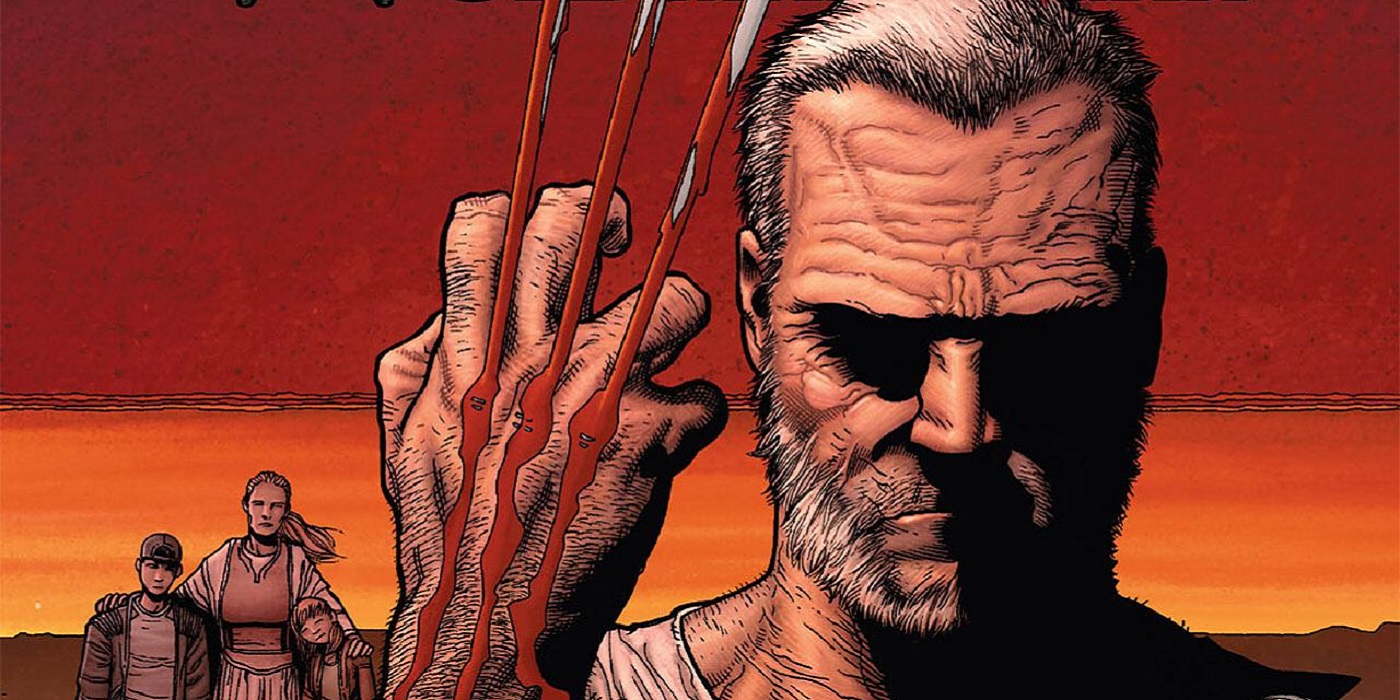

Logan – the tenth movie in the X-Men franchise of films – takes its characters and storylines from a number of different sources in the original comics.

The clearest influence comes from Old Man Logan – in an alternate future where supervillains control all of America, a retired Logan is hired by Hawkeye to drive from California to what used to be Washington, D.C to deliver a mysterious package. In the movie, that “package” is incarnated as a young girl named Laura, eventually revealed to be Logan’s daughter (conceived in-vitro by a genetics company that had acquired DNA from various mutants) who requires transport to “Eden,” a location in North Dakota from which she can escape north to Canada, where apparently mutants are a protected class.

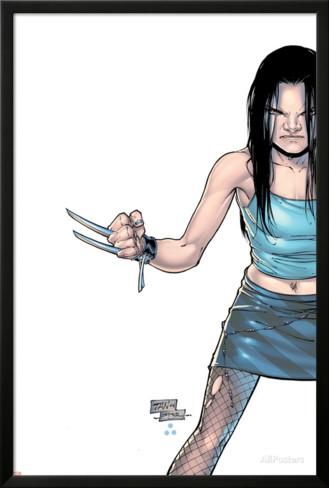

The character of Laura, in the comics, is more commonly known as X-23, a mostly-clone of Wolverine made from samples of his DNA (sequences containing the Y-chromosome were damaged, so the geneticist replaces it with a duplicated X-chromosome instead, yielding a female genetic twin rather than a proper close per se). While in the comics, X-23 is rapidly aged up into adolescence, characteristics like her being largely mute and her self-harming tendencies are key to her depiction in Logan.

