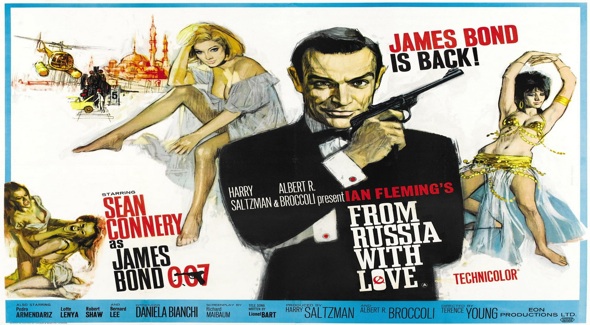

Matt Zoller Seitz, one of my favorite film critics, recapped a recent revival of From Russia with Love, the second film in the James Bond series. It hasn’t aged well, Seitz admits, but that didn’t excuse the audience’s behavior:

I heard constant tittering and guffawing, all with the same message: “Can you believe people once thought this film was daring? It’s so old-fashioned.” The arch double-entendres; the bloodless violence, long takes, and longer scenes; the alpha male attitudes toward women and sex; John Barry’s jazzy, brassy, borderline-hysterical score: all these things elicited gentle mockery. They laughed at Sean Connery’s hairy chest. They laughed at some obvious stunt-double work. When Bond flirted with the secretary Moneypenny and put his face close to hers, a guy a couple of rows in front of me stage-whispered to his friend, “Sexual harassment!”

[…]

I hate to be the guy who says “You’re watching it wrong,” but these people definitely were.There might be a lot of factors contributing to the viewers’ failure to engage (surely including lack of film literacy), but ultimately, that’s their decision and their loss.

It’s up to the individual viewer to decide to connect or not connect with a creative work. By “connect,” I mean connect emotionally and imaginatively—giving yourself to the movie for as long as you can, and trying to see the world through its eyes and feel things on its wavelength.

Like I said, Seitz is one of my favorite critics. I trust his insight on films and TV shows. Which is why it pains me to say he’s off base here.

Training Is Useful, But There Is No Substitute For Experience

Every film, like every work of art, is a product of its time. It arises from the cultural influences of the artists who created it and the cultural expectations of the audience it was made for at the time. When we speak of a “timeless film,” we mean films where the main elements – plot, performances, composition – translate well outside of their original generation. Or perhaps elements that shift in meaning but still work in a new context. Consider Hitchcock’s innuendoes: edgy at the time, cheeky today, different reactions but still effective. Regardless, no film, short of the completely abstract, can be truly timeless.

Seitz admits as much, albeit reluctantly. “For a good many people, movies aren’t art or experience, they’re product,” he writes. “And products date.” Considering what he thinks of “many people” throughout the rest of the article, it’s fair to assume that he doesn’t put a lot of weight on the tendency of films to age. We’ll get back to this difference between experience and product later, but it’s something to note now. While Seitz acknowledges that a film is a product of its time, that shouldn’t detract from its experience.

But the experience of a film is comprised of two variables: the film itself, and the audience watching it. And just as a film is what time and circumstance make it, so are the people watching it. We pride ourselves on being free-willed, intelligent consumers, but the choices we make, free as they are, can only be among the choices made available to us. Liking Stephen Soderbergh more than Michael Bay might indicate a preference for studied cinematography, but odds are you never heard of Soderbergh until he got some real money behind him (George Clooney, Jennifer Lopez, 1998’s Out of Sight). And if you did, congratulations – that means you’re an arthouse cinema regular, and your film tastes are a result of whatever your local indie theater had in its rotation.

So we have the film, a product of its time. And we have the audience, a product of its time. If those two contexts are different, there’s a disconnect between where the film comes from and where the audience is willing to meet it. Again, this is something Seitz admits – he gets why one audience member would whisper “Sexual harassment!” to another when watching Bond flirt with Moneypenny; it’s not a complete non sequitur to him – but I don’t know that he gives it enough credit.

So far, the unexceptional stuff. Now here’s where we go out on a limb.

Give a Wolf a Taste and Then Leave Him Hungry

In the era of digital social media, producers make a lot of the additional features that attach to a piece of content. DVDs come with commentary tracks and making-of featurettes; ebooks come with questions for book clubs or class discussion in the back; articles are footnoted with icons indicating how many times they were shared, liked or pinned. The thing in itself is no longer sufficient, we’re told – it all needs to be placed in a greater context.

