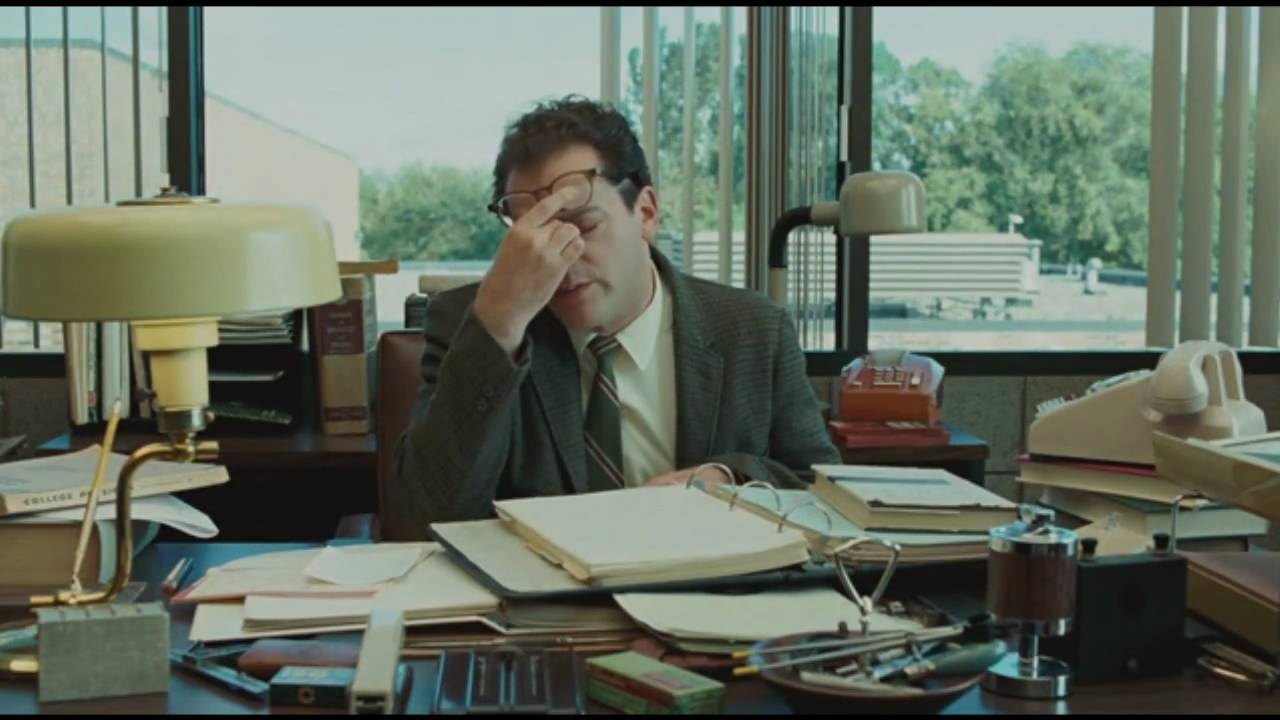

Larry Gopnik: See… if it were defamation there would have to be someone I was defaming him to, or I… all right, I… let’s keep it simple. I could pretend the money never appeared. That’s not defaming anyone.

Clive’s Father: Yes. And a passing grade.

Larry Gopnik: Passing grade.

Clive’s Father: Yes.

Larry Gopnik: Or… you’ll sue me.

Clive’s Father: For taking money.

Larry Gopnik: So he did leave the money.

Clive’s Father: This is defamation!

Larry Gopnik: It doesn’t make sense. Either he left the money or he didn’t.

Clive’s Father: Please. Accept the mystery.– A Serious Man, 2009

WARNING: the ending of most of the movies or TV shows discussed in this article will be spoiled.

Christopher Nolan’s sci-fi action thriller, Inception, ends with Cobb returning home to his children after years of living abroad in criminal exile. Before going to his children, he takes a small top from his pocket and spins it on the kitchen table. This top – his totem – is what signifies to him that he’s in the real world, not a dream of someone else’s creation. If it falls over, as it eventually must under the force of gravity, he’s in the real world. If it doesn’t, he’s in a dream.

