Many rock purists and music snobs (myself included) often lament the quality of most modern pop/rock music. “Music these days is so trite and derivative,” they say. “It’s just been downhill since the 60’s and 70’s. Those were the days.”

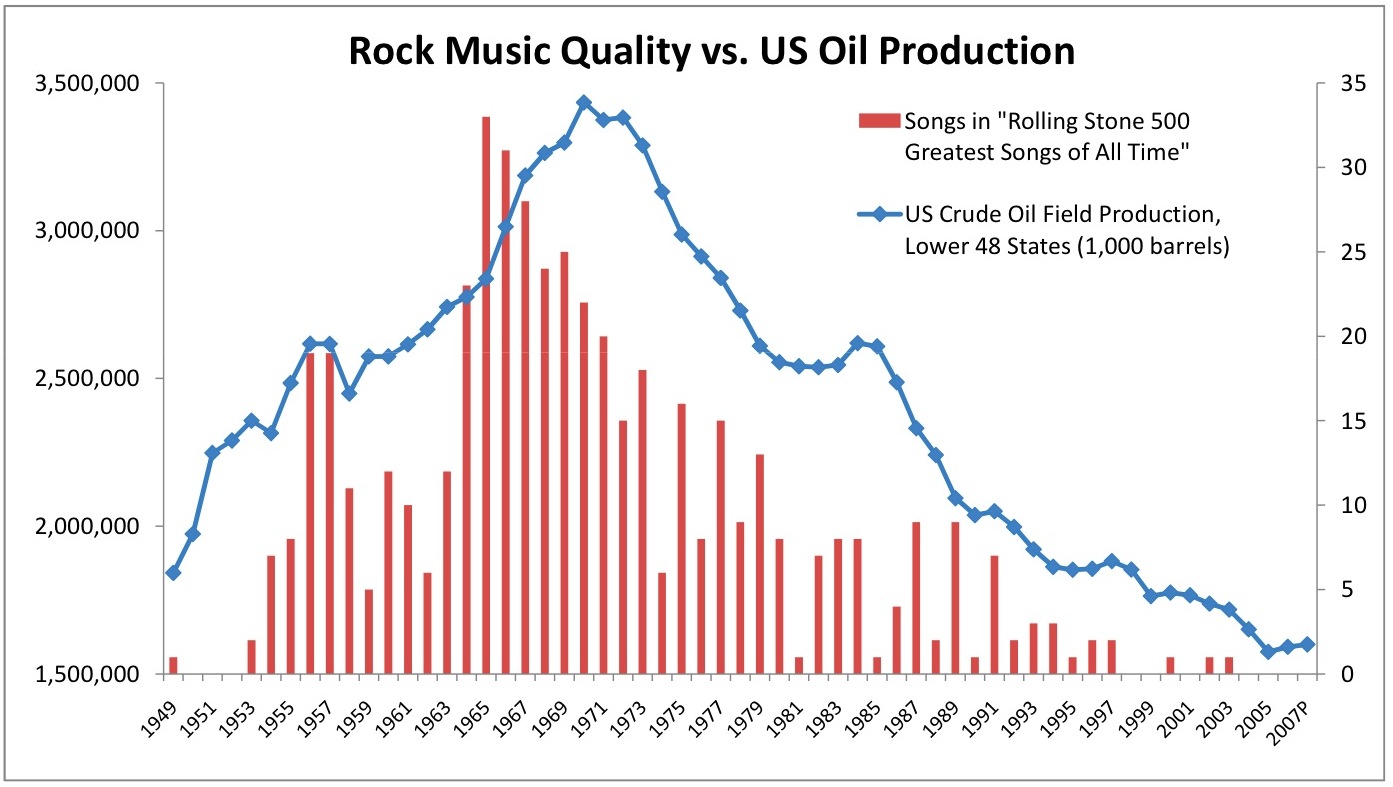

A few years ago, Rolling Stone magazine added fuel to the music snobbery fire with its “500 Greatest Songs of All Time” list. Anyone casually paging through the list would notice that the bulk of the list was comprised of songs from the 60’s and 70’s, just like the music snobs always say.

