(Contains comprehensive spoilers for LOOPER)

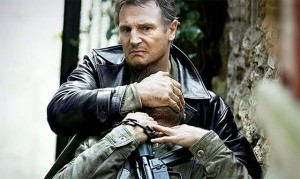

In the 2008 thriller Taken, Liam Neeson plays Bryan Mills, a retired CIA operative. He has spent decades overseas, serving his country, but missing out on his daughter’s life and his own marriage. He tries, ineffectually, to worm his way back into his daughter’s life now that her mother has remarried. But when human traffickers kidnap her in Paris, Mills flies to France, tracks down the baddies, murders them ruthlessly, and rescues his daughter. The movie ends with the family being tearfully reunited in Los Angeles and with Mills giving his daughter a thoughtful gift: private singing lessons with a pop star.

If the plot sounds familiar, it’s because it is. Change the daughter to a wife and you have Die Hard. Change Paris to Pittsburgh and you have Sudden Death. For years, the thriller genre has taken advantage of working male anxiety about the balance between parental responsibilities and employee responsibilities by casting the absent father as a hero. Sure, he wasn’t there to take his kids to ballgames or piano recitals. But he was there when terrorists took over a place. He saved his family’s lives, along with the lives of hundreds of strangers. He had a rich life outside of his household, and his family couldn’t appreciate that until danger made it plain.

I was reminded of this when watching the trailer for Taken 2, screened before a showing of Looper. On paper, they seem like an obvious match: mid-budget action thrillers made by small studios. But two disparate details struck me later.

First, Taken 2 grapples with an issue rarely picked up by action thrillers: the cycle of violence and revenge. Rade Šerbedžija, the industry’s go-to Slav, plays the father of one of the men Bryan Mills killed in Taken (and not even a particularly important victim; a henchman who provided one useful lead and was then electrocuted with alternating current). He swears revenge on Mills for killing his son, then arranges to have him and his family kidnapped in Istanbul. He confronts Mills with his transgressions, only for Mills to respond with a scowl. “Your son kidnapped my daughter,” he says.

We don’t see what happens next in the trailer, but I’ll take a stab at it. I presume Šerbedžija’s character doesn’t say, “Okay, I guess we’re even,” and let Mills go. I presume Mills doesn’t acknowledge that the cycle of violence brought him to this place and accept his capture and eventual execution with good grace. What probably happens is that Mills escapes and uses his “particular set of skills” to kill the brothers, cousins and fathers who came to Istanbul to kill him. If these men have brothers, cousins, or fathers of their own, maybe they’ll show up for Taken 3. Or, if Taken 2 goes the Seventies route and has Mills die in the end, maybe Maggie Grace will suit up and go kill some Albanians in the sequel. “You killed my father,” she’ll yell, and Karl Urban will yell, “Your father killed my brother!”, and gunfire will resolve the accounting.

Action thrillers rarely grapple with the cycle of violence because it’s too reminiscent of real life. We go to the movies for many reasons, but escape is common among them. And the cycle of violence that we recognize in the news – in Eastern Europe, in the Middle East, even in North America – is too depressing to confront head-on. Any attempts to package it in a narrative form, pitching a decades-long war as the fault of one side alone, fail under critical scrutiny. But a movie gives us the luxury of a stopping point. The hero is the one left standing when the credits roll. It doesn’t matter if our hero uses the same methods as the villains: gunfire, knifeplay, maiming and torture, in the case of Bryan Mills. He’s doing it for his family. The cycle of violence ends when he’s finished.

(Absent from all this is the consideration that perhaps the more heroic choice would have been to give up the overseas CIA job and accept a more boring, lower-paying job in the States in order to be with one’s family. But that’s a subject for another post)

So the first point of discord is how rarely any movie grapples with the cycle of violence. The second point was how Taken 2 was a trailer for Looper, a movie which embraces such an uncharacteristic take on the cycle of violence as to almost be a different genre.