Cobb’s children call to him. He runs outside. His children leap into his arms. Back inside …

In 2015, Mad Men, a trailblazer for prestige TV, came to an end after seven seasons. The final season takes place in 1970, capping off the tumultuous Sixties. Every character seems to be left about where we’d expect. Don Draper, the show’s icon, sits on a cliff overlooking the ocean at a sunny Northern California retreat. A guru leads him, and others, in meditation. As he intones the mantra “om,” a smile creeps onto his face.

In John Carpenter’s 1982 remake of sci-fi classic The Thing, an alien capable of duplicating and controlling organic matter infects the researchers at an Antarctic base. One by one, the few surviving humans kill them, destroying the base in the process. After the final climactic explosion, only two humans remain: Macready and Childs. Given the alien’s powers and their time away from each other, neither can be sure the other isn’t an alien. So, as their only shelter burns to the ground around them, they sit. And they wait.

This is a small sampling of ambiguous endings doled out to us in narrative pop culture over the years. Drive, The Wrestler, Lost in Translation, The Color of Money, and even Richard Marx’s 1992 pop ballad “Hazard” all end with a final cathartic piece missing.

Denying catharsis can be a cheap narrative trick if abused. To deny catharsis places one’s work in a postmodern context: denying traditional narratives, emphasizing the ambiguity of life, forcing the audience to look inward with a Brechtian gesture. If your work actually fits into a traditional narrative and you just leave the ending off, it’s more likely to come off as lazy than as meaningful.

But, if ambiguity is occasionally bad, there’s a countervailing tendency that’s universally worse. It’s the drive to squash out ambiguity with one’s own contribution. In the era of universal content and clickbait journalism, you might know it better as the Insane Fan Theory.

No.

The Insane Fan Theory (IFT) is an aggressive reread of a piece of pop culture that exploits some ambiguities to come up with a take that, generously speaking, isn’t present in the original text. Most IFTs completely change the tone of the piece they revisit: from heroic to antiheroic, from comic to tragic, from prosaic to meta.

More to the point, IFTs always function the same way as conspiracy theories do: providing a preponderance of connections but lacking the final motive or warrant that would make them conclusive. They pitch a hypothetical “What if …?” to point your gaze in a particular direction, toss out a bunch of coincidental similarities, then step back like a magician finishing a trick. But there’s no volume of circumstantial evidence, no matter how daunting, that constitutes proof.

Here’s an example: the oddly invulnerable “Ronbledore” theory, positing that in the Harry Potter series, Dumbledore is a time-traveling Ron Weasley. I’ll let you read up on it at The Toast, which sums up the theory with tongue firmly in cheek. Suffice it to say, there’s a load of circumstantial coincidences (a few superficial physical similarities; a lot of deep stretches in throwaway lines) and no real proof.

In [Order of the Phoenix], Draco composes a lovely song – Weasley is Our King. If that isn’t foreshadowing, I don’t know what is. One line in particular is given significance by Draco. He is heard singing it loudly during the game by Harry, and Draco later quotes it in italics – born in a bin. While Draco likes to make fun of Ron’s poverty, the phrase has a double meaning. ‘Bin’ is also a prefix meaning ‘double’ or ‘two’ – think ‘binary’. Was Ron ‘born’ twice? Leading a double life? Is Draco trying to tell us something important?

Where do IFTs come from? Why a sudden surge in popularity? I see two main causes.

First, they originated as a way to show off one’s cleverness and devotion to a pop culture property in online fora. The “Ronbledore” theory came to life on a Harry Potter discussion forum. Many IFTs are born on Reddit or other forums before being aggregated by clickbait blogs. Since social media has democratized our access to platforms, the only ways to stand out as a fan are to be more outrageous, more knowledgable, or both. An IFT lets you demonstrate your encyclopedic knowledge of a text and the outer bounds of your creativity.

In this light, IFTs are distinct from fanfiction or alternate relationship pairings (‘ships’). I’m an outsider to fanfic culture, but I have it on good authority from experts (thank you, Annie K and KFan) that the creators of non-canon pairings generally don’t consider their work to be a Hidden True Reading of the original work. They know that they’re at play in another’s fields.

The Silicon Valley non-canon Jared/Rich pairing (or Jarrich)

Also, I would be remiss if I didn’t call out Overthinking It’s own insane fan theories, including my own unified theory of Schwarzenegger. In my defense, I didn’t mean it. Generally, when I do a deep alternative read on a piece of pop culture, like asking “is Batman a virgin?” I do it not to arrive at a definitive answer but to create a new lens through which to examine questions like “what assumptions of virility do we watch heroic journeys with?” Of course, folks can chime in with their definitive answers anyway, like many of them did in the comments.