While this is true, this doesn’t take away from an artist’s responsibility to create a work that stands on its own. A great piece of art can be made more interesting by knowing its context: knowing that From Russia with Love is Desmond Llewellyn’s first appearance as “Q,” but not under that name, for instance. But a good piece of art won’t be made better, nor a bad piece of art good. Learning that Glitter hit theaters the week after September 11th is useful trivia, but doesn’t make the slop more palatable.

The experiences on which a film should be judged have to take place between the first and last frame. To expect anything else shifts the burden of storytelling from the director, the actors, the editors, the set designers, etc., onto the professors, film critics and pundits who discuss the piece. Knowing that From Russia with Love was Pedro Armendariz’s last film gives his performance a touching bit of poignance, particularly certain lines: “I’ve had a particularly fascinating life. Would you like to hear about it?” But Armendariz’s performance, as the gregarious Kerim Bey, has to rise or fall on its merits. (How many other actors have gone out on a real turkey?)

Anything beyond the level of mere experience activates the critical mindset, or the desire to overthink.

This isn’t to say that the critical mindset has no place in the experience of pop culture. But the consumption of pop culture and the subjecting of that culture to a level of scrutiny it probably doesn’t deserve are two distinct acts. One is observational; one is infiltrational. The former is passive; the latter, active. Overthinking a work of pop culture enhances the viewing experience, but it can never be a requirement. If it is required, it’s not truly “pop.”

Go On About the Mechanism

With that, let’s get back to Seitz’s piece.

Seitz watches the revival of From Russia with Love in a “small but packed Manhattan theater.” It’s not for a film class – it’s paying customers in a commercial auditorium. We can’t say for sure, but the context suggests that most of the audience, particularly the titterers, were not intimately familiar with From Russia with Love going in. This isn’t surprising. Though considered by some critics to be the best Connery Bond, it lacks the style of Goldfinger, the audacity of Thunderball or the sheer goofy spectacle of Diamonds Are Forever (personally, I’d put it beneath all of those, but I’m only one man).

As such, it’s safe to bet that this was the first time many of the audience had seen this movie, or at least the first time in many years. So why see it?

James Bond, as a cultural icon, transcends the performance of any one actor. He’s as much the sexy Connery as he is the arch Moore, the cold Dalton, the suave Brosnan, the brutal Craig, or, yes, even the sardonic Lazenby. When we fall in love with Bond, though, we fall in love with one of those portrayals in particular. It’s tough to imagine a fan of You Only Live Twice responding to Octopussy with equal enthusiasm, or a fan of the fantasia that is Live and Let Die responding as warmly to the gritty naturalism of Craig’s Casino Royale. And not even every performance within an actor’s tenure can be compared: the rigorous plotting of For Your Eyes Only vs. the sci-fi stunts of Moonraker, both Moores.

So you had a theater full of people, some of whom had probably seen Dr. No as a kid and who remembered Sean Connery fondly. But they clearly didn’t know what to expect. They showed up, were surprised at how poorly the material had aged, and reacted the way smart and insecure people do to surprise: by joking about it. This is normal.

(Granted, anyone who talks loudly enough to be heard in a movie theater has forfeited their right for humane consideration. But Seitz’s complaint isn’t about the disruption as such, but about the attitude that provokes it)

“It’s up to the individual viewer to decide to connect or not connect with a creative work,” Seitz says. “By “connect,” I mean connect emotionally and imaginatively—giving yourself to the movie for as long as you can, and trying to see the world through its eyes and feel things on its wavelength.” Well, okay, but it’s also up to the movie to connect with the audience, by providing lines, images and scenes that will last beyond a few years. Nobody snickers through Casablanca, a movie that’s twenty years older than From Russia with Love. Though I did see it in a theater once where Ilsa’s line “Is that cannons, or the beating of my heart?” produced laughs, but I would be shocked if that line didn’t produce laughs in 1942.

Seitz, a critic, was trapped in a theater full of people who were viewing the movie with a non-critical mindset. They were experiencing it. Seitz’s friend chastises the audience for “not experiencing the movie,” but I would argue it’s Seitz who’s taken out of the moment by imagining himself seeing this movie on a date in 1963, not actually seeing it in 2012. He’s constructing a narrative in his head, in parallel with Terence Young’s efforts to construct a narrative onscreen, in order to let the narrative onscreen engender the feelings in him that it would a man of his age in 1963. If you went to a performance of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and imagined that you were Hector Berlioz himself, performing it for the first time for Harriet Smithson in 1832, you’ve certainly had an interesting experience. But I’d be hard-pressed to say you had a richer experience than someone who just sat there and enjoyed the music, and I couldn’t swallow the idea that anyone who wasn’t doing what you did was doing it wrong.

