[While we’re on the subject of superhero movies, enjoy this deep read of Thor by Hailey Bachrach! – Ed.]

The thing that had me most excited for 2011’s Thor was not my familiarity with the comic (I had none), or even the prospect of seeing Chris Hemsworth’s gorgeous biceps (though it’s a definite plus). I was psyched because I’d heard it was directed by Kenneth Branagh. I, and I think most people, know Kenneth Branagh for his film adaptations of Shakespeare.

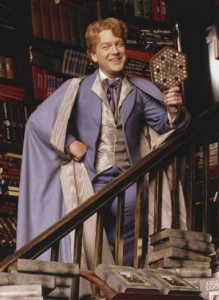

Except for those who know him as Gilderoy Lockhart.

In his film acting/directing debut Henry V, he was nominated for best actor and best director. He also directed and starred in critically acclaimed adaptations of Much Ado About Nothing and Hamlet. Thor may seem like a dramatic departure from his usual fare. But in fact, in directing the origin story of the Mighty Thor, Branagh was also adapting the origin story of his first film, Henry V.

Henry V tells the story of King Henry V’s war to claim French territories. The English triumph against impossible odds, Henry makes a famous speech, and in the end he wins the battle and the hand of the French princess.

Henry V is actually the fourth part in a series of plays which depict the reigns Henry V and his father, Henry IV. The future Henry V first appears in Henry IV Part One as Prince Hal, the heir to the throne who spends most of his time picking pockets and getting drunk with thieves in London taverns.

In contrast, Shakespeare offers another Henry: Henry Percy, called Hotspur. He has already made his name as a fabulous warrior, and the King openly wishes that he and Hotspur’s father could swap sons, because Hotspur is clearly better suited to kingship than Hal. But Hotspur is also an idealist, and he is disgusted with the corruption of the court, and spearheads a rebellion against the crown.

Hotspur embodies antiquated notions of chivalry and militaristic honor. Hal, on the other hand, is of a breed we find more familiar today: a politician, a thinker, who does not win his battles with brute force, but with strategy. Even his dissolute behavior is, as he informs the audience, only a show to win the loyalty of the people by appearing to undergo a dramatic reformation. The culmination of this plan is a dramatic encounter with his father, where he vows to redeem himself by defeating Hotspur.

This may sound familiar. Hal is one of a long line of Shakespearean characters who act as the playwrights of their own lives, manipulating other characters into playing out scenes for their own advantage. Loki fits neatly into this pattern. Just as Hal puts on an act of drunken indifference in order to impress his father with a sudden show of strength, Loki very carefully crafts a murder attempt so that he can sweep in and save the day, thereby winning his father’s esteem. Each recognizes the political and emotional importance of grand gestures, and are too smart to leave their opportunity to perform such a gesture to chance.

Thor and Hotspur also love gestures, but theirs are spontaneous and focused in the glory of battle. Thor risks everything to attack Yodenheim in revenge. Hotspur likewise pins all his hopes on the Battle of Shrewsbury, where he, like Thor, is hopelessly outnumbered and presses on only out of a true love of combat and hunger for glory.

When Hal finally kills Hotspur, it is far from a moment of unadulterated triumph. Hotspur dies stunned by the realization that he really is only human and Hal eulogizes him beautifully, with a painful recognition that while Hotspur would not have been a good ruler, the passing of his brand of idealism and courage is a profound and permanent loss to the world.

The metaphorical death of Thor in the form of his banishment causes Loki no such pain, and Thor receives the second chance that Hotspur does not, He learns to temper his violence and lust for glory and returns to make good. But his and Loki’s final battle still parallels that of Hal and Hotspur. Loki is desperate to prove himself and to win not only for the sake of victory, but as symbolic evidence of his own triumph over his past; and Thor, though more moderate than before, still treats battle as a question of purely physical domination (he will not fight Loki because he does not wish to hurt him, unaware that his refusal to engage is a much more profound loss on the metaphorical level on which Loki is operating) and is ultimately unable to resist the urge to make a spontaneous and glorious final sacrifice.

