[As summer movie season rockets through theaters, enjoy this guest post from Ben Adams! – Ed.]

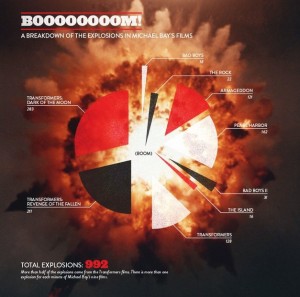

Michael Bay is a maestro of the summer blockbuster. His characters do many things – they blow things up, they run from explosions, they look up at things and they look up at things exploding. Unfortunately, movies can’t be 100% explosion (despite his best efforts), so his characters often find themselves negotiating – whether they are negotiating for a used car or the fate of the world, negotiation is pretty much the closest thing you can get to an explosion when it’s just two people talking.

Bargaining for Advantage

Richard Shell is the Director of the Wharton Executive Negotiation Workshop – effectively making him the Michael Bay of the Negotiation world and making his book Bargaining for Advantage the Transformers. In it, he lays out the foundations for a successful negotiation, and describes the four stages that take place in every kind of bargaining situation:

Negotiation is a dance that moves in four stages or steps. Imagine you are approaching a traffic intersection in your car. You notice that another car is nearing the intersection at the same time. What do you do? Most experienced drivers start by slowing down to assess the situation. Next, they glance toward the other drive to make eye contact, hoping to establish communication with the other person. With eye contact establish, one driver waves his or her hand toward the intersection in the universally recognized “after you” signal. Perhaps both drives wave. After a little hesitation, one driver moves ahead and the other follows.

Note the four step process: preparation (slowing down), information exchange (making eye contact), proposing and concession making (waving your hand), and commitment (driving through). This may seem like a unique case, but anthropologists and other social scientists have observed a similar four-step process at work in situations as diverse as rural African land disputes, British labor negotiations and American business mergers.

These principles hold in all situations – even when everything is exploding around the negotiating parties. We’ll look at these four stages and how they play out in the context of a combustible society.

A Simple Transaction: Bobby Bolivia v. The Witwicky Family

The first situation is probably the type of negotiation that most people are familiar with – buying a used car:

The situation is a simple transaction – the Witwicky’s want to get the best car possible for the least amount of money, Bobby Bolivia wants to sell a car for the most possible profit. Shell discusses two important aspects of preparation (Stage 1) for a negotiation. The first is to match your negotiation style and strategy to the situation at hand. As a man who negotiates all day, every day for a living, used car salesman Bobby Bolivia does this instinctively – he sizes up the situation (a father and son buying a car), and establishes a friendly rapport right from the start, dominating the conversation and claiming to be practically “family.”

Bolivia also performs the other crucial step in preparing for a negotiation – examining the situation from the other side’s point of view. He knows that a high school kid like Sam wants to feel emotionally connected to his car, and knows that the father in this case is probably the final decision making authority – giving him a source of potential leverage. After introducing himself, Bolivia starts on information gathering (Stage 2) right away: “What brings you in?” He learns that the car is going to be Sam’s first, meaning that he may be susceptible to persuasion about the type of car that he will ultimately get.

Sometimes known as “haggling,” proposing and concession making (Stage 3) is what most people think of when they think of negotiation. It’s the stage where the two sides begin throwing out offers and counter-offers. One of the most difficult questions at this stage is who will be the first to put a concrete offer on the table – the old saying is “the person who talks first, loses,” but that’s not always the case. Looking at Bobby Bolivia, he’s the first person to name a price – an excessive $5,000 for a clearly damaged car (that he may or may not, in fact, own). This price, though, anchors the discussion for that or any other car on the lot. The so-called anchoring effect is a powerful one:

In negotiation, research suggests that people who hear high or low numbers as initial starting points are often affected by those numbers an unconsciously adjust their expectation in the direction of the opening number.

We never get to see the result of this anchor, but the surprise from Mr. Witwicky shows that clearly this number was higher than he expected, and may have ultimately gained Bolivia a higher final price. In the event, an unexpected and unlikely explosion changes the closing stage of the negotiation drastically (as one would expect from a Michael Bay movie.)

A Complex Transaction: General Frances X. Hummel, USMC vs. the US Government

Other negotiations are more complex – there may be multiple parties, and many moving parts. Like, say, dozens of hostages and some VX-poison gas tipped rockets aimed at the city of San Francisco:

While more complex, the negotiation between Ed Harris’ General Hummel and the US Government is still fundamentally a transaction – money in exchange for hostages and (unfired) rockets. General Hummel does not acquit himself quite as well as Mr. Bolivia in the preparation phase of negotiation. He matches his style to the situation well – he knows that the Government is likely to doubt the seriousness of his threats, so he goes over the top with his demeanor and his treatment of the White House Chief of Staff. The General, though, clearly hasn’t examined the negotiation through the Government’s point-of-view. He knows the government’s policies inside and out, including, presumably, the stricture that we do not (publicly) negotiate with terrorists. Instead of trying to find a face-saving way of accomplishing his stated goal, he states an inflexible, impossible to meet demand, and practically invites the government to find an alternative to negotiated agreement (in this case, Navy SEALs and thermite plasma).

