First, let’s get one observation out of the way: Batman: Arkham City is the best Batman video game since Batman: Arkham Asylum, which at that point was the best Batman game of all time. It is the best simulation of what it should feel like to be the Dark Knight, Gotham’s only hope against hordes of insane criminals. You solve mysteries using cutting-edge gadgets, you swing and glide from the rooftops, and you take on thugs in packs of thirty at a time. It’s like a grown-up version of the 90s classic, Batman: The Animated Series, even featuring many of the same voice actors (Kevin Conroy, Mark Hamill, etc). If you like Batman, get this game.

So that’s the gameplay and the atmosphere. What about the story?

Well …

[WARNING: there’s no way for me to do justice to this article without spoiling the entire plot of Arkham City, so I’m going to do that now. The game is still playable, and even enjoyable, if you know the entire storyline, but consider yourself warned.]

So: Quincy Sharp, fresh off the success of his stint as warden of Arkham Asylum, runs a successful campaign for Mayor of Gotham City. His first major act is to wall off an entire borough (including a museum and the old police station) and turn it into a giant open air prison. Armed guards patrol the skies in choppers, while Gotham’s master criminals war for territory. Weird psychiatrist Dr. Hugo Strange has been placed in charge of the prison.

(All the above is prologue, by the way, spelled out only through indirect references)

Bruce Wayne holds a press conference calling for an investigation into abusive practices within Arkham City. He’s arrested and thrown inside the walled prison. But this was all a clever ruse to get Wayne inside, where he changes into Batman and sets off on his investigation. Of course, Dr. Strange already knows that Bruce Wayne is Batman, and taunts him privately with this knowledge before boasting that he will soon put “Protocol 10” into effect.

Batman tracks down the Joker, hoping to learn from him what Protocol 10 is. Joker is dying from the TITAN-enhanced Venom derivative that he used in Arkham Asylum, however. He injects Batman with a sample of his blood in a surprise attack, forcing Batman to hunt down a cure. Mr. Freeze had been working on a cure, so Batman goes to rescue Freeze from Penguin.

Freeze claims that the cure won’t work without a serum derived from blood with regenerative properties. Batman reasons that Ra’s al-Ghul’s blood might work, and trails one of his assassins to a secret hideout. Talia al-Ghul, Ra’s daughter, invites Batman to undergo the “Trial of the Demon” to prove his worthiness to replace Ra’s; Batman accepts, defeats Ra’s, and swipes a sample of his blood.

Freeze uses Ra’s blood to engineer a cure, but Harley Quinn steals the last sample before Batman can take it. Batman fights Joker and his goons, but is pinned beneath rubble as Dr. Strange initiates Protocol 10, bombarding Arkham City with rockets. Joker is about to finish Batman off when Talia appears, offering Joker a chance at immortality. The two of them leave together.

Batman gets free and infiltrates Strange’s tower. He learns that Ra’s Al-Ghul was Strange’s benefactor shortly before Ra’s kills Strange. Strange initiates a self-destruct in the tower control room, forcing Batman and Ra’s to jump out; Ra’s dies in the fall.

Joker sends a message to Batman, saying he’s taken Talia hostage. Batman goes to save her, only for Talia to overpower Joker and kill him. But the Joker she “killed” is in fact Clayface, masquerading as a healthy Joker. The real, TITAN-infected Joker shoots and kills Talia. Batman then defeats Clayface, retrieves the cure from Talia, and ingests enough of it to cure himself. Joker tries to swipe it from Batman, but the vial shatters. Batman carries Joker’s body outside the walls of Arkham City and delivers him to Commissioner Gordon, before returning to the prison to continue cleaning it up.

Does that look ridiculous to you? Because it’s twice as ridiculous when experienced live. But let’s ignore the Joker subplot for the moment and focus on Dr. Hugo Strange.

