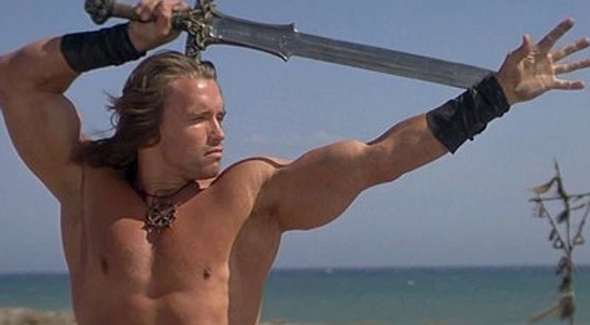

We have already addressed on Overthinking It that the sitting president of the United States is a big fan of Conan the Barbarian. So, on the day of election for that office, let’s consider the great political lesson of that fine film, “The Riddle of Steel”:

Steel isn’t strong, boy. Flesh is stronger…That is strength, boy. That is power: the strength and power of flesh. What is steel compared to the hand that wields it? Look at the strength of your body, the desire in your heart.

There is a conventional wisdom in the United States that Election Day precedes power. That a politician running for office is at his weakest, and that once he or she wins, there is a mandate, and the politician has the power to do things that matter.

Thinking of it in terms of the Riddle of Steel, though, and there is no day a politician is more powerful than on Election Day. On Election Day, the politician summons flesh across the continent to exert its energies on his or her behalf. More people are mobilized by the incipient President of United States on a given Election Day than were mobilized during the D-Day invasions of Normandy.

And, perhaps even more shockingly, more people are mobilized by the candidate who does not win on election day than were mobilized at the Battle of the Bulge, by many times over. So the losing candidate, despite seeming weak or ineffectual by conventional wisdom — a power that never had a chance to happen — is, by the wisdom of the Riddle of Steel, a tremendously powerful individual.

Conan the decider

Of course, it is not that simple. Perhaps we are more interested in policy outcomes than in winning elections (which would of course put us at the far end of an uncrossable gulf from any credible politician) — in that sense, elections feel trivial — a theater, a waste of time that should be spent working.

Except of course, who accomplishes policy goals? We are reminded constantly of “how the sausage is made” — of the negotiation, compromise and entrenched interests that end up conducting most of the governing that actually happens. We so rarely see the outcomes we actually want from the political process, but this is not because of the intentions of any one individual being at odds with our own, it is because

- “We” are not a single unified perspective and actually people disagree a lot on what they want to see happen

- A lot of what happens during governing is the product of institutions, long-term commitments, entrenched incentives and operational limits, rather than decisions by individuals

We all saw this in action during on the defining political moments of recent years, the 2011 debt ceiling crisis. The debt ceiling debate is always theater, because it is never possible to change the federal government’s financial commitments or revenue streams quickly enough to stay under the debt ceiling once the issue is urgent enough to grab the public interest. Historically, the party of the president supports raising the debt ceiling, and the party against the president opposes it, and they play silly games until they eventually raise the debt ceiling (and of course last year they screwed up the games and hurt the country for no reason, but that’s another conversation).

This is not because “Washington is broken” — maybe Washington is broken, but this is not why, once the debt ceiling has made headlines, it always ends up getting raised. The proportion of spending by the federal government that can be changed on short notice is actually very small, relative to the size of the overall budget. We live with the myth that everything the government does it up for complete revision in the short term at any time, when in truth:

- As we are perhaps soon to see with the 2013 fiscal cliff, even relatively minor shifts can have profound economic consequences and are usually not feasible.

- In most cases, the commitments are already made, and even the president can’t back out of all obligations (the judicial branch provides a balance against that power across government, by, for example upholding lawsuits over things like municipal bonds)

Read some Congressional Budget Office writing on discretionary spending. Sixty percent of the budget in any given year is already committed and can’t be changed, even by the actual budget process. Half of the remaining 40 percent is for defense, which has a very complex budgetary process and volatile expenditures can’t be changed quickly (it’s not like you can return the stuff and get a refund, making small changes takes years). So you’re left with about 1/5 of the budget that you can even consider changing during a crisis.

Growth and contraction of discretionary spending as a share of GDP happens in single-digit percentage point swings over decades. For all people’s talk of being able to revolutionize taxing and spending and all that, there really isn’t all that much that anybody can do over a short to medium time frame — even a four-year presidential term.

