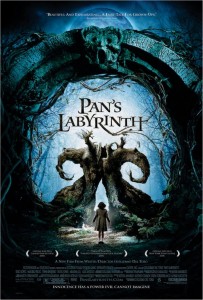

Pan’s Labyrinth, the gorgeous film by Guillermo del Toro, was on TV again the other day, and just seeing certain scenes brought all the feelings I had upon my first viewing flooding back. I should say at the outset that it is easily one of the best fantasy films in recent memory. Nevertheless, I left the theater with a niggling discomfort. Where the discomfort came from I didn’t know. Until now.

Big old spoilers after the jump.

First, some literary theory. Probably you’ve already heard of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth from his Hero With a Thousand Faces. It’s also called the heroic quest, although I prefer to call it the boy’s quest to distinguish it from the girl’s quest, which is markedly different. Part of the problem with Pan’s Labyrinth – and I’ll get back to that below – is that the story, for the most part, is a girl’s quest, but it ends in a boy quest way.

Here’s the general progression of the boy’s quest, as a review:

-Boy lives in happy childhood land

-Boy is called to the quest, refuses it, then is forced to accept it

-Boy is guided into the world of the quest – a fantastic wilderness world filled with magical creatures and scary people – by a helpful guide figure

-Boy gathers companions to help him with the quest

-Boy fights “the dragon” (the Bad Guy)

-Boy reunites with his father

-Boy is recognized as a hero (a Man), gets the girl, often becomes king, is in full possession of his powers, lives happily ever after as the Master of Two Worlds (the public “real world” and the fantasy/quest world)

It’s the plot of Star Wars and about a billion other stories. The main idea is that a boy becomes a man by entering a wondrous but somewhat threatening world, mastering its rules, and killing a bunch of things in it. His reward is kingship and a girl.

Pan’s Labyrinth, on the other hand, is mostly a typical girl’s quest, which goes like this:

-Girl lives in grey, unhappy/ambiguous childhood land

-Girl is called to quest, refuses it, is forced to accept it

-Girl is guided into the world of the quest – usually a world that is an uncanny version of her home life or a threatening wonderland that has no discernable rules – by a guide who is a phony or a trickster

-Girl sometimes, but not always, gathers companions. Often one of them will be an evil seducer figure.

-Girl fights “the dragon”

-Girl reunites with father (or mother) figure, finds him to be another phony

-Girl returns home, having learned a lesson about herself and her own powers

In short: the girl becomes a woman by entering a scary world, realizing the rules of that world are false, and returning home. It’s the plot of Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, Labyrinth, and a bunch of other fantasy stories that star female protagonists.

Let’s break down Pan’s Labyrinth:

-Ofelia lives in grey, unhappy childhood

-She is called to the quest by the Faun, an ambiguous trickster figure

-The Faun guides her into the labyrinth, which is both a scary fantasy world and, importantly, part of her home

-She gathers companions – the Spanish Maquis – who will help defeat Captain Vidal

-The girl succeeds in her first task but is seduced by the Pale Man (although, interestingly, he seduces her with food, not sex—but it’s the same thing in literature, right?)

-Ofelia fights her step-father (the Dragon), who is another phony, and steals her baby brother from him

So far, it’s basically the girl’s quest. Here’s where it shifts…

-Ofelia passes the Faun’s tricky test by dying instead of allowing her brother to be hurt

-Ofelia returns “home” to the Underworld, recognized as a hero, where she takes her rightful place as Princess Moanna

So what we have here is a girl’s quest that ends like a boy’s quest. Rather than return to a private, domestic space where she can get married and have babies, she is revealed to be a princess. By passing the test in the film, she has proven her worth and can lead her people in the Underworld.

So here’s my problem:

The movie is about the Spanish Civil War!

That is to say, the Good Guys are Republicans and the Bad Guys are authoritarians. So I have a problem that Ofelia’s reward is becoming an authoritarian (a princess) – and those monarchs are supposed to be Good Guys.

Del Toro’s downfall was replacing the girl quest ending with boy quest ending. The boy quest ending isinherently authoritarian. The boy hero gains mastery over the two worlds, thus proving he will be able to dominate them as a (hopefully enlightened) king. Although born under strange circumstances (often as an orphan or a bastard or a pig farmer or something), he shows his noble blood through the completion of his tasks and takes his “rightful place” on the throne.

