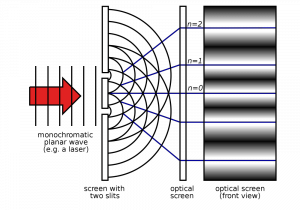

Quantum physics is full of strange conclusions, demonstrated by the “double slit experiment.” In it, you set up a screen with two narrow slits and a light sensitive detector on the other side. When you shine a light on the screen, you get a distinctive interference pattern on the other side.

The conclusion is that light is a wave, cancelling itself out in some places and reinforcing itself in others. The strange part is that you get the same interference even when the light is so dim that only a single photon is released at a time—implying that the single photon passing through a single slit is somehow interfering with itself on the other side. The mathematical explanation of the result is (relatively) straightforward, but physicists have been deeply divided on what the strange results really “mean” in a deeper sense.

There are two dominant, competing interpretations of quantum theory: the Copenhagen Interpretation and the Many-Worlds Interpretation. Grossly oversimplified, the Copenhagen Interpretation says that the strange results of quantum mechanics don’t correspond exactly with reality. Instead, quantum theory is a product of probability and the limitations of observation—in essence, the strange result is left strange, and if a particle wants to act like both a particle and wave, then that’s just the way it is.

The many-worlds interpretation, on the other hand, argues that the interference is really caused by the interaction two different universes. In one universe, the particle passes to the right; in another, it passes to the left. Because those two universes are so close together, they can influence each other, and we observe the interference pattern. The implication of this argument is that the universe is constantly splitting at every conceivable point—that we exist in a multiverse where there is a universe corresponding to every conceivable configuration of quantum states.

Combining the many-worlds interpretation with a theory of quantum mind is known as the “many minds” theory, and it implies that our mind is really the result of many different minds spanning multiple universes interacting and interfering with one another. In Inception, the subconscious, dreaming mind, could be open to leakage these other universes—Cobb compares the dreaming and creative process to “discovering” new worlds. Viewed through the lens of the quantum mind and the many-worlds interpretation, that’s exactly what is happening: when you dream, your mind is open to all of the senses and experiences of another world, exploring another universe for the night.

This means dreams are not just the product of random neurons firing while you sleep. Rather, they are fragments of real experiences from counterpart minds throughout the multiverse. The people you meet and places you go in a dream are as real in their own universe as you are in your own; you’re just experiencing a tiny snippet of that reality. This provides a solution to the dilemma of exponential communication between minds in the shared dreams of Inception. The communication doesn’t have to take place entirely within just one universe, so it’s not restricted to the tiny IV line connecting the participants.

When Cobb tells Saito that they have become “Old men, filled with regret,” the machine doesn’t have to somehow compress and speed up Cobb’s words 160,000 times and send them across an IV line- the two minds are already experiencing the same universe, talking to each other through the air just like in ours. Seen in this light, the shared dream is a feat of navigation, not computation—the dream machine only has to transfer enough information to keep the dreamers “moving” between universes together, ensuring that their minds are open to the same location in the multiverse.

This explanation accounts for several differences between the shared dream of Inception and the natural dreams we experience at night. Natural dreams are erratic jumbles of experience, constantly skipping from place to place. In a natural dream, you are exploring the multiverse by yourself, so there’s nothing preventing random jumps from universe to universe. In a shared dream, though, there are multiple participants, holding each other back from constant changes in perspective. All the participants have to travel in lockstep, so the dreams are more stable from moment to moment. Ariadne asks how you can create a world so detailed that it feels real, arguing there’s no way you could keep all the textures, tastes and sound in your head. Given a multiverse, though, the universe they experience can be fully realized, with the texture of the universe filling itself in automatically.

When you dream at night, you only experience what’s right in front of you. In the shared dream, on the other hand, the projections of Fisher’s subconscious persist, fighting and dying even when Fisher is asleep in another room, experiencing a whole other world. Because the shared dream is rooted in the multiverse, his subconscious mind doesn’t have to constantly check up on and control dozens of projections, driving snow mobiles and shooting guns at people in hotels. Instead, Fisher’s subconscious navigates the group to a universe in which his projections already exist. Once there, the projections act on their own without constant supervision from Fisher’s brain. All of the people and places in the dream exist and persist naturally, without any additional computational demands on the dreamer.

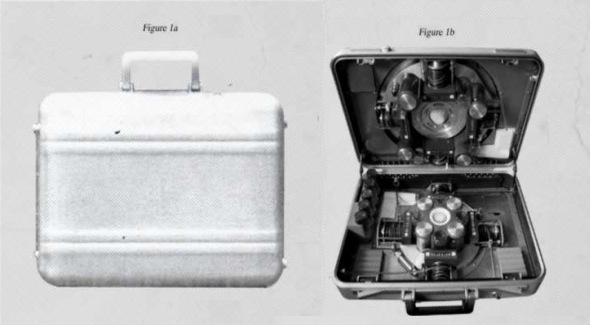

The characters never mention the multiverse or quantum mechanics. It’s likely that they don’t know how the machine works. And for good reason: the machine was built by the military so soldiers could learn how to kill by stabbing and shooting each other. The implication of the quantum theory of mind and the multiverse is that the people you meet—and kill—in the shared dream are every bit as real in their universe as we are in ours. The inner workings of the machine would be the most closely held military secret, for fear of soldiers balking at killing their fellow soldiers, even in another dimension.

