Ben Adams: HBO has announced a new series from the Game of Thrones producers, based on an alternate reality in which the Confederacy won the civil war and exists into the modern era. My Twitter timeline seems to be unanimous in thinking this is a Bad Idea. Despite having been a fairly big fan of alternate histories in my day, I’m mostly inclined to agree.

That said, here’s the question I want to pose: combine “Confederate” with “The Man in the High Castle” (and most other alternate history literature/movies I can think of), and I’m struck by the fact that almost all alternate histories ask the question “What if everything were worse?”

But isn’t it equally valid to ask “What if everything were better?” Aren’t there changes in history we could imagine making that would have made the world a better place? Why do our imaginations gravitate to the negative?

Follow up question: what “better world” alternate reality show should HBO make instead?

Mark Lee: Well, an America where slavery never took hold at all is the obvious starting place.

The first problem that comes to mind is the lower potential for conflict in this sort of story.

Jordan Stokes: Yeah, conflict is the trouble, right? This is probably why we tend to look for bad outcomes in our alternate histories. Same reason the news is always a cascade of atrocities. (Not to reopen that particular discussion.)

I feel like the America minus slavery story would be a hard needle to thread – what story are you telling? Is it set in, like, Atlanta? And if so… are there a lot of black people around?

Writing slavery out of American history means writing modern black culture out of American history. Which is not… comfortable.

Maybe the story you have to tell then, is what the black experience in America would have been, absent slavery? Sort of model it on other immigrant experiences?

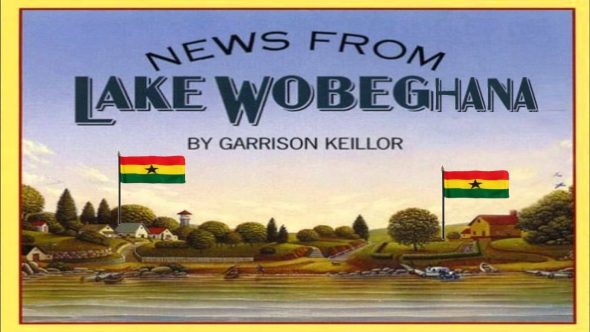

Like, what is the small midwestern town that relates to Ghana in the way that Garrison Keillor’s Lake Woebegon relates to to Sweden? But this seems like it would be easy to fuck up. In all kinds of excitingly godawful ways.

Matt Wrather: If other immigrant experiences are anything to go by, not having slavery — as unambiguously good as that would be — wouldn’t guarantee a smooth or even a particularly positive experience. Even the placid, repressed, and well-established Swedes of Lake Wobegon must have had ancestors who were denied jobs, run out of other towns, called “Sven” contemptuously, and so on.

The weakness in the “what if the bad guys had won” model of alternative history speculative fiction is that it seems designed to flatter the prejudices of its audience. It doesn’t really offer a window into the human experience, if that’s the kind of thing you go for in art; it offers a an opportunity to feel righteous. I mean, it’s all well and good to hate Nazis in Indiana Jones movies, but it’s another, presumably more satisfying, thing to hate Nazis in a show where the first superimposed title says “2017.”

“Well, what’s wrong with that?” you might justifiably ask. “Nazis are bad, right? Right, Matt?” And, yes, of course you’re right. When, last November, we ourselves were thrust into an alternate timeline, one of the consequences, I suppose, was that nothing goes without saying anymore, so just for the sake of completeness, I’ll point out that Nazis are bad.

But we don’t need a novel or a TV show or whatever to tell us that.

The problem, I think, is partly dramaturgical — beyond plot-level tension and suspense, there don’t occur to me a lot of interesting ways to tell stories with such unequivocally bad guys — but it’s partly a failure of moral imagination. Part of what makes Mark/Jordan’s proposal for a never-had-slaves alternative history so exciting is that you would have to imagine a completely different set of goods to build the world around.

“Bad guys win” alternative history doesn’t do this, and it’s less interesting for it. Evil triumphant is still evil, and you the reader get to be flattered because you know who the good guys and the bad guys are. (It’s easy: The bad guys are Nazis. Nazis are bad, just in case you’ve forgotten.)

