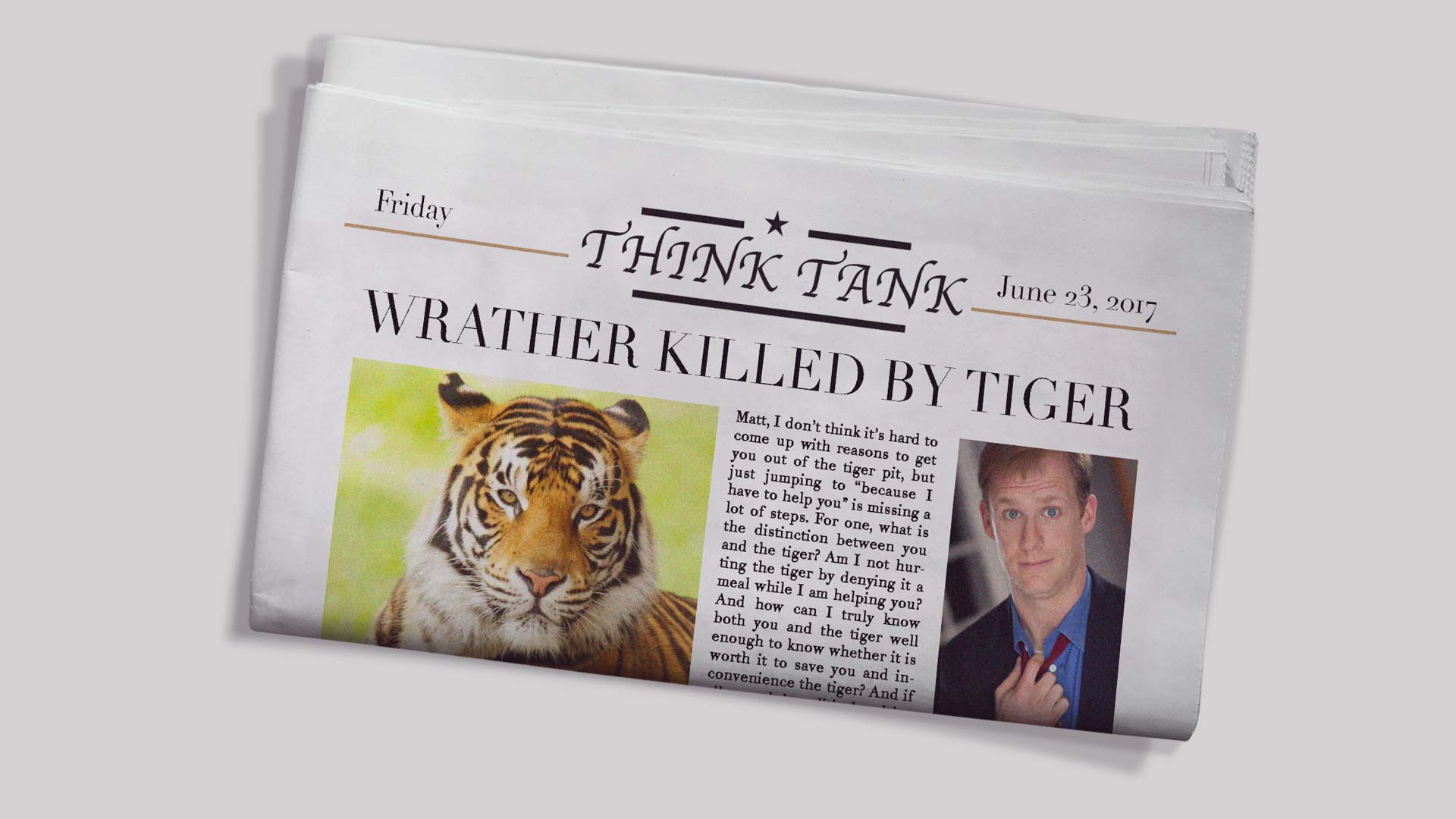

In Part 1, the ethics of abstaining from the news somehow turned into a discussion of whether one is obliged to rescue Matt Wrather from a tiger pit. It’s not as clear-cut as you might think!

