If you’ve been following me on the social media, you might have noticed that I’m on a crusade to get everyone in the world to watch NBC’s Hannibal. I haven’t wanted to turn people onto a show this badly since Community season 2. It’s that good – and incredibly overthinkable!

The first season is now available to stream for $0 on on Amazon Prime

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

—Adam Smith

Is there a figure in today’s pop culture landscape that personifies conspicuous consumption like Hannibal Lecter? The Kardashians, possibly, or any of the Real Housewives, but to my knowledge none of them eat human flesh or look as good in three-piece suits, so point Lecter.

In most respects, the not-so-good doctor represents the perfect specimen of the homo consumericus. I won’t belabor this point, ’cause it’s obvious. Hannibal lives in an unnecessarily large and immaculately furnished house in the middle of Baltimore, a.k.a. The Wire Central. He drives a Bentley. He wears a $180,000 watch. Let me repeat that last one. He wears a $180,000 watch.

Frequent readers of Overthinking It know I’m a chart nut, so let’s start a little chart, shall we? Bullet point #1: Hannibal Lecter = the platonic Consumer:

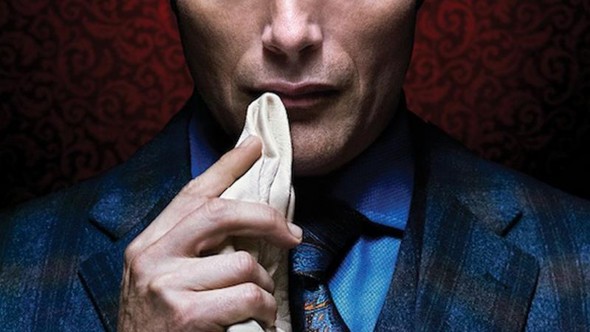

The point isn’t that Hannibal consumes – although, did you see that poster? – but that he does so conspicuously. As our pal Veblen once said, conspicuous consumption of valuable goods, such as art, is a means to reputability, and that reputability lets Hannibal get away with murder. It’s not for nothing that Lecter is constantly feeding schmancy meals to FBI honcho Jack Crawford (Laurence Fishburne). To paraphrase Chomsky, if you can’t beat the FBI by force, distract them with the consumption of fancily-prepared human viscera!

So, to update the chart:

The Lecter/Crawford relationship gets to the heart of Hannibal’s critique of today’s commodity fetishism. It’s evident that Lecter consumes – having a European actor play him emphasizes the character’s Draculean ancestry – but he also represents the alienation that is often a consequence of unfettered consumption. We all know that Hannibal sees people as objects (see: “I’m having a friend for dinner,” et al.), but none more so than service providers. In Hannibal’s mind, the original sin is rudeness, which notably is the most mortal sin a customer service worker can commit. We’re in America, after all, the land of service with a smile. And so in America, Hannibal Lecter chooses his nightly meal by flipping through the business cards of the many service providers who have wronged him by not engaging in the affective labor he paid them for.

The best part is, we’re meant to chuckle at these scenes. Who hasn’t had a bad experience with a service provider? The exchange of goods and services is supposed to be smooth, uninterrupted by annoying human emotions! How dare they be rude when we’re trying to buy something! So when I watch these scenes, I sometimes smile and think, “You go, Dr. Lecter! You cook those guys up good.”

What? I’m no saint.

By continually placing Jack on the opposite site of Lecter’s table, Bryan Fuller and the rest of the Hannibal team compel us to play compare and contrast – and add Jack to the chart we’re making. Although more expressive than Hannibal, Jack too represents the alienated capitalist. Jack also treats people as commodities – most strikingly, special agent Will Graham, whom we’ll get to in a minute. The main difference between Lecter and Crawford is that Lecter is an individual working toward his own self-interest, while Crawford is an agent of the state. Both kill to preserve the “lifestyle to which they have grown accustomed” (to steal the words of Lecter’s therapist Gillian Anderson Bedelia DuMaurier), but the FBI’s killings are state-sanctioned, while Hannibal’s are only sanctioned by us, the rudeness-hating audience.