I, however, wasn’t content with the casual analysis. So I punched the list into Excel, crunched some numbers, and found an interesting parallel between the decline of rock music quality and, of all things, the decline in US oil discovery and production:

(Sources: Rolling Stone Magazine, US Department of Energy)

Analysis after the jump. Drill Baby Drill!

First, a little theory. The decline in U.S. oil production* is explained by the Hubbert Peak Theory, which states that “the amount of oil under the ground in any region is finite, therefore the rate of discovery which initially increases quickly must reach a maximum and decline.” Makes sense, right? The same theory can apply to anything of a finite quantity that is discovered and quickly exploited with maximum effort.

First, a little theory. The decline in U.S. oil production* is explained by the Hubbert Peak Theory, which states that “the amount of oil under the ground in any region is finite, therefore the rate of discovery which initially increases quickly must reach a maximum and decline.” Makes sense, right? The same theory can apply to anything of a finite quantity that is discovered and quickly exploited with maximum effort.

Including, it would seem, rock & roll. I know, the RS 500 list is not without its faults, but it does allow for some attempt at quantifying a highly subjective and controversial topic and for plotting the number of “greatest songs” over time. Notice that after the birth of rock & roll in the 1950’s, the production of “great songs” peaked in the 60’s, remained strong in the 70’s, but drastically fell in the subsequent decades. It would seem that, like oil, the supply of great musical ideas is finite. By the end of the 70’s, The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, the Motown greats, and other genre innovators quickly extracted the best their respective genres** had to offer, leaving little supply for future musicians.

The counterargument to all of this, of course, is that the RS 500 skews unfairly towards the earliest, most groundbreaking works of music and unfairly penalizes later creations for simply coming after other works. For example, why was Green Day shut out of the list? I could point to dozens of songs on the RS 500 that are inferior to some of the classic tracks off of Dookie, almost all of which came from the 60’s and 70’s. But even if you assume that the RS 500 functions more of an indicator of musical early-ness, the Hubbert Peak Theory still holds true. A whole host of talented musicians set out exploring the vast uncharted territory of modern pop/rock music that was first made possible by the electric guitar and the standardization of the rhythm section. The resulting works from this period (the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s) will forever stand out by virtue of their originality. Popular music** may never again see a period of innovation at a magnitude of its first explosion.

I don’t think I’m being pessimistic about the outlook on pop/rock music or snobbish about my retro music tastes. I think the same idea applies to other creative fields that follow a similar arc of rapid exploration followed by derivative works. Assuming some constraints on the definition of the form, the amount of innovation that can be done within that form is finite. Most of it will come early and fast, then decline after the peak. Impressionist paintings. Star Wars movies. I could go on.

Now, if only we could drill for some new reserves of pop music innovation. Perhaps there’s a new Motown hit machine waiting somewhere in the Gulf of Mexico, waiting to be unleashed. Let’s get drilling.

I know there’s plenty of room for arguing my points, so please sound off in the comments.

*I left off Alaska from the data set mostly to make the graphs line up better, but also because the “fixed supply” concepts holds better if you look solely at the lower 48 states and not the one with all the oil and all the hockey moms.

**Although the RS 500 list includes a smattering of rap/hip-hop, it’s so deficient in that regard that i’m excluding that genre from this analysis. I wonder, though, if a similar analysis could be conducted around that genre that shows the discovery/innovation explosion after hip hop’s genesis in the late 1970’s.

Now wait a minute, here. While I agree, a lot of modern music is terrible, I think it does a disservice to the modern music scene in general to assume it’s overall worse than previous decades. Rock ‘n’ roll, when first started, was decried by many, many an “adult” at the time; and the people defending it against those arguments bred the ones that wrote the article, training them to think as they do/did. Who’s to say that modern pop music isn’t in the same boat? I see the argument as alluding to the sort of curmudgeony, “Kids these days have no taste,” sort of attitude every generation faces by its predecessors. The teenagers (and probably a lot of people around our age, the 19-30 range) that do listen to pop and love it would probably be very angry that some of their favorite bands were excluded from that list. I haven’t seen it yet, but I can think of numerous groups with amazing songs that were most likely not present.

It may help to know the criteria they had for putting songs on there. Did it have to sell a certain number of copies? Did it have to even be on the radio? That’s another problem: there are countless songs out there that are good, better, best, that weren’t released as singles. So that’s kind of like the “if a tree falls in the wilderness, does it make a sound” argument: do songs like that “count” or not?