Looper, of course, features some very obvious cycles of violence central to its plot (as we discussed on the podcast). A looper’s last assignment is always to shoot himself in the head: his future self, sent back in time to keep illegal time travel a secret. Their ceaseless, anonymous violence claims them in the end. We see Joe’s fellow loopers celebrating this in various montages. While there’s something to be said for the blissful certainty that nothing you do in the next thirty years will kill you, most of us would be more inclined to fear someone who gleefully embraces their self-destruction. Picture Tony Montana at the end of Scarface, taunting the assassins into riddling his body with bullets that he’s too coked up to feel.

But the key cycle, the one that’s only fully explored at the end, is the cycle surrounding the Rainmaker.

The Rainmaker is a man without a past. In a century where “tagging” has become so ubiquitous that corpses have to be sent thirty years into the past to be disposed of, he’s someone without an identity. All that’s hinted at is that he has a synthetic jaw and that he’s taken over five international crime syndicates singlehandedly. We learn, shorty before Joe does, how such a thing might be possible: the Rainmaker is an immensely powerful telekinetic with some unrealized rage issues.

In Looper, there is presumably a primary timeline, where Joe kills his old self, gets paid and lives another thirty years. In this timeline (T1), the old Joe that’s sent back doesn’t survive. Joe kills his old self, moves to Shanghai, and falls in love. The Rainmaker exists in this timeline (we see his name in a scrolling banner on the news). Old Joe overpowers his captors, ducks into the time machine of his own volition, and disarms Young Joe by flinging a gold bar at him. He then sets off to find and kill the pre-adolescent Rainmaker.

It is Joe’s act of hunting down the young Rainmaker that turns him into the Rainmaker: the boy is wounded by an errant shot to the jaw and his mother is killed. Presumably, the young Rainmaker flees to the city, loses his jaw to infection, and swears vengeance against all loopers, a vengeance that he fully realizes thirty years later once he’s taken over all the time travel syndicates. This is the second timeline (T2), in which a time traveler inflicts a different destiny on the present he came from.

But! T2 diverges from T1 not when Joe kills Sara, but when Joe realizes that he’s killed his future self. The Rainmaker exists in the timeline of the young Joe who killed old Joe and then became old himself. Old Joe thinks he can extricate himself from the Rainmaker timeline by killing three kids. But Joe has always been in the Rainmaker timeline. His decision to use violence, not the act of violence itself, is what made the Rainmaker possible.

Both Young Joe and Old Joe think that violence can solve all their problems. Young Joe thinks of violence as a steady paycheck and a lucrative retirement. Old Joe thinks that violence will stop a monster from coming to power. Both reach for it instinctively, like a crippled man does for a crutch. When Young Joe offers Old Joe a way to save his wife without having to murder any children – tell him who his future wife will be, so Young Joe can fall in love with somebody different – Old Joe won’t hear it. Is it because he wants to have his cake and eat it too, and he thinks that violence will let him achieve that? Or is it because he’s so used to violence he can’t trust any other solution?

Old Joe wants revenge on the Rainmaker for sending the thugs who killed his wife. The Rainmaker wants revenge on loopers for killing his mother. The temporal interweaving of these makes them a self-renewing cycle, a perpetual motion machine of violence. Old Joe’s thirst for vengeance can never be sated, because his act of firing at the Rainmaker gives birth to him. And the Rainmaker can never bring his mother back, because his act of sending loopers back in time for self-execution puts Old Joe in a position to shoot her.

In Looper‘s climax, Young Joe realizes this. He sees that every act of murder creates not only a corpse but a wronged party: a widow, an orphan, a mourner. Young Joe, an orphan himself, is a product of such violence, and of course he reached out to violence – Abe putting a gun in his hand – as a solution. He passed that lesson on to Cid, while hiding beneath a trapdoor waiting for the gat-man to leave the farmhouse.

So what is the answer? The only answer is to remove oneself from the equation entirely. Not just disarm, but accept loss. Stop thinking of death, justice, and vengeance as things that a person can deserve, or things that a person can earn through violence. Young Joe learns this, at the point of a blunderbuss, and not only rights the death that should have happened thirty years in the future, but improves the world by preventing a Rainmaker from coming to power.

