[Check out this guest post by Alicia Aho, Potterverse fans! – Ed.]

A pretty girl and her friend are playing in a quiet spot some ways from home. Unbeknownst to them, they are being spied on by a male figure in the bushes. At length he emerges — the friend shrieks and runs away, but the pretty girl holds her ground, even though she’s frightened.

This is how Odysseus meets Nausicaa in Homer’s Odyssey. It is also how Severus Snape meets Lily Potter in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows — perhaps the only YA fantasy ever to open with a quote from Aeschylus’ Libation Bearers:

Oh, the torment bred in the race,

the grinding scream of death

and the stroke that hits the vein,

the hemorrhage none can staunch, the grief,

the curse no man can bear.

But there is a cure in the house,

and not outside it, no,

not from others but from them,

their bloody strife. We sing to you,

dark gods beneath the earth.

Now hear, you blissful powers underground —

answer the call, send help.

Bless the children, give them triumph now.

Once you start looking for ancient Greek parallels in Harry Potter, they show up everywhere.

Harry lives in a world described by prophecy and teeming with creatures pulled from classical myth: centaurs, spirits, basilisks, phoenixes, hippogriffs, and three-headed watchdogs. Circe and Mopsus appear on Chocolate Frog cards. Even the Sphinx makes a cameo appearance in Goblet of Fire.

On a more technical level, many of Rowling’s central characters have epithets, words or phrases that grow stronger with repetition until they attain an iconic resonance. Athena in the Iliad and Odyssey is often described as grey-eyed; in much the same way, Harry has green eyes — specifically, his mother’s eyes. There is Voldemort’s high, cold laugh and Dumbledore’s half-moon spectacles.

But it’s in the themes of Harry’s story that Rowling is most powerfully in debt to Greek epic and tragedy. The classical framework illuminates two otherwise puzzling aspects of the Potter universe: what is the significance of blood, and why is there no sense of religion in the wizarding world?

The Blood Paradox

Let’s start with the death of Dumbledore.

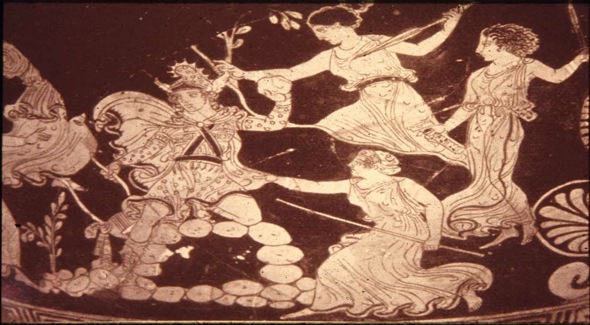

To anyone familiar with Greek literature, Dumbledore’s funeral may as well have featured a witch on a broomstick writing CHTHONIC HERO in ten-foot letters across the sky. A king or champion is laid to rest, and the grave makes the land hallowed and uniquely powerful. Dumbledore’s white marble tomb, with the pyre set alight by a phoenix and the appearance of centaur archers, is the same as the funeral of Hector, who died defending his towered city; the burial-place of Oedipus, old and wise, who makes victorious the land that accepts his body; and especially the sacred tomb of murdered Agamemnon, where the victim’s children plan their revenge.

Which brings us right back to The Libation Bearers.

The lines Rowling lifted from Aeschylus makes it plain that blood is both a curse and a cure, miasma and numen. The children of Agamemnon have a dilemma: if shedding kindred blood is evil, then how are they to take vengeance on the mother who slew their father? In one way, Harry’s problem is simpler: he does not have to choose between his parents. But he still must find a way to defeat an enemy with shared blood in his veins, blood that has been hallowed by Lily’s sacrifice.

To make things more complicated still, in the wizarding world there is a tension between the idea that Muggle-born wizards are no different than pure-bloods (meaning blood is unimportant) and the fact that Harry’s mother’s blood is his most powerful defense (meaning blood is hugely important).