Yes, I’m a “classic” fan, too. The Mighty Zepp, the Stones, Cat Stevensen, oh yes. But music itself has evolved into something different, so comparing The Who to Lifehouse is like comparing kiwis and mangos- both are classified in one large and overly broad category for convenience sake when putting them on the shelf, but they are clearly related only distantly.

This is incredibly interesting, and I have to say that the RS500/Crude Oil plot sucked me in.

However, in addition to the questions that Gab articulated nicely, I have one problem with this theory: the top 500 songs of all time, even from a single source such as RS, is necessarily going to change along with changes in personnel and perspective over time. There are reasons why the local classic rock station’s July 4th countdown of the 100 greatest rock songs of all time changes a bit every year. As I have heard Sheely say, “that shit covaries with a lot of other shit.” Crude oil production – that’s hard data.

We might not see the same correlation if RS were to reconsider their top 500 in, say, 10 years. That said, your theory probably isn’t far off in that only a handful of the classics might be supplanted while a greater proportion of songs post-1980 might be replaced by more songs post-2000 that might have had enough time to make their own gravy.

Oh, and I really hope that by linking to “Impression, Sunrise” you weren’t declaring that the peak of Impressionist painting.

Fascinating post.

I’m going to now show my true colors as that annoying indie girl, but there is a lot of innovation going on in popular music these days. It’s just not going on on the radio. This has more to do with changes in the music industry than changes in the quality of musicians. Back in the 1960s, there were big record labels, of course, and some did make “boy bands” from scratch (see: Motown), but, for the most part, musicians perfected their craft and then were discovered.

Somewhere along the line, by the 80s, the music industry consolidated so there were only really five or so big labels. I’d assume that was detrimental to new artists. Of course, that’s not to say that good rock music didn’t come out of the 80s and 90s– somehow we did manage to get Nirvana, after all– but listen to your crappy “80s, 90s, and today” radio station to hear all the rest of the junk.

Now, of course, music on the radio generally is manufactured, mostly by the Disney company and similar conglomerates. While “I Wanna Be Like You” from The Jungle Book was an excellent song, I think we can all agree that Disney might not know too much about what great rock music sounds like. Anyway, all they care about is the bottom line. With the advent of the Internet, smaller labels can make enough money to survive through that “long-tail” theory, so there is some excellent indie music happening.

A question that arises is, “Is the innovation happening in the indie scene as good and interesting as the innovations that happened in the classic rock era?” It’s possible that people might think that these indie innovations are either A) too “out there” or B) decent, but not as good or revolutionary as those by Hendrix or the Beatles. That might just be a bias, though.

As much as I love indie stuff, I have to admit that most of them don’t rock very hard.

As for the peak rock theory, I recently read on a blog somewhere (can’t find it, sadly) that had the same premise, but then the writer realized that if you took the same three or four notes and tried to write a new song, you’d come up with thousands and thousands of ways to write the song. Of course, not all of them would be good, but I assume at least some of them would be…

That was my Music Comment. Here’s my Other Medium Comment.

I was very interested in your notion of innovation as an indicator of greatness. I’ve had this argument several times. There are indeed people who think that a piece of art cannot be considered great or even good if it does not innovate in some way. Thus someone who perfects an already extant form is inherently less talented than someone who starts from scratch (inasmuch as any artist can start from scratch).

But I think this is a huge problem for artists, particularly writers. The postmodern movement (if you can call it that) opened the door, allowing any piece of crap to be considered high art. I’m not knocking postmodernism, mind you. I’m very fond of it, actually. But it was the “anything and everything” movement. All the rules were finally broken.

But once postmodernism happens in art, where do you go next? Harold Bloom claims (not that I listen to him all the time) that new artistic movements arise when artists reinterpret (or misinterpret) what came before and consciously break from that tradition. How can you break from postmodernism, with its “anything goes” attitude? You can go back to naturalistic realism, but that’s nothing new. Call the 1800s and see.

