Don’t touch those, Finn, you don’t know where they’ve been!

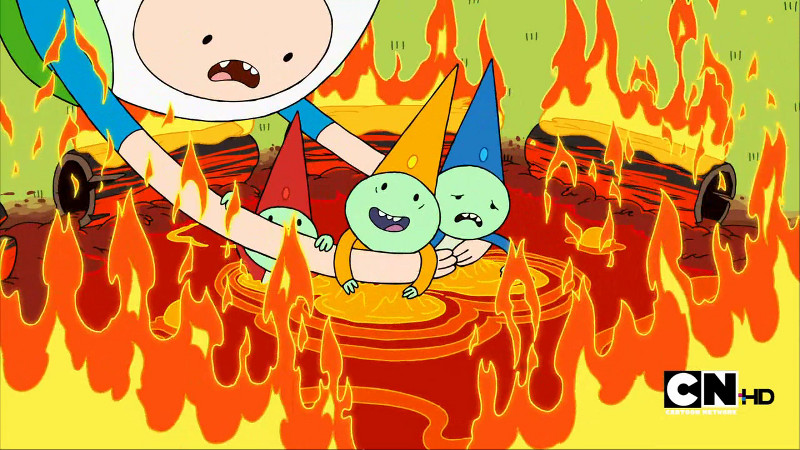

There’s a telling moment in the early Adventure Time episode, “The Enchiridion,” where Finn meets some gnomes trapped in a lake of fire. He rescues them, of course, because Finn’s a hero, and helping the unfortunate is what heroes do. But as soon as he does, the Gnomes start blowing up old ladies. There’s a message here, I suppose, about the fact that the unfortunate are not necessarily virtuous. But that’s not really what the show is trying to accomplish. Rather, the show is taking an old established fairy-tale plot and turning it on its head. The way the plot’s supposed to work (as it does in fairy tales like “Diamonds and Toads,” “The Mouse and the Lion,” and countless others), is that Finn goes out of his way to help the gnomes in act one, and then they show up in the nick of time to help him out in act three. Not so in this case: instead, they turn out to be psychopaths, and Jake stuffs them right back into the lava. The same plot, and the same reversal, inform the episode “Freak City,” in which Finn meets a hobo who asks him for food. Finn only has a sugar cube, which he’s loath to part with because he’s “freaking all about sugar.” But he’s even more all about helping people, and besides, as Finn puts it, the hobo is “probably secretly an elf who will reward us for being nice.” As it turns out, the hobo is the Magic Man, and rather than rewarding Finn, he curses him, turning him into a giant foot. Like many fairy-tale curses, this one can’t be reversed until Finn learns a valuable life lesson. But in this case, the lesson is that the Magic Man is a total jerk.

This kind of treatment of standard children’s plots is endemic to the show, at least in its first season (which, in that it’s all that’s on Netflix, is all that I’ve seen). In “Tree Trunks,” Finn and Jake go on an adventure with their pal Tree Trunks, who looks like a tiny, wrinkly yellow elephant, and talks and acts like Rose from the Golden Girls. At first, Finn and Jake are anxious about adventuring with her, because she’s an old lady with no combat skills and a weak heart. But when they encounter a menacing wall of flesh, Tree Trunks realizes that it’s not a bad wall at all: it just needs a little love. She gives it some stickers, it learns the error of its ways, befriends them, and then in the third act comes back to scratch all of that, after she gives it the stickers, it tries to eat her, and Finn and Jake have to kill it with violence. In “The Witch’s Garden,” Jake loses his magical powers because he steals a donut from a witch. All he has to do to get them back is apologize, but he’s too proud to do that. Eventually Finn gets in serious trouble, and Jake weeps tears of remorse in front of the witch, who tells him he’s learned his lesson and grants him his powers — at which point he knocks her down, steals another donut, and runs off to save Jake, proudly shouting “I’ve learned nothing!” In “Finn Meets his Hero,” Finn decides that rather than jump-kicking evil in the face, he’s going to try to find nonviolent ways to help people in his community. This goes UNREASONABLY poorly, and causes no end of destruction. Contrariwise, in “Henchman,” Finn is forced to help the Vampire Queen Marceline carry out a series of apparently evil actions (such as raising an army of the undead), which all wind up making people happier.

Adventure Time hits this particular note so frequently, and so hard, that it would be easy to read the show as a kind of libertarian fable about the law of unintended consequences. Ameliorist, interventionist social policies just end up hurting the very segments of society that they were trying to benefit. If Donny the Grass Ogre is pulling vicious pranks on a village full of tiny house-people, we can try to reform Donny by giving him an education, pants, and a future… but it will turn out that Donny’s body odor was the only thing protecting the house-people from a far more dangerous antagonist, a pack of Why-Wolves. (For Donny, read “Avon Barksdale.” For “tiny house-people,” read Baltimore. For Why-Wolves, read “Marlo.”) The only intervention that has never backfired on Finn and Jake is physical violence, which is in keeping with the sort of libertarian ideology that wants a miniscule federal government with a whopping defense budget.

But I don’t think the show is really libertarian, deep down. (We see the failure of ameliorist policies, but we don’t see the free market providing a solution to the same set of problems.) Rather, the driving message seems to be that, because trying will only make things worse, we are morally licensed to not try. Confronted with a problem like Donny the Ogre — a transparent allegory for urban blight — the appropriate response is to ignore it and go blithely on your way. (This is arguably a canny message for a franchise that depends on it’s audience deciding to get high and watch cartoons all day.) And even this is probably reading too much into the show. The constant reversal of standard fairy-tale plots is probably motivated by nothing more than a sense of formalist play. The show is anti-ameliorist, and promotes slacking, precisely because actual fairy tales are rigorously ameliorist, and promote action. The reversals aren’t really meant to have meaning: they’re reversals for reversal’s sake, because reversals are awesome and funny.

