tangents he explores are incredible (the Empire of Harad, the espionage in Umbar, etc.).

I’ll only do it once, though, not twice or three times [a lady…]