The information exchange is mostly one way – General Hummel already has most of the information he needs to know about the Federal Government. As a result, his opening conversation is essentially a one sided passage of information in order to establish leverage – the government needs to know that he is serious and that he is in a (supposedly) unassailable situation.

Hummel is also the first to state a concrete demand, but does so in such a way deliberately designed to avoid “haggling” – his sign off of “This is Hummel from Alcatraz, out,” is a way of preventing a counter-offer. Later in the movie, Sean Connery’s John Mason uses a similar move when he destroys the computer chips that Hummel says he wants in exchange for a hostage’s life – by denying the other party the chance to respond or destroying the thing that they want, you can effectively prevent haggling and force the other side into a undesirably either-or proposition.

The negotiation in The Rock never really reaches the “closing” stage of the process – as usual, explosions intervene.

A Partnership: Harry Stamper, et. al, vs. NASA

Not all negotiations are zero-sum transactions. Shell argues that you need to balance the stakes of a given negotiation with the future relationship at stake. In a one-off exchange like a used car sale or a hostage exchange, the stakes are all that really matter – in a long-term partnership, however, negotiators must take into account not only their own short-term interests but the effect that the bargain and the bargaining process itself will have on their future relationships. For instance, if your band of roughneck oil workers has to work hand-in-hand with NASA to destroy an asteroid threatening the world:

Harry Stamper chooses well in his preparation for the negotiation. Because he acts as an agent of the other oil riggers, he’s able to adopt a hesitant, almost apologetic tone – this builds rapport despite the sometimes impossible demands. In keeping with the relationship building nature of the negotiation, Harry Stamper opens with the most important piece of information “They’ll do it.” The so-called “requests” are presented as ancillary concerns. This signals to NASA that the oilmen are interested and willing, but that there’s going to be a price extracted.

Stamper is the first to open with a concrete offer, but does so in a way that is most advantageous to him and his men. He lists the least serious demands first – parking tickets, immigration, a room at the White House, and secures commitment on those issues. He dominates the discussion, and even makes concessions on behalf of NASA (i.e. 8-track tapes). In this way, he appears reasonable and allows NASA to save face, but is able to pick and choose which issues he will get concessions on.

Stamper uses a particularly effect technique to close the deal on taxes known as “foot in the door” – he begins with smaller demands and secures a commitment to those first, in order to get the NASA rep in a position and habit of saying yes. Then he nonchalantly drops the largest demand of them all, and knows he will get agreement on that as well.

The Hidden Step: Exploding Offers

In the context of negotiations, an exploding offer is an offer that has some time limit or other condition, after which it disappears – “I’ll give you $50 for it now, but in 5 minutes I’ll only give you $40.” In the context of a Michael Bay movie, everything is actually exploding, pretty much always. Our negotiators, then, need to be ready to adapt and change their position as events (and explosions) unfold around them.

For a bunch of hardened warriors, General Hummel and his Marines are shockingly bad at this. At the open of the negotiation, General Hummel has 15 poison gas rockets, and his threat to launch is credible – if he launches one to show “he’s serious,” he still has 14 left to go. At the end of the film, however, the Marines are down to one rocket (the rest having been disabled or destroyed). Captain Frye, the crazy Marine who “just wants his money,” kills Hummel and is desperate to fire their last rocket. He’s failed to adapt to his new circumstances – the rocket is his only remaining leverage, and firing it practically guarantees his death (though he has no way of knowing that the F/A-18s are coming to bomb the island no matter what he does).

The negotiation in Armageddon finishes before things start exploding, but the oilmen plan poorly for the prospect of the explosions that are to come. If the mission fails, the negotiation doesn’t matter anyway, so their demands are properly focused on the idea that the mission will succeed – but their “no-tax” demand is pretty much solely dependent on individually surviving the mission, which is far from guaranteed. Only those that survive the mission get any reward at all for it – the families of the dead oil drillers are entitled to nothing.

Bobby Bolivia, on the other hand, reacts surprisingly well to the development that an explosion has destroyed (nearly) every car on his lot. He initially rejected the offer of $4,000 for the Camaro– at that point, he had plenty of less expensive cars than the Camaro that he could possibly for $4,000. After the explosion, however, his leverage is gone – the Witwicky’s can walk away to any other dealer in town, but there’s no way that Bolivia is going to get any new customers with a lot full of ruined cars. The explosion has changed his circumstance – $4,000, in cash, right now, is $4,000 more than he’s going to get later on.

A savvy negotiator needs to be well prepared for all four stages of negotiation. You need to put yourself in the other party’s shoes. You need to understand the importance of rapport and information exchange. You need to be prepared for the other party to open in a way that is advantageous for his side, and be wary of the anchoring effect. You need to be ready to close and be ready to commit. And in the world of Michael Bay, you need to be ready for everything to explode, at pretty much any moment.

Ben Adams is a Naval Officer living in Southern California who should probably be using his time more effectively. When he’s not driving warships or fighting pirates, he (sometimes) maintains a blog.

How has no one commented on this yet?

Ben, thank you very much for this article; the book by Shell went straight to my Amazon wishlist – I love me some applied social psychology / game theory.

The important role that face-saving plays in a successful negotiation has fascinated me before in some real-life situations, and I’m glad that I now have your example from The Rock to explain it to people.

Looking forward to your next post :-)

Yeah, that was pretty damn awesome. I’m sure using these tips at work.