The idea that no new mutants have been born in twenty-five years, though – making Laura and her friends, artificially created as they may be, vitally important to Xavier and Logan – comes from the X-Men storyline “Generation Hope.” In the comics, millions of mutants across the world lost their powers on “M-Day,” when Scarlet Witch suffers a nervous breakdown and declared “no more mutants,” leaving the mutant population somewhere under 200. Sometime later, a young girl was detected who was believed to be the first mutant born since the Decimation event – a girl named, appropriately enough, Hope.

So in the movie, the reason for the mutant extinction has changed (spoiler warning: genetically modified corn), and the identity of the new mutant who must be protected has changed, but the essence of the story is the same: drive across America, protect this little girl at all costs, because she is the last hope for the mutant species.

Except that in Logan, unlike in the comics that inspired it, that hope is very much in vain.

Both the tone and the overarching themes are relentlessly dark, certainly darker than any other superhero movie (with the possible exception of Watchmen, which arguably may not count). Logan does manage to deliver Laura and her friends to safety, and kill all the bad guys, but the film’s final message is one of utter hopelessness: mutants have no future in America. The age of heroes is over.

Throughout the film, Logan positions itself as presenting a critique of the mythologies that human civilization has used to guide us. It does this in three ways: classical mythology is represented in the movie’s structure, and modern mythology is symbolized diegetically by the Western movie and by the semi-metafictional presence of X-Men comics within the storyworld of the film.

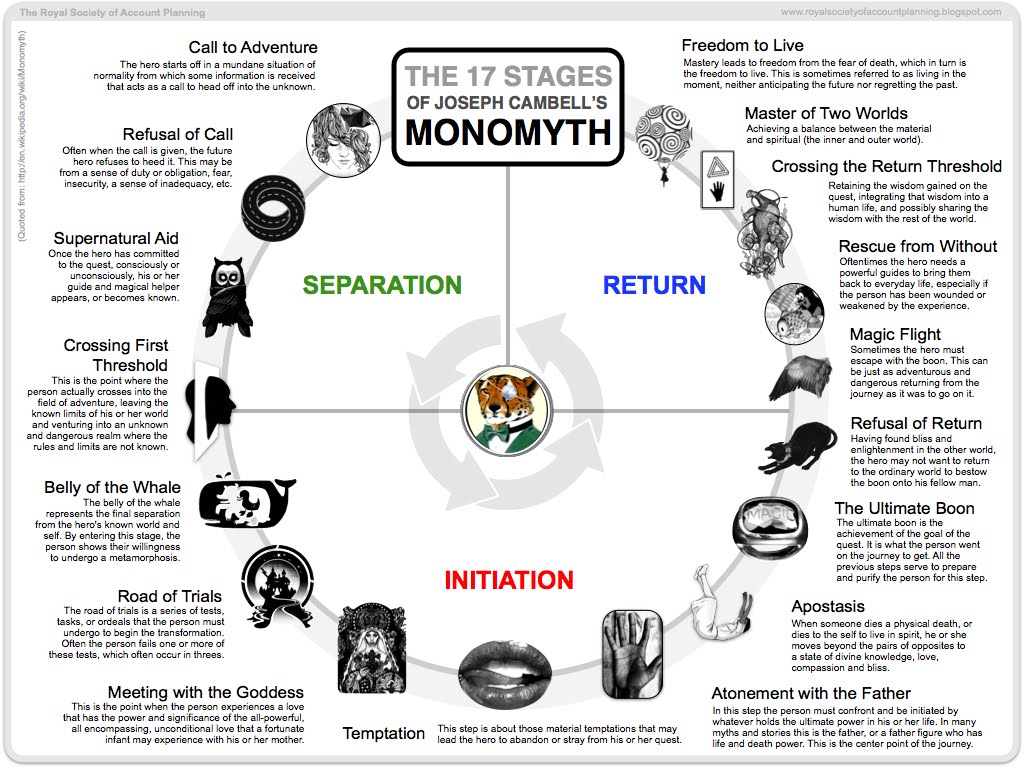

Logan’s plot adheres very closely to the structure of the Hero’s Journey as most famously theorized by mythologist Joseph Campbell, and variously adapted by others over the years. In one sense this is just good screenwriting – the Hero’s Journey, or monomyth, is considered to be the prototype of storyness in the human mind, and a writer who wants his or her story to resonate in this particular way can use it as a conscious plotting mechanism for the reason that part of what we mean when we identify something as a story is that it mirrors this specific pattern of events to some greater or lesser degree.