Now, I don’t want to get too far into the weeds here — it’s very possible you disagree with these specifics and it’s very possible you are right. But regardless of how you see it, these sorts of institutional functions are the steel; they aren’t the flesh. The appearance of power in the high-level budgetary process is nothing next to somebody who actually has the power to do, well, pretty much anything.

Institutional policy choices are not powerful. They loom. They threaten ominously. But they do not strike a blow or command anybody to be eaten by a snake.

We all like to reassure ourselves (or else we should like to reassure ourselves) that the president doesn’t really have all that much power over the economy. Certainly on a day-to-day basis, this is true — if we see the president as an executive running an organization with policy outcomes, the president isn’t very powerful at all, because all the institutions at his (and someday her) beck and call are themselves already doing whatever it is they are going to do in the near future, regardless of what he says.

Who’s the boss?

Let’s briefly consider the president as an executive. The business world is full of “power rankings” (here’s one from Human Resources Executive Online) and I have a huge problem with them — because they almost never measure actual power. They measure a person’s prestige, sure. A person’s salary and bonus, sure. Above all they measure the scope of resources nominally under this person’s supervision and the outcomes produced by those institutions when that person happens to be at the helm.

But implicit in all these rankings is the understanding shared by executives and conveniently glossed over in the praise offered them — that only in the most indirect or the most absurd fashion can any of these executives ever be said to have done any of these things themselves — and that being put in charge of the right team is going to be more important than almost anything else in how people perceive your power.

But, when we praise powerful executives, are we praising flesh, or are we praising steel?

It is not just possible, but common, for an executive to be named to a prestigious list of most powerful executive in the same year that the executive is fired — and people are about as likely to comment on this as they are to go back and review the January economic forecasts for the coming year (spoiler: they are no improvement over random chance). This, to me, seems to reveal a gap in the understanding of power — because how can a person be said to be powerful in business if he or she can’t even hold onto his or her own job?

This takes us back to the presidency and to Election Day. At the end of the day, the president’s actual job is as an executive, and executives have a lot less power than their mythology would like to admit. We call the President “The Most Powerful Man in the Free World” and other such epithets — but how powerful can you really be if you wake up every day in fear for your job, or if you spend a year out of every four groveling before strangers, eating pancakes for the amusement of others like some sort of carnival animal?

The answer of course is a profound irony — the times when politicians seem weakest — elections — are the times when they touch the most people, have the greatest influence, and can do the most to shape the years ahead — both the winners and the losers.

The finger with the power to control the universe

There is yet another, more powerful irony to the Riddle of Steel. In the famous speech from Thulsa Doom in Conan the Barbarian, we see his side of the story — but it is easy to forget Conan’s. Conan overthrows Thulsa using the same power that Thulsa uses to enslave his followers — the power of the flesh, the will to do things himself, and his ability to inspire the followership of others. In the executive power rankings, Conan would be far, far, far down the list below Thulsa, but in power as understood by the Riddle of Steel, he’s right up there at the top.

This reminds me of the newly-Disney film Willow, which has another great riddle about the nature of power. The town wizard shows up every year looking for an apprentice, holding up his hand, and asking the hopefuls to choose the finger that controls the universe. He explains the riddle to Willow later:

When I held up my fingers what was your first impulse?

“Well, it was stupid.”

“Just tell me.”

“To pick my own finger.”

“Aha! That was the correct answer.

Election Day is also a very powerful day for individuals, because we get to set our vote for how we want the steel of government to take shape, and, more importantly, we can exert our will over others, through get out the vote canvassing and mobilization, nagging friends and relatives, participating in phone banks, and all sorts of other activities.

The “incipient president” and “the guy who loses” are both tremendously powerful, but it is debatable how much it is their own flesh commanding, through extension, other flesh, and how much the power instead belongs to the many people who choose to apply their own flesh to the day.

So, like Conan against Thulsa, we should not mistake the person with the power for the person with the army or the giant snake. Part of the Riddle of Steel is that its power passes from person to person rapidly — I mentioned before that during budget negotiations the institutional bore drills on without a driver, but it’s more precise to say that that the history of true power is a microhistory — of innumerable small acts of will, rather than a few big ones.