Honestly Nazis are a terrible example, because it Godwins the argument I’m trying to make, which I guess is just that we should be uncomfortable when any work of art says to us, “You know who’s right about a lot of things? You!”

Lee: How about this idea from friend of the show Tim Swann?

I'd love to see what if Napoleon had won, with the moral and political complexity of a reforming autocrat sprung from a revolution https://t.co/3dnMd3nWAu

— tetrarchangel (@tetrarchangel) July 20, 2017

Peter Fenzel: I like it! “The Man on the High Horse” has a nice ring to it!

I’d compare negative alternative history to disaster movies, like Twister or Armageddon. Like Westerns, they’re about exposing how much of ourselves – and what we think is admirable about ourselves – is a product of comfortable or reinforcing circumstances.

What might we be like if we didn’t have that comfort or reinforcement? That’s sort of like asking, “What are we really like?” Then, maybe we also confront by association that we are not comfortable and not reinforced at times and this is what we are like in those times.

So, Twister is about a tornado, but it’s mostly about testing a strained marriage. I was going to ask what Twister would be like if the storm went back in time and strained the relationship before they were married, but then I realized that was Back to the Future. It’s about exploring what we’re really like, and what our parents were really like. It’s the difference between Red Dawn and Red Son—present disaster versus retroactive disaster.

Like the phrase “Guns of the South”—in my mind the most famous negative alternative history prior to the current spate—resonates with the modern South.

The big problem I think with doing “Confederacy Wins” or even “Slavery Never Happened” alternative history as a mainstream popular entertainment is that Black people don’t have the same sense of being comforted and supported by the history of slavery and emancipation such that removing it would be a interesting exploration, for them, of who they are now. That’s my guess anyway. I think white people who grew up in a post-Roots world especially don’t understand that slavery was more of an erasure than a history, in the form of wound it is. Separating people from their families, their names, their heritage, it’s very different from the immigrant experience of other peoples, let alone natives—and even then you don’t see the “Get out of here, Sven!” show Matt talked about turning heads. That’s not the kind of exploration of the past people want, unless it’s tied to a grander affirmation.

And that’s not even touching on the people for whom seeing the South winning would not be a disaster at all – that’s where it gets real unpleasant. So it’s a show idea that on the surface views its audience narrowly and myopically about what they find comforting.

To make a positive one, maybe you should look for negative things people find affirming and supportive. Like do an alternate history version of The Departed except the Red Sox won the World Series 35 times.

Stokes: This is sort of what I meant when I said that the “slavery never happened” show would be easy to fuck up. Slavery is a still-bleeding wound. To go in and erase that erasure, even speculatively, means poking at the wound. There are probably better and worse ways to do it, but people almost certainly get hurt.

If you squint at it really hard, the “Americans were too moral to ever countenance slavery” story is not thaaaat different from a Gone With The Wind-style “the slaves were actually happy” story. It erases the same trauma, just in a different way.

If you held a gun to my head and told me to write this, I would maybe do a short story set in the present day, where some black character has to put up with a series of microaggressions that increasingly get less micro. Maybe it climaxes with him trying to go vote in an election, only to find that his name’s been purged from the voter rolls or whatever.

And all throughout this his attitude is one of disbelief. He can’t understand why people are treating him like this. And it’s interspersed with him remembering stories about his ancestors — his great-great-whatever grandmother arriving at Ellis Island and whatnot — and how his family has been tied into this new version of American history. (In the flashbacks, the characters only encounter what you might call an ordinary level of anti-immigrant sentiment, which is why he doesn’t understand what’s happening now.)

The point, basically, is to put the real-world black experience through some ostranenie, i.e. taking something that is familiar and pointing out how deeply weird it is.

Done right, it would be a crushingly bitter (and non-comedic) satire. The concept seems like it would respond a lot better to a Twilight Zone treatment than to a Game of Thrones treatment… nothing about this calls for a bucket of tits and blood-soaked melodrama. But even so, it would be very hard to do it in a way that wasn’t pointlessly hurtful.

Next time: what does God think about all of this? And what if, we started thinking smaller about alternate history?