Matt Belinkie: So guys, I recently started watching You’re the Worst, an FX comedy about two horrible people falling in love. We meet the guy at the wedding of his ex, where he’s using all the disposable cameras to take pictures of his junk. He meets her in the parking lot after getting kicked out, where she’s in the process of stealing one of the wedding gifts. A lot of the humor comes from the two of them doing various inappropriate things (borrowing a friend’s military uniform to skip the line at brunch, stealing a cat, child endangerment).

This got me thinking about whether comedy can be broken into two broad categories: stories about people trying to be good and play by the rules, and stories about people flaunting the rules, where the fun comes in seeing how far they will go. To invoke the two giants of 90s comedy, Seinfeld is about selfish, amoral people, and Friends is about nice, caring people. Cosby Show is Nice. Married With Children is Naughty.

Mark Lee: Naughty shows: Simpsons, Family Guy, South Park

Nice shows: Parks & Rec, Frasier (I think), Modern Family

30 Rock breaks the mold, I think. Both Liz and Jack alternate between selfish and charitable acts in their own ways.

Belinkie: Hold on Mark, I think some of those are debatable. The Simpsons doesn’t really seem like a Naughty show to me, or at least not all the time. Marge and Lisa aren’t Naughty, Homer and Bart are. Let me propose an alternate definition – in a Nice show, the main characters are the straight men. They’re trying to do the “normal” thing and the world keeps throwing them into funny situations. Whereas in a Naughty show, the main characters are monkey wrenches that are taking on the world. So for instance, in Arrested Development Michael Bluth is Nice, and everyone else is Naughty.

Jordan Stokes: Or rather: Michael thinks he’s nice, and tries to be nice. Deep down, he’s as bad as the rest of them.

Belinkie: Is he? I’d say deep down he’s a big pussycat. But maybe we need to sharpen the definitions here. A lot of sitcoms are about good people who end up doing misguided things for 24 minutes, then apologize for it at the very end.

Now it might be that on closer inspection, even my “Naughty” characters aren’t that naughty, because if they were we wouldn’t care about them. Like, the Arrested Development folks can be self-centered, but they do seem to care about each other in the end. And my You’re the Worst characters seem pretty horrible from the outside, but they treat each other with respect and affection. If they were really just abusing each other nobody would watch.

John Perich: I like this rubric. I suspect it’s not even possible to have a “Naughty” show prior to Seinfeld, though. Larry David’s style was so groundbreakingly cynical.

Belinkie: Well, All In the Family arguably, although it’s interesting to think about whether Archie is supposed to be rejecting the status quo or embodying it.

But even going back to Commedia dell’arte, there are characters that represent the forces of law and order (usually the rich and dumb), and characters that try to undermine the system (usually the poor and cunning).

John: I think All in the Family is much “nicer” (read: more optimistic about the triumph of the nuclear family over life’s adversities) than Seinfeld. Archie Bunker is a bigot, of course, but that bigotry is always presented as the butt of a joke.

(This leads to an interesting tangent on whether the show’s writers were having it both ways – appealing to genteel liberals by making the racist a buffoon; appealing to beer-swilling conservatives by having a guy who Tells It Like It Is. I’ve seen similar critiques aimed at South Park, Archer, and other “edgy” shows. But I digress!)

And the primary audience for Commedia was the vulgar populace anyway. So the skewering of the pretensions of the rich and the triumph of the likable servants was purely a good thing.

But Seinfeld ended a season with George’s fiancee dying because she licked cheap envelopes for their wedding invitations. And that was the punchline. It was played for laughs. And it was funny!

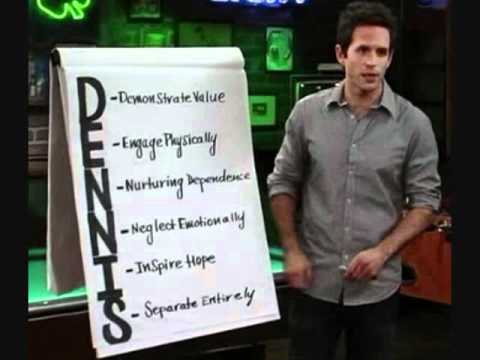

Most early episodes of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia end with the gang’s terrible schemes succeeding, or the gang’s terrible schemes failing. But, in the few that a genuinely good person receives the reward the gang was scheming for, there’s always a twist or a complication or some final punchline to keep us from enjoying dramatic justice being satisfied.