Put a country’s elite consumers in an alliance with the state and you can slide into a frightening situation, partly because these two groups have the power to create consensus reality. In the hyper-capitalistic world of Hannibal, stylish consumer Lecter presents himself as the most rational of rational actors – this is the Marxian charaktermaske he wears, so well-crafted that it keeps him hidden even from himself. He also uses his substantial interior decorating and gardening skills to create other dimensions of reality to hide in, like the cavernous office/library that says, “This is what professionalism looks like,” and a perfectly-organized chef’s kitchen that says, “This is what sanity looks like.”

Likewise, Jack and the rest of the FBI imagine themselves – and, by extension, the state – to be rational beings. From their factory-like buildings, they attempt (and sometimes succeed) to use their knowledge of biology, chemistry, and by-the-book psychological analysis to reinforce law and order, CSI-style. The FBI authorities define themselves as logical, functional cogs in an economic/political machine, a.k.a. their version of “reality.” Along with Hannibal, they pathologize those who don’t fit into this mold.

oh hey will

Enter Will Graham. What’s the opposite of homo consumericus? Whatever it is, that’s Will. Will’s modest home in the middle of nowhere contains a mattress, a fishing lure, a boat motor, a pile of unleashed dogs, and not much else. Will is decidedly not a fan of, or provider of, service with a smile. He can barely provide service with a bit of eye contact.

Even so, Will’s not estranged from humanity in the same way Hannibal and Jack are. While Hannibal and Jack cut themselves off from others by treating them as commodities to be manipulated, Will cannot do such a thing. He can’t help but empathize with others, especially those experiencing the most extreme and disturbing emotions, which is why he constantly seems about five seconds away from a nervous breakdown. While Hannibal protects himself by wearing a mask, Will is a naked nerve – exactly the kind of person you don’t want working your assembly line, at the customer service desk, or, say, in the FBI.

No wonder Jack is constantly calling Will “broken” and sending him to psychiatrists. Jack wants Will to fit into his machine so they can get their jobs done as efficiently as possible. Broken cogs aren’t productive. With mild coercion and overt threats Jack exercises biopower, working to control Will’s mind and body so it is useful to him and the FBI. Hannibal does so, too, with help of unethical doctors and the power of gaslighting.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying Will is perfectly healthy or that he doesn’t need medical help. He does, absolutely – #somebodyhelpWillGraham. The problem is that he’s being sent to the wrong shrinks for the wrong reasons. He’s being diagnosed by people who are operating under this capitalist delusion that productivity, emotional detachment, and good taste are signs of sanity, and thus Hannibal is a well-bred fellow who doesn’t kill and eat people.

The transcendence of private property is therefore the complete emancipation of all human senses… The eye has become a human eye, just as its object has become a social, human object.

—Karl Marx

“Broken” is hardly the right word for Will when he is the only one with the ability to see through Lecter’s facade and puncture his constructed reality. As the platonic Consumer, Hannibal is associated with the mouth, which he uses to consume and to feed others lies. Will, on the other hand, is the Observer; his symbol is the eye. Throughout the first season, Will is repeatedly asked, “See? See?” and he does see through the artifice, even if he doesn’t consciously know it. Will’s authentic, organic connections to others, along with his apparently irrational leaps of logic, allow him to see beyond Jack and Hannibal’s consensus reality to a more naturalistic reality, which reveals that humans are more complex, emotional, and animal than the rational actors they pretend to be.

Put another way, Hannibal is a force of objectification that turns people and nature into symbols of use-value, while Will sees through status symbols to the nature and humanity underneath.

Example: Hannibal owns a bronze statue of an stag, a commodified simulacrum of nature. Again, Hannibal’s M.O. is to tightly control nature – and himself, everyone around him, reality itself – by processing it into status symbols (usually elegant food or visual art). Will has seen Hannibal’s statue but never actually noticed it. But his subconscious has. Starting in the first episode, Will has visions of a living demon-stag, his subconscious’ attempt to peel back Hannibal’s lifeless signifier to reveal the animal emotions it hides. As an artistic symbol, Hannibal’s stag statue is pretty empty; it only signifies its own economic and social value. Will’s demon-stag, on the other hand, is a symbol with weight; it points to reality. So Will’s psychological “brokenness” and surreal visions of nature direct him toward a truth nobody else can see: Hannibal’s bling is a cover concealing a message written in blood and dirt. That message says, “Hannibal Lecter is a monster.”