This kind of fast-and-loose play with convention is a big part of what makes Adventure Time appealing to its sizable adult audience. If you’re like me, and you grew up reading the Andrew Lang collections from cover to cover, it’s pleaurable (and in a weird way validating), to watch a bunch of clever writers playing with those particular toys. But the show is ostensibly pitched to children, and so to evaluate its malformed fairy-tale plots, we have to examine the role that those plots play for children.

There are two general explanations for this.The first is that children are stupid, with tiny pathetic brains that are incapable of processing moral ambiguity. If you make them think, they’ll get angry or bored, so the story has to be as simple as possible. Eventually, they get smarter, and demand more complicated moral systems. The second theory, which is more interesting, is that children are bastards. Another aspect of fairy tales’s moral simplicity is the way that they conflate goodness with physical beauty. In Cinderella, the wicked stepsisters are also the ugly ones. Some later versions try to identify a causal link, making one of the stepsisters too fat because she’s a glutton who eats bonbons all day, and making the other too thin because she’s vain and spends all day looking into mirrors, but these are accretions, added to make adult sense of a fundamentally childish story-logic. The real reason that the good characters are hot, according to the child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, is that goodness, on its own, is not enough to make children care about the hero. The relevant question for the audience is not “which of these characters is admirable,” but “which of these characters do I actually admire?” And because children are hideously amoral little beasts, by and large, the answer is not “the one that’s most good,” but rather “the one that I want to be like,” which is the rich one, the hot one, the one with narrative agency. (If heroic characters lack any of these qualities at the beginning of the story, they eventually get them at the end.) Bettleheim’s contention is that the social function of fairytales is to program children to associate morality with these more obviously desirable characteristics: first the child identifies with the hero, and then, in Bettleheim’s words, “the inner and outer struggles of the hero imprint morality on him.” Generally, this programming is so successful that we need another round of it (again, typically around the end of middle school) to teach us that hotness does not necessarily equal goodness.

It’s not so much that these three are GOOD looking, as that the rest of the cast, uh, has no alibi, if you catch my drift.

If you read the plot summary of Adventure Time, and look at the conceptual art, it seems like a Bettleheimian fairy-tale of the first order. Finn, Princess Bubblegum, and Marceline — three of the major protagonists — are a lot more beautiful than the rest of the characters. (Jake fits in more with the rank and file, but Jake isn’t really a focalizing character in the same way.) More importantly, they’re cool. One of them plays a bass that is literally an axe, another has a wicked awesome sword… you get the picture. We have all kinds of reasons for wanting to identify with them. The main villain, on the other hand, the Ice King, is not only a jerk, but a giant loser. And it’s primarily the fact that he’s a loser (rather than the fact that he is, in a waffly, PG-13 kind of way, a serial rapist), that prevents the audience from identifying with him. At one point, when Finn and Jake are playing ninja, they learn that the Ice King is way, way into ninjas, and Jake actually wonders aloud whether ninjas must therefore be lame by association. This is precisely the kind of identification-and-rejection mechanism that Bettleheim describes.

So much for Adventure Time’s characters. As for the plots, however…

When people try to explain what Adventure Time is about, they tend to suggest that the Ice King is constantly kidnapping princesses, and Finn is constantly saving them. This would give us good, and evil, and a reason for preferring one to the other. But if you actually sit down and watch the show, that basic plot actually plays out but rarely. Rather, what we see over and over again (as described above) are subversions of basic fairy-tale narrative logic. When Finn tries to be good, it usually backfires spectacularly. It is only in his attempts to be good, in fact, that Finn is, rather than a strong, cool, and capable character, a perennially weak and frustrated one. (We might put it like this: Finn is just about as good at being good as the Ice King is at capturing princesses.) We still identify with Finn — but his goodness, which for Bettleheim is the entire point of our identification with the character, is constantly played up as trivial, or unimportant, or accidental, or even misguided, thus breaking the link between coolness and goodness that the fairy-tale’s moral content depends on so heavily. Thus, Adventure Time only has moral content in that it makes mock of the sort of moral content that children’s entertainment generally has.

And therefore, although Adventure Time is popular with children, it’s not really a children’s show. I don’t know if I would show it to my kid, if I had one. When Ricardio the Heart Guy describes the super-best-friend-massage-technique as “entirely consensual,” I just about died laughing. But I really wouldn’t want to explain to an eight year old why that’s funny. We’ll give the last word to G.K. Chesterton, whose ideas about fairy tales are quite similar to Bettelheim’s (although proceeding from radically different assumptions):

Beautiful, wise, and witty lyrics like those of Stevenson’s “Child’s Garden of Verses” will always remain as a pure lively fountain of pleasure–for grown up people. But the point of many of them is not only such that a child could not see it, it is such that a child ought not to be allowed to see it–

The child that is not clean and neat,

With lots of toys and things to eat,

He is a naughty child, I’m sure,

Or else his dear papa is poor.No child ought to understand the appalling abyss of that after-thought. No child could understand, without being a snob or a social reformer or something hideous, the irony of that illusion to the inequalities and iniquities with which this wicked world has insulted the sacred dignity of fatherhood. The child who could really smile at that line would be capable of sitting down immediately to write a Gissing novel, and then hanging himself on the nursery bed-post.

A child who watched Adventure Time would not really understand Adventure Time. And if they did, they would not really be a child.