If you want to understand just how subversive a message that is, apply it to Taken. Bryan Mills learns that his daughter is kidnapped and about to be sold into sex slavery. It would repulse us to suggest that he do nothing, especially when the first act of the movie makes clear that he’s very capable of doing something. But his act of “doing something” generates more widows, orphans, and mourners, all of whom operate on the same principle he does and come hunting for him in Taken 2. In the course of saving his daughter, he may have doomed himself – and, depending on Šerbedžija’s thirst for vengeance, his daughter may still be in trouble. The net effect of his violence is not just zero, it’s likely negative.

Yes, of course, the Albanians are evil and Bryan Mills is good, so it’s wrong that they take vengeance and right that he does. But the desire for vengeance is an emotional urge, and while we may deny our villains access to the narrative desserts that our heroes get, we never deny them the same set of emotional responses. Villains feel joy, sadness, and anger, the same as our heroes do.

(Also, the good/evil dichotomy slips a little when Mills tortures a man through electrocution, then maims an innocent woman to compel an answer from her husband)

The idea that violence can be a force for good is such a dominant discourse that it takes a bizarre narrative to not only examine it but stake a real challenge against it. It takes a time travel story so complex that it might not even be diagrammable (where did the first old Joe, the one Young Joe kills, come from?). It takes an action thriller that literally pits a man against himself, racing against the clock to shoot himself in the head, only to realize he has to shoot himself in the chest.

But that is one of the chief virtues of science fiction, as we mentioned on the podcast: its ability to turn metaphorical tropes into literal phenomena. We have a world where the existential question of survival in the face of inevitable death confronts us every day (The Road), or a planet that forces us to confront our subconscious fears (Solaris), or a battle with our future self over the right to use violence. The fact that we need such a fantastical concept to even address this challenge should suggest that there is no easy answer.

Personally when I heard Taken 2 would have the family of the people he killed has vilain, I immmedialty though “Well if always has to kill the family of everyone related to the people he previously killed how many movies will be needed before before Liam Nesson wipe out Albania population”

Good article, and great movie (Looper, that is. Haven’t seen the Takens). You’re missing something important, though, that in my own overthinking, has led me to a theory: Sara’s son is NOT the rainmaker.

We are all but told outright that he is- he has the right birthday, at the right hospital, has immense telekinetic powers, and, as Joe realized at the ending, was about to grow up, alone, hating Loopers, and with a jaw “presumably lost to infection.”

Now, as the movie tells us, this time travel stuff will melt your brain, but try to stick with me. Using your own system (for simplicity), we are shown two timelines during Looper. We shall dub these T1 and T2.

In T1, Joe successfully closes his loop, moves to Shanghai, loses the love of his life to the Rainmaker’s violence, and travels back in time to prevent her death from occurring- by killing the Rainmaker as a child.

In T2, Joe from T1 arrives back in time, and escapes his own execution. He sets out to murder three children- knowing that one among them will become the Rainmaker, but not knowing which. When he arrives to kill the third child- Sara’s son, the telekinetic- he is stopped when T2 Joe realizes that T1 Joe’s violence causes the Rainmaker, and then kills himself.

So here’s the problem: we are told that Joe from T1 killing Sara creates the Rainmaker. But in T1, Joe closed his loop- he lived happily in Shanghai. It is implied these events loop around forever- but we are only shown two loops. There was no T0, no third Joe, to kill Sara in T1- the loop was closed, Joe collected his gold, and moved to Shanghai. In T1, the timeline Bruce Willis’ Joe came from, the Rainmaker *should not exist*.

Hopefully I explained that well enough, because I’m going to move onto the second half of my theory: we can see that without T0, there was never a cause for Sara’s son to become the Rainmaker, meaning he should have never existed in T1. Unless, of course, Sara’s son wasn’t the Rainmaker.

He is an immensely powerful telekinetic, but that’s circumstantial evidence at best. Rainmaker isn’t rumored to have any sort of powers like that- he’s done the impossible, but it’s never said he used TK to do it. He also has a very specific birth day and place- shared by only two others.

Joe from T1 killed the first child. Sara’s son, the third child, has been ruled out. That leaves the second child- the child of Joe’s stripper/romantic interest. On his way to kill the second child, T1 Joe is captured, fights his way out through the mob, and heads straight for Sara’s farm.