Pete Fenzel: Matt, I don’t think it’s hard to come up with reasons to get you out of the tiger pit, but just jumping to “because I have to help you” is missing a lot of steps. For one, what is the distinction between you and the tiger? Am I not hurting the tiger by denying it a meal while I am helping you? And how can I truly know both you and the tiger well enough to know whether it is worth it to save you and inconvenience the tiger? And if all speech is political and interested, how can I trust the information I have about you and about tigers? What about other people who might breathe your air or eat your food or live in your apartment? Maybe I should just jump in the tiger pit with you, strangle you, and feed myself to the tiger. What about the liebensraum we might provide to other people? Have we decided already that there is no broad historical justification for why one tribe of people should live and another die? What if there is a superior master race — either in quality or in right — that ought to supplant us and rule the planet in the spirit of authentic existence of the weak and the strong?

That escalated quickly.

But also, if people only ever do things because they bring some form of pleasure or behavioral incentive, what is the point of a concept of obligation? Should we instead be talking about what I expect to get out of helping you and why that makes it a good deal?

I’m not saying these are the answer, but we have to rule them out to accept this premise.

Matt Wrather: (shouts “tell my storyyyyyy” out of the tiger’s closing mouth)

Fenzel: Just to start it out more constructively, what is the basis for this obligation to help people? Is it right and wrong? Is it aggregate pleasure maximization? Is it tradition? Is it the Golden Rule? Is it material dialectic?

One common argument is that you have an obligation to be informed that is contingent on living in a republic and being a voter. It’s part of your role in this institution to participate in, and it has both reasons and consequences associated with it. But that’s a much narrower idea than the idea that you have to help people if you can, and it is vulnerable to the default by the institution on its own obligations to you. If the republic does not serve your interests in the way it’s supposed to, voting, and thus staying informed, start seeming arbitrary.

Richard Rosenbaum: I can see the moral utility of making oneself aware of what’s going on inside of one’s own “moral community” (i.e. those people whom it is within your direct power to help), and that scope is going to increase as your psychological and economic resources increase. As citizens of western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic nations, that number should be larger for us than the number of people in less privileged situations than we are (in principle).

BUT we also have to take into account that being equally aware of the horrors going on in, say, Syria or Chechnya (or, you know, England) does not magnify our capacity to be of moral use to those people despite our vast resources relative to the people who might only know that a suicide bomber just blew up the pizzeria on the corner but who is in a position to physically rescue someone caught in the explosion.

That person is going to have WAY more PTSD than us sitting on our leather couches hearing about it on CNN. But the accumulation of knowledge about just how completely fucked we all are (ISIS, climate change, Roger Waters’ new album) is almost certain to take up so much of our cognitive resources that we become morally paralyzed.

All and all it’s just another brick in the wall.

At least that is what I felt was happening to me, when I made the decision to disengage, primarily from social media but also from the news cycle generally.

So Pete, to answer your question about the basis of our obligation to help people, I’m gonna go with the Categorical Imperative: people are ends in themselves, not just means to your ends. That obligates us to help when possible.

Fenzel: Sure, that’s one way to go about it, but I don’t think it’s uncontroversial either. A lot of people would have problems with the idea that there is intrinsic worth to being a rational agent that does not belong to those who are not rational agents, because it gives people the moral authority to eat meat, and a lot of people have a problem with that.

It also requires you to be honest even with people you oppose, and a lot of people have a moral problem with that, too. And it requires respect for law as a concept, and a lot of people have a problem with that, too. Some people likely have a problem with assuming a German ethical system should be privileged on its “merits” as if white men have default access to truth.