How antithetical to republican values can you get? Thus, by using this standard ending, del Toro completely undermined his own themes.

Anyone else have this problem, or am I the only one? To read the reviews of the film, you’d think almost everyone else in the world disagrees with me. Here’s an article from Wired, which claims that the moral of the story is that fantasies save us from fascism, because they allow us escape. Ofelia can rebel against her step-father because she can imagine another world in which he is not in charge. She flees to the forest (a place of fantasy) and there meets up with the rebels who help her defeat her step-dad. In this reading, her death is a liberation from her terrible life to a wonderful land of fantasy. Roger Ebert likewise claims the movie is anti-fascist because Ofelia rebels against the authority of the Faun by refusing to harm her brother. Most of the other reviews go like this: “Blah blah blah… the power of imagination.”

All of these arguments are great, but they ignore the final scene. In my reading, Ofelia’s death is a liberation from Spanish fascism, but it’s only a liberation to the benevolent fascism of the Underworld. The somewhat happy ending of the parallel “real world” plot, in which the resistance fighters kill Captain Vidal, is still horrifying, because its final image is of a woman sobbing over the body of a dead little girl. The film seems to acknowledge that imagination can’t obscure the fact that, in real life, the fascists won the war. The power of the imagination didn’t beat the power of the gun.

A.O. Scott of the NY Times has an interesting reading of the film that is more ambiguous than the ones I referenced above. Here’s the beginning of his review:

- “Set in a dark Spanish forest in a very dark time — 1944, when Spain was still in the early stages of the fascist nightmare from which the rest of Europe was painfully starting to awaken — “Pan’s Labyrinth” is a political fable in the guise of a fairy tale. Or maybe it’s the other way around. Does the moral structure of the children’s story — with its clearly marked poles of good and evil, its narrative of dispossession and vindication — illuminate the nature of authoritarian rule? Or does the movie reveal fascism as a terrible fairy tale brought to life?”

The reviews above, and most of the ones I’ve read, lean toward the former; my reading leans towards the latter. Perhaps A.O. Scott is right in saying that the amazing thing about the film is that it allows both readings, balancing the two worlds just so to highlight the tension between the two. Or, it would if del Toro didn’t say afterwards that Ofelia really DID go to the Underworld and that last image wasn’t just a dying girl’s incoherent thoughts, thus ruining the wonderful equivocation. Oh well.

Anyway, what do you think? Did you read the film as a fairytale in which good was triumphant and evil was destroyed by the Power of Imagination? Or did you read it my way, as a good film that undermined its own themes by adhering to a fairytale structure that is inherently authoritarian? Or did you read it like A.O. Scott, as a film that was aware of and highlighted its own inconsistencies to point out the ambiguity of both fairytales and the Spanish Civil War? Or something else?

As far as I’m concerned del Toro can go screw himself with his little cop out to explicity. I watched the movie with my girlfriend and she was furious at me for making her watch a movie where a little girl dies at the end. Del Toro was most likely trying to appease those who reacted similarly.

Personally I’d have to align with the good Mr. Scott, since the ambiguities clearly contour the subjectivity/objectivity faultline without ever crossing over to either one. This reading is enforced by Ofelia’s return back to the Underworld, where she escapes her oppressors to, as you correctly point out, take upon herself a title customarily associated with oppression. This highlights a fundamental point, namely that the oppressed just wants to escape to somewhere that he is not oppressed – even if means oppressing somebody else in the meantime. This underlines the subjective aspect of oppression, while the little terrormonger of a scene whereby a little girl lies dead by the well epitomizes the harsh objective reality of fascism.

I’d say Pan’s Labyrinth is less a political tale than it is human tale, whereby the fascists and the republicans merely serve as symbols for the main factors which dictate our lives, the iron fist of social control (fascists) or the idea that somewhere out there, there might be people who would let you be as you are (the republicans), as you saunter along inside your little subjective world, for as long as you are able.

1. Monarchies aren’t necessarily authoritarian. The UK monarchy are essentially harmless duffers with extra-big giros.

2. Imagination and fascism are in no way incompatible. Look at say the sculptures of Arno Becker, the SS uniforms designed by Hugo Boss, films like “Triumph of the Will” etc.