The existence of a machine with the capabilities shown in Inception would act as proof of the “many minds” theory, which could have profound philosophical implications. The many-minds theory has always been closely tied to the theory of quantum immortality, which argues that from an internal perspective, death is impossible. If your consciousness has access to the entire array of universes containing it, there will always be at least one universe in which you’ve beaten the odds and survived. Your consciousness is bound at every “branching” of the universe to follow a path that avoids death.

Imagine placing yourself into a chamber, with a device that takes a quantum measurement every few seconds. If the spin of the proton is up, you die – if the spin of proton is down, you live. Regardless of how many times the experiment is run, there is at least one universe where you are still alive, where every measurement has been of a “down” proton—from your internal perspective, your consciousness can only exist in “down spin” universes. Inception’s director, Christopher Nolan, has played with this idea before, and even constructed a “quantum suicide” device in The Prestige: Hugh Jackman’s character never knows if he’s going to be “the man in the box,” but there will always be at least one version of The Great Danton alive at the end of the Transported Man.

Note, however, that the perception of immortality only exists for the individual. You can’t experience your own death because your consciousness can only exist in a universe where you’ve survived. From an outsider’s perspective, however, there’s still a 50-50 chance of existing in an “up-spin” universe where you die. This explains the bizarre nature of death in the shared dreams of Inception. When a character “dies” in the shared dream, they cease to exist in the universe the rest of the participants are experiencing, but the sedative prevents them from waking and returning to their original universe. Having lost the tether to their “real” universe, they slip into the “raw, infinite subconscious” of limbo, navigating freely through the multiverse, “creating” or “discovering” the world as they go- but in doing so, losing the anchor that allows them to wake and return to their original universe.

Mal is consumed with the idea that her world is not her own, with the question “What if your world is not real?” In the Matrix, where the dream-world is the construct of a computer simulation, this question is all important. The good guys all choose the “red pill“ of reality. Even though the real world of Zion is a bleak, hopeless hell-scape of constant warfare, there’s little doubt that we’re meant to prefer it because it’s “real.” Only the cowardly Cypher prefers the ignorance of life in the Matrix, lured by the promise of all the steak he can eat.

Mal is willing to risk death to get to the “real universe”—her leap of faith is Inception’s version of the red pill. But in the world of Inception, to share a dream is to share a universe; the dream is just another location in the multiverse, every bit as real as our own. In Cobb’s final confrontation with Mal, she tries to convince him that he doesn’t really believe “in one reality anymore.” When the credits roll and Cobb’s totem is still spinning, he has already turned away, gone to greet his children. Faced with the fact that the dream universe can be every bit as real as our own, he’s decided that it doesn’t really matter whether or not the top stops spinning. He’s finally arrived in a universe where he can come home to his children.

Ben Adams is a Naval Officer living in Southern California who should probably be using his time more effectively. When he’s not driving warships or fighting pirates, he maintains his own blog, Think Like a Fox.

Great post! It went a little off the rails on the second page from physics into meta-physics, but who cares since this site is about thinking outside the box and having fun!

I don’t want to ruin it, but if you have not already you must read Neal Stephenson’s “Anathem”. It’s a massive book, but I couldn’t put it down, and if you are as interested in this subject matter as you sound, you won’t be able to either.

Nice calculations. I know understand quantum theory better.

I accept the lady in the red dress as an example, but technically, she was created by a computer programmer(mouse) for a training program outside of and separate from the matrix.

The Matrix does not run at a 1:1 ratio with reality during bullet time.

If your dreams are real, then parents will no longer tell their children that they were just dreaming. All your worst fears will be true.

While the brains in inception are used as meat-computers, I am aware of no link exists to connect the minds.

Fascinating stuff, and a thoughtful meditation on an entertaining idea. Like Jack Donaghy, I don’t sleep on planes because I don’t want to get incepted.

I would say that if the many worlds/minds theory is to hold up, we need to find an explanation for the very specific effects of movement in “higher” worlds on “lower” worlds, how the inhabitants of those worlds can be trained to defend the secrets of the “surface” world, and why our world (or perhaps the “surface world” of the movie) isn’t plagued by kinetic interference or murderous secret-snatchers from similar worlds for whom we are presumably a dream-scape.

Also, regarding The Prestige – I always took it that Danton absolutely knows that he’s going to be the man in the box. He just also knows that he’s going to be the man on the balcony.

Great post. A subtle but profound way to look at the logic of Inception — that it’s not an inner psychological architecture, but a cosmic metaphysical one, full of “reality nodes” that the machine bridges between.