In one way this is just standard screenwriting advice, but on a deeper level it’s a comment on the role and meaning of the concept of the traditional hero in a world (portrayed in Logan as postapocalyptic – at least for mutants) that has run out of patience for the whole concept of heroes. A hero is special precisely in that he or she is set apart and in opposition to the “ordinary world.” The hero’s journey is one of leaving the ordinary world, descending into a special, highly symbolic world, and then returning with transcendent knowledge or artifacts that are then synthesized into the fabric of the ordinary world, rescuing or at least improving it.

In Campbell’s monomyth – synthesized from analyses of mythology from Greece to Arabia to Japan – the hero usually has some kind of miraculous birth or special lineage; this is certainly true of mutants in the Marvel Universe, whose whole deal is that they are born with a certain gene activated in them that regular humans haven’t got, which manifests around adolescence as an extraordinary power or uncanny ability.

Logan experiences a Call to Adventure (being asked to help Laura escape to Eden) and refuses it hard before reluctantly accepting Crossing the First Threshold (actually the Mexico-U.S. border) into the Belly of the Whale (America) and experiences a Road of Trials (the actual road that leads from the Mexican border to the Canadian one). His “Meeting With the Goddess/Woman as Temptress” stage is represented by the family dinner with Munsen family that creates a temporary, false sense of home, which is immediately followed with his “Atonement with the Father,” i.e. the death of Professor Xavier at the hands of X-24 (Logan’s clone, or “brother/shadow” in Campbellian/Jungian terminology, whom ultimately Logan kills using the “talisman” – the adamantium bullet he had planned to use to kill himself; and in a way he does just that, which is Logan’s interpretation of Wolverine’s “killing” his superhero persona after being responsible for the death of the X-Men in Old Man Logan, something that, in the movie, was actually carried out by Professor Xavier instead).

Another oblique structural reference to classical mythology is in Logan’s synthesis of the “box” from Old Man Logan with Hope from Generation Hope into Laura/X-23. A box of hope, of course, immediately puts us in mind of the story of Pandora from Greek mythology. Pandora was the first woman created by the gods, who opens a mystical box which releases all sorts of horrors into the world – by the time she gets it closed again, the only thing left inside is hope. Transigen, through their genetic and military experimentation, has filled America with destruction for the mutant race; Laura, then, the last remnant of Transigen’s work, must be protected at all costs, as she represents the only example of hope available for the existence of mutants in the world.

While I was watching the movie, I thought that it had some third act problems – a pretty common symptom in Hollywood – but thinking about it later I realized that Logan was actually messing with the order and orientation of the last few stages of Campbell’s monomyth structure in order to deliberately subvert them. Logan never crosses the return threshold, never becomes master of two worlds, and his “freedom to live” is enacted in a bitterly ironic way: he dies saving Laura, and while he has long since lost any fear of death (rather his only fears are for the suffering and death of others) the freedom he really gains consists in his acceptance of the irreversible extinction of the mutant species.

Before comics were ever referred to as American mythology, this was the role of the Western film. Logan contains a scene where the characters watch the classic Western Shane. Historically it’s situated between the kinds of films that unreflexively lionized the conquest of the American West and either ignored or actually supported the destruction of the native population, who were portrayed as bloodthirsty savages (such as 1939’s Stagecoach), and later films (so-called “Revisionist” Westerns such as those directed by Clint Eastwood in the 1960s and 70s) that complicate and interrogate the role of European colonialism and the dehumanization of Native Americans in earlier films and actual history).

Shane is about the end of an era, is essentially meant to be a eulogy for the cowboy-type that symbolized America in the early-mid Twentieth Century. The kind of hero that Shane was – the gunfighter delivering frontier justice in regions where the legitimate law had yet to penetrate – no longer had any role in the world, and had to be replaced. The scene from Shane that Xavier and Laura watch is later quoted verbatim by Laura as Logan’s eulogy, driving home the film’s message that all of our historical mythologies have failed us, and a new kind of hero will need to arise.

Logan himself was born in the mid-1800s, and the comics’ and films’ depiction of his origins are heavily influenced by Westerns; that was the context in which the character grew up and lived much of his early life, for instance participating in the Yukon gold rush at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th Centuries. In this sense, Wolverine represents the transition between the Western hero and superhero as mythological figure.