How do you break the rules of a genre that had no (or few) rules to break? What we seem to have in the world of writing these days is a lot of (I think) silly attempts to be “innovative” and “postmodern” (think of those youngish writers — not going to name names — who use different fonts in their novels, and the literary world swoons over them. OMG how clever! They use different typefaces! They leave blank pages in their books to express the nothingness of their lives! Feh). The other route for the “literary” writer, interestingly, is to borrow from genre fiction (genre tropes are “new” in the literary world, anyway) but then adamantly deny that your work has anything to do with genre fiction (ew, genre fiction doesn’t sell!). So you have people saying The Road and The Time Traveler’s Wife are so clever and “new” (never mind all those sci-fi authors writing about the apocalypse and time traveling in the 1950s) while denying that they are in any way science fiction. Perhaps we should call this “the Kurt Vonnegut approach.”

In other words, in order to succeed in the “literary” genre — an indeed it is a genre: you have to look for specific types of agents and publishing houses if your work is “literary,” whatever that means — you need to resort to cheap gimmicks. Even if you wrote the best Romantic novel today, it would not make money or maybe even be published, because Romanticism is so over. It’s not innovative anymore.

It’s a conundrum. In order to make it as a high literary writer, you can’t write in certain genres, but there is no “post-postmodern” genre to write in, either, so everyone’s just trying to latch onto po-mo and keep doing that old stuff because it looks new, even when it isn’t any longer. I’m not in the mood to make an Excel file of the best books of all the last century, but I bet the graph drops off precipitously after the 1960s, just like your graph up there. Whether that’s because of the corporatization of the publishing industry or because of silly ideas of what good, innovative fiction looks like, I don’t know. Same goes for the visual arts.

Re: Indie music.

I’d love to see some Venn diagrams showing a) how much of it is truly innovative in terms of formulation/execution/production and b) how much of it is good in terms of that je ne sais qu-ality… and then percentages of those groups that people think will stand the test of time. My guess is that, 20 years down the line, a) will be very little, b) may be a little more, and the intersection of a) and b) will be incredibly small.

One problem that indie music has going for it is the blogosphere, wherein most are too focused with finding the Next Great Thing before the other guy so much that many an artist has had an over-enthusiastic blue ribbon pinned upon their chests…

I’ve been reading for a good while now that I’m *really really* supposed to love the Arcade Fire, but I just can’t muster up the excitement. I hear this happens to lots of guys — should I go see a doctor? The sad part is that the music blog cycle is all of about 3 minutes, so I have no idea if I’m still supposed to like the Arcade Fire or any other band du jour.

How much of the perceived greatness of a band is due to blogger hype, and what’s the half-life of said hype? When it wears off, maybe we can see what sticks.

What bothers me about this conversation is that there is an undertone of what is or is not “good” in terms of art. But art is completely subjective. No two people will agree 100% of the time on what is or is not “good.” That’s why cushman is so right about how the list would change. It depends completely on the people making it. All art is like that, be it music, literature, sculpture, paintings- anything that has the potential to be interpreted is thus defined subjectively by those interpreting it. EX: I don’t think modern art is “good” at all. A blank canvas with a single dot in the corner isn’t even art in my opinion, but there are those out there that believe this is amazing and beautiful, and they’d pay millions of € to have it on their wall.

So my point is that we could argue about what’s good and what isn’t good all we want, but we’ll never come up with a definitive answer or guidelines because we each have our own internal ideas about quality and worth and beauty and all that kinda jazz. And even if some rules are set up, we will each have exceptions to them or disagree as to whether different examples of art fit these rules or not.

Oh, and mlwaski, I agree, there are a lot of indie groups out there making wonderful music that doesn’t get on the radio. I was hinting at that before, but didn’t really go into it too much. I love sharing y music with friends that haven’t heard it before, though. I get a lot of, “Why didn’t I know about ___ before?!” My two favorite songs at the moment are by artists nobody else has heard of whenever I mention them.

I think it’s true that the rock/pop oil field has been virtually dry for many years now, but I think something has been overlooked. It is not the only oil field.

Before rock/pop, there was the jazz oil field. In the 70s/80s the rap oil field was discovered. It too was rapidly explored, producing a geyser of creativity. Just like rock, after a decade it had more or less dried up and we are now left with tired, derivative rubbish.

Come the 90’s we find the dance-music oil field, with exactly the same results. Early 90’s: amazing. Now: rubbish.