Also interesting: if you’re talking about the dream-spaces being multiple worlds, you don’t actually answer the question of “Why can a character experience a year in one universe, but only live for ten minutes in another?” The only plausible answer I can think of is that these multiple universes are chronologically unhinged from one another, and don’t have even remotely analagous timelines.

TIME in this scenario would work like SPACE in the Narnia series — there’s a specific moment in time (or a “window,” if you will) that acts as an entry point. Once you enter that new universe, you have complete access to the parallel space, with no real physical or temporal boundaries. However, you have to return to the same entry-point… the same drug-induced 10-minute window… that you used to cross the threshold in the first place. So that very short window of source-time opens up a great deal of virtual time, just like the very small real-world space of The Wardrobe opens up the very large virtual space of the Land of Narnia.

I know that didn’t all fit together perfectly. The point is… there is no fixed quantitative ratio of “virtual time” to “real time”… just two universes, each working through its own timeline, linked by a narrow reference-point in the source universe, activated by the Pasiv Device.

Interesting read. Under the assumption that the “many minds” theory is true, in the sense that you describe it, what are the implications of death to people in the “real” world? When you are dreaming you have access to the multiverse through your subconscious in its dream state. However, you do not have access when you are awake. Perhaps this is the reason why those who have a natural death (old age, etc.) are asleep when they die. It is the consciousness’s fail-safe. It creates the bridge to the multiverse so that it can continue existing. However, if you die while awake (gun shot to the head, etc.) the fail-safe does not have the capability of activating, and the consciousness ends, this “soul” dies completely. The implications of this theory would be huge. If you were capable of mastering your mind in such a way that you could control the subconscious and consciously navigate through the multiverse, almost like lucid dreaming but control enough to become lucid at anytime not just after observing a dream, you could become immortal. It would be the meta-physical fountain of youth. You are awake in universe 1 and death is inevitable. Before the bullet strikes, you instantly put yourself into this lucid dreaming state and navigate to universe 2 via the multiverse connections established by the subconscious. The bullet strikes in Universe 1 and your body dies. However, your consciousness was locked in Universe 2 in the body it created as a means to interpret your presence there (i.e. your body in a dream). The ties to Universe 1 are severed the consciousness survives in Universe 2. You continue living as the person you were in Universe 1, however you are now living in an entirely different Universe. Repeat this at death in Universe 2 (and 3 and so-on) and you become immortal.

A counter to this argument is what Jesse M brought up about Narnia. We can only perceive time and space as linear. However, if time and space is planar than it is very possible to the travel through a Narnian universe for years on end and return back to your universe without any time passing. Almost as if your connection between the original universe and Narnia were a portal locked at a specific time in the original universe once it is opened. To tie in to the the above example, we may be able to consciously navigate to universe 2 through a lucid state and we may return back to universe 1 only to be killed by the bullet because time never continued. But, if we tether the universes together by means of keeping a piece of our consciousness within Universe 1 so that both universe 1 and 2 can chronologically advance together, we then may be able to survive in universe 2 after the bullet strikes our body in Universe 1, but we may be diminished. However, the fragility of the consciousness is unknown, it may be able to continue in the diminished state, or it may be destroyed if it is not whole. But, since knowledge of, and memories of Universe 1 are the tether, it is possible that the consciousness will continue only without the piece that tied it to Universe 1. So, we will technically be immortal through the persistence of our consciousness, however everything that made that consciousness “ours” will be gone. (This is why there aren’t immortals walking around, you fall asleep before you die but the part of your consciousness that remained in Universe 1 was your memories. The consciousness exists, but you do not.) Thus, in order to become immortal, we would have to discover a way to tether the two universes together with something that does not define who we are. With that ability, true immortality would be possible.

As for navigation through the multiverse, I believe this would be accomplished through brainwaves. In inception, the sedative may operate in such a way that those put under dream at the exact same brainwave pattern. And thus, matched with their proximity, are capable of sharing dreams. If this were real, then through music (binaural beats) and sedatives (tailored to the individuals normal brainwave states), we could precisely match the brainwaves of groups of people and allow them to navigate through the multiverse together and share dreams. I assume proximity would be necessary because the location of your bodies would create the portal to other universes. If people are close together, and operating at the same brainwave pattern, then they will enter the multiverse together, close to each other. The reason you don’t share dreams with your spouse when you sleep together is because you are not operating at the same brainwave pattern. The reason you don’t share dreams with strangers, whose brains are operating at the same brainwave pattern, is because you are not close enough to each other to meet in the dream multiverse. Thus, I believe that dream sharing is only possible if the two dreamers can create the exact same brainwave patterns and sleep in proximity to each other. This could be testable with the right equipment.

I’ll just point out here that the vast majority of physicists spend very little time thinking about the “meaning” of quantum mechanics. It works, it makes testable predictions, and it allows us to do our jobs.

This is in no way criticizing this interesting piece of overthinking, or overthinking in general, just reassuring anyone who doesn’t want to lose sleep over what quantum mechanics implies about the fundamental nature of human existence. Physicists aren’t laying awake at night, so you don’t have to either (unless you want to).