Only three children have the birthdays and place given. One is killed by T1 Joe. One is, inversely, never harmed by T0 Joe. The third, however, presumably lives well into the future. The son of Joe’s girlfriend caused his murder, the murder of his future wife, and the entire cycle of violence? Very fitting, if you ask me.

Now for the caveats- the following are also equally possible explanations.

-Sara and T2 Joe were wrong. Her son grows into the Rainmaker with or without her.

-The information given to T1 Joe is inaccurate. Either it points to something OTHER than place and date of birth, or was simply outright mistaken.

This is some solid Overthink! It grapples with issues I picked up and discarded in the post (e.g., where does the first Old Joe come from?). So I hate to overlook it entirely.

But: the movie makes it really clear that we’re supposed to conclude that Cid is, or could become, the Rainmaker. It doesn’t give us any indication that there’s an alternative explanation. Yes, doing the math on the timelines exposes some unresolved holes, but that’s not a math that we should be doing in the theater with the lights down.

(That said – this is such a good summation of the intricacies of multiple timelines that I don’t want it to pass without commendation, especially on this site. So: nice work!)

My thought on that question (“where does the first Old Joe come from?”) is that there’s one stable time-loop where Old Joe never happens to meet the love of his life, is thrown into a time-machine properly tied and hooded, and is immediately killed by his past self.

In the movie, the love of a woman* seems to be consistently presented as the thing that can mess with all sorts of cycles: self-destruction, revenge, and stable-time-loops engineered by the mob.

* Old Joe’s wife for Joe, Sarah for Joe, Sarah for Cid (initially averted), Joe’s mother for Cid (averted). And it is always women, even the examples of parental love (present or discussed) are all mothers. Any inkling that Young Joe might have been able to use his money to save Suzie and be somehow redeemed that way is also averted (he raises the possibility, she rejects the offer as nice but absurd). The movie’s begging for feminist analysis. (Googling for some produced this, which is pretty good.)

I think Cid was the Rainmaker. And I like how that neatly sets up Joe as both someone who could solve and someone who could perpetuate that cycle of violence.

In T1, Cid becomes the Rainmaker because Sarah never reconnects with him. In T2, Young Joe (because of Old Joe) inadvertantly saves Cid by getting Sarah to reconnect with him. Which means that Old Joe, in trying to break the cycle of violence through violence, would just be perpetuating it. (Also a dramatic reversal of what happened in T1, where Old Joe inadvertently fixed things for himeself until Young Joe’s decisions ruined everything again.)

As far as I can recall, Old Joe only talks about the Rainmaker’s artificial jaw when he’s already in T2. That’s after time-travel is already messing with his mind, after his memory (of stuff that has not yet happened to Young Joe) has become a blur of future possibilites. Old Joe’s discussion about the Rainmaker is as much about what could happen in the future of T2 as what did happen in the future of T1. That’s key to Young Joe’s realization of how things could go down at the end of the movie, he realizes that Old Joe’s description of the Rainmaker is as much about his (Young Joe’s) potential future as it is about Old Joe’s past. That’s the point where Young Joe really internalizes that he and Old Joe are (on some fundamental level that Young Joe hadn’t accepted before) the same person. And that’s what gives Young Joe the insight he needs to make his decision.

(As someone who loves the narrative structure of tragedies and stories with time-travel in them, I thought Looper was just an amazing, amazing movie to over-think.)

The real answer, as far as I can tell, to “where was Old Joe in Timeline 1” is actually pretty simple. Remember when Sara revealed she knew about Loopers? Loopers, by necessity, have to be secretive. After all, if the government outlaws time travel in 30 years and it’s common knowledge that future crime syndicates have time travel, the government can be more pro-active in shutting them down totally. So why does she know about this?

Answer: Other Loopers have already tried this and failed.

Now, we see Cid blow up a Gat Man in the movie, and we know he blew up his other mother (Sara’s sister). We also see ex-Loopers, in the future, collecting and passing information about him. So, presumably, there were Loopers coming for them before Sara came by, and maybe one or two afterwards. They were, obviously, stopped before, either by Sara’s sister, Cid or Gat Men, but they had encountered them before.

