(Enjoy this guest article by frequent contributor Trevor Seigler.)

Francois Truffaut, during his film critic days, argued that in order to appreciate any kind of artist you had to experience his or her entire body of work. You can argue the merits of, say, sitting through every Michael Bay film or reading every J.D. Salinger book not named The Catcher in the Rye, but he has a point: each work that an artist completes reflects their mindset at different times in their evolution from apprentice to master. You have to take the bad with the good if you want to appreciate the artist behind it all. It can be a daunting task, however, if your particular artist subject left behind or is working on an extensive body of work. So film-making seems the most obvious art form for this kind of serious, single-minded survey, as some directors’ body of work can be viewed over the course of a week or two or even a few hours.

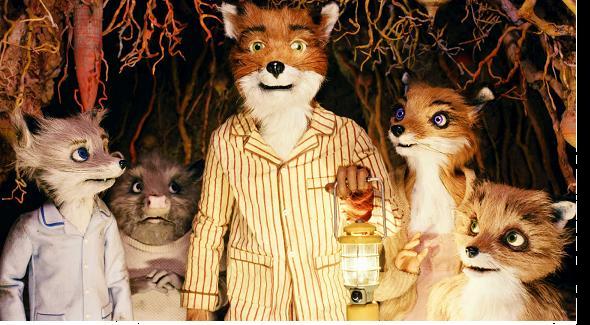

Recently, I managed to complete the Wes Anderson School of Film-Making by renting and watching (and enjoying) The Fantastic Mr. Fox. There was some discussion at the time of the film’s initial release as to why Anderson, a gifted filmmaker whose previous works tended to skew older, would make a kiddie movie.

I wondered what took him so long.

Wes Anderson is, in my estimation at least, one of the more important filmmakers of our current era stateside (Tarantino, Kevin Smith, and Judd Apatow being the others). His first feature came out of nowhere almost fifteen years ago, and he’s produced a series of films comparable to Robert Altman’s in terms of their stylistic unity, unique subject matter, and cast of recurring supporting players (Bill Murray being the most obvious). But what’s interesting to me is how he’s managed to inject adult-themed films with adult-themed material with some measure of childlike wonder and naivety. If I had to choose whether to classify his films as “for adults only” or “for adults and certain sensitive, ahead-of-the-curve-emotionally-and-intelligence-speaking kids,” I’d have to go with the latter.

There is a stigma attached to filmmakers by those in intelligentsia that they make only movies for mass consumption (when was the last time you heard positive critical reviews of a Uwe Boll film?), but there’s the danger of being so artistically challenging that you can’t even find a loyal audience amongst the people that would otherwise embrace you. Often, when I think of Anderson, I think also of a relatively contemporaneous filmmaker whose body of work couldn’t be more different, and whose track record, once so promising, has been dire of late.

Kevin Smith came on the scene around the same time with his masterpiece Clerks, the “indie film par excellence” which set him for life in certain nerdy circles (like that of my friends when I was in middle and high school in the Nineties). Flash forward to this year, when his latest film Cop Out was from a screenplay not of Smith’s making and clearly a cash-grab; Smith has made more news lately due to his weight than his film work. In a lot of ways, Smith and Anderson reflect and contrast one another, not just in terms of their film styles (Smith, like Tarantino, loves the sound of his actors’ voices and most of his films are an excuse for characters to embark on pop-culture laden monologues in between set pieces with varying degrees of believability. Anderson crafts such a meticulous story with each film that his occasional verbosity in regards to dialogue can be forgiven most of the time). Anderson might be one Jersey Girl away from such a similar fate, but so far he’s managed to stay grounded in the quirky, winsome style that won him fans in the first place while also expanding the view finder on his storytelling lens to incorporate more than just a limited frame of reference.

They look thrilled to be in a Kevin Smith movie.

Pop culture junkies like myself are nothing without referential resources for our favorite objects of art, so I’d like to extend the Smith-Anderson comparison one more paragraph by comparing them to two other filmmakers of a contemporaneous time who were once collaborators. Smith is, to my mind, in the Jean-Luc Godard school of filmmaking, where the idea of a “story” from beginning to end is often ignored for the sake of characters spouting off intellectual ideas at one another to show their intelligence. It would surprise the hell out of me if Smith actually said that Godard was some sort of influence on him (he seems to cite the American independent cinema of the late Eighties, but that in turn had some influence from Godard at some juncture. Look at Spike Lee’s montage celebrating Rosie Perez’s various body parts in Do The Right Thing and compare it to Michel’s speech about loving the body parts of his femme fatale in Breathless and tell me that there’s no similarity there).

Anderson, by contrast, is more in the Francois Truffaut school, where characters are shaped by the story more than they shape it. They have a certain innocence about them, which is often shattered or at least bruised by the last frame. Truffaut’s debut feature The 400 Blows anticipates the changing view of children in cinema not as waiflike innocents of the Shirley Temple variety but as real, complicated individuals whose secondary status denotes a lack of comprehension from those above them in age (if not maturity). Antoine Doinel, who would subsequently be the focus of three more features and a short film, is Max Fischer’s patron saint, a poor student who’s more intelligent than he seems, but not in the ways that help him achieve the expected and desired results of his bourgeois surroundings. In the subsequent films, Antoine continues to follow his own path, much as the characters in each successive Anderson film pursue quixotic goals with little hope of success in the adult world that surrounds them.

While there is no overlap from one film to another (no recurring characters), Anderson’s films do suggest a shared point of view: the adult world of responsibility is scary and mean, but the childlike world we’d like to return to is forever beyond our grasp. It’s in the way that each character deals with this weighty issue that demarcates them from the protagonist of the previous or successive film.