Rock music is, by its nature, limited. There’s only so much you can do with an electric guitar, and most of it has been done. We’re left with an army of die-hards trying to suck the last dribbles of black gold from a largely dusty hole.

If people start innovating too much, then the music is no longer considered rock. A new rock/pop oil field would never be accepted, especially not by the people who maintain that all the best songs were written in the 60’s.

Much as it sucks, we have no choice but to sit and endure this period of mediocrity until musical oil is struck once again.

Wait, are you people implying that the Jonas Brothers *aren’t* innovators?!

Gab: the RS 500 list was “based on votes by 172 musicians, critics, and industry figures” (according to the always reliable Wikipedia). Definitely highly subjective.

Cushman: the Monet was just a random impressionist work that I found on Wikipedia. Empire Strikes Back, however, is a simple example of how peak theory applies outside of oil and music: after the initial innovation/discovery of the franchise, it quickly reached its peak, then suffered a long decline after all the originality had run out.

Cushman: I think you’re not supposed to like the Arcade Fire anymore, since they sold out or something. I personally say, “Their first album was better.”

As for the “is indie music actually good?” question, partially Gab is right and good is subjective. I’d also argue that the songs and bands we consider great are those that have influenced those that came after them. The Beatles aren’t only great because they made catchy music; they’re great because everyone after them built on what they made.

If we use that definition of greatness, then I’d bet you’d be right, and indie music of today will not be considered great in the future simply because those bands and songs failed to influence future artists to the same degree. Why not? Less exposure.

And I guess the fact that us faux-hipsters turn our backs on bands at the drop of a hat doesn’t help much, either. But, then again, in twenty to thirty years this indie stuff will be nostalgic and therefore good again…

Oh, Oh, I wanna jump in too!

Alec Harkness mentioned jazz, but only in passing. I think that deserves a much broader look.

On the one hand, we can look at jazz and say it’s a counterexample. Here’s a field where innovation continued for sixty or so years, with new styles constantly evolving. Louis Armstrong was influential, but so were Coleman Hawkins, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Wayne Shorter. (To bonk through the decades) The innovation doesn’t appear to fade out.

Except then it did. Nothing really new has been done in jazz since the 1970s. There are still a number of amazing players, and it’s still being performed, but after fusion (and if you insist, but then I shall have to kill you, smooth jazz), there’s nothing really new.

There are those that argue that this is single handedly Winton Marsalis’ fault, but this seems a bit hysterical. Even if it is, however, can anything be done?

The other question this raises is; are these subgenres really all the same thing? Was Satchmo drilling the same hole as Trane? Coming back to rock, is it really fair to even plot the Beatles and Nirvana on the same graph?

And what are the long term implications? Can music be “saved?” Is there going to be a “next big thing?” Where do we go from here?

Discuss.

Just like oil, Rock and Roll is a commodity with a highly inelastic demand curve. While less and less crude Rock and Roll is being discovered, our thirst for Rock and Roll remains insatiable:

(if that link didn’t work, check this video:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DWLpbcgc814 )

…And just as for oil, men will deploy a whole Army to ensure their access to Rock and Roll.

I’m pretty sure this is the next big savior where we are going from here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nm3mMs33Npg

This shit is a fucking wind turbine with solar panels on the blades.

The scales are unequal. The oil graph is much flatter than the music graph when plotted on equal scales. Plot it on a log scale and you will see what I mean.

That’s an interesting graph! Are the years the same for both data sets or did you fit the Oil production set to the song set?

I agree with mlawski, the innovation isn’t happening on the radio or MTV. Genres are more spread out than just “Pop/Rock” now and so the innovation is taking place in several genres/subgenres. Sure, a lot of people don’t like metal music, but there is tons of innovation and lot’s of really great music being made in that genre (Between the Buried and Me, The Human Abstract). There’s lots of innovation in indie music, in hip-hop (again not the crunk B.S. that plays on radio and MTV). The real innovation is happening on Myspace, Torrent websites, and music blogs – not the radio.

Releasing singles and getting on the radio are not the same thing Gab. You say “the mighty Zepp. Does it surprise that Led Zep only released one single?

