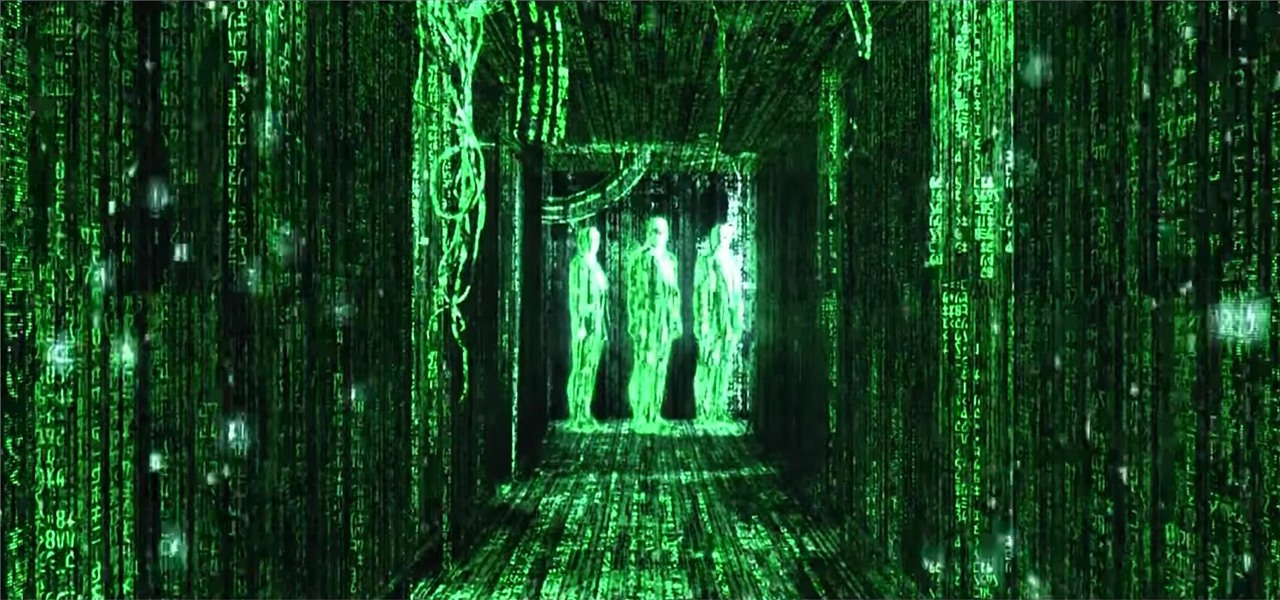

This week marked the 10th anniversary of the sci-fi sleeper blockbuster, The Matrix. It’s hard to imagine, but there was a period in American culture when no one had heard of the Wachowski Brothers, Hugo Weaving or Propellerheads. Keanu Reeves and Lawrence Fishburne re-ignited their careers, playing freedom fighters armed with gravity-defying kung fu and submachine guns, locked in eternal war in a digital prison.

Audiences flocked to theaters for the blistering action, the revolutionary visual effects, the throbbing techno soundtrack and the wirework. But critics picked up The Matrix for another reason entirely – its throwaway references to classical philosophy.

Philosophy professors and hyper-literate college students (OTI’s target demographics) claimed that The Matrix showed clear influences from:

- Plato’s allegory of the cave

- Descartes’ Meditations (the whole “how do I know what I sense is real?” thing)

- Buddhist notions of mindfulness (e.g., “there is no spoon”)

- Calvinist doctrines of determinism vs. free will (“this fate crap”)

The Matrix‘s immense popularity made it a common touchstone for dorm room bull-sessions over the next few years. But what’s even more amazing is that The Matrix actually inspired a few college courses in that time. Courses you could take for credit – at Mississippi State University, at the University of Washington and several others. You could actually get class credit at accredited universities by watching the sophomore effort of the directors of lesbian crime thriller Bound and talking about it.