Now, PERHAPS Old Joe and Young Joe’s actions did stop the Rainmaker. After all, Sara does seem to have a bit more of a “killer instinct” now that her little boy has actually gotten injured by one. Also, Old Joe did kill a few young Loopers in that big shootout at Abe’s base. However, the depressing fact of the matter is that Young Joe’s sacrifice may have been in vain, because the Looper who would eventually kill Sara may not have been amongst the dead in Old Joe’s shootout, and may not have actually come yet.

Abigail Nussbaum makes a good case for where the T1 Rainmaker came from without the influence of the Joes; that Looper has a theme of how people’s choices are limited by their circumstances and their paths in life are only changed by the influence of others. So in T1, and backwards to T0 and beyond, the Rainmaker comes about because Sara fails to breach her son’s armor of contempt. It’s only in T2 that Young Joe alters their relationship’s dynamic, giving them the ending’s ray of hope.

(where did the first old Joe, the one Young Joe kills, come from?)

While Looper’s time travel rule are fairly elastic, like with the arm carving appearing in real-time but not retroactively being known or influencing the traveler, there seems to be a sort of constraining influence that prevents little changes from cascading into tremendous ones — like nuclear war, for example. Even once Old Joe (T1) starts living in Young Joe’s (T2) timeline, he still has the possibility of still meeting his future wife. The Rainmaker has a synthetic jaw, even if it’s not due to Old Joe shooting him. Within a given loop, events persist. Old Seth (T1) always escapes from Young Seth (T2), even after his legs were retroactively chopped off and rendering him unable to run away. But in a hypothetical next loop (T3), the now-mutilated Old Seth (T2) couldn’t sing a song or run away, and would be killed by his past self.

But time travel can screw up the timeline tremendously, even if there’s a minimal iron clad proof against, say, a Looper somehow causing a nuclear war. Seth is proof of that; T0 Old Seth was killed as planned by T1 Young Seth, but T1 Old Seth hums to his past self (T2 Old Seth). Presumably, Old Joe becomes responsible for the Rainmaker’s lost jaw when previously he was just another Looper loose end to be cleaned up.

Can Young Joe’s suicide end the Rainmaker’s terror before it starts? It’s uncertain. The movie certainly gives us a vague sense of hope, and, as Nussbaum notes, only other people can have a positive effect on others, and Young Joe is a new element in T2’s Rainmaker’s chain of events. Yet there’s also a lingering sense from these loops that certain things are predestined thanks to the time travel.

I can see why this movie’s world banned time travel immediately. Even if you take the sort of extreme precautions the mob did to make the loops “self-cleaning,” at some point in the nigh-infinite iterations of those loops the situation will go straight to hell. There are probably endless timelines where Old Seth and Old Joe died according to the plan, as occurs in the loop where Old Joe (T0) was involved, but the movie we see takes place in the particular iteration where circumstance leads to the plan going haywire in the extreme. Young Joe’s timeline (T2) has the extreme circumstances of his suicide, as well as Old Joe (T1) completely destroying the past’s time travel mafioso.

There are actually at least 4 timelines in the movie, of which 2 are depicted.

T1: There is no time travel until it is invented in the future.

T2: Jeff Daniel’s character is sent back in time and hires Joe.

T3: Old Joe is sent back and killed by his younger self, he then grows up and falls in love in Shanghai.

T4: Old Joe is sent back and escapes being killed by his younger self.

The Rainmaker exists in T3, but may or may not in any other timeline. Therefore Old Joe killing his mother cannot possibly be the event that caused him to go evil.

Great article, though I take issue with one of the bits at the end:

“Yes, of course, the Albanians are evil and Bryan Mills is good, so it’s wrong that they take vengeance and right that he does. But the desire for vengeance is an emotional urge, and while we may deny our villains access to the narrative desserts that our heroes get, we never deny them the same set of emotional responses. Villains feel joy, sadness, and anger, the same as our heroes do.

(Also, the good/evil dichotomy slips a little when Mills tortures a man through electrocution, then maims an innocent woman to compel an answer from her husband)”

I think there are two issues with this:

1. Mills isn’t out for vengeance – he’s out to save his daughter. While that doesn’t necessarily excuse his conduct, it’s a very different moral equation when you’re dealing with prevention of harm than when you’re dealing with the punishment of wrongs that are in the past. (It’s why the police can shoot you if you pull a gun on an innocent bystander, but aren’t allowed to shoot you if you’ve already shot them.)