1. The graph shows a spurious correlation. This reminds me of the study that looked at loads of variables to predict the S&P 500 and found that the price of butter was the best predictor. This is a classic example of the data mining problem. As Ronald Coase said, “If you torture the data long enough, Nature will confess.”

2. If you don’t think the correlation is spurious, why does rock lead oil production?

3. Why did rock peak in the 1960s. One can argue that this was the heyday of rock. The peak year is 1965. I suspect that the Beatles had something to do with it. There is also retrospective bias: it takes time for a song to become a classic. Therefore, we would expect the number of classics to decline over time after an initial peak.

4. The time series has two peaks: 1956-57 and 1965. I’ve explained 1965 as due to the Beatles. Probably other factors were involved. The earlier peak reflects the height of rock-and-roll. Rock-and-roll was actually dying before the Beatles appeared.

5. Can you email me the spreadsheet so I can have a go at the data? My only journal publication to date is statistical.

Jesse: Well, that only makes it more convoluted, doesn’t it? I mean, Zeppelin gets played all the time on the radio, so why is that the case if they only released one single? And why, then, do so many bands remain in obscurity when they have more talent in the toe of their managers than the entire machine behind some of the stuff that goes platinum? If Zeppelin songs that weren’t officially released as singles made it onto the list, why can’t stuff by people nobody has heard of?

In general, lists like that, the “Top Whatever”-s of the world, always unnerve me because, no matter what is being listed, there are always, always going to be disagreements as to what is on and where it is.

(1)

You seem to be missing something : unlike oil or other resources which on any human scale are effectively “finite” and non-renewing, human CREATIVITY and IMAGINATION would seem to be renewing at an individual and group level. At the macro level, I agree, there seem to be particular periods of unusually high quality artistic output (not just in music) – and others perhaps of unusually low quality output – there have been Renaissance periods surrounding e.g. the close of the Roman Republic and the early Empire; Charlemagne and King Alfred’s courts; and of course the “Renaissance” proper. But surely each generation of homo sapiens is, to continue your metaphor with greater accuracy, not like oil, an effectively finite resource formed by restricted conditions over thousands upon thousands of years, but like a forest of individuals with varying heights and depths of creative quality – a resource potentially visibly RENEWING over the space of a lifetime – if not sometimes over smaller timescales. At the individual level, the single human being can go through peaks and troughs of inspiration and creative output over relatively short spans of time throughout their life, as their brain mulls o’er the raw input of experience and artistic application etc. Your data might be correct but I suspect something is lacking in your model / analysis – all things being equal, IF human creative output IS a short-span renewing resource, one shouldn’t expect this sort of data – there must be more factors at play, or something else missing – any ideas from people familiar with reliable research in this area???

(2)

…Also, I’d be interested to see what would happen if you drew up similar graphs extended beyond the unparalleled democritisation of media etc., partly as a result of unprecedented development in science/technology and hence e.g. population in the 19th and 20th Centuries on…it’d be difficult to draw up an objective criteria for aesthetic quality over a wider timeframe, but doing so might reveal more powerful (i.e. more general) patterns of explosive exploitation -> arid or derivative formalism etc. within discrete genres or media of art throughout human history…

(3)

Paradoxically, I’d suggest the SIZE of the explosion of rock per se was dependent in part on so-far unique historical conditions – unprecedented science/technology -> unprecedented access to the means-to-make-and-distribute-mass-media (gosh, a German compound word’d be handy here) + an unprecedented mass audience with the demand and capital to exchange for mass media (let’s not forget the rise of rock in part coincides with the rise of what the ad / marketing industry dubbed “teenagers” – a new mass market of young people with more disposable income than before in the new post-WW II world, with all the spinoff benefits of technology developed in that conflice etc., and a demand perhaps in reaction to the conservativism of the War generation, for explosive socio-cultural freedoms – including in the area of sexual relations.) So the size of the spike on your graph – indeed, perhaps even the supposed pattern of marked distinction between the “crest” and “trough” may be unusual, and just temporary and specific results of local circumstances? What do others think?