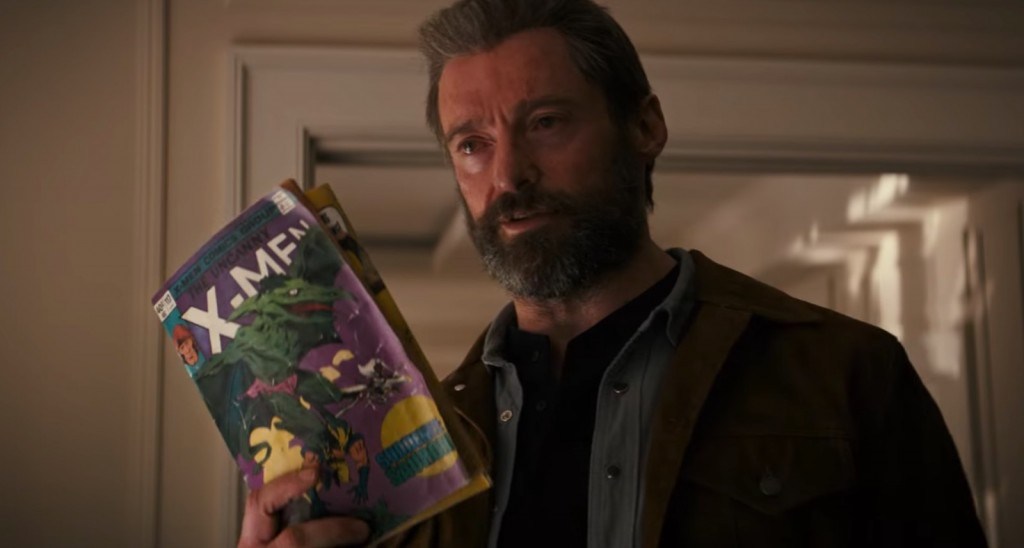

Thus, the third and final evocation of mythology is in the repeated appearance of X-Men comics within the movie itself. We’re shown that someone has been publishing comics based loosely on the real-life adventures of the X-Men. According to Logan, only about a quarter of it really happened, and what did happen didn’t happen like that. This leads Logan to doubt even the existence of Eden, dismissing it as wishful thinking from a desperate reader. The existence of comics featuring “real life” superheroes is straight out of the Marvel comics, where official, semi-official, and unofficial publications depicting the heroics of the Fantastic Four, Avengers, X-Men, and others are occasionally referenced.

Why are these comics brought into the film only for Logan to dismiss them? In part they serve as a convenient means for Laura’s surrogate mother to learn about Eden (which does in fact exist, raising the question of who the writers of these comics are and where they’re getting their information), but they’re also symbolically important as another reference to mythology. Superhero comics have often been called “modern mythology” or “American mythology,” as they are where we in the contemporary world get most of our ideas about heroism. It’s not hard to see how superhero comics have inherited the role that mythology played in earlier civilizations, particularly with comics frequent adaptation of mythological figures like Thor, Hercules, and so on.

The three generations of mutants who are the focus of the story in Logan are linked directly to the sorts of superheroes depicted in comics over the decades. Professor Xavier is the “Golden/Siver Age” hero, idealistic but humanized. Logan is the “Bronze/Modern Age” anti-hero, cynical but resolute.

Not coincidentally, both of these heroes of the past are dead before the end of the movie. Only Laura and her friends remain, and it’s yet to be seen what kind of heroes they will be – if they choose to identify as heroes at all. Because whoever you want to identify with the Forces of Evil in this movie, they’ve either already won or are very close to winning, and hope can no longer consist in (personal, political, or revolutionary) resistance to those forces but rather must manifest as a kind of righteous resignation.

Mutant heroes – people born with powers that make them special and different from ordinary humans – first appeared in Marvel comics in the 1960s, and were at the height of their ubiquity in the zeitgeist in the mid-80s through the late-90s. Since then, they’ve been eclipsed by superheroes who acquired their powers through accidents or their own hard work, such as the Avengers. In the comics and now in the cinematic universe too, the mutant species has been driven to near-extinction more than once (with Grant Morrison’s unforgivable, J.J. Abrams-like destruction of the mutant homeland Genosha in the 2001 storyline “E is for Extinction,” the Decimation by Scarlet Witch in 2005, and in current continuity the discovery that Terrigen Mist – the substance that causes superpowers to emerge in certain people, known as Inhumans, whose ancestors’ genes were tampered with by alien races known as the Celestials and, later, the Kree – a cloud of which is now circling Earth in the Marvel Universe, is fatally toxic to mutants. Most of the mutants who haven’t died from contact with Terrigen have been relocated – perhaps permanently – to Limbo. Now, this could all be attributed to Marvel deliberately trying to tank the X-Men franchise and force the film rights to revert to them from 20th Century Fox, the studio that currently holds them. But it also could be that the metaphor of mutants has ceased to resonate in contemporary society, and we need something different from our superheroes than we did fifty or even twenty years ago. The whole tenor of the conversation about identity has changed dramatically since mutants were the dominant metaphor operating in superhero comics, and this shift is part of what’s being expounded upon by director James Mangold in Logan.

