Netflix’s House of Cards boasts an extensive cast, but it follows the rise and fall of two men in particular: Francis Underwood and Peter Russo. Underwood is the majority whip of the House of Representatives; Russo, a representative from Pennsylvania. Russo seems fairly satisfied with the modest power he has: an attractive aide he can sleep with, the ability to do favors for his constituency, a big office. Underwood craves power at all times.

That in itself isn’t too noteworthy. What makes it interesting is how much of the show dwells not just on power but powerlessness.

When Russo is plucked from obscurity to spearhead an environmental bill, one of the conditions Underwood imposes is that Russo get clean. No more drugs, no more drinking. To keep Russo on the right path, he sends Russo to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings with his enforcer Stamper. The congressman from Pennsylvania sits in a church basement every morning, drinking stale coffee and listening to other people’s stories.

20th century pop culture has given all of us, on the wagon or off, a passing familiarity with the twelve-step program that defines Alcoholics Anonymous. The first step, as originally authored in 1935: We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable. Is this something Russo does? Is this something anyone in House of Cards can do?

Say what?

Consider the first episode, where Underwood learns that he’s been passed over for Secretary of State, possibly the most important office in Washington outside of the Presidency. He spends the entire day in a despondent sulk, ignoring texts from his wife. When she asks him why he trusted Chief of Staff Linda Vazquez’s promises, he pouts, “I didn’t; I don’t; I don’t trust anybody.” He throws a temper tantrum, spends the whole night brooding, then comes up with a plan – a plan that will result in the sidelining of a senior member of Congress, the ouster of the Vice President, and one man’s death.

Is this a rational response to Underwood’s setback? Disappointment at a broken promise, anger at having one’s efforts go unrewarded: these are believable. But the steps Underwood takes not only put his entire career at risk – he stakes his own reputation on the education bill that he spends several weeks sabotaging – they put the relative strength of his party at risk as well. Think how it would look if Joe Biden resigned the office of the Vice President in 2010 to go campaigning for his old seat in Delaware.

Underwood considers these stakes acceptable for the game he’s playing. This, frankly, is not a man who can admit powerlessness.

Russo has a hard time admitting powerlessness as well. This stubbornness reflects in how little he participates in the AA meetings that Stamper drags him to. “He never shares anything,” Stamper says. While there’s no requirement that you share something at an AA meeting to earn your place, openness about your inability to deal with your addiction alone is an essential step.

But Russo doesn’t clean up because he wants to repair his life. He cleans up because he wants to earn Underwood’s trust and become governor of Pennsylvania. Getting sober is a means to an end. He’s using that motivation – the chance for political glory – as a lever to help him stay on the wagon. But when that carrot is taken away, in a deliberate ploy by Stamper and Underwood, he has nothing left to stay sober for.

Not exactly a power move.

To live and work in Washington means to seek after power or serve those who do. It’s a city that produces no exports but law, fulfills no need but legislation. You’re there because you want to sway human affairs. The thing I found hardest to believe about House of Cards is that the Washington it depicts has any AA chapters at all. Can you imagine a sitting member of Congress running the risk of being photographed outside a church basement? Can you imagine a member of the Ways and Means committee seeking to make amends to those he had harmed?

(In real life, there are doubtless actual support groups in DC that operate with healthy discretion. But this is the DC of House of Cards, where people are more rabid and cruel than in the world we recognize)

So Russo cannot own up to his powerlessness and, as such, his powerlessness overtakes him again. Underwood can’t admit to his powerlessness either, but he appears to end S1 on an upswing. His schemes have triumphed and he’s about to be selected to replace the resigning Vice President. But is he in control, or is he just bouncing between relapses?

Is there a moral … something … that should tell me what to do here?

Russo’s addiction is alcohol (or some blend of booze and cocaine). Underwood’s addiction, on the other hand, is obedience. He gets off on having people do what he wants. Sometimes this is a subtle high, as when he arranges circumstances such that he gets control of the President’s education bill. Other times it’s an uncut dose, as when he takes Zoe roughly in her tiny apartment. Either way, Underwood can’t stand when people don’t dance to his tune.

Put that way, it sounds petulant rather than noble, just as the boasts of a three-day drunk sound. And just like a career alcoholic, Underwood is heedless of the damage his addiction does to those around him. His need to whip Claire into line costs him the environmental bill that would have put Russo on the governor’s ballot. It also drives her into the arms of her old flame, sexy Manhattan photographer Adam Galloway. When she comes back, there’s no tearful reconciliation, no promise to change his ways – just back to business as usual. We might call Claire an enabler if she weren’t co-dependent on Underwood’s style.

S1 of House of Cards is the story of two addicts on alternate trajectories. Both have coping mechanisms that they’ve built up over years of practice. Both see those coping mechanisms fail, with damaging results. But Underwood lives in a city that caters to his addiction and punishes Russo’s. He has his network – Claire, Stamper, Congress, the Oval Office – to prop him up when he falls. Russo has nothing, and the few people he has, he drives away. The result for him is tragic. Will the result for Underwood, in later seasons, be the same?

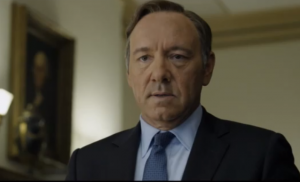

(As a postscript, it’s ironic that this is one of the first TV series released in its entirety on its debut weekend. Seth Godin called this a mistake, but Kevin Spacey, at least, seemed to understand the reasoning behind it. “When I ask my friends what they did with their weekend, they say, ‘Oh, I stayed in and watched three seasons of Breaking Bad’ or it’s two seasons of Game of Thrones. For whatever reason, people are consuming large chunks of story – they’re getting really involved in big arcs.”