3. Authoritarianism is not unique to fascists. Sure in the film the republicans are cute Robin Hood wannabes but in real life they were responsible for their share of massacres and brainwashing. NOT a whitewash of the fascists. Just more of a statement that both sides sucked hard. Except for Orwell. Who rocks like monolithic granite.

4. Dying doing the right thing totally does not give you a pass to the magic kingdom. That said it was by far the best possible ending (except perhaps her dying and fade to black: a rejection of the horrors of both worlds in an attempt to actually do the right thing).

5. I actually didn’t really read anything. There are (for me) films that make me want to read into them and others that just entertain. “Pans Labyrinth” entertained me so I just went with the story. Ken Loach films make me scream things at the screen (Usually along the lines of “You class ridden, outdated cock-nugget!”)

6. Pans Labyrinths only problem, like all film and TV is that it isn’t a 3rd series of “Rome”. More “Rome” dammit!

Shana, first of all, brilliant work, as always. Here’s the question at the core of your critique: Is a fairy tale monarchy equivalent to a real monarchy? Is every little girl who dresses up at Ariel for Halloween a mini-dictator? That’s a blog post in itself. Actually, it’s probably more of a master’s thesis.

But I’d propose that it’s a little bit of a stretch to equate fairy tale princesship with fascism. For starters, there’s no such thing as democracy in fairy tales. It’s just not part of the language of fantasy. So Del Toro sort of has no choice.

But more importantly, I think a child’s conception of what fairy tale royalty is has little/nothing to do with governance. I’m talking from personal experience here. Every night, my three year old climbs into bed and says, “Daddy, I tell you story now. Once upon a time there was Oliver, a prince. And he lived in a big big mansion, with an SUV. And it had a boat that was red, and lots of TVs…” and he basically lists a lot of stuff he’d like to own.

I don’t think fairy tale royalty is about dominating others. I think it’s about being special, and getting whatever you want.

Heh. That would be awesome. “Once you collect the 1,000 enchanted signatures buried in the roots of yonder REEDEECULOSSly-yonic Oak Tree, most-honored Lady Moanna, you shall take your rightful place as a candidate in Fairyland’s next U.N.-supervised election for Prime Minister. Which, as an independent candidate, you will most assuredly lose!”

I didn’t think about this movie quite as much as you did, Shana, but I’m sympathetic to your reading. I remember thinking that even if we accept the last scene in the underworld is “true,” it’s a pretty dark ending… The underworld is an exciting place to visit, but who would want to have to live there?

For me it was one of the 3 saddest movies i watched…it was tragic on the level of charachters and on other antiutopian – there’s no way out. Maybe there was a hint of communism, for both regimes require totalitarism, yet one is “good” (but then again comes the sad part- that its just a fantasy). But thats just overthinking it…

Fate of humanity aside, for the little girl there is no way out, even her fantasies are perverted and filled with frustrations and horror she gets from reallity, she can’t even imagine anything “new” she just escapes into something that is essentially the same, but there she finds what little comfort she can by making sense of the violence, by integrating it into a narrative, a familly drama. Little girls don’t know much about politics and they don’t care about ideals. What is important for them is their famillies (thats kinda fascist too) and stories, so that is the only tool she can use to make sense of the world (the oedipal drama, the war, the passivity of the supposed-to-be-protector mother). Its the psychotic structure, the traumatic “core” reappears in delusions, but in a way that the subject can deal with it (he/she is the chosen one), she is doing the quests, in and out of reallity, shes doing something about her problems, shes being a subject in the fullest way possible. But all hope is lost when after commiting her sacrifice, she just accepts her fate, there i think she dies again, she was the only subject in the movie but after the trial she truly becomes a woman like her mother and as a reward gets to be passive, and dead.

Interesting reading: the idea that Campbell’s monomyth is gender-coded in one way and a “girl’s quest” is coded in another is new to me, and I’m curious if there’s a theoretical source you are drawing from. It’s a good observation, and I’d like to read more.

With that aside, I have to say that the ending of the film didn’t bother me in the least. Then again, I read it as ambiguous: the fantasy realm isn’t strictly an escape from a nightmarish reality or a home to which Ofelia returns – it is both at once.