I’m just going to focus on the alluded-to-class issue. The market for rock was, indeed, much larger because of the availability and access rock n roll had to a much greater amount of consumers. When Mozart and Beethoven were “popular,” only elites had access to their music. The poor masses had their own traditional forms of music, but look at how history has dubbed the expensive composers as the definitive music of their generations. Those elites wrote history, so their music was proclaimed more important, even though their existence depended on the people in the slums playing the fiddle. Then the industrial revolution took place, mass production became commonplace, and the rise of the middle class brought a whole new group of consumers and products into the market. As such, instead of only being played in parlors and concert halls like the music of the previous centuries, rock n roll was on radios and televisions. And even if they couldn’t afford one or the other, the middle class could at least listen/look at stores, and they probably knew somebody with one or the other device they could mooch off of, too. Even lower-class members of society had easier access to this music simply because it was “out there” in a way previous forms of music hadn’t been- more public, I guess you could say. And yes, advertising had a LOT to do with it. As has been said before, music became manufactured as well. A precise formula for what would or would not sell was concocted, and “talent” was made to fit that. Today, while the middle class may be suffering greatly, the dependency the elite class has on it operates in a fashion wherein what the middle class wants dominates society- the elites remain elite by selling the demanded goods, i.e. music, to the middle class. The bulk of the capital in society doesn’t come from yacht and country club membership sales, but from the sale of products consumed by the middle class. The weakness in this argument is, of course, that the elites can still mold it to what they desire. After all, Miley Cyrus goes platinum- WHY? Well, she has the power of a huge corporation behind her: Disney can advertise the fuck out of that little bitch and make people THINK they want her, when really, if they thought for themselves, they’d realize she’s trash. So maybe we need some sort of Myspace revolution against the corporate machines of the bourgeoisie. We can get the artists that aren’t getting promoted so much out there and have some REAL talent on the airwaves and on the sales charts.

In point 1 of my previous comment, I left out “in Bangladesh” as in the price of butter in Bangladesh was the best predictor of the S&P 500.

Now, everyone find something better to do than study spurious correlations. Pick up a good statistics text, for example.

Wow, I’ve been really impressed by the interest this post has generated. Thanks to everyone who’s commented!

If you’re interested in how I came up with this craziness in the first place, be sure to check out the latest podcast episode:

http://www.overthinkingit.com/2008/09/29/episode-13-crossing-sections-off-the-map/

And yes, I do realize this is a spurious correlation. And no, in no way was I implying causality.

For anyone interested in seeing the raw data and creating spurious correlations of your own: send me an email at lee (at) overthinkingit (dot) com and we’ll talk.

Forgive me if someone’s said this already, but US oil production and RS 500 proudction, correlate roughly not only with one another, but also with–and this is most important–the FUCKING BABY BOOM which was driven by postward economic expansion.

What we’re looking at here, really, are expressions of the growth of the US economy after Germany et al were knocked out of the picture. Economy gets bigger, music gets better, population grows. Whether better music in the 60s and 70s means the genres were exhausted in those years (a cool idea, but I’m not buying it), or whether the RS 500 simply reflects the musical tastes of the baby boomer establishment (far more probable), is something to argue about.

Disaster post: Typos everywhere, misplaced commas. That should be “postwar economic expansion”

i have to admit, i didn’t take the time to read all the comments. i am at work, and i do have to pretend somewhat that i’m typing up something very important.

so if i’m repeating anything that’s been discussed, sorry.

i think the general analogy to genres as oil fields that can be sucked dry is really missing the point, or one of the bigger points of the value of music. certainly, some value in music is to intrigue us, a la progressive technique – but two elements of modern music make that totally unnecessary to make something good, or even great.

first: music has the power to move without being different than things we’ve heard before (at least generally different – not the same notes w/ the same rhythm) – the abstract emotional power of beethoven’s seventh may have had progressive clout when first performed, but it doesn’t to listeners nowadays – it’s just gutwrenchingly powerful. there are musical formulas that have been proven to ‘work’ in affecting people, and recycling them doesn’t make them any less valuable – it still takes great craft to pull it off, in most cases.

second: words. lyrics. i happen to be a fan of folk music, but i recognize that powerful or interesting lyrics are the only reason folk survives. dylan wasn’t musically interesting, but people still listened. it translates, although maybe not in such a focused fashion, to other more ‘rockish’ music. it’s part of why i feel like radiohead has plateaued (recently slowed down progressive sense + can’t understand a damn word he says = i get bored w/anything after kid a), and why i can listen to soul coughing records that groove and groove again in much the same way.

