Enjoy this Guest Post from frequent contributor Sean Nixon! – Ed.

(Disclaimer: The opinions of the heroes as depicted in this article are largely guesswork and shouldn’t be taken as spoilers.)

Iron Man vs Captain America, red vs blue, cats vs dogs, us vs them. At the center of advertising for Captain America: Civil War rests the promise of a five on six drag out brawl between Team Cap and Team Iron Man. This in itself is nothing especially novel. The second act of any big crossover event tends to culminate in an excuse for the heroes to demonstrate their commensurate strength via punching, shooting, witty quips, etc. Up on the big screen, Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice and Avengers both let their titans duke it out amongst themselves until the real threat arrived. In contrast, the original Marvel comic crossover storyline Civil War never made it out of act II. There’s no unifying threat and instead of a plot that’s an excuse for a superhero show match, the battles are there to give physical form to the philosophical debate the writers are interested in exploring. In keeping with the best of its predecessors (like the surprisingly similar in premise Kingdom Come) the stakes are hearts and minds.

The references to Team Cap/Team Iron Man and the titular battle shot from the promotional material both invoke the image of superhero fighting as a sport. Two fairly balanced well delineated teams, a sparse playing field, and colorful mascots all help to cast this year’s Marvel blockbuster as an fun day at the ballpark. In a way, this is true. The Marvel cinematic universe has a strong track record of delivering on their promise of an entertaining superpowered romp, teeming with feats of physical acumen. However, where a sports team competes for pride, glory, and maybe a bigger paycheck, the heroes in Civil War compete to define the ethical balance of security and freedom. Unlike alien armies or power mad billionaires who are merely out to rule the world, these stakes potentially seep out into the nonfiction world.

The conflict in Civil War revolves around the Superhero Registration Act (the Sokovia Accords in the film), a law which essentially drafts all superpowered individuals (hero or villain) into government service and divides the Marvel universe into those who are pro-registration, lead by Iron Man, and those who are anti-registration, lead by Captain America. While this clean division makes for captivating splash pages, it whitewashes the complexities inherent in any political debate. The full story, which takes place across the pages of over fifty comics, delves deeply into issues of privacy, surveillance, authoritarianism, the war on terror, and post-9/11 America. Captain America: Civil War can’t hope to cover the same breadth of material in a couple hours, but it also doesn’t have to juggle the cast of Marvel Comics’ 77 years of continuity. Instead, the twelve character cast gives us a scope that one can more reasonably wrap their mind around. To this end, I’ve put together a few models that try and illustrate the way government regulation of superheroics, depicted as a black and white issue, really has a lot more grey involved.

