AMC’s Better Call Saul ended its second season a few weeks ago, which has given us plenty of time to discuss and debate every angle of this excellent season of television. Real-life lawyer Rachel D. kicks things off by providing some insight about how the legal profession is depicted in the show.

Spoiler Alert for Seasons 1 and 2 of Better Call Saul. If you haven’t watched the show yet, go binge watch it, and meet us back here when you’re done.

Ryan Sheely: Something that has struck Rachel about Better Call Saul is the way that the practice of law is depicted relative to other legal shows. Rachel, want to elaborate?

Rachel D.: I really like how the profession is not depicted as being glamorous or fun. It is really rare to see lawyers depicted as stressed out and depressed people. On most legal TV shows, everyone is impeccably dressed and talking at a Sorkin-esque.

Richard Rosenbaum: And most of the job is paperwork, phone calls, etc.

Rachel: Even on a show like Crazy Ex Girlfriend, the protagonist is always super competent. It’s as if the job were so easy that she can completely focus on her personal life stress.

In contrast, on Better Call Saul, the routine drudgery of law practice is portrayed vividly. A good example is the document review room where Kim is sent to work in Season 2. This is where a lot of the legal research for litigation cases actually happens, and I can’t think of another legal show where that is presented. The feel of this space is incredibly accurate, down to the rap music they are playing on shitty speakers.

In contrast, on Better Call Saul, the routine drudgery of law practice is portrayed vividly. A good example is the document review room where Kim is sent to work in Season 2. This is where a lot of the legal research for litigation cases actually happens, and I can’t think of another legal show where that is presented. The feel of this space is incredibly accurate, down to the rap music they are playing on shitty speakers.

I also think law firm hierarchy is depicted well. On other shows, you would think law firms are totally flat structures and associates “talk back” to bosses so much more than they ever would.

I love how the relationships between Kim and the partners are depicted-tense, awkward, deferential. So yes-I like the show’s depiction of the profession because while I can’t say everything that happens is totally accurate or plausible, it gets at some of the emotional truth of practicing law.

I love how the relationships between Kim and the partners are depicted-tense, awkward, deferential. So yes-I like the show’s depiction of the profession because while I can’t say everything that happens is totally accurate or plausible, it gets at some of the emotional truth of practicing law.

Sheely: I think the status differences are illustrated really well. The partners all get to tell these long, circuitous stories and Kim just has to take it. At Davis and Main, the partner gets to play his acoustic guitar to blow off some steam.

I mean that is a huge part of the Jimmy character and why he struggles in the profession- he doesn’t intrinsically respect the authority embedded in the status hierarchy. This is summed up in the last scene of S2E1, where he deliberately disobeys the sign in his fancy new law firm office that says that the light switch must never be turned off. Once is told that something must “always”be done, he is compelled to break that rule.

Peter Fenzel: Breaking Bad was also invested in this idea of exploding and reconfiguring the signifiers embedded in our hierarchies, language and iconography around various types of economic activity, and it’s cool to see Better Call Saul do it as well.

There’s all this stuff in so many TV shows about certain sorts of high status, rich, powerful professions, but rich and powerful in a specific context, and all sorts of little things about them that are code and layered on, like great teeth and hair, or specific sorts of sexual appetite, and one thing they do is separate one kind of economic activity (on the micro scale) from another, which is what we do in real life as well.

There are a bunch of “wow isn’t this weird and fun” iconic moments I can think of that play with this, but the Vince Gilligan shows are doing something more. It makes me think of Boiler Room and the adoption of rap music by “bro finance” (as distinct from yuppie finance, sports car finance, or county club finance; there are a lot of varieties) or particularly the Prius that shows up in Weeds driven by a drug dealer because it is good for drive-bys.

But those to me embrace the cleavages here as salient; they reflect a difference and reinforce the difference while confounding it by showing how funny something is out of context.