Furthermore, I don’t think I’d be satisfied with any reading that casts it purely as a victory for the heroine who comes back over the threshold or as a tragedy-cum-political-victory where the heroine perishes, leaving the emergence of a new state in her wake. The moral choice defies both the trickster guide of the quest and the fascist, two very different figures from very different worlds. The choice, and the ending, is a third way out – as it has to be.

Also, I have to echo the sentiment that monarchies and fascist regimes are not one and the same. Fairy-tale dominions that reside at the end of the quest, in particular, are earned by the outcast or disinherited – and not merely granted by inheritance alone, as is the case with the fascist’s blood-obsession.

It’s easy to say that fascism -> authoritarianism -> order and leave it at that (it’s politically true, after all), but in storytelling (including historical narratives) we think of fascism as a form of misrule. Fantasy and myth don’t allow for democracy, so the happy ending is the restoration of order in the form of a “proper” kingdom. Here, that kingdom is one where the imagination is free.

So I keep trying to figure out where I got this “girl quest” theory from. I definitely learned it sometime in college, but my memory is horrible. But I know it must have some basis in “real literary study” because other people on the Internet know about it:

http://virtual.clemson.edu/groups/dial/Oz/femoztax.html

There’s a bibliography on the bottom of the page, so I guess that’s where I got these theories from?

In any event, the fantasy girl quest that I outlined above is quite similar to the girl quest that you often see in certain kinds of 19th century Gothic novels. In those stories, the otherworld is an uncanny domestic space, the villain is some sort of evil father figure (usually an uncle or something), and the hero an adolescent girl whose emotions range from scared to curious.

Don’t ask me where I got that from either. I have no works cited page, sorry.

As for the democracy/fairy tale monarchy question, I do understand that the old fantasy stories lacked democracy by default. The question is whether or not a modern fantasy like Pan’s Labyrinth should follow the same form.

Ok, here’s an ending that could make us all happy. At the beginning of the film, the Faun tells Ofelia that the Underworld has been taken over by an evil prince (a mirror-world Vidal figure), and that she can only free her people if she can earn her right to return there. Then, the ending of the film has her returning to the Underworld as a princess, where she can take her throne and use her magic powers (or magic sword or whatever) to help the Underworld peasants rise up against Evil Fantasy Vidal and take back the kingdom.

In this new ending, Ofelia still gets to be a pretty pretty princess, and the story still follows an archetypal fantasy story form (now of the Fisher King, sort of), but I’m happy because now becoming a princess is wholly an act of rebellion that ends in freedom.

Uh… Campbell didn’t say just about any of this (or, rather, this is over-simplified to the point of not resembling what Campbell said). The link you provided to the Clemson website has just about the laziest and most useless summary of the Monomyth that I’ve ever seen.

First, the hero in a classic myth usually doesn’t come from a perfect world – the world is dying, which is why he or she must go on the quest. You forgot the step, following the fight with the Ogre-Father (also possibly a Dragon, but ‘Ogre-Father’ is a better way to describe the functional purpose of the character) and usually during the recognition by the Divine Father, of receiving the Divine Boon. The Hero takes this boon back to the world and revitalizes it.

What you seem to be thinking of is the “American Monomyth,” as identified by Shelton and Jewett in the mid-70’s. This one is marked by the perfection of the world, into which comes an evil force, ruining it. The Hero, likewise, comes from outside of the world, resolves its problems (usually in spite of the residents’ efforts, or lack thereof), and leaves again. It is by no means exclusive to (or even created in) the United States, but it is the most commonly-used construction in American media. It encourages the acceptance of violence as a purifying force and the pacivity of the populace in dealing with Heroes, for whom the rules should not apply. “Death Wish” and “Dirty Harry” are pretty much the paradigmatic “American Monomyth” films.

Second, when the Hero returns to the world and revitalizes it using the Divine Boon, the quest is not over. If the Hero ever stops returning to the other world, if he or she becomes too obsessed with the gifts gained in the other world to venture out again in order to gain further gifts (ie. a deeper understanding of himself/herself), then – as Campbell very clearly states – he or she becomes Holdfast, the new Dragon or Ogre-Father for the next hero. Further, he or she NEVER conquers the other world – it is unconquerable. It is the sum of all things that are unknowable. Psychologically (which is, after all, the main point of the Monomyth), the other world is the subconscious mind. The ego is incapable of understanding the conscious mind, let alone conquering it.