Stokes: I mean, if you go back… The Clouds ends with the thinly-veiled Socrates character getting burned to death. That’s the punchline. The Country Wife ends with Lord Horner schtupping the titular Wife six ways from Sunday, much to her husband’s dismay. And that’s the punchline.

Matt Wrather: “Horner? I just met ‘er!”

Stokes: Well schmaaaaactually, Matt, as I’m sure you know, the people getting “horned” in that play are the husbands, as in “made to wear the cuckolds horns.” So that ought to be “Hornim? I just met him!”

Which just goes to show that Wycherly was every bit as goofy and juvenile as you are, if not more so. I mean, he wrote that joke into the character’s name.

I dunno, part of me thinks that the naughty/nice scale is a good metric, but another part of me wants to say that comedies are always about propping up the social order: it’s just that the social order isn’t quite what you think it is.

Like in Happy Gilmore… Is Shooter McGavin “the social order”? I mean, really? He’s high-status within the world of the film, but everyone watching it is like, “I can’t wait for that guy to get hurt.” If everyone’s thinking that, then where does he actually fit into society?

Bakhtin wrote that comedy is about breaking down the old, false social order so as to make way for the new, true social order.

Maybe all comedy is both naughty and nice, depending on where you happen to stand?

John: That’s fair. I guess maybe my insistence on how deeply today’s “naughtiest” comedies want to fracture the old social order.

For instance, The Miller’s Tale attacks the balance of power that lets bourgeoisie men marry hot young women by having the carpenter get cuckolded by two scheming clerks.

Seinfeld attacks the balance of power that … lets people be fundamentally courteous to each other.

(It’s Always Sunny maps pretty well to ancient tales of knaves getting their comeuppance, so I won’t press the case there)

Peter Fenzel: Shows like Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia do tend to pretty severely indict the pop cultural understanding of the current social order.

But the pop cultural understanding of the social order that feels right and comfortable, I suspect, is pretty distorted.

Like, is Dennis supposed to be a normal person?

I think he is.

An exaggeration, of course, but an honest one. Certainly all our recent talk about the movie Passengers seem to indicate that “the implication” of trying to seduce a woman on a boat at sea is drawn from some sort of shared cultural space.

But as John said, Sunny does map onto old ideas of comedy comfortably, probably at least in part because the “gang” is lower class than it thinks it is.

But to step back a second, I think a big part of the joke in The Miller’s Tale is that the Miller is old, and he expects his money and station to dictate the sexual life of his wife, and that doesn’t pan out, because the young want to have sex with the young. Same with The Country Wife – there’s an expectation being lampooned that the common virtue of social station and the temperance of pseudo-pastoral life will rule over sexual urges, and of course they don’t – Restoration comedy is in this way lampooning the foolishness of roundheaded Puritans.

So the humor about the commonly understood rules and practices of screwing around and the humor about money, status and social standing might be extricable, or at least in parallel. It’s not that it’s concerned strictly with an elevated subject.

And I think similarly the venal sort of disruptions we think of as characteristic of modern shows might also be coupled with more “serious” concerns about the world if we were to drill into them a bit.

Like how Sheldon in The Big Bang Theory is pretty cruel to everyone, and he’s also technically savvy, smart and entrepreneurial, so it’s comedy about commonly held disrespect for the bosses of the knowledge economy.

But it’s also harmless, observational comedy about Star Trek and stuff.

I like the division between “naughty” and “nice,” but I’d suggest that both of them “arc.” Nice comedy arcs into naughty territory before coming back to nice. Naughty territory arcs into nice territory before arcing back to naughty. And by naughty and nice here I mean Belinkie’s definition – whether you are in accordance with or in opposition to “The Rules.”

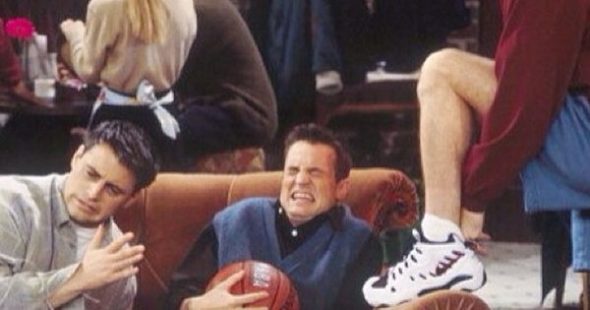

I think people remember Friends as a bit more harmless than it was – it was by the guy who came up with Dream On, remember.