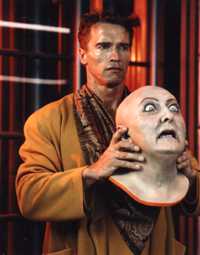

If the above tone hasn’t made it clear, your correspondent remains skeptical about the actual philosophical content of The Matrix. Sure, there’s some talk about determinism and identity and whether we know The Real is The Real. But Total Recall has all of that as well, and the Ivy League has yet to add Paul Verhoeven to the curriculum. It seems clear, to a mildly critical audience, that the philosophy of The Matrix is a thematic flourish, not a hidden message.

Your correspondent could be wrong, of course. It’s entirely possible that The Matrix is a rigorously constructed, meticulously researched compendium of centuries of philosophical tradition, spanning both Eastern and Western schools of thought, translated into a Campbellian heroic journey. Were that the case, then any additional movies set in the same universe would have an equally rich philosophy.

Hm? What now? You’re saying there were sequels to The Matrix? Well, what gems did these expeditions yield?

The Matrix Reloaded

The Matrix Reloaded has, at best, one philosophical underpinning: the notion of reincarnation. Neo (Keanu Reeves) discovers that he is not The One but, at best, The Seventh – a persistent re-iteration in the Matrix’s programming. His role is to oversee the destruction of the human species and then begin their reconstruction, perpetuating the human/machine symbiosis. Neo learns this in a conversation with the Architect, who confronts him with images of his past lives.

The Matrix contains elements of both Plato and Siddhartha, and both of these thinkers believed in reincarnation. So this is a plausible inclusion. However, all this talk of reincarnation comes at the absolute tail end of the film. The preceding 120 minutes offer nothing but a series of water-treading setpieces – a flatly computer-animated brawl, a self-indulgent rant by a French caricature, and a not-bad car chase.

The Matrix Revolutions

The Wachowski Brothers abandoned all pretense at depth when penning the third installment in the trilogy. The Oracle, voice of depth and exposition, gets some vague and meaningless speeches which don’t really drive the plot forward. The humans valiantly fight against the forces of the Machine army – until they don’t, and then everyone’s cool again. And in the end, human fodder and Machine jailer live together in an apparent peace.

For proof that the (supposedly) rich philosophy of The Matrix was abandoned by the time of The Matrix Revolutions, consider the following:

- If The Matrix is about free will vs. determinism, then what does Neo’s decision to be assimilated by the planetful of Agent Smiths mean? Does Neo become “The Source” – the entity which deterministically governs the lives of an entire planet? Or, if Neo destroyed “The Source” and gave everyone free will, then what of the implication (made by the Architect at the end of the movie) that the Oracle engineered the whole thing?

- If The Matrix is about the real vs. the unreal, then what do we make of the ending of the film? Are the humans who were used as batteries to power The Matrix to be left in their ignorant dream? Or were they freed into an apocalyptic world of ashen nightmare? Or did they all die when Agent Smith (who had apparently possessed all of them) disintegrated in that final battle? And if the Machines were the creators of the unreal, then is it a good thing that the human race allied with them in the end, or a bad thing?

The REAL Philosophy of The Matrix

The actual philosophy espoused by The Matrix is that humans don’t know a lot about how the mind and the universe work. Over the last few centuries, we’ve made a lot of crazy guesses. If some of those guesses turned out to be true, and they were put in place by robots, and we got to fight them with machine guns and PVC pants, that’d be awesome.

That’s a great pitch, and we’re all glad the Wachowski Brothers made it happen. But that’s not philosophy, any more than the Jedi Code was a philosophy. It was a philosophical gloss, a sheen of mysticism that transformed what would have been a staid tale of hackers shooting cops into an epic battle of The Underdog against The System. That in itself is remarkable. That’s what good art has always done, from The Iliad through Snow Crash. But art is art, and philosophy is philosophy, and one does not usually advance the other.

