[Enjoy this guest post on School of Rock from prior contributor Jessica Lévai. Just in time for Back to School season!]

Claude Lévi-Strauss was a French anthropologist who believed that the myths created and told by a society could be a window into the beliefs and conflicts of that society. A structuralist, Lévi-Strauss saw stories like language and sought to understand their underlying grammar. This he believed centered on pairs of opposite ideas, held by the culture, but creating tension within it — the raw and the cooked, the sacred and the profane, and so on.

Claude Lévi-Strauss was a French anthropologist who believed that the myths created and told by a society could be a window into the beliefs and conflicts of that society. A structuralist, Lévi-Strauss saw stories like language and sought to understand their underlying grammar. This he believed centered on pairs of opposite ideas, held by the culture, but creating tension within it — the raw and the cooked, the sacred and the profane, and so on.

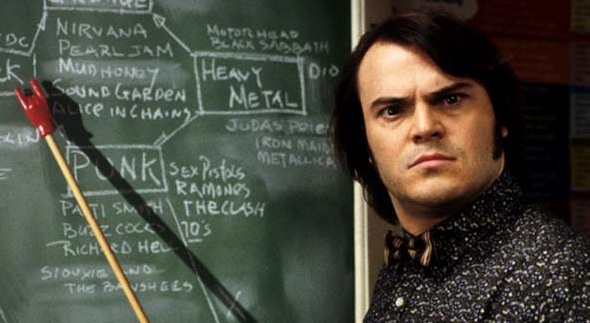

School of Rock, a 2003 film starring Jack Black as slacker Dewey Finn, shows the tension between a truly American pair of opposites: laziness vs. hard work. While in other mythologies it is a trickster character who mediates between these opposites, the nature of this American pair, and the surrounding culture, make it necessary that the trickster not remain so; he has to join one side or the other.

I should begin with the admission that it is technically impossible to perform a Lévi-Straussian analysis on any one film, because there is only one version. Claude Lévi-Strauss sought a rigorous, scientific approach to the interpretation of the meaning of myths. To perform an analysis, he would first collect every version and variant of a myth possible. Each version would be broken down into its constituent plot elements, and these elements plotted on a chart to show how they fit together. The charts would be compared across variants, and eventually the true meaning of the myth would emerge. Any scientist knows that a large data pool is indispensable for getting good results. Unfortunately, there is only one School of Rock.

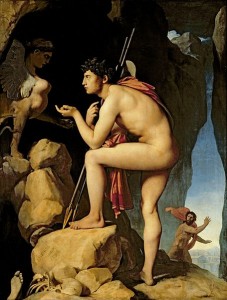

Though we cannot be so thorough as he would have liked, the structuralist principles of a Lévi-Straussian analysis can be applied to the film nevertheless. In his work, “The Structural Study of Myth,” Lévi-Strauss wrote that “the purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction.” Lévi-Strauss concluded that myth provided a way for the ancient Greeks to deal with two complementary ideas, the opposition of which created tension in their lives. His analysis of the myth of Oedipus, for example, discovered two pairs of opposites in tension, and I shall describe one here. Born a prince of Thebes, Oedipus is abandoned to die by his parents, who feared the prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother. This being a myth, it is no surprise that Oedipus eventually does both, if unwittingly. Examining this myth, Lévi-Strauss concluded that there were two opposite ideas in tension here: on the one hand, the undervaluing of blood relations is demonstrated by the patricide, while an overvaluing of blood relations is shown by Oedipus’s incest with his mother, Jocasta. Having failed to negotiate a middle ground between these two ideas, Oedipus ends up blinding himself and retreats to exile.

Though we cannot be so thorough as he would have liked, the structuralist principles of a Lévi-Straussian analysis can be applied to the film nevertheless. In his work, “The Structural Study of Myth,” Lévi-Strauss wrote that “the purpose of myth is to provide a logical model capable of overcoming a contradiction.” Lévi-Strauss concluded that myth provided a way for the ancient Greeks to deal with two complementary ideas, the opposition of which created tension in their lives. His analysis of the myth of Oedipus, for example, discovered two pairs of opposites in tension, and I shall describe one here. Born a prince of Thebes, Oedipus is abandoned to die by his parents, who feared the prophecy that he would kill his father and marry his mother. This being a myth, it is no surprise that Oedipus eventually does both, if unwittingly. Examining this myth, Lévi-Strauss concluded that there were two opposite ideas in tension here: on the one hand, the undervaluing of blood relations is demonstrated by the patricide, while an overvaluing of blood relations is shown by Oedipus’s incest with his mother, Jocasta. Having failed to negotiate a middle ground between these two ideas, Oedipus ends up blinding himself and retreats to exile.