So, take the Friends gag where the Phoebe is dating the dude who wears short shorts (from “The One Where Monica and Richard are Just Friends”). He shows up at the coffee shop wearing short shorts, and everybody can see his testicles. There’s a pretty intense critique that happens – Chandler accuses him of “bursting into flame” and says he is “coming out,” and there’s this whole dance about sequestering the members of the group because they can’t directly talk about the visual presence of his testicle. Chandler and Ross agree that they can’t “look directly at it. Like an eclipse.” Disapproval for being able to see something they all know the guy has is equated to a natural phenomenon that would hurt them physically.

From our standpoint, this is just a balls joke – quite harmless; balls are funny looking and make people uncomfortable. But there are more far-reaching social implications of what is happening – “you have to dress like the people around here, or we will all shame you” feels like a pretty old-fashioned comedy lesson.

But this is also up against the backdrop of Courtney Cox and Tom Selleck resuming a relationship as exes, which is a similarly forbidden sort of thing as showing your balls in public – the hard and fast rules against them, weak as they are, are not the main driving energy behind their enforcement – more the soft social condemnation, coupled with some evidence that it might be a bad idea for practical reasons. The Tom Selleck sexiness and the nice chemistry the two of them have together do call into question this social norm – which is more important to the lives of most people, directly, I think, than a lot of topics that seem graver because they are more academic in nature. Sexual politics are a big deal.

At any rate, over the course of the episode, the main conflicts are about breaking the rules, but the show arcs back toward restoring the rules. So it’s a “nice” show, but it’s primarily concerned with the emergence of “naughtiness.”

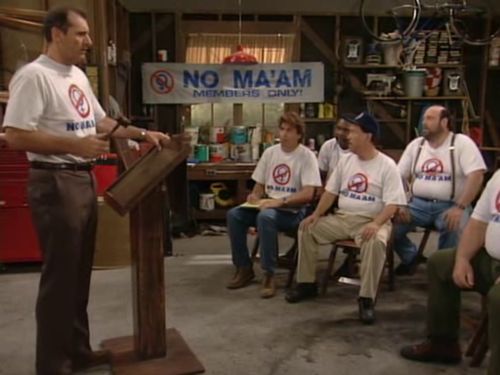

I might compare this to a Married: With Children episode, like one of the ones with “No Ma’am” in it, Al Bundy’s “MRA before it was cool oh it was never cool” group – where it starts out that Al wants to break the rules, and in the middle, he becomes the rules, and it looks like the world is going to go his way, but then at the end his plans fail and he goes back to normal.

Frasier as a “nice” show has tons of critiques of Frasier and his life and has him try to break all sorts of social rules because of his vanity, idiocy, arrogance and bluster, but then at the end things go back to normal, and the thing that makes it feel nice is that Frasier is fundamentally on the right side of normal (my guess is a big part of this is he helps people for a living and likes doing it).

South Park as a “naughty” show has a ton of moralizing and telling you how the world ought to be, but it’s in the standpoint of setting up a straw man order and then destroying it.

Personally, I’ve always tended to favor what I’d term “functional” definitions of comedy – that the humor is in the leaving and coming back, and the social order is just one vehicle for it – though if you see the world in terms of frameworks of social order, then everything is the social order, so of course all the cycles and arcs of comedy can be seen through that lens as well.

But I don’t disagree with any of the different naming schema here, it’s more a matter of preference and what you’re trying to accomplish when you’re making it. What sort of truth you’re going after and why – and then the viewer/reader can critique from their framework, and if it’s good it will probably translate.

Maybe the deal with Seinfeld is that they live a life of general comfort and luxury despite being, for the most part, utter failures, and that larger critique of how or why people are rewarded in the world of the 90s hangs over all the greater and lesser things that they do.

Because I know in the critiques Seinfeld is seen as about amoral, terrible people, but I never felt that way watching it at the time – to me it felt more like a “nice” show. They were friends, they cared about each other, they had a nice life together. Which is also perhaps why for me the the series finale fell so flat and felt so wrong as a conclusion.

I don’t disagree with the evaluation now, especially in light of the crystallizations Larry David’s subsequent body of work, but yeah, if we’re looking at the perfect example of a “naughty” show, I would expect Seinfeld to not prove out.

It’s probably the case that both kinds of shows have “naughty” or “nice” episodes in different measure, though the premise and characters would lend themselves better to one or the other.

Add a Comment