With that put to rest, our only question is: what happened to those students who took “Philosophy of The Matrix” courses? Do they still get to keep their credits, even in light of the shoddiness of the sequels? Do they get their diplomas revoked? Do they have to take a summer class on “Star Trek and Man’s Search for Meaning” to catch up?

In terms of philosophical thought, the first Matrix film is clearly modelling itself around Baudrillard’s post-modern philosophies (yes – the Simulacra and Simulation.) However on it’s own the first movie is remarkably not post-modern.

Throughout the first movie there is a clear meta-narrative – humans good, machines bad – that is diametrically opposed to po-mo philosophy.

Yes, the sequels are awful films compared to the first, but they add greatly to the philosophical content by deconstructing the first movie’s metanarrative. By the end of the third movie we have no clear good or bad, right or wrong. Everything is just a matter of viewpoint or experience, a truly po-mo philosophy.

Add to this the philosophic ideas and religious imagery taken from almost every source conceivable, the Matrix is a great movie to study for post-modern student philosophers.

Jon: what does it say of postmodernism that it can’t be distinguished from “completely abandoning the philosophical thrust of the original”?

“Yes, the sequels are awful films compared to the first, but they add greatly to the philosophical content by deconstructing the first movie’s metanarrative.”

Which at least somewhat reinforces the idea of art and philosophy not reinforcing each other, no? See also the entire corpus of Ayn Rand.

@Everyone above: I haven’t seen the Matrix films since they came out, and I don’t plan on watching them again, but I completely disagree that the sequels did away with meta-narrative. In the last movie, Neo dies for our sins! And that fixes everything! Clearly, the last Matrix movie not only continues the meta-narrative of Good versus Evil, but then tacks on the meta-narrative of Jesus Christ Superstar (also known as The Greatest Story Ever Told).

@Perich’s article: I also disagree that Star Trek would make a bad college course. I mean, the stuff with the holodeck alone is rife with issues of space, the real and the unreal, the simulacra and the simulation, etc etc etc. And the political philosophy in Deep Space Nine is pretty complex, at least until the Dominion shows up with their black hats and twirly mustaches.

@My above comment: On second thought, despite it’s awesomeness, a Star Trek course would probably be silly and run out of material by the third week.

ahhhh take that apostrophe out of my final “it’s” in my comment. noooooo my credibility as a teacher and a writer is gone! gone! Gonnnnnne

@perich: That could be argued as what deconstructionism is :)

@Dan: Or possibly just that bad art can enforce philosophical thought?

@Mlawski: I do not see this as meta-narrative, just simple sacrifice. His sacrifice resulted in both sides seeing that they can work together and need each other equally. This is different from saying that he is messianic. However, the borrowing of Christian imagery and adaptation into a new format is clearly post-modern, along with the other imagery from Hindu philosophy and other sources.

@Jon Edmondson: Don’t want to belabor the point too much, but I remember Neo dying in a blaze of light that looked so much like a cross that I laughed out loud. And his girlfriend is named “Trinity.” And there’s a Nebuchadnezzar, too, isn’t there?

Well, if you don’t believe me about the Christian meta-text, listen to this dude, a priest who claims swallowing the red pill is akin to taking Communion: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pn9cuKhSkqw

I get your point that the Wachowski’s borrowed symbols from various sources, but the parallels to the Christian Bible seems to me to be the most overt, especially in the last movie.

@Mlawski: I agree entirely that there are clear and obvious Christian themes. My point, though, is that the Wachowski Brothers are not trying to weave Christian themes with Hindu themes with Buddhist themes into an artful allegorical tapestry. They are throwing them onto a wall by the shovelful and seeing what sticks.

The proof of that (in my eyes) is the mess that the 2nd and 3rd films became.

@Perich: Agreed :)

@Christian themes: I too remember almost spitting my pepsi all over the head of the guy sitting in front of me when I saw that giant glowy cross. Not sure exactly what it does to the metanarrative, though… By the time you see that image, the trilogy’s ideology has been flailing all over the place for about four hours. Then they suddenly pound you with this ridiculously overpowering “NEO IS JESUS.” It certainly *clarifies* the subtext, but it also kind of burns it down and sows the ground with salt.

