1.

You come into possession of a long lost manuscript by your author, stashed away in a safe deposit box for the past fifty-five years. At first you weren’t sure what it was, but when you give it a close look it turns out to be the novel that she wrote before the novel that made her famous, the one that was so brilliant and incisive that it transformed people’s ideas about prejudice and injustice in their country, a novel so important and true that it became mandatory reading for school children.

This is the one she wrote before that. It was not accepted for publication at the time, and you understand why: it’s a fairly aimless, sometimes confused piece of writing. It is not bad, but it is the work of a very amateur sort of genius. All of that notwithstanding, it would be a guaranteed bestseller if published today, both because of the author’s current fame and for the controversy that is guaranteed to erupt over its content. The hero of the published book is revealed to be less than perfectly heroic in some very troubling ways. This heartbreaking complication of his character is the point of the book, but the revelation is certain to play just as poorly with this character’s fans as it does with his daughter, whose crisis is the novel’s central issue. The book may retroactively taint readers’ feelings about the book they originally loved.

You ask the author her opinion. She is close to 90 years old now, but you have no reason to believe that she is not of sound mind. She says it’s fine.

Do you publish it?

2.

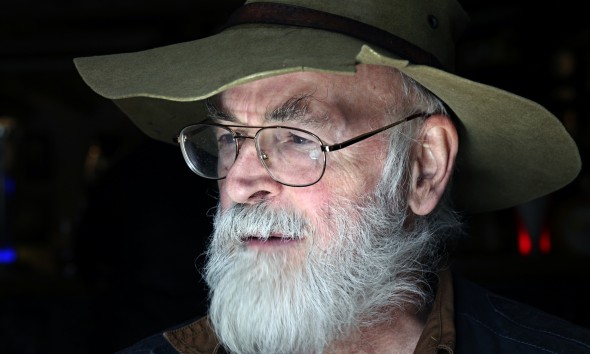

Your author is one of the most popular and celebrated in his genre, with a career spanning more than forty years and dozens of publications. Tragically, he is diagnosed with a rare degenerative brain disease and probably has not long to live. As a result of his condition he can no longer write or type, but must dictate to an assistant or to voice-recognition software. He delivers to you what will, in all likelihood, be his final novel. It’s pretty bad.

It seems clear to you that the illness has harmed something about his ability to write – the characters are the same but their voices are wrong; the formerly colourful and wild world he had created over the decades seems charmless and dull. The book just doesn’t sound like him anymore. This is not, of course, his fault. But the fact of the matter is that it is a disappointing, sub-standard novel that you would not ordinarily accept for publication.

But it’s him. The book will be a bestseller because a good proportion of his audience is so devoted they will buy anything that he produces. Many of them will probably even like it. You don’t want to demand a major rewrite, because the author may have neither the capacity nor, sadly, the time left to complete them. It is a book by a once-brilliant author who is rapidly forgetting how to write.

Do you publish it?

3.

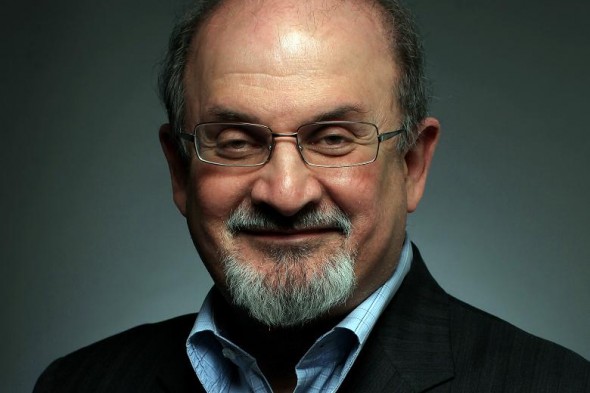

Your author, already internationally celebrated and the winner of one major award for a previous novel, turns in his new manuscript. It makes you nervous. It’s certainly brilliant, a work of magical realism in the tradition of his previous books and a powerful metaphor for the immigrant experience. But it also contains some material that is…let’s say…provocative. There are passages that make certain negative intimations about the revered prophet of a major world religion. The religion that your author was raised in, but also a religion with a number of adherents who have a reputation for dealing very poorly with depictions such as this one.