So doctors look a certain way on TV, and drug dealers, good or bad, look a different way. A big part of it is racial, but it’s also in a lot of details in clothes, behavior, etc. And the way they look is more calcified in their social status than the money they make is. We get closer to something like what Better Call Saul and Breaking Bad do when Stringer Bell goes to community college in The Wire, but not from a lot of the other characters in The Wire, who, for their merits, do tend to stick petty close to their socioeconomic signifiers within racial capitalism.

But Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul go past that, like how in the former Saul (Jimmy) discusses the difference between a criminal lawyer and a “criminal” lawyer. You have lawyers and teachers and you have drug dealers and assassins, and people do throw out their signifiers, but they are confounded by the story constantly and are mutable and change.

A huge one in Breaking Bad was Walt’s shaved head, which in the context of a white teacher means either nerdy baldness or cancer, but in the context of Chicanos is much more common to just have in different social stations. So you have these bald heads on white men who are crossing over into Hispanic cultures where their bald heads shift in what they mean. And things like the Pontiac Aztek that mean something very specific about a specific sort of racial capitalist idea of family, become absurd and complex at once when Walt becomes involved.

Gus Fring goes the other way – in white dominated fast food culture, his reservedness and quiet instantly mean something else than in the Hispanic dominated cartel culture.

Better Call Saul seems less specifically invested in the dichotomies here of “law abiding or high class white people” and “criminal or low class people of color” and the twisted exoticism that festers around it in the heart of our culture, but it’s still around.

Instead it applies the same idea to a more subtle set of inauthentic signifiers, like the hyperreality mapped on to TV law firms. Not to spoil anything, but in season 2 it does some awesome stuff with hospitals, and how completely terrifying they can be, but generally aren’t outside the context of zombie or horror movies.

To take it to a simpler, specific place, I love how hard the show wants you to think Howard is this villain, because he has every characteristic of a villainous TV lawyer. But then he’s actually something quite different and more complex, and it’s not just confounding for the sake of confounding.

To take it to a simpler, specific place, I love how hard the show wants you to think Howard is this villain, because he has every characteristic of a villainous TV lawyer. But then he’s actually something quite different and more complex, and it’s not just confounding for the sake of confounding.

Kim Wexler is a triumph in this regard in so many ways, among other things, she’s an unbelievable take-down of Ally McBeal. Just eviscerating.

Rosenbaum: I absolutely agree about Kim. This is why she is so convincing and compelling: she is clearly very, very good at her job, and yet we are shown not only that she puts in an extraordinary amount of effort to be that good, but also that she has a very high (and highly realistic) degree of status anxiety related to it. She has a strong need for independence but it’s nuanced – she doesn’t reject help out of hand, but she always takes care to ensure that she will be rewarded only for what she herself has worked for. That’s why seeing her be happy is so gratifying for the audience: she sets high standards for herself, but not unrealistic ones, and she is capable of recognizing and celebrating her victories in ways that other TV “professionals” often aren’t (let’s say the brilliant but generally anhedonic House, for instance).

Along these lines, is Chuck McGill the worst, or what?

Sheely: Yeah, he really is. I mean let’s start from the two scenes that bookend the season finale. The first scene is a flashback to when Jimmy and Chuck’s mom is dying and the last scene is Chuck manipulating Jimmy into confessing to document forgery while a hidden tape recorder takes it all down. Both of these scenes show that Chuck is just as manipulative and ethically creative as Jimmy. In the case of their mother dying, Jimmy misses her calling out for him with her dying breath, and Chuck deliberately withholds this from him when Jimmy gets back. In the last scene, Chuck plays on Jimmy’s sympathy by feigning that he has been pushed to a breakdown and threatening to retire from the law, getting Jimmy to confess.