@Perich: But that assumes that the point of textual exegesis (which fittingly enough started with interpreting the Bible) is to discern the author’s intent. There’s a lot of really smart people who have written about interpreting a text (or film) is an exercise in futility if it’s simply a matter of trying to guess the author’s intention.

I haven’t watched the Matrix movies in a long time, but I always thought that the overriding philosophy was Christian. Nero is the “One”. He brings people back from the dead. He dies himself and comes back to life. He fights demons and clashes with the devil.

I always interpreted it as a pseudo-religous film.

By “Campbellian heroic journey,” you mean “Army of Darkness,” right?

Oh, c’mon, Mlwaski, let’s overthink. I’m sure it wouldn’t be too difficult to come up with a semester’s worth of material for a class about _Star Trek_. From a philosophical perspective, one could base an entire class on just the main commanders/captains and figuring out what schools of thought they represent and comparing and what-have-you. Gender roles? Hellz to the yeah. And politics: Starfleet v. Clingons v. Borg… It’s ripe with fodder for those novelty classes everybody wants to take but don’t get the chance to- like underwater basketweaving.*

And, in fact, leave it to Berkeley to have a course called “Ethics and Star Trek” (although I’d love to sit in myriad of the courses listed here):

http://decal.org/879

*Having graduated from a small college, I never even had the opportunity to take underwater basketweaving. The most “novel” course I took was “Going to Hell,” a study on Christian/ Western v. Buddhist/ Eastern myths of katabasis.

Whoops. Wrong link, and wrong course title. It’s “The Ethics of Star Trek” and this link is the list of all of them:

http://decal.org/courses/index.php

@Gab: Just watched DS9’s Children of Time. Basic plot: The cast goes through an anomaly (as usual) before landing on a mysterious planet. Then they find out they’ve traveled 200 years into the future, and the planet is populated by their descendants. Apparently 200 years ago (a couple of days after the beginning of the episode) they crash landed on the planet and started a civilization. Oh, and Major Kira died from being electrocuted during the anomaly.

The episode comes down to this choice. Either the crew allows themselves to crash land and create this future (leading to Kira’s death), or they go home, thus saving themselves and Kira, but killing their 8000 descendants.

Discuss, in a 8-10 page paper, the ethics governing this choice. Cite your sources.

But we’re going off topic here. So…. the Matrix…

I actually think the Matrix Trilogy, as a whole, appears to take in religious themes, but actually challenges them.

The machines are clearly portrayed as evil within the film, representing the Devil. They keep the humans trapped within a make-believe world until they die and are subsequently eaten. So then, if the matrix represents the known world, then the “real world” (within the film) is representative of Heaven. Heaven here contrasts to the traditional imagery of a place of clouds and happiness that exist as an addition to the world – instead Heaven and Hell exist in the same universe that encompasses the world (or the matrix, in this case). Heaven simply means a higher plane of existance, at least for purposes of this. The humans that are freed sort of represent angels, in that they are able to roam “Heaven” but also occasionally visit “Earth” (the matrix) where they have supernatural powers (biblically portrayed as glowing and flying, here portrayed as kick-ass kung fu moves and the ability to jump really far) with Neo possibly being Jesus, as many others have already pointed out.

So the Devil is keeping humans trapped in the world, so it can pick them out to be eaten. The angels can free a few people, but not many, and are waging war with the Devil to ensure the freedom of the people to come to heaven. Jesus comes and sacrifices himself to provide a truce between the angels and the Devil, in which the angels are allowed to bring more people to Heaven (here it is shown as people who want to be freed, as opposed to the classic “good people go to Heaven, bad people don’t” thing).

Also, just to tie everything up, the Architect is obviously God, as he created the world/matrix.