2. The Albanians aren’t just bad because they’ve kidnapped Mills’ daughter, they’re also bad because they’re going to keep kidnapping OTHER people’s daughters. While it’s clearly not Mills’ goal to prevent future kidnappings (he makes it clear that he’d stop if they’d just give him his daughter), his conduct has that effect – in the immediate aftermath of the first movie, it’s safe to say that there is a non-zero number of unkidnapped tourists that would otherwise be kidnapped and sold into sex slavery.

In that light, I’m not sure that the good/evil dichotomy isn’t justified in this example. Maybe it should be “Not Good” vs. “Evil, but Mills’ conduct is wrong in a way that is qualitatively different from the evil of the Albanians in Taken 1. As for the Albanians in Taken 2, unless we choose to believe that they didn’t know why Mills had killed their kids, then it’s pretty tough to justify their “revenge” claim either (in the same way that we wouldn’t justify the revenge taken on a police officer in my example from #1).

This is a fair point.

I hint at my issues with Taken‘s morality – and, in turn, the morality of most 90s/00s action thrillers – in a throwaway comment earlier:

(Absent from all this is the consideration that perhaps the more heroic choice would have been to give up the overseas CIA job and accept a more boring, lower-paying job in the States in order to be with one’s family. But that’s a subject for another post)

I should probably give this its own post. The idea that a man will go through gunfights, explosions, and bloody beatings to prove his love for his family is a common trope; the idea that a man will go through drudgery and a 45-minute commute to prove his love, less so. Yet the former is seen as heroic and the latter as mundane, despite the fact that the latter inflicts far less collateral damage.

Because of that, I don’t find the fact that Mills murders to save his daughter a compelling balance (and I inaccurately phrased it as a quest for “vengeance” because of this). He cares about his daughter now that he’s all but lost her; what about for the first eighteen years of her life? It almost feels like a pretext.

Of course, I may not find it compelling, but I still get the same “fuck yeah!” in my gut when I hear Liam Neeson growl into a telephone. That’s part of the appeal.

I’m with Ben – Taken isn’t a revenge movie. Mills has one objective and that is to get his daughter back. I don’t think we’re supposed to feel like Mills is unqualified good, or even on-the-balance good. Like you mention, he tortures a man past the point of information-gathering and shoots an innocent woman to get what he wants. That blurring of the lines shows that Taken is subverting, at least a bit, what you seem to be claiming it triumphs.

On the other hand, Kill Bill is a revenge movie. And the cycle of violence is clearly acknowledged when Beatrix kills Vernita Green in front of Vernita’s daughter and then invites her to take her own revenge at some point in the future. Beatrix is aware of the cycle of violence, knows that she is perpetuating it, and accepts that as a necessary condition for achieving her goals.

This is probably just me being silly and imagining things, but one of the things that struck me when watching looper, almost to the point of distracting me from the film, was how very much the crime boss sent back from the future (Jeff Daniels’ character?) looked like everyone’s favourite (in-?) famous professional movie overthinker Slavoj Zizek, a likeness that was (again, probably just in my head), hammered down further by those snarky metacinematic comments he gave the other mobsters early in the film.

From then on, perhaps because I’ve been reading a possibly unhealthy amount of Zizek lately, I couldn’t help noticing how readily the themes in Looper seemed to lend themselves to overhinking along (my admittedly poor understanding of) Zizek’s Hegelian-Lacanian ideas; the movement from one timeline to another trying to break the cycle of violence felt a lot like the working through of Hegel’s dialectics, there was (as noted above) the theme of a woman, or the absence thereof, as a traumatic kernel destabilising the symbolic order, I suppose one could put the good ol’ Oedipal spin on the relationship between young an old Joe and the idea of getting rid of one’s problems in the present by sending them back to be brutally killed in the past seems an amusing inversion of how psychoanalysis retroactively explains present symptoms by past trauma, etc etc

Someone could definitely write a good piece on this, and at some point I might even try to do so myself, although that will at least have to wait until the film comes out on dvd, so I can give it a closer look.

In the meantime I’m just putting these rather confused thoughts out here.