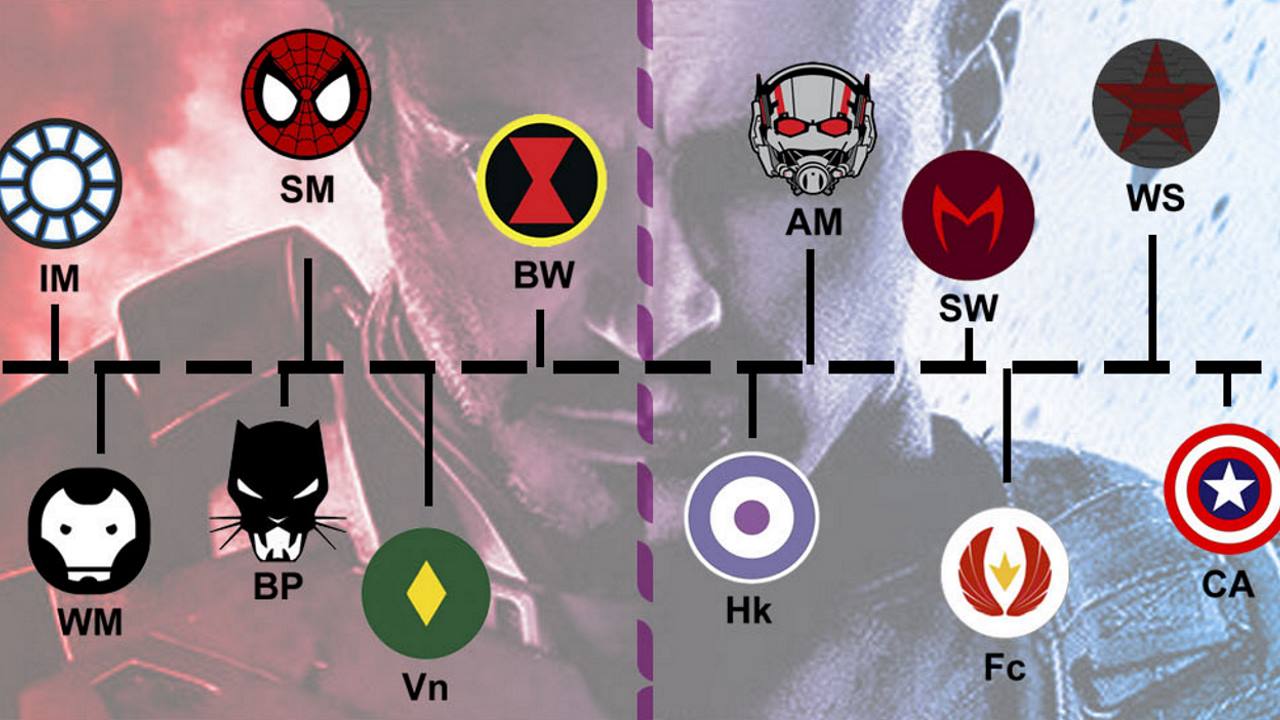

If everyone could just skoosh in a little, some of you aren’t in the shot.

One thing that’s constant across all the models is the “super-delegates.” Super politics effectively operate like an oligarchy, where the only people who get a vote are those that can back it up with superpowers, hereafter called super-delegates. For the sake of my sanity, I’m going to leave it at one super-delegate one vote, though an argument could be made that say Vision’s vote counts for more than Hawkeye’s based on combat effectiveness in the electoral super-math. The demographics of the super-delegates, in order of first appearance in the MCU, are

- Iron Man (IM): Comes from money, tech industry billionaire, former civilian hostage, traditionally liberal.

- War Machine (WM): Close ties to Iron Man, career soldier.

- Black Widow (BW): Russian defector, government official.

- Hawkeye (Hk): Family man, retired.

- Captain America (CA): Career soldier, prominent figure in previous administration, traditionally conservative.

- Winter Soldier (WS): Soldier turned mercenary.

- Falcon (Fc): Close ties to Captain America, veteran working in the VA.

- Scarlet Witch (SW): Foreign national, strong anti-Iron Man leanings.

- Vision (Vn): Sentient computer…?

- Ant-man (AM): Ex-con, family man, well educated.

- Black Panther (BP): Foreign royalty.

- Spider-man (SM): Teenager, tough on crime.

With these as the core components, the question becomes how to understand the way each super-delegate decides their vote.

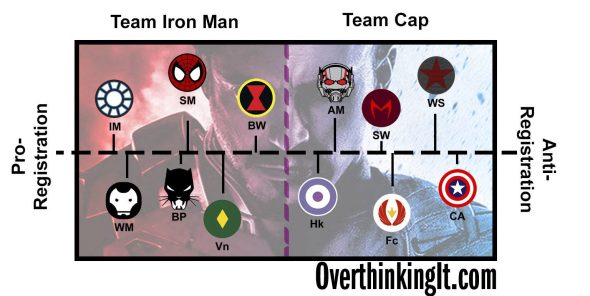

Model 1: Us vs Them

Basically, Model 1 reflects the marketing and propaganda surrounding Captain America: Civil War. There are simply two categories, and each super-delegate belongs to one or the other. The primary virtue of this model rests in its simplicity. It does technically model the situation (though rather poorly), and it establishes a base from which to build more useful models. There are 12 icons, representing the 12 super-delegates, a red region representing the pro-regulation party and a blue region representing the anti-registration party. This model promotes an adversarial view of politics that leads to polarization and gridlock (\end soapboxing). Though there’s certainly a danger to judging a model on moral grounds, this model also fails to explain the phenomena of side switching which occurs in the comics (and most likely in the film). Thus, there’s room for improvement.

Model 2: Super Spectrum

The first real model arises from adding one new feature to Model 1: the super-delegates’ opinions varying levels of conviction. In other words, this model reflects the reality that there is a spectrum of possible stances on superhero registration, not just two. Captain America may be staunchly against registration, but Ant-Man would be fine with it once they add dental for dependents. Black Widow may be willing to accept registration out of necessity, but Black Panther came all the way from Africa to make sure it got enforced and intercontinental flight aren’t cheap. A general depiction of Model 2 would look something like this…

The center of the opinion axis represents complete ambivalence and the farther to the left or right of the center the stronger super-delegate’s conviction for or against regulation, respectively. In this model, it’s clear that the characters near the center, like Black Widow and Ant-Man, are closer in position to each other than they are to the figureheads for their respective parties.