What that Aeschylus quote helps illuminate is that it is not the purity of blood that matters, but what happens when blood is spilled by or for someone else.

Of all Rowling’s characters, Dumbledore best understands that blood’s great power does not come from some innate quality, but in blood’s ability to bind people even beyond the bounds of mortal death. Voldemort, on the other hand, fundamentally misunderstands this power of connection, as Dumbledore explains to Harry:

He took your blood believing it would strengthen him. He took into his body a tiny part of the enchantment your mother laid upon you when she died for you. His body keeps her sacrifice alive, and while that enchantment survives, so do you and so does Voldemort’s one last hope for himself.

– Deathly Hallows

Voldemort’s mistake is to think that shedding the blood of others will increase his power. In fact, it increases his enemies, as many of Voldemort’s victims have families and loved ones whose grief motivates their struggle against him. As in Aeschylus, there is a moral imperative to avenge a slain or injured relative. It’s as though kindred blood-ties become more activated by violence. This is why Narcissa Malfoy undermines Voldemort’s plans, why Neville refuses to join the Death Eaters and slays Nagini, why Aunt Petunia’s blood is capable of protecting Harry during all those summer breaks between books.

In this context, we can see the phrase ‘blood traitor’ as a red herring. Being related is nothing: all the pure-blood families are related, we are told. It is the spilling of blood more than the sharing of it that matters in the wizarding world. To shed blood by murder or to die in someone’s defense are both far more potent acts than simply existing in the same kindred network.

And this same connective power of blood allows Harry to be guided by those he has lost. In both Goblet of Fire and Deathly Hallows there are scenes where Harry is surrounded and supported by his dead parents and other victims of Voldemort. Both scenes also involve the shedding of blood: Cedric Diggory’s death and several jarring deaths during the Battle of Hogwarts. This is a remarkably clear parallel to the nekuia in the Odyssey, where Odysseus pours out blood for the dead to drink while he converses with them.

The blood link is Harry’s greatest asset against his nemesis. It is also the key to Rowling’s moral universe.

Where Do Bad Wizards Go When They Die?

Harry Potter is surrounded by the dead — the ghosts at Hogwarts, moving photographs and portraits, resurrected spirits, loved ones lost, and memories experienced in the Pensieve. And yet, aside from one conversation in Order of the Phoenix, very little is said about the afterlife. Capital letters are implied: when they die, wizards Move On to Some Other Place in the Beyond. There is no discussion of wizard heaven or wizard hell, or what Harry would have to do to end up in one rather than the other.

And really, should there be? Saintly behavior would not bring Harry’s parents back. Voldemort’s darkness will not be conquered by the shining purity of our hero’s spotless soul. Such an idea would diminish the agony and sacrifice of every wizard who fought him before Harry’s birth and afterward. And those sacrifices, Lily’s in particular, that define the ethical framework in which Harry grows up.

Because of his mother’s murder and the protection it gives him, Harry is both innately opposed to Voldemort’s brand of evil and uniquely positioned to fight it. Two decades of spilled blood cry out for vengeance, a palpable debt that only grows heavier as the series progresses. What Harry needs is not a list of abstract rules for virtue – witness the horrible absurdity of Dolores Umbridge’s I must not tell lies – but a concrete, practical sort of goodness. Harry constructs an ethical system around courage, loyalty, and altruism as an explicit response to his enemy’s cowardice, cruelty, and narcissism.

It’s pretty clear (in most cases) when a witch or wizard is good or evil, courageous or craven. And that moral status indicates something very substantial: whether or not the witch or wizard in question can be relied upon for help in battle. Good and evil actions have echoes not in the afterlife, but in the living world. Kinship is created out of a shared struggle and blood spilled for a common purpose. The Death Eaters have their brand, and Harry and his friends have their scars.

The greatest possible moral metric is how a witch or wizard copes with death. Lily Potter threw herself between her infant son and his would-be killer, even though she could have escaped with her life. Dumbledore engineered the precise circumstances of his death to protect as many people as possible for as long as he could. In contrast, Voldemort feared his own death so much he tried to kill a one-year-old boy. In a world predicated on courage and self-sacrifice, this is indeed the ultimate evil.

