What comes after death? The NBC sitcom The Good Place tackles this thorny question head on, showing us the eternity in store for Kristin Bell’s Eleanor Shellstrop. In the pilot episode, Eleanor awakens to discover that yes, she is dead, but don’t worry, because “Everything is Fine.”

Eleanor is told by “Michael,” the architect of the Good Place, that she is one of only a select few humans that are allowed in – everyone else goes to the appropriately named “Bad Place.”

But what does it take to get into the Good Place? And what does this mean for our understanding of morality?

The Good Place/Bad Place dichotomy certainly seems to gesture towards a Christian-style afterlife, where the people who do good things go to heaven and the people who do bad things go to hell. But that represents an extraordinarily simplistic view of Christian morality, which usually emphasizes not only good or evil acts, but also a particular set of beliefs: the divinity of Jesus Christ, the supremacy of God, and the need for salvation. Indeed, many Christians believe that no amount of good actions can ever grant entrance into heaven – the only cure for sin is belief and devotion to Christ.

And the Good Place’s admission criteria, as initially presented by Michael, doesn’t seem to have a connection to any particular Earth-bound religion. Indeed, Michael tells us that no religion has ever got anything about the afterlife more than 5% or so correct.

Instead, we are told that the Good Place functions on an elaborate points-based system, where each and every action, good and bad, is tabulated throughout a person’s life and added up at the end. The people with the most points at the end got the Good Place, and everyone else goes to the Bad Place.

These points, however, only raise more questions. How exactly are these rules arrived at? Some stuff is easy: genocide = bad, donating money to charity = good. OK, got it.

But why is “failing to disclose a camel illness when selling a camel” worth -22 points, when the seeming (to me, at least) more serious “steal copper wire from decommissioned military base” only -16 points? And why are both of those acts, which are both concrete harms denying others of their property, less serious than the obnoxious but ultimately harmless “Overstate personal connection to tragedy” (-40 points)?

Ultimately looking at these discrete examples of point-earning behavior give us little hope of deciphering the system at work. Instead, we might want to look at the people that are allowed into the Good Place, and see what we can derive from the common ties that bind them together.

Here, I have to pause to remind you of the show’s premise: Eleanor doesn’t belong in the Good Place. Due to some cosmic accounting error, Eleanor, who was a not-so-great person that belongs in the Bad Place, has taken the place of a different Eleanor, who actually belongs in the Good Place.

And she’s not alone: Jason Mendoza, a.k.a. Jianyu, is not the Tibetan monk he pretends to be, but rather a miscreant D.J. from Jacksonville (one of the top 10 swamp cities in northern Florida).

Aside from those two, however, the denizens of the Good Place are uniformly and comically well accomplished: they are scientists who cured diseases, philatrophists who raised billions, human rights icons, etc. Tahani, for example, raised billions for a variety of global causes, in addition to attending prestigious schools and rubbing elbows with the her friends Taylor Swift and Bono. Each and every character we meet in the Good Place has some over-the-top-impressive resume of do-goodery.

Which is kind of interesting – there are no humble men or women who just lived a simple and kind life. No salt of the earth farmer who raised a family and helped her neighbors; no orphaned children who fought a valiant and inspirational struggle against a fatal disease.

Instead, each person seems to have a resume as long as your arm, with a lengthy list of accomplishment – diseases cured, causes championed. Mere ethical behavior doesn’t do the trick: one needs to have been impressive in some way.

This emphasis on accomplishment is underlined every time we’re told something about the “Real” Eleanor Shellstrop’s past: she’s not just a former refugee who donated her time to charity – she’s also an Ivy-league educated human rights lawyer that goes into the field to defuse landmines. It’s not just that she was kind – she was effective.

In short, if you want to get into the Good Place, it’s not enough to be good: you have to be great.

This is again somewhat at odds with many systems of morality and religion, which emphasize intention over results. Compare this points-based system of ethics with the teaching found in the New Testament, Mark 12:41-44:

41 Jesus sat down opposite the place where the offerings were put and watched the crowd putting their money into the temple treasury. Many rich people threw in large amounts. 42 But a poor widow came and put in two very small copper coins, worth only a few cents.