Model 2 allows for a couple possible explanations for a super-delegate changing sides. The more simple explanation involves a character near the center wavering in their opinion and slipping over the cutoff point to the other side. In contrast to Model 1, this sort of jump seems more plausible since it requires only a small shift in position. For example, say the only reason that only reason Hawkeye has decided to go against registration is the overuse of commas in the document, but then on reconsideration decides they were in fact necessary to keep the language clear. Boom, suddenly you’ve got a turn coat. (Please, let that be in the movie!)

The other explanation concerns how the dividing line gets drawn. Thought of as an election between Tony Stark (Iron Man) and Steve Rogers (Captain America), as opposed to an issue ballot, the dividing line can be thought of as the midpoint between their respective platforms. In this case, if Tony agrees to add paid family leave to his registration act, then this moves his position towards the center and as a consequence may pickup a moderate super-delegate from the anti-registration party. Or, Steve might agree to let U.N. inspectors audit the actions of the Avengers and move his own position towards the center. Taken to its logical conclusion, these attempts by Tony and Steve to pick up more supporters by moderating their viewpoints results in a “race to the center”. This sort of thing happens in the real world as politician move from primary elections into the general, however, it suggests that the end result should be a fair compromise. There’s a decent chance that the formation of a coalition Avengers occurs to fight a common foe for the cinematic adaptation. However, in the comic, no middle ground can be found. Captain America and his Secret Avengers win the physical battle, but lose the moral high ground and for a time the SHRA/Sokovia Accords becomes the law of the land. Again, there’s still room for improvement in the model.

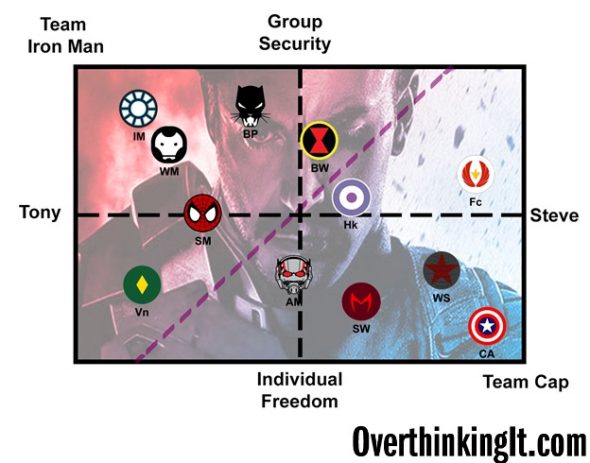

Model 3: Principle vs Personality

Model 3 takes the idea of political positions that exist along a spectrum and moves it into higher dimensions. Instead of considering each super-delegate’s position on registration directly, we can look at some of the underlying beliefs and opinions that influence how they end up choosing side. For an easy example, imagine two axes: one axis ranging over the spectrum of positions on group security vs individual freedom and the other considering each super-delegate’s personal opinion on Tony vs Steve. Where before there was a single cut off point dividing the parties, there’s now a diagonal line cutting the plane of possible positions in half. Thus, some one like Black Widow who has closer ties to Steve still ends up on team Iron Man due to her stance on security. Likewise, some one like Vision who favors individual freedom can end up on pro-registration side based on his loyalty to Tony.

In Model 3 the “race to the middle” no longer occurs, Iron Man may be able to soften his hardline stance on security, but he can’t change where he sits on the Tony vs. Steve axis. For every supporter Steve picks up by compromising with the U.N., he risks losing one that rests in the quadrant which strongly defends civil liberties but also has a history with Tony. If Captain America isn’t wholeheartedly championing their cause, they might as well stand with their friend. In the example diagram, if Tony and Steve completely switch position on registration (shifting their respective icons and rotating the purple dividing line 90 degrees), then there’s still a 6/6 split with each losing two supporters for the two they’ve gained. An interesting addition in the two dimensional model is the possibility of having super-delegates on the same team with nearly opposite viewpoints, like Black Widow and Vision. Model 3, while successfully predicting side switching without a race to the center, opens up the doors for other additions. What other opinions play a role in deciding to be Pro/Anti-registration? Position on gun control? Position on NSA surveillance? Position on tax code? International trade? Foreign aid? Gay rights? The NIH?

N-dimensional Politics

This now takes the story to MIT and the 1966 summer vision project. As the urban legend goes, the task of hooking a camera up to a computer to recognize objects was handed off to some undergraduate researchers to knock out in a couple months. As expected the task of getting the computer to read in the pixels was fairly straightforward, however the professors running the project greatly underestimated the complexities involved in processing the data afterwards. The process seems simple enough, but consider something like telling the difference between cats and dogs.

This is a cat:

And, this is a dog:

For the glory of Thanos.