Dewey Finn is a character not unlike Oedipus in that he finds himself in the middle of a contradiction. In the beginning of the movie, Dewey is an unsuccessful rock musician, evicted from the band he created with friends. His lack of success seems related to his lack of real talent, but it is helped by his willingness to use others and general laziness. In his home life he fares no better, as he finds himself threatened with eviction by the roommate, Ned Schneebly, off whom he’s been “mooching for years.” Ned himself has abandoned his dreams of rock stardom for a job: he’s training to become a teacher, and working as a substitute in the meantime. As we look at these two characters, the contradicting pair presents itself. Dewey is lazy but believes in “rockin’.” Ned is hardworking, but dull. This contrast is emphasized with the character of Ned’s girlfriend. She has a 9-to-5 job in government (she works for the mayor) and she hates Dewey, who is the antithesis of everything she stands for.

A ccording to Lévi-Strauss, mediation between a pair of opposites is the function of a trickster. In Native American mythology, Lévi-Strauss reasons, tricksters are cast as carrion feeders like coyotes and ravens, because these creatures mediate between the opposite ideas of hunting and agriculture in that they eat flesh, but do not kill it. One might also consider that scavengers simply mooch off the hard work of predators. A story from the Pacific Northwest tells how Raven learned that all the light in the universe was being hoarded by an old man, who lived alone with his daughter. Raven turns himself into a seed, is swallowed by the daughter, and is born nine months later as the old man’s grandson. Knowing a grandfather can refuse a grandchild nothing, Raven cries and whines until he is given the light to play with. Once he has it, he disappears with it through the chimney and brings it to the world.

ccording to Lévi-Strauss, mediation between a pair of opposites is the function of a trickster. In Native American mythology, Lévi-Strauss reasons, tricksters are cast as carrion feeders like coyotes and ravens, because these creatures mediate between the opposite ideas of hunting and agriculture in that they eat flesh, but do not kill it. One might also consider that scavengers simply mooch off the hard work of predators. A story from the Pacific Northwest tells how Raven learned that all the light in the universe was being hoarded by an old man, who lived alone with his daughter. Raven turns himself into a seed, is swallowed by the daughter, and is born nine months later as the old man’s grandson. Knowing a grandfather can refuse a grandchild nothing, Raven cries and whines until he is given the light to play with. Once he has it, he disappears with it through the chimney and brings it to the world.

Faced with an ultimatum from Ned and desperate for cash, Dewey embraces the trickster archetype. Instead of selling one of his beloved guitars, he accidentally intercepts an offer, intended for his roommate, to substitute teach at a local private elementary school. Dewey steals Ned’s identity and takes the job. This is classic trickster behavior, lying and stealing to get what you want. It doesn’t stop there, of course. Listening to his new charges rehearse in music class gives Dewey a wonderful awful idea: he decides to turn the class into a rock band, so he can use them to compete in a Battle of the Bands contest. He accomplishes this by telling the kids that it’s a school project, and a win would be prestigious.

This begins Dewey the Trickster’s mediation between the extremes of laziness and hard work. To keep his job, he must at least maintain the appearance of teaching a classroom full of elementary students. Much of this is accomplished through tricks such as recording a fake lecture to be played while he and the band ditch school to apply for the contest, or convincing the principal that the music heard next door was really a singing math lesson. On the other hand, Dewey, possibly for the first time in his life, applies himself. He shows up every day to work, and while the traditional reading, writing and ’rithmetic get short shrift, he does show remarkable discipline in teaching his students the fundamentals of rock.

In mythology, a trickster story really only has a few possible endings. The trickster can get away with his scheme, as Raven did when he stole the light. His lovely plumage may have been scorched black by the trip through the chimney, but otherwise there has been no real lesson learned. He has gone through an adventure, changed the world, and still remains Raven, free to make mischief some other day. But a trickster might be punished for his transgression of boundaries, as was Prometheus of Greek myth when the gods chained him to a rock as eagle bait to punish him for his theft of fire. In this case, the lesson is learned, the powers that be remain in charge, and the trickster is neutralized.

In mythology, a trickster story really only has a few possible endings. The trickster can get away with his scheme, as Raven did when he stole the light. His lovely plumage may have been scorched black by the trip through the chimney, but otherwise there has been no real lesson learned. He has gone through an adventure, changed the world, and still remains Raven, free to make mischief some other day. But a trickster might be punished for his transgression of boundaries, as was Prometheus of Greek myth when the gods chained him to a rock as eagle bait to punish him for his theft of fire. In this case, the lesson is learned, the powers that be remain in charge, and the trickster is neutralized.