So far it seems like a fairly obvious interpretation of Christianity. But when you take in to account that it was the humans that created the machines to begin with, then all of that goes out of the window.

Humans create the Devil. The Devil starts killing humans and generally being devilish. The Devil becomes more powerful than the humans and starts to capture them, put them in pods on farms etc. One human creates the matrix as a make-believe world in which the humans can live without being aware, and therefore afraid, of the Devil. This man has therefore become God. He has created the world that the humans believe is real, and therefore the “real world” becomes Heaven (again, Heaven=Hell=Heaven) and the “free people” become angels.

So if the story tells us that man has created the Devil and subsequently created God, Heaven/Hell and angels, does this not make it a challenge to Christianity as opposed to embracing it? Does it not suggest that the entire concept of religion has been completely invented by man? It takes a bit of digging, but that appears to be the message within the story.

Also this was just based on the Christian themes displayed in the film. The other religious imagery within the film has already been pointed out – I don’t know if they can be boiled down to the same message or not, I just went for the most obvious one. It seems a whole new post could be done just on the religious aspects of the matrix and whether they are challenged or embraced within the film.

I really want to take that university course now.

For me, the first movie implied the Buddhist concept of becoming awakened to true reality. As in when Neo came to in the vat.

I found the series to have something in common with The Invisibles comic book series by Grant Morrison. It begins with this clear Us vs Them and then breaks down these walls. In the end the world really isn’t saved, it is ended.

However, the comic is much more entertaining.

@ Dr. Mlwaski: It’s pretty obvious that while the main sources would be Kant and Bentham/Mill, the thesis would more be my own personal opinion rather than any substantial, factual argument. Sure, I suppose one could throw in some Arendt and Berlin for good measure, and maybe even some Ignatieff, but really, it all comes down to my own personal ethics and morality. Could I do option two, instead?

In all seriousness, the only one I saw multiple times was the first, and the others I only saw when in theaters. But I did feel like there was a swing in the Christian direction as they progressed. The first one seemed much more new-age, hippie, pseudo-Buddhist, and in a rather superficial way. I felt it was doing the “there is no spoon” stuff to be cool, trendy, awesome, etc., not because it was actually trying to make a point about how there is no spoon- it had other things in mind, but hold the phone, not until later will we find out. And then the second one happens with its pseudo-pagan orgy rituals and more Eastern-esque influence, so again, more trendiness. But there are more hints at more blatant Christianity in this one that lead into the next. And then the third movie hits you over the head with a huge Sledgehammer of Christianity, and, in a sense, tells you all the other stuff was bad and wrong because look, Neo=Christ and that’s Good because He has just saved everybody, just like the REAL Christ! Perhaps I’m taking it too far, but I saw it as Christian propaganda, if you look at the trilogy as a whole, and as the triumph of Christianity over other, “uncivilized” cultures. Imperialist/Orientalist, something like that.

I agree. The “there is no spoon” thing has nothing to do with buddhism. At least after a period of time spent in the so-called “mystical” period I think all buddhist go through. There is nothing mystical about buddhism or anything else. You finally come to that understanding. But the experience of becoming awakened is bizarre beyond belief. When you experience it, it seems to be something that has no cognitive context to place it with. But, in the end, it’s just another state of consciousness. And all states of consciousness are special. The present moment is fine beyond belief.

I was just wondering, in so far as the Christian allegories can be applied. If Neo is Jesus, the Architect God etc etc. What does Smith represent? He begins as an agent of the matrix promoting control and conformity and ends it as a virus taking over the entire matrix. I can only presume as to what his plan would of been if it was allowed to play out but could we have seen humanity eventually waking up in the pods with Smith imprints as seen in the sequels. Was Smith, allegorically speaking, a plague or maybe a cleansing flood. With humanity and presumably eventually the machines all an extension of Smith wouldn’t the world be given, essentially, a reboot. Sure they’ve all got smiths personality to start with but that would evolve based on circumstances and the bodies he’s placed in. So is he Noah or the Antichrist?