Ra’s al-Ghul approaches Dr. Hugo Strange, tells him that Batman is Bruce Wayne, and provides him with the funding to help Quincy Sharp get elected Mayor [UPDATE: a commenter reminds me that Strange actually approaches Ra’s, not the other way around. I think this makes even LESS sense, but that’s what the game gives us]. Quincy Sharp then creates Arkham City out of some old Gotham neighborhoods and puts Strange in charge. Once the place is full of prisoners, Strange initiates Protocol 10, which is an order to murder every prisoner inside the walls. This is all part of Ra’s al-Ghul’s master plan to cleanse the world of corruption and return it to a “natural” state.

A few questions arise.

First: is this the best use of Ra’s resources? He’s a genius with the wisdom (and the patience) of having lived for centuries. If he wanted to isolate criminals or purge Gotham, he could have come up with a dozen slower and subtler means. What’s jarring about this plan is how rushed it is: Sharp gets elected Mayor and immediately starts building a fortified outdoor prison.

Second: Protocol 10, the insidious master plan that Strange has been alluding to ever since Wayne set foot in the prison, is “murder everyone”? That’s not a plan; that’s a tantrum. And there must have been easier, or less public ways, to do it. Why not introduce poison into the water supplies of existing prisons, like Blackgate? Why herd all of Gotham’s violent criminals into a brand new, highly visible prison and then order choppers to strafe them?

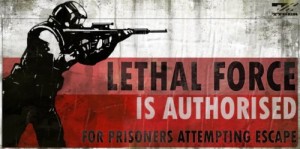

And finally, and most importantly: who would go along with this? Conditions in Gotham have always been depicted as bad, but is the city so plagued by crime that citizens wouldn’t object to turning an entire neighborhood into a penal colony? A penal colony with harsher rules than any existing American “supermax” prison, where transgressions are met with lethal force? Where inmates are left to openly war with each other? This is a Burmese level of fascism happening on America’s East Coast, and apparently it takes mere months to ramp up.

One might say that Arkham City is a commentary on the way democracy can slip into fascism: by electing tyrants to power, by targeting classes that no one cares about, and by paring down civil liberties at the margins. That’s a valid story, and one worth telling. But in Arkham City, democracy doesn’t slip into fascism so much as gallop. Gotham goes from a recognizable American city to a police state overnight. The people of Gotham don’t elect a tyrant: they elect a buffoon backed by a mad scientist, who is in turn backed by an immortal warlord.

Nothing about Arkham City is subtle. But then, nothing about superhero comics has ever been subtle.

Whenever superhero comics try to get “edgy” and “real,” they bump against the limits of the genre. Superhero comics are meant to have action and thrills. That’s why people read them. So when a writer introduces a problem in a comics storyline, it has to be a problem that can be solved through thrilling action.

I first noticed this in Warren Ellis’s Stormwatch (though Ellis wasn’t the first writer, and is hardly the only one, to suffer from this). When Ellis picked up the Stormwatch line, one of the first multi-story arcs he introduced was an American military conspiracy meant to kick Stormwatch, the U.N.’s superteam, off of U.S. soil. There certainly were fringe conservative groups in the 90s who believed that the U.N. was consolidating its power into “one world government” (black helicopters, Illuminati, etc). But in Stormwatch, Ellis uplifts these groups into a coherent, competent, punchable foe.

And then punches them.

We see similar absurdities with the X-Men storylines from the early 80s. Chris Claremont used the persecution of mutants as an allegory for social treatment of subaltern classes (e.g., race relations, sexual preferences, etc). On rare occasions, this meant debating tolerance with depth and passion (e.g., God Loves, Man Kills). Most of the time, however, this meant wild-eyed Senators signing the latest Sentinel Production Act, in which giant laser-shooting robots would fly around the country and kill or capture mutants. Why these giant robots were never put to use addressing the Marvel Universe’s many other super-threats (like the Skrull or Doctor Doom or the Mandarin) remains a mystery. But it gave the X-Men the ability to fight against social intolerance by blowing shit up, which is always fun.