At the end, Harry bravely faces death — precisely the same death as Lily’s. “I’ve done what my mother did,” he tells Voldemort in Deathly Hallows. “They’re protected from you.” Harry’s reenactment of his mother’s sacrifice succeeds because he intends to die. And what he finds is not an afterlife, but a crossroads: he can Move On and be at peace, if he likes, or he can return and make certain that his enemy is conquered.

Harry chooses to go back and fight. There’s nothing more classically Greek than that.

Conclusion

This reading is not intended to suggest that Harry Potter is a pagan throwback completely free of Christian themes. (Because we could have a pretty long discussion about faith and martyrdom and Harry/Dumbledore/Snape, if that sounds fun!) But it is astounding to look away from the Christian lens and see Rowling borrow from classical texts to build a credible, complex system of ethics without reference to the rewards or punishments of the afterlife. It is marvelous to read a story where life and death really, deeply matter in this world and not the next.

Voldemort’s great weakness, as Dumbledore tells us, is that nobody’s death matters to him but his own. The great strength of Harry and the other heroes is that they feel death’s power but do not fear it. They shed blood on behalf of those they love and defeat evil. They find the cure in the house.

Alicia Aho never uses one sentence when there’s room for a second. She also writes historical romance under the name Olivia Waite.

[Does Harry’s triumph over Voldemort break the cycle of death and vengeance? Will the Furies create a new form of government where the muggles can exert influence over wizards, like they did at the end of The Eumenides? Sound off in the comments! – Ed.]

“(Because we could have a pretty long discussion about faith and martyrdom and Harry/Dumbledore/Snape, if that sounds fun!)”

It does.

I thought so too. Harry is supposed to trust Dumbledore, who trusts Snape. How far out should trust be extended by this transitive property?

Ah, this is reminding me of when J.K. came to Open Morning at my high school, and many a starstruck student hyperventilated as she passed – but not so a friend from my Latin class, who barged straight up to her and demanded a litany of classical influences on Harry Potter. A happy memory.

Does your friend from Latin class know that Harry Potter has been translated into Latin? It’s really good, actually — though the scene from the first book where the snake escapes to Brazil? In Latin, a talking snake is terrifying.

Yes, my teacher gave some of it to me to translate, and one year for Christmas I got a copy of “Winnie Ille Pu”. All those books translated into Latin are brilliant for friends and family of classicists who are stumped for a present!

Actually, I had the most fun with Asterix in Latin, and the world’s most adorable five-year-old who asked me to read it to him (no translation required). His parents told me he was an absolute classics nut, and that he’d named his puppy Hector after his favorite Trojan hero. Bless.

The Orestaea in its entirety is all about familial blood debt- recall that the house of Atreus was cursed because of Tantalus’s cooking up of his own kids; one of Clytaemestra’s motivations for killing Agamemnon is his sacrifice of their daughter, Iphiginia; Orestes is eventually convinced to avenge his father’s death because of the father-son blood connection; and the furies go after him because avenging the death of his father involves the shedding of his mother’s blood. Orestes is actually in a really rough position because either way, familial blood debts loom around him. On one hand, if he doesn’t kill Clytaemestra, the death of his father goes unanswered for, and allowing the death of kin to go unavenged is bad. But to avenge that, he has to kill his mother, thereby shedding familial blood with his own hands- a terrible thing to do, too. But I digress…

I’m curious about something, then. Myrtle was Voldy’s first victim- which fits well with your (I think correct) assertion that the shedding of blood in the Potterverse in itself is more important than whose blood gets shed (and the circumstances are important as well- as in people shedding their own out of sacrifice v. shedding that of others out of selfishness). She was, after all, a muggle. But his second victim was his father. And his pseudo-justifications for it are similar to some of those Clytaemestra has for killing Agamemon, as in the loyal wife is abandoned and treated poorly by the husband, etc. But overall, and again, this isn’t out of touch with your own arguments, those characters focusing on blood content are the ones that ultimately find defeat- the drive for “pureblood” strength loses, while loyalty to those shedding their own blood with like purposes wins the battle. The interesting thing is how important both kinds of blood ties were to the ancient Greeks in the epics and plays- see above rambles about the Orestaea. But at the same time, the male heroes of Homer and the tragedies are often “blood brothers” because they have shed the blood of common enemies (or at least were trained to do so, such as with Orestes and Pylades, as a result of common upbringing).