In the world of Thor, Hal dies (or, rather, tumbles into a vortex to return in summer 2012…) and Hotspur is triumphant. Kingship of the mind is subjugated to kingship of the sword. Shakespeare told a compelling story of the exchange of martial, glory-hungry kingship for one focused on strategy and performance. Over 400 years later, Thor reverses the roles once more. Henry V outmaneuvered his enemies and conquered France (historically, a victory fueled not by inspirational speeches, but by the strategic advantage of English longbows against French cavalry). Does Thor’s victory have an equally positive prognosis?

There are two answers to this question, for the two levels on which this film exists: as a 2011 summer blockbuster about a superhero named Thor, and as the spiritual prequel to Branagh’s Henry V. I say “spiritual prequel” because obviously in terms of literal subject matter, the two films are unrelated. But thematically and, as discussed, in terms of Shakespearean parallels, they are intimately conntected. In this latter sense, the ending of Thor is a perfect set up to Branagh’s Henry V.

Though set in medieval England, the film of Henry V is a post-Vietnam vision of warfare. One of the most powerful scenes is a beautiful but haunting sequence about burying the thousands of casualties of the recent battle. War in itself is not simple or glorious or possibly even worth it, but the soldier-king of England has led them into it. Looking at the tetralogy as a whole, we learn in Henry IV Part Two (the play that immediately precedes Henry V) that Hal plans to invade France upon assuming the throne in order to consolidate power and focus the energies of various potential factions on a common enemy: a perfectly political, Loki-esque goal. But taken as a film in isolation, no mention of this is made in Henry V. We jump over the politicking, and so see only Henry’s yearning for the glory attendant on conquering France. It is not a world where Loki schemes, but where Thor fights. And perhaps the ends justify the means, but Branagh’s Henry V reveals that when warriors are king, said ends are a long and rocky road.

There’s also a lot of mud.

But what does this ending mean for Thor itself? Especially in America, we are living in a time when the politics of idealism are particularly potent. Hope and change won an election, though now many say President Obama’s term has been characterized by a growing disillusionment . In Henry IV Part One, Hotspur’s motto is “Esperance”—that is, hope. Idealism is antithetical to the Prince Hal/Loki school of politics, whereas Thor and Hotspur are defined by it. A large part of the disappointment with Obama has been the realization that his White House runs not on hope and change, but on the same scheming and negotiating as everyone else. The victory of Thor over Loki is recognition that we long to be ruled by the idealistic. But as with Hotspur and even as with Obama, when faced with the practical realities of governing, those hopes are destined to be dashed. Idealism sometimes raises armies, but it cannot raises taxes or negotiate treaties.

But Thor exists in a different world. He is a superhero and a god. His father is essentially immortal. Thor can maintain his idealism, because it need never travel outside the very superheroic context of physical prowess and into the thornier realm of government. His is, in fact, the only context in which idealism can wield power and still remain pure.

Henry’s is a dirtier world. He is a mortal in a line of mortal kings—he must succeed his father, and will be succeeded in turn by his son (that part doesn’t go so well). Hotspur would have gone far in Thor’s fantasy world (and he already has an awesome superhero name), but reality demands the ruthless practicality for which Loki is far better suited. Thor is the idyll: Henry V is where those dreams meet reality.

But, in the end, it’s hard to be completely cynical when you’re faced with speeches as rousing as this:

Wait, isn’t that–?

Hailey is a graduate student and aspiring professional overthinker of Shakespeare.

Few remember that Loki actually killed Thor via the Destroyer in the film. So in following your Loki=Hal Thor=Hotspur logic you could argue that the film also followed along the lines of the play, where Hal killed Hotspur and gained the throne for an instant before Thor came back to life.

Very good article, particularly the thought about the superhero ideal versus Henry V’s muddy pragmatism. One minor point though; the politicking isn’t completely jumped over in the play (or the film). The scene near the start with the (intentionally?) dull and confusing discussion of land rights and inheriance gives a justification that, interestingly, is neither pragmatically political nor based on glory and honour, but instead driven by obscure legalities.

Holy superhero siting, Batman! That’s totally Christian Bale in the crowd, there.

One of my favorite renditions of this speech:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=luqr-UX_oSM

Nice work. I’d also add (or maybe emphasize more) how Odin preferred Thor first, as King Henry IV would have rather given the crown to Hal at first. That kind of exacerbates the difference between the “reality” of the historical play/adaptation and the fiction of the superhero world in the Marvel movie.

I really want to hear that speech in the original Klingon.