Why did I refer to Anderson’s films as “childish,” then, if I seem to appreciate and even love some of them? The description is not meant to be insulting, or even pandering to those who would argue that Anderson’s body of work is little more than piffle. There are deep and disturbing issues that have to be confronted in each work, issues that his characters are ill-prepared to deal with in the “normal,” socially acceptable way. The trio in Bottle Rocket try to pursue a criminal career but louse it up, Max Fischer tries to blackmail his much older teacher into loving him, Royal Tenenbaum lies his way back into his family’s life when his hotel kicks him out, Steve Zizzou pursues an elusive creature that ate his best friend and gets his son killed in the process, the brothers in The Darjeeling Limited try to repair a childhood’s worth of damage done by their father, and Mr. Fox finds the lure of living above ground (and stealing from his neighbors) too alluring to resist. Each loses something of himself in the process, but also gains an appreciation of what it is that they learned in the process. In that sense, each film is childlike, because what is childhood but a continuing series of experiences which shape us into the adults that we become? It’s also transitory, however; none of Anderson’s main characters can shake off the clutching hand of mortality and return to that idyll of their youth.

“Glory fades,” Max says when he introduces himself to Rosemary in Rushmore, and from “Ozymandias” on down we’re reminded in pop culture that life isn’t permanent, it comes in stages that begin and end, sometimes with those of us it touches right back where we started. There is always the lingering threat of destruction, whether by your own hand or by another’s, in the films of Wes Anderson. In many ways, that destruction can come through childish behavior, as evidenced by the number of traumatic injuries brought about by reckless activity. Owen Wilson crashes his car into the Tennenbaum’s brownstone and runs over the beloved family dog; Max tries to kiss Rosemary and gets reminded in no uncertain terms that he doesn’t know the first thing about sex; and Mr. Fox gets his tail shot off after the owners of the factories he steals from pick up his trail. It would be nice to think that childhood is a time of innocence, and to some degree that’s true. But in order to mature, to become a functioning and contributing member of the greater society of adults, one must lose that innocence, whether by a single traumatic event or over time in gradual increments until one is hardened and “grows up.” That’s why I’d be comfortable with adolescents who are mature enough to handle some of the humor or thematic elements of the films (and believe me, there are sensitive teens out there; for every Miley Cyrus fan there’s ten or twenty potential Max Fischers) seeing the films, because they impart a message of sorts about life.

Much like Truffaut before him, Anderson doesn’t sugarcoat childhood: shit happens, and it often adversely affects those who are not yet of age to deal with it. Antoine catches his mother in the midst of an affair while he spends a joyful day skipping school; she later enlists him to keep their secrets from her distracted husband (his comical step-father). His children in the films aren’t cute but bratty, a precedent he set with his very first released short film, Les Mistons (1957); the children in that film hound a pair of young lovers with a mixture of mischief and jealousy over the budding sexuality that they cannot comprehend. Similarly, Anderson’s kids in films like Rushmore and Royal Tennenbaums aren’t babes in the woods; the arrested development of Royal’s kids ensures that they cannot function in the real world, while the children at Max’s private school pretend to be more world-weary and knowledable than they are (their knowledge coming from pop culture, as evidenced by Max’s continued staging of plays based on movies he’s seen). Disney’s wide-eyed adorables have no place in the cynical world of Anderson, unless they’re of the more recent “hip” type (and even that can be seen as more of a crass appeal to a changing commercial demographic than an understanding that kids are much more complicated than in Uncle Walt’s day). Childhood is a test, which is sometimes failed but never forgotten by those affected by it in Anderson’s world. The constant theme of retreat from the real world is a childish instinct, but one that every adult who’s ever wondered when the fun times stopped can relate to.

Having seen now every film that Anderson has directed thus far, I can safely call myself a fan of his unique and quirky vision. He’s not Tarantino, though that can be a good thing (the public acclaim that greeted Quentin upon Pulp Fiction might be damaging to a less media-savvy personality like Anderson). He’s not Kevin Smith, whose career started with a bright burst of profane creativity before collapsing in on itself and subsisting on commercial fare (though I hope he does find his muse again and return to some level of acclaim and artistic achievement). He’s not Judd Apatow, who has managed to marry the profanity of Smith with the sensitivity of Anderson and manage to make (for the most part) box-office gold. He’s not even Truffaut, whose films, while initially daring, did become more conventional following the failure of his New Wave-heavy Shoot the Piano Player. Wes Anderson is simply the master at doing what Wes Anderson does best, which is making children and the childlike view of life more appealing by deconstructing it and highlighting its flaws. In that sense, his films are “childish,” like a spoiled brat taking apart his toys to find out how they work and destroying them in the process.

In Wes Anderson’s world, you can put the toy back together, but it never works quite the same way again. And maybe that’s a good thing, because it opens the door to an adulthood outside the boundaries of what everyone else thinks is normal.

(Are you a child who never grew up? Or would you prefer a more mature Wes Anderson? Sound off in the comments)

Beautiful post. I’m a big fan of Anderson’s and I think you really nailed the secret to the appeal of his films. He makes these meticulous, dollhouse worlds where everything is just so, and then proceeds tear apart his characters until their emotional problems are splattered across their perfect world.

I’m in the same boat. I’ve seen all his movies and The Life Aquatic is, I think, a hugely under-rated movie.

Uh, anyway, great article! I think that Wes Anderson needs to do something different, but that thing is certainly not get older and more mature. That’s what Noah Baumbauch films are for…