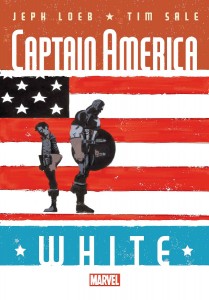

For Week 20 of our Reading List series, we examine just one recent comic, the finale of Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale’s Captain America: White.

Captain America: White #5

Marvel Comics

This final issue of Captain America: White is about compromise – and hypocrisy. In December, 1941, Captain America, Bucky Barnes, and Nick Fury and his Howling Commandos are behind enemy lines, in Nazi-occupied Paris, where the Red Skull is planning to destroy the city – “As Paris falls,” he says, “so falls the world.” By destroying the cultural centre of Europe, he intends to wipe out the culture itself and break the hearts and spirits of those who hold it dear. “A world ruled by Germany,” he claims, “is the future.”

Atop the Eiffel Tower he holds both a tied-up Bucky and a bomb. He insists that Captain America can save only either Bucky or the city, but not both. Of course we know that the whole thing about superheroes is that they’re not subject to the same kinds of logical limitations as we mere mortals. We know that Cap will save everyone. What’s interesting here is the philosophical implications of the way that he does it.

Red Skull presents Captain America with a false dilemma: “You can save Paris – or your partner.” It’s the kind of choice that you present to a child when you want them to do something, framing the options in such a way that they feel like they’re making a decision when in fact you’re making the decision for them. Here the Skull is doing the opposite, creating a no-win situation for Cap in order to put him into a cognitive box wherein he can be controlled.

Cap, of course, is too smart for that to work, but how often do we fall for that very fallacy? “Why should we invest in space exploration when there are still so many problems here on Earth?” or “How can you believe in God and evolution at the same time?” or what have you. What it boils down to in the political subcontext of Captain America here is: if we can’t do everything, why do anything? This is illustrated by Red Skull presenting Captain America with his false dillema in one breath and in the next telling Bucky, “You Americans think you can come into any country in the world as if it were your own.” Bucky helpfully points out the Skull’s hypocrisy: “Last time I checked,” he says, “you krauts don’t belong in France. Or Poland. Or Austria. Hungary. Czech – ”

To which the Skull replies, “SILENCE.”

Great argument there, Johann.

Captain America does both things at once – saving Bucky and Paris – by doing just one thing: kicking the living crap out of the Red Skull. And while he does so, the captions read: “I got into this war – this uniform – to stop men like The Red Skull. Was I naïve to think that one man – particularly if it were me – could make a difference? Or is that why I wear the flag of the greatest country that ever was? Because no matter the odds, if we don’t fight for those who can’t – who will?”

Again, those aren’t mutually exclusive, are they? We’re presented with all these seemingly conflicting options and in order to stay logically consistent we seem to be forced to choose between them. And yet we’re not. Captain America knows that he is Captain America, but he also remembers what it’s like to be a helpless kid. He can break through Red Skull’s (and, for that matter, the French Resistance fighter, Marilyne’s) accusation that Americans act as if they own the world and invade France without falling into a quagmire of moral equivalency with the Nazis. Once Cap saves the day, Marilyne even admits as much: “I have learned too that you Americans are not all bluster and noise. But we French will deal with the Nazis.” Remember that the French Resistance, heroic as they were, were dwarfed in numbers by collaborators and collaborationists, not to mention the Vichy government, which enthusiastically executed Germany’s wishes. The French were not uncomplicatedly good guys, just as (Captain) America’s actions cannot ever be purely pragmatic, purely ideological, or perfectly morally unambiguous. The easy part about fighting the Nazis, as Steve Rogers tells us, is that they’re as obviously close to pure evil as it’s possible to get. The question of whether and when to interfere when the stakes are less obviously Manichean – about how to compromise, to identify those false dilemmas, and to stand by our principles even when they might make us look like moral hypocrites – is at the core of this series and masterfully executed, its profound subtlety hidden in the margins of its Golden Age action. And honestly, it couldn’t come at a better time.

Where to start: Captain America: White #1 Time commitment: four issues

Recommended if you like this: Captain America and Bucky: The Life Story of Bucky Barnes

Add a Comment