My main problem with the second two Matrix movies is: why, oh why, does it never occur to anyone to question how they know they’re really, really out of the Matrix? C’mon people – I can remember at least two Star Trek TNG stories which hinged around people thinking they had left a simulation, but actually just were tricked into thinking they had left the simulation.

I was 90% convinced this is where the third movie was going. At the end of Reloaded, Neo discovers he has the ability to fry sentinels in the real world. How? Oh, I thought, he’s not IN the real world. Interesting twist.

That works out well, because the Matrix series had really painted itself into a corner. You’ve got billions of humans in vats – can you really take care of them on a planet with no sunlight? There CANNOT be a satisfying ending to the Matrix trilogy. In fact, it’s not even clear what the humans’ goal is. To destroy all the machines? But then billions of people would die. I guess it’s just to protect Zion, while freeing people from The Matrix one at a time. And you know what? Lame.

So what I thought Revolutions was going to be about is Neo realizing he’s still in The Matrix, and trying to become the first person to get out for REAL. And then at the end, it turns out the real real world is a little less bleak than the pretend real world (there’s still a sky).

Hey, can anyone explain to me how Neo blows up all those sentinels? Anyone? Bueller?

Though I think the analysis could go much deeper, I thought some of your points were well-thought out.

However, I felt an almost allergic reaction when I read this:

“But art is art, and philosophy is philosophy, and one does not usually advance the other.”

If I would hazard a guess, you seem like an objectivist, “perich”…or perhaps we should call you…Mr. A.

Also:

“With that put to rest, our only question is: what happened to those students who took “Philosophy of The Matrix” courses? Do they still get to keep their credits, even in light of the shoddiness of the sequels? Do they get their diplomas revoked? Do they have to take a summer class on “Star Trek and Man’s Search for Meaning” to catch up?”

You also seem like a bit of the condescending type (not to mention “condensing” with the utterly boorish reductionism of your criticism).

—

Nick wrote:

“but I saw it as Christian propaganda, if you look at the trilogy as a whole, and as the triumph of Christianity over other, “uncivilized” cultures. Imperialist/Orientalist, something like that.”

Well maybe, but I am just guessing that the one lady-boy, bondage addict Wackowski brother would disagree. Plus you are forgetting your Joseph Campbell archetypes and that BS. It could just as easily be Osiris or any number of sacrificial messiahs of myth. While the Christian allegory fits, I don’t see the film as being at all “pro-christian” in the sense of championing fundamentalist Jesus warriors.

Also the Imperialist/Orientalist dichotomy needs a little bit more textual evidence (or at the least a deeper explanation).

—

Matthew Belinkie wrote:

“My main problem with the second two Matrix movies is: why, oh why, does it never occur to anyone to question how they know they’re really, really out of the Matrix? C’mon people – I can remember at least two Star Trek TNG stories which hinged around people thinking they had left a simulation, but actually just were tricked into thinking they had left the simulation.”

I actually think that is the point of the scene with Neo and the old man looking over the recycling machines. One doesn’t ever leave the “simulation,” the “matrix,” or the “system.” One can leave one “simulation,” but would always be apart of another one.

“So what I thought Revolutions was going to be about is Neo realizing he’s still in The Matrix, and trying to become the first person to get out for REAL. And then at the end, it turns out the real real world is a little less bleak than the pretend real world (there’s still a sky).”

But then what is the real real real world? Smart reading.

—

Two reading recommendations:

http://www.mstrmnd.com/pages/matrix.html

this excellent article (which is annoyingly a flash presentation) does a great job of interpreting Reloaded.

Second,

Read Grant Morrison’s the Invisbles. All the good stuff in the Matrix was knicked (in a perfectly legal and cool way) from it anyway:

Lucifer: “Do you know what Manichean means, Dane?”

Dane: “Sure I do. It’s a bloke from Manchester.”

also, for a similar take on the superior invisible as this article, check this out:

http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=20552