And most recently, we had Marvel’s Civil War storyline. A super battle that causes massive civilian casualties results in a proposed Superhuman Registration Act. The superhero community is split down the middle on the merits of government licensing: some see it as a necessary safeguard, others as an unconscionable crackdown on civil liberties. There’s a deep and important story to be told about that dilemma. Unfortunately, Civil War didn’t tell it. Instead, the pro-registration side creates an extra-dimensional prison to hold refuseniks and clones an Asgardian god to fight on their side, while the anti-registration side started picking fights with the Feds.

Superhero comics are rarely a good medium to talk about real-world issues. Why is this?

Superheroes themselves, depending on who depicts them and who you ask, live on a spectrum between “adolescent wish fulfillment” and “four-color depiction of Jungian archetypes.” Either way, though, superheroes are hard to imagine as people per se. Superheroes, by their nature, transcend the problems you and I suffer. When you’re stronger than anyone else in the world, or faster, or have sharper senses, or even just unerring logical accuracy, a lot of conventional limitations fall away.

Of course, a sophisticated superhero story will still depict the limitations that these invincible beings suffer. Superman can’t have a regular relationship with Lois Lane, and neither his heat vision nor his impervious skin will help. Iron Man suffers from alcoholism and serial philandering, driving away the people who humanize him. And even Batman has lost people close to him.

But these all-too-human limitations are just narrative obstacles that hinder the superhero’s ability to do what he’s meant to do: punch aliens, catch falling buildings, and shoot bad guys. Clark Kent never decides that the world can save itself (or that the Justice League can do the heavy lifting) if it means he can have a normal relationship with his wife. Tony Stark never decides that it’s the pressures of leading the Avengers that’s causing him to drink so much. And these aren’t unreasonable choices – real human beings make these decisions all the time! Hell, “give up your career to be with the one you love” is one of the most popular dramatic tropes in the 20th century.

Superheroes are colorful world beaters first, humans second (if at all). This hinders their ability to grapple with human issues.

Next, comic books, as an evocative, visual medium, give more weight to evocative, visual solutions than to prosaic ones. Comics feature images and text, but the images tend to be far more memorable. Everyone remembers the dying Superman cradled in Lois Lane’s arms; no one remembers the text in the pages leading up to that moment. So if you have a problem in comics, it had better be a problem someone can punch.

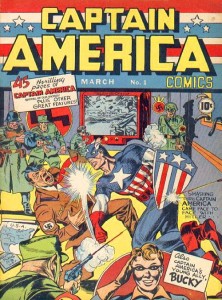

Take that, you Ratzi!

(This is one of the many reasons why Watchmen is a work of transcendent, deconstructionist genius: Ozymandias tries to solve a real-world issue with comic book methods)

The difficulty, of course, is that so few real world problems—if any!—can be solved by punching the right people.

Consider prison and asylum reform, a subject that Arkham City addresses in passing. Dorothea Dix spent over a decade railing against cruel treatment of the insane. State hospitals for the insane were the exception, not the norm, prior to her investigations and her crusades. She fought to establish state hospitals in Massachusetts, Illinois, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. It took her from 1840 to 1853 to accomplish this much, and none of it would have been made any easier by punching President Franklin Pierce in the jaw.

Rev. Louis Dwight popularized the Auburn System around the mid-19th century: a penal methodology that encouraged rehabilitation through labor. It was considered an improvement on the Pennsylvania System that it gradually replaced, in which inmates were cloistered in private cells at all times and forbidden to speak with each other. Of course, the Auburn System also enforced silence during group activities and allowed for a lot of corporal punishment that we would consider inhumane today: flogging, for instance, or soaking a prisoner under a deluge of icy water. It took nearly fifty years for the Auburn System to fall out of favor, as popular sentiments toward corporal punishment changed. Again, a problem that required extensive trial and error, not punching.