Making the distinction happens without any sort of conscious thought, but the mental machinery underlying it is extremely complex. To begin with, the majority of these images are just useless information as far as cat/dog classification is concerned. Really only the outline of the nose and ears are important. If you want to isolate the ears and nose you need to isolate the head. If you want to isolate the head you need to isolate what part of the object is the animal and which part of the image is not the animal. If you want to isolate the animal from the back ground you need to need to tell the difference between the sharp change in color from black to green which indicates the transition from dog to background and the sharp change in color from black to white which just indicates a change in fur color. And, this assumes that computer vision should even follows this chain of logic.

The idea here is that the classification of high dimensional data relies on information from a relatively low dimensional manifold. For a really simple example, the New York City marathon takes place in our good old three dimensional world, but the path of the race is a one dimensional manifold. So, each racer could have information about latitude, longitude and altitude (for 3 dimensions), or just one piece of information giving their distance traveled so far (for the 1 dimensional manifold). Back in the classification of cats and dog, an HD image (which at this point is fairly low resolution) has 2.1 million pixels and each pixel contains three pieces of color information (red, green, blue). That makes HD pictures a 6 million dimensional space. A decent description of the nose and ears requires takes maybe 10-100 pieces of information. Singular value decomposition (SVD) and other methods employed in going from high dimensional data to low dimensional manifolds are a little beyond the scope of this article. Suffice to say, the general procedure involves less teaching the computer about cats and dogs and more giving the computer a bunch of examples and letting the computer figure out the difference on its own.

It’s the same basic problem as classifying a super-delegate into pro-registration and anti-registration parties. Each super delegate has a huge collection of core beliefs and biases and predispositions they’ve developed over a lifetime. Then you project those down onto a manageable low dimensional manifold of more high level concepts, like opinions on relevant issues. Assuming super-delegates are at least as complicated as a cat picture, Model 3 doesn’t even use as much information as you’d need to classify an image as cat or dog. Superheros are complex dictators and we’ve only just scratched the surface.

The Importance of Super-Politics

As discussed earlier, the small (relative to the comic event, or god forbid real world issues) cast of important players in the superhero registration debate give an example where the trees can be thoroughly studied without getting lost in the forest. The other feature making registration such a wonderful case study is its level of disconnect from the real world. The audience comes into Captain America: Civil War without any skin in the game. No one stands to gain millions in super-prison contracts from the passing of the Sokovia Accords. No one has a distrust for superheros because they grew up in a part of the country where that sort of thing was frowned upon. No one is going to get into a row at the thanksgiving dinner table for having a different opinion on the matter. If you try to do a similar sort of deconstruction on climate change the analysis gets lost in the larger debate. It’s about the reader bias on the issue. It’s about the author’s position on climate change. It’s about the publisher’s political leanings. Addressing this in a Science Fiction/Fantasy setting instead avoids those prejudices.

Captain America: Civil War represents a chance to reflect on the way society divides itself into clans and the ensuing escalation of hostilities. The film only gets two hours to make the point and most of that’s gotta be devoted to witty quips, multi-million dollar action scenes, thinly veiled references to american politics and set up for the next five Marvel Cinematic Universe installments. So, when you’re done chatting about how Marvel nailed the characterization of Spider-Man (presumably), give a moment to contemplate (?). Don’t be team Tony. Don’t be team Cap. Be Team Act 3, where everyone bands together to fight space leviathans.

Lol.

I just watched the movie. It has the same problems that Bat vs Sup but with a different tone

A tone that makes all the serious parts completely awkward to me.

I guess is a step in the direction I like (more serious) but is not there yet…

The action though, Jesus christ…

“some one like Vision who favors individual freedom”

Vision says to Cap that it’s for the “greater good”. He supports what the majority supports. Unless he flip flops by saying something else?

Yeah. I wrote this without watching the movie. The particulars of where I placed them were an amalgam of guess work, reading my spoilers, and considering his personality from the comic. The original vision was dead during the Civio War comic, but the person holding the Vision mantle at the time sided with Cap. Also, someone needed to be an example for that quadrant of the graph. Since all I knew about Vision in the film was his little interaction with Ultron on the sanctity of life and the importance of letting it fail on its own, I placed him in the late liberal half of the political plane.

I don’t think getting those sorts of food me details changes the broader point. It’s more like, if we assume Vision is pro individual freedom but has a deep loyalty to Tony, what does that mean. But, I’m happy to hear if you have any other characters you’d like to move around

Having seen the film, I might arrange Model 3 more like this.

(FYI – I edited the comment so that the image is now embedded).