43 Calling his disciples to him, Jesus said, “Truly I tell you, this poor widow has put more into the treasury than all the others. 44 They all gave out of their wealth; but she, out of her poverty, put in everything—all she had to live on.”

By the standards of the Good Place, the widow probably got a few points for her donation – but that pales in comparison to the points that can be earned by those who were lucky enough to be born smart, or rich, or talented in some spectacular world-changing way.

OK, so basically we’re working with some sort of utilitarian morality: the more utility you create in the world, the more points you get. I can get on board with that.

But what about Chidi? Eleanor’s “soul mate” Chidi lived a relatively quiet life as a professor – he earned his way into the Good Place on the basis of his extensive study of ethical behavior, not through his good works. So is just figuring out the right way to act enough to get in? What exactly did Chidi do to earn all those points?

Well, see, that’s the thing. In The Good Place, there are some problems with the Good Place. You see….

******************SPOILERS FOR THE SEASON FINALE***************

What we’re seeing is not really the Good Place after all! In fact, the entirety of Season 1 has been an elaborate ruse by Michael, an architect for the Bad Place, to try and get the four main characters torture each other: Eleanor, Tahani, Chidi and Jianyu (real name: Jason Mendoza) are the only “real” humans; everyone else is a staff member of the Bad Place playing a role to mess with the heads of the 4 humans.

Which leaves us asking the question again: what does it take to get into the Good Place? In one sense, we don’t know very much: the points system created by Michael is probably all nonsense, created as part of the ruse to mess with our heroes’ heads.

And we’ve never seen the real good place, or what it takes to get in. We can be pretty sure it exists – Janet, we’re told, was stolen from there. But we don’t have any direct evidence of what it takes to get in. Insteadall we know is that these four people didn’t make the cut.

It’s pretty clear why Eleanor and Jason didn’t make it: they were not particularly nice in their human life, made little effort to improve, and in fact did some fairly horrible things along the way. It’s not hard to come up with a system of afterlife point-tallying in which they don’t make the grade.

But Chidi and Tahani represent two opposite ends of a spectrum: Tahani created massive amounts of utility in her life, improving the world through extensive charitable works. But her intentions, we are told, were bad: she was just trying to one-up her sister.

Chidi, on the other hand, had nothing but the best of intentions, working his entire life to determine what the most ethical decision would be. But he was totally unable to act on those decisions, dirving the other people in his life crazy.

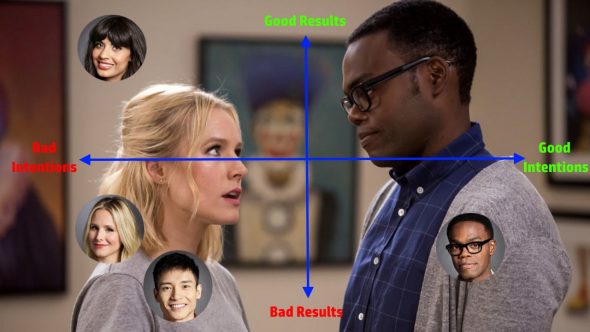

With those descriptions in hand, we can come up with a map of at the very least of what WON’T get you into the Good Place:

Eleanor was low-key awful throughout her entire life, but never really did anything THAT bad, so she’s in the lower left, a little further left than she is down on the graph. Jason did some pretty bad things (like lighting a speedboat on fire and trying to rob a store), but he’s such a goofball moron that it’s hard to credit his intentions as being all bad, so he’s to down and to the right, but they’re both well inside the lower-left quadrant.

Chidi tried to do good at all times, but at the expense of, you know, actually doing any good – so he’s all the way over on the right. Tahani did lots of great stuff, but only for the worst of reasons – so she’s up and to the left.

With that, we can conclude that the Good Place takes at least some combination of intentions and results – in order to make it in the afterlife, you have to have accomplished at least SOME good results. But that alone isn’t enough – you have to have achieved those results for the right reasons. You need to be up in the upper right – there’s no credit for running over a future Hitler in your car because you were texting while driving.

Ultimately, though, we don’t know what it really takes to get into the Good Place. All of our protagonists are flawed in at least some way, so we’re just left with the white space on the chart. Somewhere North and to the East of the Tahani/Chidi frontier you get the people that make in into the *real* good place.

So do good out there folks. But make sure you’re doing it for the right reasons!