Jordan Stokes: Have you guys seen this truly excellent trailer for a Mortal Kombat adaptation from Ghana?

There’s probably an interesting overthinkable angle here, about how the fight choreography here is totally awesome and yet ridiculously fake looking. Like, we tend to sort of think that fight scenes are good when they look real. (Which leads eventually to the GPBSF, or Generic Post-Bourne Shakeycam Fight.) But this flies in the face of ALL the available evidence, such as:

- Pro Wrestling

- MMA

- The Career of Bruce Lee

- The Career of Jackie Chan

- Olympic Fencing

- The Career of Errol Flynn

- That One Sword Fight From The Princess Bride

- The Matrix

and so on. Fight scenes that look real and are great do exist, but they’re more the exception than the rule… verisimilitude and goodness are kind of orthogonal here. That being the case, what does make it good?”

John Perich: So I’d like to quibble with one of your assertions, Jordan, and in doing so hopefully shed light on the discussion.

In the modern Panopticon, thanks to YouTube and Dailymotion and WorldStarHipHop and a dozen other sites, we have a pretty good idea of what a “real” fight looks like. It’s usually two dudes circling each other for an uncomfortably long time, neither willing to commit to a fight or admit to reticence. Or it’s one dude charging in, flailing awkwardly, while the other shoulders him away.

Bourne Shakeycam looks more “real” to us because it’s fast and close-quarters. But the interplay of blow and parry is just as staged as the most elaborate wushu display (from which the fight choreography of Jackie Chan and Jet Li emerges).

“Realistically,” two people fighting at the close range that Jason Bourne fights his assailants will be struck a dozen times over. But in a movie fight scene, every hit has to be significant. The hero has to reel a little, the audience has to doubt the hero’s ability to triumph, the music has to swell.

Long story short, I think “posed” vs. “frenetic” is a more useful scale to evaluate a movie fight scene on than “unrealistic” vs “realistic.” There are fight scenes that showcase their choreography – everyone needs to see Jax pummeling his opponent – and there are fight scenes that obscure it. But there’s always choreography.

Matt Belinkie: I watch a lot of martial arts movies. Those tend to be at the extreme end of some kind of spectrum, in that they’re extremely unrealistic and all about the performers showing off for the audience, both in terms of physical skill and in terms of creativity. The Jet Li clip reminded me of one of his classic works, Fong Sai-Yuk. In the movie’s most delightful scene, a mother says that any man who can beat her in a fight can marry her beautiful, rich daughter. The fight takes place on some kind of wooden structure, and the rules are that the first person to touch the ground loses. This leads to all kind of fun moments where the fighters ALMOST touch the ground but manage to save themselves, culminating in a sequence where the fight moves onto the heads of the onlookers.

This is obviously ridiculous, but it’s actually a variation on a martial arts cliche where the fighters stand on bamboo poles high over the ground (see the final fight in one of Donnie Yen’s early works, Iron Monkey). This kind of thing just wouldn’t happen in real life, but it’s super fun to watch.