Now consider Gotham City, or specifically Arkham City. Bruce Wayne considers Arkham City abhorrent. What might he do to get it shut down?

- Finance a documentary film crew to interview guards, inmates and released prisoners;

- Bankroll a reform candidate for Mayor;

- Buy up the Arkham City contract (presuming that, like many large prisons in the U.S., it’s privatized) and appoint his own administrators;

- Spearhead a campaign for eminent domain reform: that’s a lot of land that Gotham City must have bought up to build an open-air prison.

And so on. But what does Bruce Wayne actually do?

- Sneak inside, punch people in the mouth.

As a cautionary tale on real-world abuses of power, Batman: Arkham City is disappointing. But in this way, it’s no different from other comic book depictions of real-world issues, like racism or isolationism. In the comics, these problems are solved whenever the hero punches the villain in the face. And since the greatest strength of Arkham Asylum and Arkham City has been in how they translate the comic book experience into a video game, this level of absurdity may just be part of the plan.

Mr. Perich, you article reminds me of this reflection of Superman’s effectiveness:

http://www.smbc-comics.com/index.php?db=comics&id=2012

But on a more serious note, I think it’s important to ask why Bruce Wayne chooses to punch things rather than attempt some sort of political or legal reform of this broken system. In short, I believe it’s because his parents are dead. At length, I believe that unless a certain level of social corruption and endemic crime is allowed to exist in Gotham City, there would 1) be no outlet for Bruce Wayne to satisfy his unquenchable thirst for vengeance, and 2) people would have legitimate grounds to question any reliance on vigilantes like Batman if the police are actually good at doing their job.

I just want to go ahead and nominate this right now for the year-end poll regarding best article (I assume being an occasional guest writer gives me that authority, right?). Seriously though, this was a brilliant piece. The explanation of why comics book heroes solve problems the way they do makes perfect sense, and was one of those cases where I had all the pieces, but just never put them together into a logical conclusion.

One other note, by summarizing the plot of Arkham City, it becomes fairly obvious just how much it was written simply to move the game along. Of course, this is true of almost all games to a certain degree, but it does seem a bit more blatant here. It’s as though half of the plot points serve little purpose other than to stretch out the game. As I read it, more and more of the summary started to sound like this – “Freeze creates the cure, but then Harley Quinn steals it in order to make the game a little longer”.

…still an amazing game though, and an Overthink that is just as good.

Brad: I’m with you. I’m getting a little frustrated on games that stretch out the narrative by simply kicking the can further down the road each time you get close. Batman needs a cure: Mr. Freeze has it. Mr. Freeze is in the police station – nope, Penguin kidnapped him. Penguin’s in the museum – oops, you can’t get in until you blow up three signal jammers. And so on.

Good article.

In terms of the plot of AC, I think it was half good. The joker stuff was all great, and the relationship between him and batman was well done, the whole co-dependency thing cleverly shown literally through the disease. The clayface trickery was a fantastic ending as well, and joker’s death was really well done. Freeze and penguin just about held their elements in this side of the plot too

The Raas a ghul side of the plot was, to me, not well done. When we initially encountered him, his level felt like an irrelevant aside, and his whole persona didn’t fit in with the AC vibe. The whole Wonder City concept was a bizzare bit that was bonkers in a bad way, and the whole aesthetic of the level felt like a crappy version of bioshock’s visual style. The chemisty between Batman and Talia also sucked, and whilst she was used well in the finale, it would have been even better if she was a more interesting character, that we cared about.

When Raas was shown to be behind the whole H Strange thing, it felt very tacked on. It seemed that the writers could have put any villain that thinks they’re doing good into that position, but because we had seen him before, they thought they may aswell just thrown Raas in there. And it is also very true that a character that was supposed to be as clever as he was would not use such a stupidly convoluted method of criminal killing.

I have far too much to say about the plot, but I’ve already rambled alot so I’ll stop.