so progress-ivity doesn’t make something great, and a lack of it doesn’t limit greatness. that being said, i am someone who prescribes to the notion that art should be an ever-expanding field, and that’s made possible by experimenting with new sounds and combinations. since i also think that art is essentially our way of very slowly realizing the aesthetic value of everything (all-inclusive), i try not to snobify and throw out the ‘old’ music that doesn’t intrigue our curious ear. artistic movements are moods of a specific subset of culture that get projected onto larger groups by institutions of art.

popular ‘rock’ will die and be reborn every so often, but good music never goes away. it just gets harder to find. i suppose one has to drill deeper.

and yes, to clarify, i did intentionally put dylan in the past-tense. i saw him a few years ago, and i think it’s offensive that anyone with integrity would tour in his condition (and make people pay to see it). if they had found a lung cancer/chronic bronchitis patient somewhere in hospice, painted on some child-molester facial hair, put a cowboy hat on him, and thrown him in front of a blues band, no one would know the difference.

Lee, this is a very cool concept. As someone who has had a handful of songs published in the past I would say it’s like minded management styles of both industries. The oil Companies don’t want you to have choices of what types of energy to use let along the manufacturing of plastics and other petroleum based products. The Recording industry doesn’t want you to have so much choice in new artists that they have to back the advertising campaigns of a bunch of different artists CD’s let alone the payola to get it played on radio.

It’s expensive and they just aren’t selling music anymore. They are selling fashion, jewelry and many other products along with the music these days. The male singer with the best abs to show off the new (insert clothing manufacture name here) or the female vocalist with the most junk in the trunk, you get the idea.

Good music is out there still, King’s X is a great example. The have been putting out Records / CD’s since 1990 but never peaked the industries pallet for radio play.

Dude! I totally dig this article. So much so, I’d like to put it in Vocals Magazine’s hard copy.

My thoughts exactly, music (rock) sucks these days. There’s gonna be a big breakthrough with a new sound. What that is, who knows..

write me back.

thanks,

Ken

Disaster post… Typos everywhere, misplaced commas. That should be “postwar economic expansion”

Interesting analysis. Maybe thats why new types of music keep coming out ie Rap, Rocountry, Hip Hop, etc. I noticed that many of my freinds who never listened to country before are going after it in a bug way.

Hey, you guys are missing the point. This is all in good fun but probably has a ring of truth. Take automobiles for example.

There was a time when you instantly looked at a car and you knew the make, model and year. They were unique. Today they all look the same. No innovation in the mass market arena. Music today is just as indistinguishable. You have your trivial trite country, hip hop, easy listening,etc. I say DRILL BABY DRILL! It’s worth a shot.

That parallel of the car industry could be taken even further into how terribly cars are made nowadays, made to fall apart (with the only source for parts being the manufacturer); whereas it’s rare to find an album with more good than bad songs, or at least more songs one doesn’t want to skip versus want to listen to.

Major difference between the two industries: one hasn’t needed a bailout- and it probably never will- for myriad reasons.

This whole graphic is merely measuring the general decline with age of those doing the judging of the songs. They like the songs they toked to when they were young, and now remember fondly. They didn’t have babies then. Now, they have houses with mortgages they can’t pay and divorce to contend with, and so they don’t love new music as much. Of course: they’re OLD. FREAKIN’ OLD.

I should know: I’m one. Actually, I do like some new music. And, I’ve been thinking lately that the Rolling Stones weren’t as great as we all thought. And, I do like Green Day. And Jet. And …

So, we’re not ALL old and dried up. Some can still FEEL THE MUSIC. The rest are old farts.

Love the article but it does need to be cleaned up a bit as the punctuation is sloppy.

This chart shows the prosperity of America. If you notice the decline of oil starting around 1970.. This is right before we abandoned the gold standard, opened up free trade, and started importing all we could. Now we import so much oil and foreign goods, that we have to export securities or national debt to balance our trade. It takes production to make a country wealthy and prosper. Free trade has sent all our manufactoring jobs overseas, so now we have to create play money (fiat) to be able to afford these oversea expenses.

this is the best worst website ever