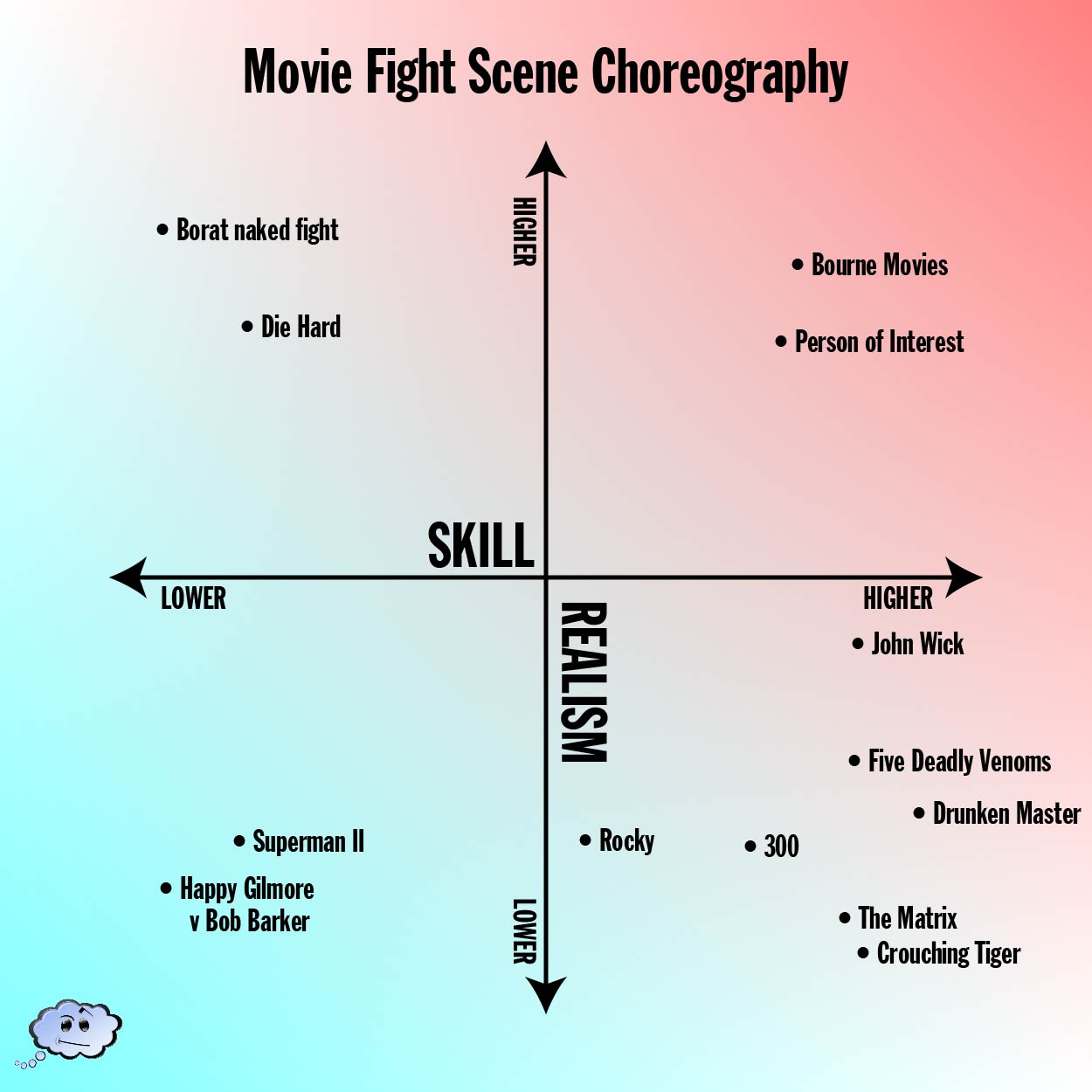

Maybe the scale we’re looking for has two axes. One axis is the level of skill of the participants. The other axis is the level of “realism.” I use realism in quotes because I don’t think we can judge how realistic something really is, but we can judge how realistic it presents itself as. So for instance, something like Die Hard, the fighters aren’t supposed to be that skilled (John McClane is a tough guy but he doesn’t have any special moves), but the action is gritty and “realistic.” Fong Sai-Yuk or The Matrix has skilled fighters doing unrealistic things. The Bourne movies have skilled fighters doing “realistic” things.

Stokes: Those are useful quadrants! So, when I say “real,” I don’t mean “actually real.” I mean verisimilar. Do we think it’s real? Or assuming we’re not such idiots as to think that Matt Damon is actually beating these people do death, do we think it feels real?

I think of this in particularly in relation to professional wrestling, where we know that it’s all fake, but still talk about the ability to “sell” or “put over” the strikes and the slams. (And my inspiration here is OTI muse emeritus Roland Barthes’s “The World of Wrestling,” which is a must-read.)

What’s interesting is that you have wrestlers who fit into all four segments of your graph, and their ability to put it over is distinct from ALL of these!

You have your sproingy Lucha Libre types (think Jet Li), your Stone Cold Steve Austins (think McClane), your jobbers (unskilled fighters doing realistic things), and, like, The Undertaker (think superheroes). But all of these can be put over… or not.

I would say that these archetypes have different relationships to “realness,” though. When you have skilled fighters doing unrealistic things, “realism” is less necessary. If you’re a Rey Mysterio type and you can’t make the other guy’s punches look good, so what? You still nailed that double backflip powersplash off the turnbuckle. That looked Cool.

Jobbers, though, are guys whose role is to lose convincingly. Like, I can imagine a wrestler whose shtick is responding to every blow with a cartoonish, Three Stooges-level pantomime of agony. But as far as I know this isn’t actually a thing.

(Reading over what I wrote, I think I got confused about what your chart was supposed to track halfway through. That’s the problem with these think tanks: we write them on the fly. Still, I think we’re on fertile ground here. You see how what I’m talking about relates to what you were saying, right?)

Belinkie: I think I was underselling the complexity of “realism” in a fight scene. Even in the most stylized kung fu movie, the performers need to sell that they are responding to each other’s moves (not just executing the blocking) and that the strikes actually hurt. When you watch something like The Raid, you wince, even though (for the most part, hopefully) the blows aren’t connecting.

Stokes: John, I think “posed” vs. “frenetic” is a very good way to think of this – but I’d add that, perhaps because of the very access to violence that you discuss, posed feels much less real than frenetic does. (Like, yes, real fights don’t move as fast as Bourne’s do, but they move SO MUCH FASTER than Rocky does.)

John: I think the degree to which we want realism in a fight (or rather, the degree to which we eschew posed-ness) has a lot to do with genre. In superhero movies, for instance, we want heroic poses. We don’t particularly want Iron Man’s ribs to be broken when Thor backhands him out a window.

In wrestling, we want the luchas to really sell their acrobatics, and we don’t want The Undertaker to do much more than sit up ominously or chokeslam people. If wrestling had the awkward clinching and close striking of MMA, fans would hate it.

So to your original question of what makes a fight scene good, I would submit: when its position on the “posed” vs “frenetic” spectrum matches with the tone of its subject.

Stokes: Yes. Yes! And in the specific case of Mortal Kombat, anything other than maximum posedness would be a grotesque error of judgement, right?

“For what would be more out of character, than to use a lofty style, and ransack every topic of argument, when we are speaking only of a petty trespass in some inferior court? Or, on the other hand, to descend to any puerile subtilties, and speak with the indifference and simplicity of a frivolous narrative, when we are lashing treason and rebellion?”

– Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Oratore

Perhaps a third access could be “how much of the fight do we actually see?” The first thing I think of when Jason Bourne action sequences are mentioned (along with the many movies made in a similar style since) is how difficult it can be to track what’s going on on-screen. This is a handy filming tour when you want to make a fight look brutal without actually brutalizing your actors, since the audience will mentally fill in whatever gory details they don’t actually see.

Not-showing action moments can be done very effectively (stabbing scene in the original Psycho) or ineffectively (the multitude of incomprehensible action sequences in recent movies.) Of course, I’m not sure how to quantify that – I’m not a big enough action fan to call to mind a sample size for comparison’s sake.

Since Olympic fencing, Errol Flynn and that one sword fight from the Princess Bride are mentioned, I feel as though I should recommend one of my all time favorite unrealistic sword fight movies: Scaramouche. Here’s the trailer (I can’t find the whole, minutes-long sword fight at the end on youtube). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yzYEYyOsQtA