This is especially true in a republic like ours, where such temporary things as fortune, scandal, allegiance or even the weather hand power from person to person frequently — a few very large pieces of steel, but many many more powerful pieces of flesh.

And of course, republics like ours designate sacred days of great power, when everyone from the president down can marshall the true power of the flesh — when every political agent calls forth across the country for various maidens to jump into various snake pits, except the snakes are voting booths, the maidens are wearing more clothes, and you get a sticker afterwards.

Fenzelisms

Well technically Obama’s only stated to be a fan of the 1970s comic: his opinion on the film is, as far as I know, unknown. But let’s not get bogged down in details.

Nice “well actually!” Thanks!

Just FYI, the word “flesh” appears 11 times on this page.

Your point about the power rankings is very true. In the public imagination, the President (any president) has absolute power over the deficit, gas prices, foreign affairs of other countries, the stock market, etc. He will get credit when things go well, even though he had absolutely no impact on them, and he will be blamed for bad news that he had no control over.

I think deep in our simple, caveman brains, we need to think of one guy as the Leader. The idea that Congress passes laws, the President executes them, and the Supreme Court resolves disputes just doesn’t capture our imagination. The law is OBAMACARE, despite the fact that Obama didn’t write it or pass it.

I notice that the ‘power of flesh’ Conan spoke about has certain similarities to the Ubermensch,what with one of the most important tropes of Conan being his similarity to a one man army, where as your power of flesh when talking about the American political system seems to talk about people who have the power to summon a mob to give pre-eminence over another mob over which they have no real power. Am I missing something? Is the point that they and Conan mattered less when they came to power, a conqueror but not a king? Its been ages since I read/watched any Conan stories so I might be completely off mark with all this.

Sorry, I mean the articles power of flesh not *yours.

Hey Sunsphere,

The Riddle of Steel is a bit different from the Ubermensch — I’ll try to explain why (apologies if my Nietszche is rusty or imprecise). There are two basic reasons:

– The first is that the Ubermensch, while not necessarily “ideological,” is “idealized.” He’s not a real person — like a messiah who comes along and breaks all bonds. He’s more an aspirational form, like a “perfect circle.”

Whereas the “flesh” in the Riddle of Steel, while it is in this case fictional, has a correspondent relationship with reality. This is something people can actually do fully in real life, to a greater or lesser degree. There’s no “perfection” to it.

– The second is that the Ubermensch is a moral being, not a practical being. In being freed of all responsibility to moral authority, the Ubermensch is not free of all hindrance, but free of all justifiable reasons why he can’t do the things he wills to do. When the Ubermensch wills something, it is always okay, because no justifiable objection can rise as to why it is wrong.

Whereas the Riddle of Steel doesn’t really address what a person ought or ought not to do, just what they can or cannot do. This may seem similar to the Ubermensch in a sentimental sense, but it’s a different dichotomy. When we say the flesh in the riddle of steel can’t be prevented from what it is trying to do, what we mean is that personal energy, strength, heart and the capability to exercise power in the world are difficult to oppose by pragmatic means — that it is difficult for an army to stop one man if that man understands the power of “flesh” over “steel” — the power of heart and strength over essentially disinterested institutions, tools and resources.

Conan the Barbarian may discard or refute a certain degree of bourgeoise morality by appealing to the role of strength in ruling the world, but it doesn’t eliminate it entirely.

Thulsa Doom gets to do what he does because he is strong, and Conan is similar to Thulsa Doom and opposes him because he is also strong, but they’re not the same.

Even in the wild Hyborean Age, Conan is still good and Thulsa is still bad. Just because Thulsa has the strength to not be stopped, that doesn’t mean his various snake-related atrocities are ethically or philosophically justifiable. Conan, meanwhile, is generous, loyal, caring, principled, dutiful, brave and more merciful than many.

We root for Conan largely because we think what he is doing is right by an externalizeable morality. He is a Bird of Prey that the sheep like and are okay with, even as he encourages them to behave less like sheep.

This is not what the Ubermensch does — the Ubermensch does not gain our sympathy by hewing partially to our values in an antiheroish sort of way — the Ubermensch rises above existing morality and creates new values.

Were we to come across an actual Ubermensch (which, again, is aspirational, not real, but let’s suspend that), we would probably not like him very much, because he would not hew to our familiar beliefs.