Second, we can’t overlook that some pop culture properties have in fact hinged on insane theories – deep readings that were hinted at with “Easter eggs” scattered in the earliest scenes.

The Usual Suspects is probably the ur-property, the ancient pagan ritual from which all hunts for Easter eggs sprang. While there were movies that featured major plot twists before it, The Usual Suspects debuted as the Internet was coming into its own. After The Usual Suspects came Fight Club, The Sixth Sense, and a string of lesser imitators. These films entertained millions. But they also taunted the Internet’s overthinkers: if only you’d paid closer attention to all these clues, you could have seen this coming.

This past season of Game of Thrones confirmed one of the most revered speculations of the last 20 years: the truth behind Jon Snow’s parentage. In a world where something like R+L=J is possible, who’s to say what’s impossible? Why would any literate nerd slack in their diligence for a second?

I want to stress that I’m not judging fan theories as a whole. Overthinking It wouldn’t have much online real estate if we couldn’t traffic in alternate reads of pop culture favorites. The author has been dead for fifty years, and let him stay buried.

I’m objecting to a specific flavor of IFT: those theories that claim to offer a definitive answer to an ambiguous ending.

Let’s use Inception as an example.

In the quest to find a definitive answer on whether or not Cobb is dreaming at the end of Inception, some cineastes have come up with remarkably complex theories. Here’s some person on Reddit:

Once a dreamer becomes aware that they are dreaming (becomes lucid), they gain the ability to manipulate their reality within reason. This is why the team was able to summon guns out of nowhere and how Eames is able to project himself as different people.

Cobb’s reality check is to assume that he is in fact dreaming and attempt to bend reality. In this case, he focuses on making the top keep spinning. If it topples despite his focus, then it must be reality; but if he is able to keep it spinning indefinitely, it must be a dream. Notice how intently he stares at the top whenever he spins it.

This theory lends special credence to the end of the film. Cobb spins the top and walks away. The top is wobbling, obviously preparing to fall over, but this doesn’t prove anything since without Cobb willing it to behave strangely this will prove nothing. However, notice that Cobb isn’t watching anymore. He doesn’t care if the top spins or falls because this reality is where he wants to be, dream or not.

I understand the desire to find a definitive answer to an ambiguous ending. And I don’t want to prize authorial intent too highly. But, to the extent that we can determine intent, we have to consider it. And the author’s intent with an ambiguous ending is clear: ambiguity.

If Christopher Nolan wanted us to see the top fall over, he would’ve filmed it falling over. It’s not as if he ran out of film. If he wanted to show the top spinning forever, that’s trickier to depict, but we can imagine feasible ways. Instead, he showed neither.

What does that mean? It means that we can’t know one way or the other. It means that we can’t tell the difference between a sufficiently vivid dream and reality. It means we can willingly abandon the tool that distinguishes between reality and dream if we find the promise of the dream compelling.

And, of course, Nolan himself has reasserted that ambiguity—explicitly, and needlessly I contend—in a 2015 commencement address at Princeton:

Nolan added: “The way the end of that film worked, Cobb, he was off with his kids, he was in his own subjective reality.

“He didn’t really care anymore, and that makes a statement: perhaps, all levels of reality are valid. The camera moves over the spinning top just before it appears to be wobbling, it was cut to black.”

The director accepted that audiences weren’t quite satisfied with such vagueness: “I skip out of the back of the theatre before people catch me, and there’s a very, very strong reaction from the audience: usually a bit of a groan.”

Let’s take a less metaphysical example: the finale of Mad Men. Many people interpreted the overlay of the Coke commercial over Don Draper’s meditative gaze as evidence that Don Draper returned to New York and pitched the Coke ad. It made a certain sense. Coca Cola was a big client for McCann Erickson, the carrot held out by Jim Hobart in S7E11 “Time and Life” to keep them from fighting the merger. And Don’s greatest gift has always been his ability to pathologize the zeitgeist as a commercial product.