Actually, it’s odder than that – Seitz is constructing a narrative in his head in order to let the narrative onscreen engender the feelings in him that he thinks a man of his age would feel in 1963. We have little way of knowing how an audience member of 1963 would view a Bond movie. The critics of the time called it “fun” and an “adventure,” but they also called out its “self-mocking flamboyance” and “nonsense.”

So even presuming it’s possible to create an accurate mental image of a filmgoer in 1963, we don’t know whether that Platonic ideal would have even liked From Russia with Love. Our hypothetical male might have found the scene where Bond beckons two feuding gypsy women to his tent with a wordless gesture as ridiculous as Seitz’s neighbors doubtless found it.

Seitz portrays this as a more vulnerable posture – “giving yourself to the movie” – but it’s actually far more defensive. He has to construct an elaborate mental scenario in order to find the film stimulating. He has to armor himself in the clothing of a fictional 1963 male in order to have a satisfying experience with the film. It’s the other audience members, laughing reflexively, who have their guards down.

To reach the point I’ve been working to for some time: Seitz is overthinking From Russia with Love. That’s fine. I and the other writers on this site would say that it’s a worthy pastime. It enriches your viewing experience of any movie. But it’s not a requirement. Overthinking subjects pop culture to a level of scrutiny it probably doesn’t deserve. It’s the next level of consumption, not the first. It’s the post-movie conversation over drinks, or the talk with a stranger on the train, or the essay in your film studies class. It’s post-event, not pre- or intra-event.

We love overthinking artifacts of the popular culture, and we’re happy to consider Seitz one of our fold. But we can’t endorse his position that failure to overthink is “doing it wrong.”

It’s like “The Birth of a Nation.”

(How many other actors have gone out on a real turkey?)

Raul Julia, “Street Fighter”.

Jimmy Stewart, _An American Tail: Fievel Goes West_

George C Scott, The Exorcist 3 (He even got nominated for a Razzie!)

Immediately after reading this article, I started reading an essay for class. Within the first paragraph, I came across this:

“Men, it has been said, may be divided into two classes: those who don’t know what is Art but know what they like, and those who don’t know what they like but profess to know what is Art.”

I don’t really have anything to add, other than the fact that Goldfinger > X, where X = any other Bond Movie.

Seitz’s comments reminded me of this great Jonathan Lethem essay, “Defending the searchers,” all about his frustration in watching the movie with other people, trying to get them to look past the crazy racism and get into the themes of the film. At the end, he sorta realizes that the film doesn’t NEED him as a defender, that the impulse to do so is largely egotism:

“Detractors of The Searchers are casual snipers, not dedicated enemies – they take a potshot and wander off, interest evaporated. Those who care like I do cherish their own interpretations, they don’t need mine.”

I went to a screening of Psycho with the music played live by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra.

There were odd moments where people tended to laugh or titter and there was a woman next to me who was acting almost morally offended that anyone would ever laugh at a Hithcock movie.

The thing was, alot of the laughter was very nervous laughter. People might snicker at certain lines, or a somewhat odd sounding dubbed in yell of a man being pushed down the stairs, but it was only during or immediately extremely tense and uncomfortable scenes. People weren’t laughing because the film was ineffective in a modern context, they were laughing because how much the film DID affect them.

Also though, some lines have just entered into public consciousness and now just have a different effect in the context of the film due to foreknowledge. “A Mother is a boys best friend” for instance.

“A boy’s best friend is his mother.”

indeed. Thanks.

People might snicker at certain lines, or a somewhat odd sounding dubbed in yell of a man being pushed down the stairs, but it was only during or immediately extremely tense and uncomfortable scenes. People weren’t laughing because the film was ineffective in a modern context, they were laughing because how much the film DID affect them.

This is a good point. I had a similar reaction to a scene in Saving Private Ryan, when a GI gets blown up by his own “sticky bomb” in the final tank battle. I was so startled by it I said, “Whup!” aloud, which prompted a few nervous giggles from people around me. But I wasn’t trying to be a smartass – I was startled enough that I just said the first thing that came to mind.

All this said: Seitz was in the theater with these people and I wasn’t, so I shouldn’t presume whether their laughter was reflexive or a posture. However, it’s a broader context to keep in mind: not all laughter is a form of conscious disdain or remove.