[Side note; this game pronounced the name of Raas differently to how I thought it was. ‘Rashe’ instead of ‘Rars’ Is this how it should be?]

The thing with AC’s plot that I couldn’t get over is that it opens with a paramilitary group abducting a prominent billionaire on national television and detaining him without trial or charges as a political prisinor in some sort of crazy super-supermax facility. I guess if you’re cynical enough about the national security apparatus and ignore the fact that Bruce Wayne is probably a platinum-level political donor, I guess you could imagine some future president sanctioning this; but it’s all happening at the behest of a goddamned municipal government. How is Arkham City not under siege by every federal law enforcement and military agency imaginable? Yes, yes, suspension of disbelief but it was just too far.

Fine points and all but there’s a couple plot points the article actually got wrong. In the last chunk of the game Ra’s reveals it was Strange who came to him with Batman’s identity; not Ra’s. This is where I get confused. In the comics both Ra’s and Strange figure out Batman’s identity independently. Strange figures it out through a lengthy (and psychotic) trial and error process filled with medical experiments and mad scientist antics, whereas Ra’s figures it out by ruling out who would be wealthy, resourceful, smart and skillful enough to be Batman (seriously, in his first appearance he explains all this in a paragraph. Its nuts. Makes you wonder whether everyone in Gotham is just dumb or have they huffed one-too-many Joker gas fumes?) However they don’t explain the way either of them figured it out.

Yet even if we assume Strange just figured out Batman’s identity at random and planned this whole thing out; how did he find Ra’s? Its presumed he ran into him abroad doing “evil scientist things.” My major point is that someone knowing his identity is supposed to be a big deal (even though the comics have sort of dialed this down ALA Batman INC) and a little bit more plotting might’ve been nice, even though I personally really liked each section on their own merits (Mr Freeze’s section being a highlight for me.)

Jsorell: thank you for the correction! The game is pretty stingy with its exposition, and, like you, I was similarly confused between the game’s version of who knew Bruce Wayne and the comics’ version. So I think I conflated the two in my head when writing the article.

I guess part of this as well is making a real issue (horrible prison conditions) into a cartoonish exaggeration of itself, where the wardens are literal supervillains, which negates any kind of political statement. Of course, sympathy for criminals would destroy the whole visceral thrill of Batman anyway…

A lot of the visceral thrill of Batman is from how close we can sympathize with criminals, with how tight we walk that wire without falling into the abyss. Batman doesn’t kill but saves the Joker, and the most entertaining set pieces usually go to the villains.

Is it how the subject was exaggerated or just exaggeration at all negates a political statement?

Now, to be fair, the plot opens with Wayne trying to publicly shut down Arkham City peacefully, and then he is abducted and forced into the prison. While the game claims this is all part of his plan, it doesn’t discount the possibility of successfully shutting it down with public pressure if no abduction occurs.

That said, I think that Batman/Wayne could come up with better peaceful methods to stop Arkham City than a public protest. This is the same Batman (Well, not actually because the video games don’t claim continuity) that got Lex Luthor to reopen Gothem after No Man’s Land while still defeating his property stealing scandal.

Without having played the game, I don’t know how valuable anything I have to say could be. However, I do think there’s something to be said about the different roles I assume some of the characters take on.

*Freeze just so happened to be working on the cure, and ends up being the tool. The fruits of his labor get taken. That’s kind of lame. He’s a better character than that. Cheesy, but better.

*The Joker is more like Mr. Freeze- he’s trying to find a cure, although sure, he’s cool (hah!) with having a little fun along the way. That’s not entirely unsatisfying, but could be better. And at least he still seems to be the main mover of the plot, even if he didn’t instigate things. That’s fine by me. Mark Hamil as the Joker is always a joy.