Not really sure where I was going with that, but your (awesome) piece made me think about it a bit.

Glad you liked the article! And you make some lovely points yourself. I definitely think there are some strong parallels in both stories about violence being passed down through the generations (Weasleys vs. Malfoys, for instance). And of course the fact that Voldemort’s second victim was his own father shows his disregard for blood ties and family structures. He can’t stand being in any hierarchy where he’s not at the top — hence patricide as a rejection of ancestry. I guess that makes the Death Eaters his self-created, dark-side family.

And now I’m imagining them all having Thanksgiving dinner or something and it’s making me giggle a bit.

Lattimore?

I guess she really is taking the place of Tolkien/Lewis in fusing classical and Christian themes in children’s literature. I must give her more credit. Her prose and its repetition did not summon Homer for me before.

A very well done article!

Great article! The ending gave me nostalgia/nerd chills ^^

As for the Classical framework of Harry Potter, what are the tragic flaws of the main actors? If we take Harry to have fallen victim to his own hubris before (and was brutally punished for it by the death of Sirius), the fact that this disposition of his doesn’t repeat itself isn’t quite of his own making, is it?

After all, most of the events of DH unfold according to plan masterminded by Dumbledore, out of his keen awareness that Harry’s, er, enthusiasm needs to be curbed – as Hermione, and later he himself, points out. The plot of DH is drawn out on account of all the hurdles that had to be thrown in Harry’s way.

On that account, is Harry’s decision to go back and ensure Voldy’s demise a counterpoint to the usual tragic flaw which the protagonist cannot outgrow, a sign that over the course of the books his recklessness has grown into mature courage?

Or has Harry simply not outgrown it at all, and only lives a peaceful life in the end because there are no more Evils to vanquish? If so, does Harry turn to gambling, drugs and extreme sports once he hits mid-life crisis, desperate to once again find the thrill of his youth until only The Most Dangerous Game gives him the excitement he craves?

On an unrelated note, the names of many characters obviously point to the Classical framework of the play, but has something been said on the virulent anti-Frenchism of the works, along the same lines?

To take it one step further, if HP is actually the tale of the correction of Harry’s tragic flaw, does it follow that Rowling is limiting her Classical ethics within Christian boundaries? Not Odysseus but Paul, so to speak. Because Classically speaking, it strikes me that the whole point of tragic flaws is that they are unconquerable – for Harry to overcome his makes this a narrative of redemption and ultimately grace.

Personally, I tend to stay away from the concept of the tragic flaw — it makes me look at things in overly simplified ways. (Though this may just be a flaw of my own. Tragic flaws — they’re contagious!)

But I very much like Joel’s point about a classical world with Christian limitations. I do believe there’s a redemptive arc to Harry’s character, especially in contrast to Sirius, who has many of the same unfortunate impulses and never seems willing to grow out of them.

As for the epilogue — I feel as though there will always be evil in the wizarding world. Grindelwald came before Dumbledore, and I seem to recall there are other evil witches and wizards mentioned over the course of the series. Power will always be tempting. Harry still has obstacles — just not ones so intimately connected with his own life, perhaps.

The other thing to consider – I think you alluded to it briefly – is the fundamental place of self-sacrifice in Rowling’s moral universe. So whereas bloodshed does motivate vengeance, like in Aeschylus, the difference with Harry Potter is that it is a comedy. War in Homer or even Virgil (to a lesser extent) is entirely futile, if glorious – the rage of Achilles is spent with his own death, Hector’s children are thrown from the conquered battlements, and father-like Aeneas founds Rome on the blood of a defenseless man. We know how Orestes ended up – even in Sartre, who likes Orestes, it’s pretty depressing. But Rowling’s war, which is predicated on the good guys submitting themselves to being murdered, ends with marriages not murder.