So, yes, it’s a show about addiction that’s catering to TV addicts.)

The most disconcerting aspect of the completely on-demand model for releasing a series is that it eliminates all established unwritten rules on spoiler warnings. I’ve only watched six episodes of the series and this article is fairly spoiler free to me, but I still read it with some trepidation.

What is the etiquette for something that can be binge watched?

I’ll echo that. But that’s part of the larger problem, which is that without an air date there is no natural point in time around which people interested in the show can meet anywhere and talk about what’s happened.

As arbitrary as releasing them that way would be, it’s really the equivalent of a show tossing a hash tag up on screen. It’s not like people need that to tweet about the show (usually the hash tag is something you could’ve guessed, anyway), it’s just that it helps consolidate that interest a little more efficiently.

Of course, there’s another way of looking at this, which is that this uncertainty makes people want to finish HOUSE OF CARDS quicker. I always want to watch something sooner if I’m concerned about spoilers.

I guess you could treat a show like this the same way people treat novels in book clubs – sure, the whole novel was published years (maybe decades or centuries) ago, but we’re only going to read up to chapter 13 this week, and we won’t discuss anything after chapter 13, then next week will be up to chapter 15, etc.

Maybe the key is to find a group of like-minded friends who want to watch it, and set a schedule together.

I started watching today, and am up to episode 7. TV addiction indeed.

Heh, yeah, like Perich pointed out, a show about addiction is kind of addicting. The binging in the show is a nice meta comparison to the binging the show itself is conducive to.

Of course, whenever I’ve consumed all of a piece of media in its entirety, it’s nigh impossible for me to leave out what’s “supposed” to be left out of the conversation if discussing only part of it. I know some people are better at this than others, but I’m kind of terrible. Even if I don’t specifically mention things, they influence my analysis or whatever. Alas.

Speaking of book clubs, this series is based off of a British one, which is based off of a book.

John, how can there being AA in D.C. in House of Cards surprise you? I think Russo going to an AA meeting in a church basement makes great sense- rather than sending him to one of those fancy rehabilitation centers, they send him to a regular AA meeting with “commoners.” Recall, the cleaning up thing was all part of Russo’s contrived story, so they wanted people to know he was clean and doing things like AA, and he’d get more of the “everyman struggling with addiction” cred if he went to meetings with regular citizens instead of taking time off to “recover” in a fancy resort-type facility. And he probably wouldn’t have had the time to go away for recovery, anyway, given how they only had a few months to get the various bills through and such. Plus, given the high poverty and crime rates in D.C., finding an obscure but still entirely open (in the sense of who’s allowed to attend) AA group there would probably be immensely easy*. So Russo going to a regular AA meeting is perfect for Underwood’s goals.

I agree Russo has trouble entirely admitting his powerlessness with his addictions, though. I do think he realizes there’s a problem, but he can’t seem to go so far as to owning it enough to take control. He’s shown struggling with it constantly, such as the scene where he dumps the packet of cocaine down his bathroom sink.

I think the show says a lot about addiction in very reall ways. One of the most strenuous things for persons and families of persons addicted to alcohol, drugs, etc., to deal with is that the person with the addiction has to choose to give up whatever it is on their own terms. It can’t come from someone or somewhere else. Sure, there are the stories of people that nearly die and come around, but the experience of near death scares them into desiring change on their own. One of the big reasons “interventions” often don’t work is because the person being approached feels affronted and, even if they agree to try quitting, they’re doing it more as if they’re under duress and have no choice. Choosing has a lot to do with it, because that, again, is about power; for a lot of people, they feel powerless in so many other areas of their lives, “choosing to drink” is one of the few things over which they convince themselves they have any power at all. So they have to choose to exert that power by not drinking (or whatever) themselves. So Russo can never entirely commit to dropping his addiction, in part, because going clean was pushed onto him, highlighting another aspect of the powerlessness involved in addiction. Having someone else choose for him that he needed to quit was a barrier between full recovery and backtracking.

One final note, I think Claire has the same addiction as her husband, too, except she isn’t as skilled at reigning in people to feed that addiction. She certainly seems to enjoy exerting authority and control over others, but other than when she strong-arms her former partner and fires her and a bunch of other people, it doesn’t really seem to work out in her favor too much.

*And no, I’m not saying all low-income persons are drinkers- but there is definitely a high correlation between poverty and alcoholism, although the direction is impossible to determine.

Very early in The West Wing it is established that Leo McGarry is a recovering alcoholic and goes to AA meetings held with the White House.

I love House of Cards, and the author makes some interesting points here, but every word he writes about Washington, DC–a city where, in fact, the majority of citizens live and work outside of the corridors of power of the U.S. government–is willfully ignorant, proudly dismissive, and unfailingly moronic.

Hey Wrather, remind me how to update my “About” tagline again? I’ve got a new pull quote.

I saw “John” and just assumed you were sock-puppeting.

My guess/feeling is, that if House of Cards is a big enough success, they will make more than two seasons. So it got to end with him either becoming president or fall just before. Maybe he will fall like Nixon, being exposed as a (yes) crook after becoming president.

It is difficult to guess the outcome, because the series is so cynical, so maybe his wicked way will triumph in the end…but my guess is that, as the title suggest, he will build a bigger and bigger house of lies(/cards) until it all comes tumbling down.