*Ra’s? I suppose he’s pretty much in character. So is Harley Quin, for that matter. Both seem to be “doing what they do,” so to speak- Ra’s saving the world in his roundabout way; Quin being reduced to nothing more than a sex object with no desire other than to serve the Joker and no purpose other than to advance his storyline (I base this assumption on the images I’ve seen of her from these games, as well as what I know of her character in other depictions). Ra’s, then, is rather meh. Quin, that upsets me. Another character that could be done better, but I think she suffers frequently from being watered down and reduced to a toy in myriad other places; so while she’s true to form, I’ve never found the form satisfying. It would have been revolutionary if she had had, I don’t know, her own motivations.

*No idea about Penguin. Was he planning on selling the cure or something? Seems like a kick of the can, pure and simple. Unsatisfying, and reminds me of the third X-Men movie and the barrage of random mutants that were name-dropped in a whirlwind of let’sseehowmanycharacterswecancraminhere that made no sense.

*Talia is also a tool. Also mostly true to character, from what I know (although she’s the character about which I know the least), but still somewhat unsatisfying.

*Strange is the chaotic sociopath, the masochistic and psychotic guy that doesn’t need any real motivation, other than simply, “Because.” Which, when done right, is utterly terrifying. If keeping within the Batman genre, he’s actually more like extreme depictions of Joker (I’m thinking The Killing Joke, or, if we include non-comics, Nolan’s version of the Joker is the best one here). His purpose is to tap the ball and make it roll, but why he taps it is of little consequence. And this is the most unsatisfying of them all- the entire sequence of events is based on the random fickle feelings of a maniac. This may happen in the real world (which goes back to your piece more concretely, John), but in fiction, that’s frustrating and often gets called “bad writing.” It’s scary, but it’s still not very fulfilling. I guess I like my Batman stuff to be fleshed out.

I think what makes the true-to-form characters unsatisfying as such is how convoluted all their links come across as. Granted, I’m just going off this article and what my friends with the games tell me (I’m in grad school and know I’d flunk out if I actually got a PS3 or Xbox). Having them go through the motions in a sort of relay race to the end just feels empty.

I would be interested to see the relationship between Batman and Joker more fleshed out, as in if I got to play or watch someone else (so then I may as well do it, since Lord knows I wouldn’t be able to do any sort of multitasking if that was on the screen). If there was ever a graphic novel that wrenched at me, The Killing Joke did, I think more so than Watchmen. On the meta-level, just contemplating the symbiotic nature of the two of them on its own, outside any “context” of a specific comic, game, movie- it’s kind of tragically beautiful.

/end rant

Also, tangent,

The tangent was supposed to be about the rumors that Nolan’s movies were supposed to fit in with these games.

Also, I’ll add that the really intense scene in The Dark Knight Returns between the Joker and Batman (you’ll know what I mean if you’ve read it) haunted me for days.

I think you miss the real point. The real point and appeal of comic books is this:

1)We are all consciously or subconsciously aware of the fact that many of society’s problems,for all the talk and blather, DO generally come down to a people or group of people who are causing it all. (For all the BS about societal issues, the ultimate cause of violent crime in your neighborhood is the violent criminal—- aka the shitheel who thinks other people’s money, property and lives are up for grabs.)

3)We are bitterly aware of the fact that “the proper methods” of dealing with these horrible people (talking, legislating, debating, “going through the system,” and yes, more talking) aren’t stopping them. Worse, those tools of the system are often being used AGAINST us by the very people we wish to thwart. We pass laws, they are broken or overturned. We sign petitions, they are ignored. We press suits, the decision is made against us…. or is made for us, but the penalties are whittled away to nothing by obfuscation, delay or appeal.

4)We also know right down to our bones that BEATING these people into a coma would both solve the problem and provide much needed stress relief.

Problems ARE solved with fists. Also with guns, bombs, tanks, ships– it is the reason that cannon were labeled “the last argument of kings,” “peacemakers,” “diplomacy carried out via other means….”We no more desire that “final argument” than anyone. The adulation of superheros is the desire of people to see the bullshit set aside and the issue rectified WITHOUT turning the community at large into a crater-filled graveyard.