But the Coke ad, unlike many of Mad Men‘s most famous pitches, is an actual historical artifact. It was made by a real person: Bill Backer, creative director at McCann Erickson. Mad Men was certainly willing to rewrite the historical record before—Jaguar never signed with SCD&P—but that’s quite an edit.

Also, the finale didn’t shy away from showing definitive endings where it wanted to be definitive. Joan has started a new ad agency. Pete and Trudie are back together as Pete starts his career with Learjet. Peggy and Stan appear to be giving it a go as a couple. There’s no ambiguity there. When Weiner wants to be definitive, he can be.

So the beatific smile that Don wears in that final shot may be just that: a moment of peace. We don’t know where he’s going to go from here, or if he’ll ever leave. We don’t have to know. He’s come nearer to terms with who he is as a person.

I could go on. We don’t know whether Childs or MacReady is an alien at the end of The Thing because Carpenter wants us to remain unsettled and paranoid. We don’t know how the final pool match in The Color of Money between Eddie Felson and Vincent Lauria turns out because the winner isn’t the important thing. What matters is that Eddie is back in the game at all.

And yes, again, the author is dead; we can read the work with any lens we like. But I think we lose something as critics, as an informed audience, if we try and read something that’s clearly not there. We can credit Nolan, Weiner, Carpenter, and Scorsese with enough skill to make a definitive ending if they want to. That they left it mysterious means they want us to accept the mystery, to meditate, however briefly, on the ambiguity.

I think this sort of Insane Fan Theory bothers me more than most for existential reasons. There’s a real value in embracing the journey over the destination, contemplation over possession, expression over mastery. Sometimes you need to just let a powerful moment wash over you without struggling to define it. If that sounds like hippie nonsense, then live a few more years and get back to me.

But the next time you find yourself chafing at an ambiguous ending, take a deep breath and look back a minute or two. Maybe the director stopped the film there because the thing they wanted you to pay attention to already transpired. Maybe there’s a subtler point being made.

In the final scene of the Coen Brothers’ 2009 comedy A Serious Man, Larry Gopnik grapples with a student’s failing grade, a grade he’s been bribed to change, and has been threatened with a defamation lawsuit if he doesn’t. Finally, he changes the grade to a C-minus. Just then, he receives a telephone call: his doctor asking to speak to him about some X-ray results. Meanwhile, his son Danny stares over the horizon with the rest of his classmates as an ominous black tornado advances on the school.

The temptation is to view this as punishment for Larry’s dishonesty. But Larry’s been punished continually since the start of the film: his brother’s condition deteriorating, his wife leaving him, getting kicked out of his home, his tenure position up in the air, and so on. If the tornado is punishment for Larry’s dishonesty, why is it being visited on Danny? If the bad X-ray results are, then what were all the other misfortunes a punishment for?

No strangers to ambiguous endings, the Coen Brothers arranged these events to befall Larry to challenge our notion of narrative causality. They end where they do to force us to meditate upon the ambiguity. Why should any other director who wants us to focus on the journey, and not the destination, do otherwise?

Then the LORD answered Job out of the whirlwind, and said,

Who is this that darkeneth counsel by words without knowledge?

Gird up now thy loins like a man; for I will demand of thee, and answer thou me.

Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? declare, if thou hast understanding.

– Job 38:1-7

I don’t think it’s possible to have this conversation without at least mentioning The Sopranos. While most of these films and TV shows end on an ambiguous note, they do end on a completed one. The Sopranos ends mid-note (“Don’t stop-“), leaving us no other option but to speculate what happens next. Did Tony die? Did he live on to finish his onion rings? Was this all just a clever ploy to get the audience to share in a collective panic attack like our protagonist? All we’re left to meditate on is a lingering nothingness and then credits. Where do we go from there? Anyway, great post!

So an article about overthinking stuff on a website called overthinking.com. Bored at work or irony?

^ To the person above who also seems to go by Greg: What are you getting at? Should this site about overthinking pop culture not be about overthinking pop culture? Enthrall us all with your wisdom…

“Let’s take a less metaphysical example: the finale of Mad Men.”

How’s this for a metaphysical IFT? Don doesn’t go back to NY, nor does he stay in the commune; at the exact moment he gets the idea for the Coca-Cola ad, he hears a bell and he attains a kind of commercial nirvana/enlightenment and he leaves the material world to become the True Spirit of Advertising. This explains why there’s no more Don, yet the ad exists as created by the real-life ad man.