Sheely: Yeah, he really is. I mean let’s start from the two scenes that bookend the season finale. The first scene is a flashback to when Jimmy and Chuck’s mom is dying and the last scene is Chuck manipulating Jimmy into confessing to document forgery while a hidden tape recorder takes it all down. Both of these scenes show that Chuck is just as manipulative and ethically creative as Jimmy. In the case of their mother dying, Jimmy misses her calling out for him with her dying breath, and Chuck deliberately withholds this from him when Jimmy gets back. In the last scene, Chuck plays on Jimmy’s sympathy by feigning that he has been pushed to a breakdown and threatening to retire from the law, getting Jimmy to confess.

Both of these are cons that are right in line with the kinds of thing that Jimmy routinely does, both in his career as an ethically flexible lawyer, and in his prior career as a small-time grifter.

But definitely fly in the face of how Chuck (well, and really everyone) sees both of them. Honest, lawyerly Chuck, and dishonest “Slippin’ Jimmy”

What do you guys make of this, based on what we were discussing about the legal profession?

Rachel: Like you were saying earlier, for Jimmy, I think there is a sense of the legal ethics rules being arbitrary. As a result, he is willing to ignore rules if he thinks it is in service of something better.

Sheely: Do you think this is what Chuck also exhibited in the two vignettes in this episode? Or is his behavior something different?

Fenzel: I think for Chuck rules are a continence. They exist in opposition to inherent qualities of human nature, constraining it. Chuck lets on that he loves rules because he sees the world and the self as naturally ordered, but really he loves rules because he sees the world and the self as naturally chaotic. The cognitive dissonance there is what produces his medical condition. This is why he can’t tolerate the existence of Jimmy, a man okay with or who even promotes disorder and is not punished for it.

One theme that runs through the show is “How does what other people do to me affect what I do to myself?” And Chuck is the worst, because in response to what Jimmy does to him, which is mostly small, inadvertent humiliations or inconvenience, or merely existing, Chuck incapacitates himself and relies on the charity and compassion of others, but when others threaten his worldview, he suspends his incapacitation at will to strike at them with deep cruelty.

Or maybe it’s not that, but “How does watching people do things to other people affect what I do to myself?”

There are a lot of characters imitating or reacting to events or characters as a third party. It’s a whole show of third parties.

Which fits in a cool way with an idea of what attorneys are and what they do.

Rachel: I think one scene which really encapsulates what Pete is describing is the flashback scene to Jimmy in the corner store spotting the con man. Here he is conflicted and yet he decides to not let his father benefit from the sale of the carton of cigarettes. He instead imposes his little tax and keeps the money.

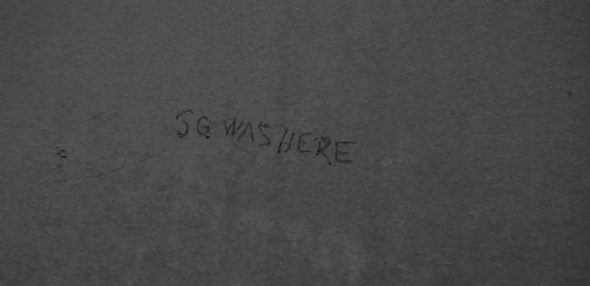

Fenzel: The flash-backs and flash-forwards are full of rich character moments like this. One of my favorites is by the Cinnabon mall dumpster, where he accidentally locks himself out of the mall and would have to set off the fire alarm to leave. None of the intent of this system has anything to do with him; it’s between the Nebraska mall and the thieves it’s trying to deter and the police. But Jimmy ends up in the middle of it, and he has to make a decision about what to do, yes, because of the threat of talking to the police, but also he has to have a disposition about it in what he does to himself. And he punishes himself, just sits down to wait it out, perhaps for hours. He is in a place where he chooses to deepen his suffering.

And he has his tiny act of rebellion, scrawling on the wall. “SG was here” can be seen as another “little tax.”

What do these “little taxes” have to say about the big themes of Better Call Saul? How do the emerging themes of this show contrast with Breaking Bad? Come back next week for the conclusion of our discussion of Better Call Saul.

Add a Comment