Thinking of Grindlewald, if Rowling revisits the saga, I’d like her to address the implications that he is responsible for/connected to the Nazis

To quote Harry Potter wikia ‘Over the years, Grindelwald raised an army and began a reign of terror that spread through several European countries, though he never attempted to take power in Britain for his fear of his former friend, Dumbledore, who was “a shade more skilful” than he was.’ This part always made me think of the occupation of France, Belgium, Netherlands etc. but Britain never being taken.

Furthermore, from the same source, ‘Grindelwald seems to be the wizarding version of Adolf Hitler. The date of Grindelwald’s duel with Dumbledore coincides with the downfall of Nazi Germany. Grindelwald adopted an ancient symbol as his symbol (the symbol of the Deathly Hallows) just as the Nazis adopted the swastika, itself an ancient symbol. Furthermore, the prison Nurmengard shares a similar name to the Bavarian city of Nuremberg, where war criminal trials of former Nazis were held. Nurmengard’s dual role as prison to both the victims and later the perpetrator may be a reference to Nuremberg’s dual significance in World War II, which, aside from being the site of the Nuremberg Trials, was also the site of the proposal and adoption of the Nuremberg Laws, infamous discriminatory laws against Jewish people. Nurmengard also bears a sign that reads “For the Greater Good”, which may correspond to the infamous “Arbeit Macht Frei” sign (German for “Work Makes [Man] Free”) which hung above the entrance to Auschwitz. Grindelwald’s eventual sole imprisonment in his own prison is possibly a reference to the fate of Rudolf Hess, who from 1966 until his death in 1987 was the sole prisoner of Spandau prison.’

The question is whether this is simply analogical or if in the Potter universe the two events and movements are linked.

My mind? It’s boggled.

(Hey Tim. Big fan of your podcast featurings ;))

I’m reminded of something that was often discussed in Vampire: The Masquerade. One of the most fascinating pieces of world-building within was an account of the lives of Vampires throughout human History, written by a Tremere, and annotated by a Tzimisse (sp?). The Tzimisse elder at one point muses that he has seen humans commit acts of far greater cruelty than he or his kindred ever have, and that the parrallel history of magical beings need not be the underlying causes of whatever humans do; rather, there are moments of chaos (macro-conscious, cosmic or whatever) that affect worlds secret and open alike.

I think it would be a little silly on Rowling’s part to have Grindelwald strongly tied to the 3rd Reich, even though a parallel certainly is made. So I like the “general chaos” theory a little better.

That’s a fascinating idea, that there’s some united human undercurrent, a Jungian universal subconscious affecting both magical and Muggle.

And, inevitably, have you checked out Psycomedia if you enjoy the featurings?

Oh hey, now I have! :D

In Harry’s case I think it’s a flaw that cuts both ways – his hero complex may have led to Sirius’s death, but it also pushed him to make the sacrifice enabling the victory of the good guys later on. I kind of like this redemption element brought in, and I suppose his last words before the epilogue (“I’ve had enough trouble for a lifetime”) may point to his “cure” so to speak.

But the importance of self-sacrifice I like very much, and I would disagree just a tad with Joel: Rowling’s war ends with a spade of marriages, okay, but the use she makes of self-sacrifice is one that is tied to a very, very common trop in all of fiction: Good will prevail because Good is ready to do certain things Evil is not; the question, as often, doesn’t become “Will Good prevail?” but instead “What will Good have to lose to prevail?”.

Now okay, Harry doesn’t bite it permanently, and neither do Ron, Hermione, etc. But Dumbledore certainly fulfills his ObiWan role in that respect. And think of Lupin – oh god I had forgotten about Lupin. Fuck you Rowling. Seriously. Someone hand me tissues.