I mean, I’m fine with this sort of approach in my own life, but if we choose “categorical imperative” as the basis for why we help people, we should be honest about what we are doing rather than assuming it is the way to go by default. The categorical imperative requires us to do that much, I think.

Rosenbaum: A lot of people having problems with it doesn’t invalidate it. Morality isn’t democratic — unless it is, in which case there isn’t any reason to help anyone really. If moral responsibility isn’t contingent on rationality then it’s equally wrong for Matt Wrather to eat meat as it is for that tiger to have eaten him. But I don’t think that even Peter Singer would say that the tiger has any moral obligation not to eat Matt. Basically moral relativism is incoherent and Kant’s formulation of a rational basis for morality isn’t any more A White Guy Telling Us What To Do than, say, calculus is.

“Out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing can ever be made, only delicious tiger food.” – this guy, probably

Wrather: Pete, are you sandbagging for fun or for profit? Like, when I say “uncontroversial” I mean “uncontroversial among my right-thinking bros.” Obvi.

Rosenbaum: “Uncontroversial among non-monsters.”

Wrather: The Woketatorship may see no problem with throwing out the Enlightenment because anything a white dude says is tainted, but I’m not so eager.

Anyway. My finger is still on the remote. Do I turn on the News Hour or not?!

Rosenbaum: Omg the Woketatorship. That is perfect. Anyway, DON’T DO IT MATTHEW! IT ISN’T WORTH IT!

Fenzel: Here’s what I think: I think it is advantageous for you to be informed, it is good to be informed, it is helpful to be informed, but it is not an obligation except contingently as a consequence of making other promises or commitments, in much the same way that it is good to help people and advantageous to help people, but not something you, realistically, have to do.

It is not very useful to treat moral wrongs as lapsed obligations for their own sake, even if it is rational, because that brings with it either the delusion that you can and ought to compel other people into obedience (which is itself a rational moral wrong), or to acceptance of an irreconcilable gap between your description of the world and your experience of it.

If Matt is in the tiger pit and I find out that I can save him, and I do, that’s good! But if his attitude is neutral, like I saved him out of obligation rather than thanking me for my help, I might throw him back in.

And if everybody I know all decides to stay informed of the tiger pits so we help each other, that’s great! Everyone will be happier, everyone will be more virtuous, we will set a good example to others, it’s all upside.

But if half my neighbors refuse to get involved, there’s little real value in my saying “But you HAVE to!” unless there’s some legitimate basis for my authority, some other contingent factor (like the law) or I expect it to accomplish something.

It’s also the distinction between positive and negative rights in play. I have a real problem with people who refuse to distinguish between positive and negative rights.

You have a negative right for me to not push you into the tiger pit, sure. But you don’t have a positive right to compel me to get you out and you fall in yourself. So it’s fair for me to get paid to do it if that turns out to be the best way to handle it, rather than through obligation.

So, should you turn on the TV? If the reason to do it is because of the good of it rather than the obligation of it, then you can start to actually weigh the good and the bad and make a real life choice.

Wrather: Second time I’ve gotten eaten today.

Next time: world news vs. local news, and the limits of our obligations to society.

@Fenzel, I have new found respect for you.

Sometimes you drive me crazy. I was right there with @Wrather when he said, “Pete, are you sandbagging for fun or for profit?”

Like seriously, sometimes your assertions drive me bananas. I know this is OVERTHINKING IT, but damn man.

But now I think I get it. Your final summation is a coherent, pragmatic response founded on seemingly realistic constraints to a strong philosophical root. The whole crazy postmodern relativism thing was not only for kicks and giggles, but an actual attempt to critically think the issue, and run through the various alternative perspectives present in our modern world. I try to do this as well, but I don’t think I am as good at it as you. You give me hope for the critical thinking possible out there in the wild, and the ability to rein it back in to try and come up with a real world answer.

So thank you, to all of you!

BTW, @Wrather, best head shot pairing in the header!