It’s arguably his best work to date, but it’s also a very dangerous book. Literally dangerous, in that it could – in fact, will almost certainly – get people killed. Not only the author himself, but anyone else even tangentially associated with the book will be at risk. Publishers, foreign language translators, booksellers – and you. If you put this book out into the world, you will be risking people’s lives. There are those out ther e in the world who would murder other people over a novel, and this is that novel. Not to belabour the point, but to emphasize the implications of this act of artistic expression: if you publish this book, innocent people will probably die.

Do you publish it?

4.

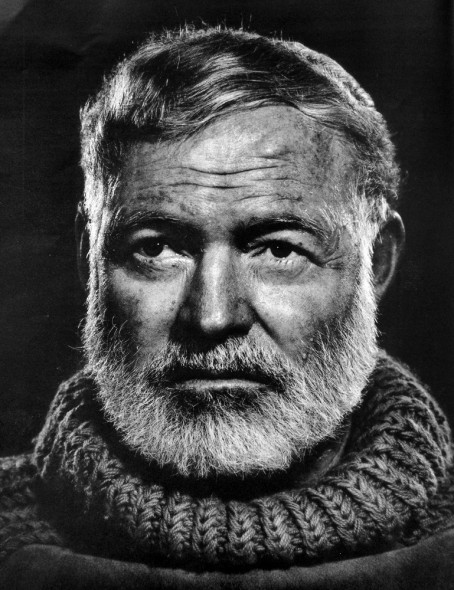

Your author is dead. He recently committed suicide after a decades-long career. He won the highest awards and changed the face of writing, and then (in what seems to have been a family tradition) he committed suicide.

His wife, as executor of his estate, retrieved a number of the authors notes and documents, originally written decades before and more recently rewritten by the author into a sort of memoir. The manuscript details the author’s experiences while he was a member of a celebrated literary circle at a crucial moment in English Literature. The author’s personal reflections on that period, and his interactions with other major writers, his friends and rivals (often the same people), would be of infinite interest to fans of the author and his contemporaries. It would be an instant bestseller.

Here are the problems. The manuscript was presented to you by his wife – his fourth and final wife, that is – and she seems to have done some work on it. You can’t be sure exactly, but you have reason to suspect that she may have altered or removed certain passages; for instance, some of the stuff the author wrote about his first wife, to whom he was married at the time of the described events, that cast his last wife in a comparitively negative light.

The other thing is that the memoir describes several events and encounters with the author’s famous contemporaries that are unflattering at best, and potentially libelous. For instance, one literary giant is alleged to have badly abused her partner, while another is portrayed as a pathologically insecure coward who requires assurance that his penis is a normal size. This book is a powerful illumination of a literary zeitgeist, but is also likely to make some people very upset.

Do you publish it?

5.

Your author is your best friend, and also quite possibly the greatest literary genius of the century. He’s always been extremely self-critical, and out of every ten manuscripts he produced he’d usually destroy nine of them. Despite this, he’s built up a pretty serious collection of writings, and pretty much all of it is exceptionally brilliant.

Only a handful of his short stories have been published – a small proportion of his life’s writing work. And now he tells you he’s dying. He’s dying, and he tells you that after he’s dead he wants you to take all of his writing – stories, novels, journals, letters, everything – and burn it. Don’t read, just burn. He never wanted fame or recognition, and since these are things particularly useless to a dead man, he wants you to destroy it all.

And so he dies. And you’ve got all this stuff. You can either respect his request and burn everything, or you can disobey his dying wishes and get it all published instead – invoking his wrath from beyond the grave, maybe, but also enriching the culture of the world for centuries to come.

Do you publish it?

1. Yes. Put a lengthy foreword in the book explaining the circumstances (“It’s a prequel!”), and make sure that gets mentioned in all the press.

2. Yes. For historical importance, if anything. Heck, even Shakespeare wrote some rubbish.

3. Pass the buck to the Legal Dept. Do what they say.

4. Yes. Let the chips fall where they may – and let literary historians and critics sort it out.

5. Share it all with his and your close friends. Then, after some time has passed, publish the stories and archive the journals and letters.

Seems to me the answer is always “yes”. But there is a “dog that didn’t bark” problem is that we do not know of posthumous works which haven’t been published. For example, what wouldn’t scholars do to get at all of Jane Austen’s works which were burned?

I haven’t heard of the Hemingway one, which book is that?