As for the analogy of the individual to the mob, I think one of the big points of Conan the Barbarian is that mobs are overrated. You can either lead a mob as sort of a figurehead, part of the institution, and the mob is stoned-ish snake hippies with swords, and while it will appear to be responsible for things that look impressive, it won’t reflect on you as demonstrating real power. You can also lead a mob like Thulsa Doom does, exercising real power over it the way a man swings a sword or fires a snake-arrow at a fleeing horse.

So, the movie compares the power and will that Thulsa Doom uses to command his mob with the power and will Conan uses to just battle people himself, and finds them to be pretty close to equivalent.

Part of my point in writing the article is that, on election day, the difference between the candidate running for office and the individual person voting or working a field office is not nearly as large as it seems — that both might or might not be exercising a certain kind of pragmatic power in the world, depending on how they go about it.

Looking at the American political system this way causes a pretty big discursive discontinuity, though. It doesn’t match up with a lot of the dominant discourse. So you’d kind of have to rework how to articulate and frame phenomena from the ground up.

A shorter way of putting it is to think of the following four things:

Right

Strength

Hindrance

Wrong

Our contemporary bougeoise sensibility relates these things — something being wrong is a big hindrance to doing it. Something being right gives us the strength to do it. We defer to our civilizaton and culture to make a lot of these decisions.

Say there is a sign that says “Don’t climb this tree” — in our bourgeoise sensibility, we would decline to climb the tree, and expect, if we did climb the tree, that we might fall off and break our necks.

The Ubermensch casts aside right and wrong as we know and remakes them. But this doesn’t really address the problem of strength or hindrance

The Ubermensch wouldn’t care about the sign and would decide whether or not to climb the tree just based on his own will — but he might still fall and break his neck. There’s no guarantee he will get up it.

The Flesh in the Riddle of Steel separates these four things into two separate continua — right and wrong on one side, and strength and hindrance on the other.

Conan would consider whether or not to climb the tree, probably brood over it for a little while — we’re not sure what he’d decide to do. But if he decided to climb it, we’d be pretty damn sure he’d get to the top.

I would add, as a TRIPLE POST, that Conan’s ability to climb the tree doesn’t just comes from his physical strength, it comes from what Thulsa calls his “heart.” He has a will and determination to climb the tree that is characteristic of living flesh and not characteristic of abstract institutions or inanimate objects.

This will is distinct from the moral will of the Ubermensch. It is not required of an Ubermensch that he enjoy climbing trees.

Here’s something from the very first Conan story. It’s probably the greatest summary of Obama’s first term ever:

When I was a fighting man, the kettle drums they beat,

The people scattered gold-dust before my horses feet;

But now I am a great king, the people hound my track

With poison in my wine-cup, and daggers at my back.

“When I overthrew the old dynasty,” he continued, speaking with the easy familiarity which existed only between the Poitainian and himself, “it was easy enough, though it seemed bitter hard at the time. Looking back now over the wild path I followed, all those days of toil, intrigue, slaughter and tribulation seem like a dream.

“I did not dream far enough, Prospero. When King Numedides lay dead at my feet and I tore the crown from his gory head and set it on my own, I had reached the ultimate border of my dreams. I had prepared myself to take the crown, not to hold it. In the old free days all I wanted was a sharp sword and a straight path to my enemies. Now no paths are straight and my sword is useless.

“When I overthrew Numedides, then I was the Liberator–now they spit at my shadow. They have put a statue of that swine in the temple of Mitra, and people go and wail before it, hailing it as the holy effigy of a saintly monarch who was done to death by a red-handed barbarian. When I led her armies to victory as a mercenary, Aquilonia overlooked the fact that I was a foreigner, but now she can not forgive me.

“Now in Mitra’s temple there come to burn incense to Numedides’ memory, men whom his hangmen maimed and blinded, men whose sons died in his dungeons, whose wives and daughters were dragged into his seraglio. The fickle fools!”

Man, this stuff is so awesome.

This slightly off topic, but all of this talk of Conan and the Riddle of Steel keeps making me think of the amazing “Conan the Barbarian: The Musical” video:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OBGOQ7SsJrw

Does the riddle of steel apply to apply?

I meant to say “Does the riddle of steel apply to robot”