This line of thinking is why Bloodsport is a comedy, along with other similar supposedly bad films that became cults of the “that’s ridiculous” kind. Some films become more lasting by becoming comedies that lampoon genres or historical traditions and trends.

Out on a turkey:

Gene Hackman retired after “Welcome to Mooseport”.

Matthau’s last movie was “Hanging Up”

There are many, many others I’m sure….

This is just another example that was brought up in the Gangnam Style post. Are these people “bad” or is it an indication that the movie has acquired a different audience. Mores change. Railing against *your* interpretation is like yelling at the tides.

/CSB I was fortunate to see a roadshow release of Manchurian Candidate after prints were sent around to theatres after Frank died. Great flick but there’s the scene where Frank and Laurence Harvey are sitting in his living room and his wife interrupts. Harvey sends her back with the admonishment to “go back into the kitchen and do wifey things”. The whole theatre sucked in their breath at that and there was a distinct pause. That line probably didn’t raise an eyebrow in 1963 but 25 years later wouldn’t pass muster. Things change. /CSB

To be entirely honest, with the possible exception of Dr. No, nearly all of the pre-Craig Bond movies has been a little tongue-in-cheek. The Daniel Craig saga is less classic Bond and more sleek, re-vamped Bond. To me what makes FRWL good is that it honestly tries to create a slightly outlandish espionage-action thriller without resorting to the completely commercialized Goldfinger or Thunderball. I remember sitting in a theater watching “Tomorrow Never Dies” a tremendously horrible Bond movie, and the audience was having the same reactions to a movie in 1998 that Seitz’s audience had today watching a film from 1963.

I can be certain that I don’t view any Bond movie with anything other than my experience at the time. Tomorrow Never Dies is my favourite, regardless of any intrinsic quality, because it was the one I experienced when Bond’s level fit with my level.

The only other one I really love is The Man With Golden Gun but that is very much because it hasn’t aged well at all. Its prejudices are so unacceptable to be safely laughable.

I’m always going to love Goldeneye the most, because it was the first Bond I ever saw in the theater, and it was pretty awesome.

That was the first Bond I saw period, so I’m with you, there.

I’m also pretty uncomfortable with the notion, only loosely touched on in this article (and the Lethem one above) that commenting on the sexism or racism in old movies is missing the point. Trying to force veneration on an audience that doesn’t feel it is not only counterproductive and hegemonic, but it also stops us from seeing and discussing flaws in the original that were perhaps not so visible at the time.

(And it’s really weird that Seitz is making this case for a James Bond film, which was never meant to be a deep artistic statement. You can make the case that, say, Metropolis, should be appreciated despite its dated elements, but if a dumb action movie is no longer enjoyable without thinking then it’s about as useless as a film can be.)

Rob brings up a point I was going to, and allow me to elaborate more on how I was going to put it. Because I think it’s quite possible to view a movie through multiple lenses at once. Going off of the two levels of viewership you mention, John, I think it’s not all that difficult to both consume and overthink a movie at the same time. So, the sexism and racism can be consumed and thus chuckled at or accepted as well as criticized and pointed out as insensitive at best, flat-out oppressive or hegemonic (to use Rob’s diction) at worst. And keeping the original context in mind allows for both “types” of viewing.

I find this works with about anything, contemporary or not. Take John Locke. Dude writes about freedom and the right for any man to own property, etc. And at the time, holy crap! Somewhat revolutionary? Sure. Of course, we know what he really meant was white men, and that he was living in a time where it was totally normal to have disdain for tribes in North America for not using land “properly” and whatnot. That doesn’t make Second Treatise (or any of his other writings) less valuable today, it means we apply his standards more broadly and interpret their meaning differently than someone back then would have. It doesn’t make his writing horrible in meaning per se, tough. In order to apply that standard differently, though, we first have to understand its original limitations.

So anyway, to bring this back to pop culture and out of political theory (sorry), what I’m saying is it’s often valuable to think in more than one way about the same piece of pop culture. You can bob your head to the beat and smile to a Taylor Swift song, while also realizing a lot of her lyrics play into gendered (Chrome, why do you not recognize “gendered” as a word???) stereotypes and the old-fashioned, damsel in distress trope. Enjoying it doesn’t mean you condone any hegemonic paradigms. You can appreciate the movie or item being consumed and still question any status-quo messages that get presented within it.

I may have just totally restated the point of your article, but I dunno.