[Mankind’s] self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.

—Walter Benjamin

Will’s not the only irrational actor out there, of course. Hannibal takes place in a world where every other person is a psychopath and every third person is an artsy serial killer. The show’s big irony is that, although these serial killers are called anti-social, their aims are bizarrely pro-social. Pretty much every non-Hannibal killer in the show murders in a strange attempt to find true connection in an alienated, hyperreal world.

Take Garrett Jacob Hobbs. The killer in the first episode, Hobbs acts as a mirror to Hannibal, for, surprise surprise, Hobbs is a cannibal, too. But their cannibalisms stem from two very different impulses. Hobbs eats young women to honor them and feel close to his teenage daughter. Hannibal kills the laborers he sees as non-human to create a more refined world for himself and other elites. It’s the difference between a hunter who communes with nature and uses every part of every animal he kills, and the rich guy who kills deer so he can have a sweet piece of art above his fireplace, something to prove his superiority to both the viewer and the deer.

Which is not to say Hannibal loves art while the other serial killers shun it. It’s just that their conception of art differs from Dr. Lecter’s. For the most part, Lecter’s art is the art of obfuscation: his beautifully-plated pork loin is actually the product of murder; his black and white ear photographs draw us from the real ears he has in his pantry.

The other killers, on the other hand, make works of art to create an authentic connection with others. I’ll list some of their artworks so you can see what I mean, but if you don’t want to be spoiled, skip to the next paragraph. Consider the shop owner who turns a human body into a cello to serenade a man he admires. The pharmacist who creates a human mushroom garden hoping their roots will connect them. The young woman who cuts through human faces hoping to find a friend beneath what she sees as masks. The old man creates a human totem pole as a legacy – and so he can socialize at his victims’ funerals.

These killers’ macabre artworks aren’t meant to conceal but reveal. They are more than mere performances; they’re expressions. Their value isn’t a market value but an emotional one. Where Jack sees bodies as cogs or machines (tools of production), and Hannibal mostly sees bodies as status symbols or objects to be consumed, the other serial killers in the show see bodies as bodies, connected to each other by humanity, decay, and death.

These works of “art” are horrifying, obviously, and the show is hardly celebrating serial killers like Hobbs. Rather, it’s saying that, in comparison with Hannibal and the FBI, the serial killers are more more in touch with their humanity, more honest. I think of this quotation by Marxist philosopher Slavoj Zizek: “Precisely because the universe in which we live is somehow a universe of dead conventions and artificiality, the only authentic real experience must be some extremely violent, shattering experience. And this we experience as a sense that now we are back in real life.”

So, in an odd way, the killers’ gruesome works of art wake us up – emotionally, spiritually, aesthetically, morally. At least, they do so for one man. Although 99% of the time Hannibal presents art as a status symbol and a means of obfuscation, occasionally the other killers’ creativity inspires Hannibal to express himself in seemingly more authentic ways. For example:

“Nude With Antlers, Sans Lungs”

This piece from episode 1, an homage to the work of Garrett Jacob Hobbs, is the first in Hannibal’s “Love Me, Will” series. This is the first time that Hannibal takes a break from throwing up masks so he can say without words, “Look, Will! I’m the Chesapeake Ripper! Can’t you see the real meeee???” Hannibal has made similar artworks out of bodies before, but that was theatrics, a way of boosting his own ego, humiliating his victims, and thumbing his nose at the police. But here, Hannibal’s putting himself at great risk of being caught, apparently in the hopes that he can have a real connection with Will. Arguably, his wish is that Will can break through his world of lies and alienation so he can scoot over to the other side of the board:

Could it be that Hannibal’s tired of being a consumer and objectifier and is ready to admit he and others are human? Or are Hannibal’s newest “artworks” simply another method of obfuscation, a way to play mind-games with his boy-toy Will? How long can Hannibal keep eating grumpy members of the proletariat, anyway? And can somebody, anybody, help Will Graham?

Find out this season on Hannibal, and sound off in the comments. (Just don’t forget to label spoilers if you’ve got ’em.)