At first blush, it seems that Dewey’s story follows that of Raven. At first, he is singed when his deception is inevitably brought to light. The police are informed, and Dewey beats a hasty retreat from Parents’ Night at Horace Green Prep, guitar in hand, crash-landing on his friend’s floor, right back where he started. The next day, his students abscond with him to the Battle of the Bands, where they play a “kick-ass show.” While he’s learned to accept his limitations as a performer, Dewey ends the film rockin’, to do so until the day he dies.

But unlike Raven, Dewey does not, in the end, remain a trickster. As the credits roll, we see that he has established a School of Rock in his own apartment (the soundproofing of which is no doubt the stuff of legend), and spends his days happily rocking with the students of Horace Green. It would seem that he has found a way to be who he is and bring in money. But that’s not the case. He is no longer a happy-go-lucky rocker. He has become an entrepreneur. He has started his own business, which means he has entered a world of overhead, taxes, and W-2s. In short, he has gone over to the world of work. He now has a steady job and income. That he gets it by rocking is a pleasant bonus. He loses the trickster qualities of laziness and mooching. Why? Because he must; this is the only ending of the film American audiences will accept.

Unlike Oedipus, Dewey successfully resolves his contradiction, and it is both the nature of the contradiction and the resolution that makes this story so American, just as Lévi-Strauss would have it. Let’s take another look at the pair that drives this story: lazy slackerdom on one side, hard work on the other. In the context of American culture, the trickster has difficulty mediating between the two, because the trickster resides firmly on the side of laziness, which is associated with dishonesty. Since even before Ben Franklin, America has been the seat of the so-called “protestant work ethic.” Hard work is a good thing, and brings just reward. Easy money is to be scorned, as is anyone who does not work hard to earn his keep. With this as a driving philosophy, it’s no surprise that Americans are not comfortable with tricksters. (And after Enron, who can blame us?) Our culture couldn’t tolerate a creature like Raven, at least, not for long. There must be lessons learned, and the trickster has to get with the program or be neutralized. Now that Dewey has been redeemed by his entry to the world of honest work, he no longer represents a threat to the parents at Horace Green or any of the others he successfully deceived, or to the audience of the film. We can let him rock, because he has been domesticated. His school happens after “real” school and is safely separated from it. Prometheus has been bound.

The resolution of School of Rock ably demonstrates that while American filmgoers enjoy watching the machinations of trickster characters, they expect those characters will outgrow their lazy, dishonest behavior. Some of this is, no doubt, due to the fact that this film, if not marketed directly to children, features children and so there is some pressure for it to teach moral lessons.

Jessica Lévai is a professor of mythology and folklore. She’s not related to Lévi-Strauss, but sympathized when she read that people tried to order denim jeans from him until the day he died.

There are a number of movies that fit this archetype. The first I can think of is “Accepted”. The protagonist’s fake college ends up working out and by the end they’ve gained accreditation and become the founders of an actual college.

I haven’t actually crunched the numbers, but I’ll put my neck out and say that it at least feels like most movies follow this archetype. I wonder if that’s one of the reasons that Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is so memorable; on top of being a good film, it ends with Ferris having pulled everything off. Not only does he remain firmly in the laziness camp, but Principal Rooney is punished for his dedication to hard work and integrity, the opposite of the common message.

Huh. As someone who’s never seen that movie, my only real impression of it is all the people on the internet condemning Ferris and defending Principal Rooney on the basis that he’s just doing his job. Probably some significance in that.

I don’t know who all the principal’s defenders are, I just know the cracked.com article. In that case, if I remember the article right, I think Rooney was kind of in there as filler, because IIRC Ghostbusters and the hyenas in The Lion King were much stronger examples of not-actually-wrong villains. (The hyena’s ‘evil scheme’ is, simply, never going hungry again. What REALLY says something is that Disney can make a convincing villain that has THAT as their evil scheme.)

Well, I guess I’m basing it on two internet things. As well as the cracked article, I also saw video dedicated to the subject, and I was putting those together with the commenters who agreed.

This is a really interesting framework for looking at Office Space. Like, if School of Rock (like a whole lotta movies) has to redeem the trickster, and Ferris Bueller doesn’t, in Office Space it’s more complicated.

I enjoyed your L-Sian take on School of Rock. You might find my Levi-Straussian analysis of American television advertising interesting. I had the advantage of having many examples upon which to perform my mythic exploration.

I have also presented a paper comparing Levi-Strauss’s Canonical Formula to Marshall McLuhan’s Laws of the Media Tetrad in which I briefly analyze The Dark Knight. If you like, I will send you a copy.

Best,

Bob Blechman

In Brazilian culture, the trickster – malandro – often has a “happy ending”, but not by getting honest. He just figures a way to be accepted by the system without needing to work.

You should watch Opera do Malandro. Also check this book: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Memoirs_of_a_Police_Sergeant.

Not to mention Macunayma!