I feel like for all of them, too, there’s a historical horizon issue… I am really glad that Max Brod didn’t burn all of Kafka’s papers. That seems unambiguously good to me, at this point in time. If the Harper Lee thing had played out like that, I probably would feel conflicted about it though.

And even with Rushdie! I think the answer is *probably* to go ahead and publish in any case, but if I had to make that call tomorrow I’d lose sleep over it. And my reasons for publishing it would not be “I want people to be able to read the book,” it would be “we can’t set the precedent of allowing terrorists to preemptively censor anything they find offensive.” But if I imagine looking back on the event from 200 years in the future, long after everyone who might have died would be dead in any case, suddenly the fact that the book is brilliant starts to carry a lot more weight.

Was it known before publishing that The Satanic Verses would be controversial? Or was that a surprise to the author and publisher?

To my cynical mind, the real question is “will this make money?” and, more importantly for the books that may tarnish the image, “will this make more money than not publishing it and relying on current books?” If the answer is ‘Yes’, then publish.

And there’s another situation that could have been proposed. An author is working on his next book, but dies tragically. You have his first rough chapters, and they are very rough, and not up to his usual standard, but you know the world will buy it anyway, although they may condemn you for trading in on the author’s rough work. Do you publish?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Douglas_Adams

In that case, ask around among his writer friends and colleagues if any of them would like to finish it. Publish it as a collaboration.

For me, the question is largely about whether we’re mature enough to consider the work for what it is when it’s something that was never meant to be published. Are we able to think about it critically and add it to our understanding of an author without blowing everything out of proportion and remembering that the author didn’t feel confident enough in the project (because it was unfinished or because they just didn’t want to release it) to have it published? That said, I don’t think everything DESERVES to be published.

#4 is more complicated because it isn’t fiction.

First of all, it’s hard to take those examples at thought experiments, since, well, they aren’t. We know what books and authors this is about, so this is only a hypothetical discussion in so far as we here don’t actually decide to publish or not.

But here would be my thoughts:

1) Definite Yes. If there exists some sort of supplementary marterial (be it a draft, sequel or prequel) to such a well-known and influential work, making it publically available is important, for scholarship value alone. I think it’s far-fetched to say that the positive social impact of the original would suffer by publishing the draft to it. I am aware of the controversy that it might have been published against Lee’s will (which I do take serious in regard to living people), but it’s just not clear-cut enough, and I would err on the side of publication in such a case.

2) Definite Yes. No reason to declare myself the gatekeeper on this one. Pratchett wanted it published, a lot of people want to read it, and, again, I don’t see how the already-published works would suffer.

3) Yes. It’s tempting to say that human lives are more important, but the very reaction to the Satanic Verses proved that it’s publication was necessary. And I am not just talking about the murders and death threats, but also of the supposedly “more civilized” responses by “western” politicians and journalists, who also wanted it banned. And it was important to shine a light on those. Religiously motivated murderers exist, but if they murder authors and book-sellers, they get noticed. The book didn’t cause killings, it just directed them. And people who want to ban things in the name of “offending religion” have to be opposed at every turn. A religion is an ideology, and a choice (one you might have to keep secret, but that can apply to every ideology).

4) Eh. Depends if I can frame it to my liking. I have no objection if it can be published with the preface that this might have been posthumously edited. Literary significance and all that, see 1). But if I am unable to do that, I would pass that one over.

5) Cautionary Yes. I have to admit, I probably wouldn’t. I would definitely keep it, but probably only make it public at my own death, to let others deal with it. It’s not because of Kafka, because Kafka’s dead, and I think it’s very dangerous to let the opinions of dead people influence decisions (it’s the reason I stressed that Lee is still living up there). But I would have to consider that maybe Kafka didn’t intend for the publication for other reasons, reasons that might damage people still living. So, at best, I would very carefully go through all of it, and then maybe publish selected works I felt would be both interesting to the public and academia.

Tricky. My take is that to look at the work itself. Ignore the circumstances. Does it deserve to be published? Is it in any condition to be published? Would you reject it if you didn’t know the circumstances behind it?

If the answer justifies the decision not to do it then don’t do it. Publishing crap just to make money doesn’t serve us well. This doesn’t mean unreleased, in our grand new world, not being published is not the end of times anymore. But cynical cashgrabs aggravate.