This entire article falls apart the second you realize that the “boy’s quest” doesn’t exist. It is one variation of the Hero’s Quest, which is much closer to your “girl’s quest” in that all of the steps are optional, and can occur in a variety of ways – there is NO step which occurs as definitely as this version states (also, you’ve left out several of the steps, such as the union with the Divine Mother, which occurs before or during the fight with the Ogre-Father, as she helps the Hero overcome him).

Read “The Hero With 1000 Faces.” Volume 9 of The Complete Works of Carl Jung would also help (start with the second book, “Aeon,” rather than the first, “Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious”), as would “The Morphology of the Folktale” by Vladimir Propp. “The Fantastic” by Tzetvan Todorov requires some leaps in logic to be connected, but is still valid. There are dozens of other texts on the subject, but these have the basics.

Can you tell I specialized in Myth in grad school?

Too tired to completely understand everyone’s fantastic response.

But, I think the fairy tale authoritarianism = real world authoritarianism is a huge stretch. It’s a fantastical world and all rules are bent anyway. That aside, the appeal to being a princess is to be loved by all and be able to do what you want, 99% of the time in regard to your own space. Have all the pretty dresses you want, a great family, find a husband that is your true love – not to determine rations or areas of land, rights and rules. The dream of a princess is pretty basic: autonomy, and the wealth to pursue that autonomy. I’d argue that the dream of a princess/queen is very different from a prince/king in that respect. It’s sad, but I think real that the next step for a little boy is to rule over others as well as himself, whereas for a little girl it is to rule over herself.

Your argument that Del Toro abandones his ‘girl quest’ theme in the final scene is well thought through, but I tend to disagree; Ofelia learns from the Faun that her place in the ‘real world’ is false: the Underworld she returns to IS home for her. The underworld king and queen are presented more as concerned parents (who just happen to be able to create all those portals) then as totalitarian figures of authority. The end-scene looks more like a ‘welcome home’ than an ascension to a position of power. Also, her victory over the Capitan is strictly personal, and the actual defeat of the fascists is accomplished by the guerillas. So I think you got hung up on the ‘noble birth’ thing too much.

So Mlawski, is Willow more of a girl’s quest? ‘Cause Val Kilmer is pretty seductive…

I’ve…never seen Willow. Don’t tell.

BOOOOOOOOOOOO!

*the moral of the story is that fantasies save us from fascism, because they allow us escape.*

John Hopewell states that during and after the Spanish Civil War people led a life in a ‘permanent state of evasion, of absence of reality, of withdrawal into fantasy’ or as Victor Erice (director of The Spirit of The Beehive and others films directed under the dictatorship of Franco) claims they became ‘exiled within themselves’.

It is possible to read the film in two ways. Either the fantasy underground realm existed and Ofelia’s quest wasone of self-discovery for her true identity. Or, that the fantasy works as a psychological reflection of the real world and is metaphorical of the spanish necessity to withdraw from the psychological trauma of the War itself by indulging in fantastical imaginings.

I believe the that both work alongside each other and that the underground realm exists. There is quite a bit of evidence to back this up throughout the film, although Del toro clearly tries to keep it ambiguous up to a point. Your problem with the fact that she is entering another realm which is run as an authoritatrain regime is understandable. However, the fact that the undergorund realm is shrouded in warm, sepia glow should demonstrate the fact that the monarchy of the fantasy world is not a dictatorial one like the cold blue lighting of Vidal’s fascist world,(hehe!) so i wouldn’t worry bout that one. The point of the story for me is that Ofelia’s unification with her rightful family is the manifestation of her true identity being fulfilled. Her quest is complete, and furthermore she had to oversom the amibuguous advice of the Faun and the violence of Vidal. By doing this she has demonstrated that she is independent and has claime the right to independence and has come of age. Furhtermore, i don’t really see a problem with mixing the boy and the girl quest, although i think you make an interesting point. However, it is more interesting that he subverted these quests as opposed to rigidly sticking by them. Plus, Del Toro loves to subvert standars customs. Such as the Gothic tradition in ‘Thje Devil’s backbone’ or the fairy tale in ‘Pan’s Labyrinth’

Cheers for the post, was an interesting read.