In Generation Hope, Hope herself expresses opposition to Charles Xavier’s whole philosophy; she believes that the idea of having a school “For Gifted Youngsters” only perpetuates the divisive ideology that both Xavier and Magneto have been trying, in their different ways, to uproot (Xavier through peaceful dialogue and education; Magneto variously through mutant separatism or supremacy). This could be a means of giving voice to a criticism of contemporary identity politics or intersectionality that a younger generation may perceive as doing more harm than good, no matter how righteous the intention. Laura in Logan doesn’t echo Hope’s sentiment – but then, of course, there hasn’t been any School for Gifted Youngsters for a long time, and for all we know there may be no more than a handful of mutants in the whole world.

Logan saves Laura, but there’s nothing to be done about the world at large. There’s a deliberate attempt here to parallel the intentional decimation of mutants in Logan with the genocide of Native Americans by European colonists, which is demonstrated through the quotes from Shane and the cowboy garb that the three mutants acquire in Oklahoma City. The extent to which mutant culture exists in Logan’s future America is, at best, a pale shadow of its former self, just hanging on at the absolute periphery of society.

Logan leaves the future of heroism a little bit open – just the tiniest crack – but there is a pervading sense of doom that seeps into you when watching it. Its message is extremely pessimistic. But with its quotations and subversions of prior and, in its view, obsolete visions of heroism and the heroic, the movie’s thesis statement is quite clear: what may have worked in the past is not going to work in the future. So we’d better come up with something new. Or else.

The other thing to consider is that mutants were clearly a metaphor for anyone ‘born different’ and hence disenfranchised simply for existing – Jews, women, African Americans, etc. Perhaps Xavier’s dream of peaceful co-existence is the dream that has been lost – The death of Xavier and Logan can be seen as a triumph of racist, sexist America. Hmm… this seems to remind me of something

Thanks for the interesting article,

bt

Thanks Richard Rosenbaum!

I was disturbed by Logan because of its hopelessness.

I read your article as a hopeful take on hopelessness. That is great. You seemed to say that we are not entirely into a hopeless state yet, so we can still change and correct if we learn the right lessons from “Logan.” Thanks a bunch!

I am personally opposed to the victim-centered culture and shaming tactics of modern political correctness. I read your interpretation of “Logan” as a critique of that same movement, so I see a lot of hope in that interpretation. If we can see that what we are doing is not working, and will only lead to decimation and despair, we can change. We can learn. We can grow. We can be different.

Great article. You touched on something very particular about Logan that it is the absolute end of the franchise (unless they finagle another Days of Future Past retcon somehow) and that for all we know all the X-Men we like are all dead. The radio denotes about 7 deaths when the school is destroyed, easily taking Jean, Cyclops, Storm, Beast and perhaps Iceman, Kitty and Rogue and possibly Quicksilver or Colossus; depending on how far the continuity extends and whatever kind of changes ensue after Apocalypse but also after DOFP (Goddamn time travel is confusing.) There is no mention of what happened to Magneto but maybe it doesn’t matter right now. It takes a certain amount of narrative courage to say, at least for the moment “All those nice people we made all those movies with? Frickin’ DEAD. No more adventures, no more antics, no more saving a world that fears us” and while I found this very disheartening at first, the more I think of it it’s kind of brilliant.

I’m tempted to say it’s meta-references (the comic books) were an almost Brechtian attempt to undo the very myths the films create. Much like Unforgiven, it attempts to dispel with the niceties of it’s heroics and say “no, this dream, this narrative we tried to create really didn’t work and a LOT of people died really badly because of it.”

It’s very odd then that in a way the film is the exact opposite of Days of Future Past where everything is fixed leading a ludicrously, almost hilariously utopian vision of the school with action and time travel shenanigans (and also because Charles convinces Mystique NOT to shoot someone but moving on.) So in a way the film rejects a notion of it’s own franchise in an interesting kind of thesis/counter-thesis.

However the film’s understanding of GMO’s is a bit wonky. I mean even the most basic fruits and vegetables we eat in America have been genetically modified through specific strain cultivation for centuries, and generally genetically modified plants and vegetables don’t have any side effects in eating them (at least I don’t think so, I’m not a botanist so feel free to toss examples) there is some arguments made for other kinds of human malfeasance on the environment; pesticides that kill bees and bats, over farming, destroying habitats for sake of grazing land etc. I do think the idea of high fructose corn syrup being used to weed out mutant populations is interesting.