I once read that every genre of literature has, at its core, a question. In a romance novel, for instance, the question is, “Will the protagonist find her happiness with her true love?” It doesn’t matter that we know going into it that the answer is, and always will be, “yes.” More important is how the question is answered. Other genres have other overarching questions. A mystery, at its core, will always ask, “Why did this murder occur?” A fantasy novel will often (but not always) ask, “Will good triumph against evil?” A children’s book will tend to ask something along the lines of, “How will this child grow up?” These questions will not always be asked explicitly, nor will the answers always be pat and obvious. But they are there.

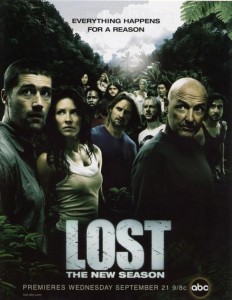

Lost does not fall under any of these genres. So, then, what genre is it? I think we have two options. Option one is: Lost is a postmodern ontological mystery (much like, say, Sartre’s No Exit). Option two is: Lost is a work of science-fiction. Or, I suppose there’s always option three: Lost is both.

So far, we have more proof that Lost is an ontological mystery. An ontological mystery is a mystery that asks not, “Why was this person murdered?” but, “Where the hell are we? What is this place the author set up?” This question came up explicitly in Lost’s pilot. Charlie said, “Guys. Where are we?” That is the main question of season one. I will get to the answer, or lack thereof, to that question in a moment.

The other option, which some of you suggested in your comments on my earlier entries of this series, is that Lost is a work of science-fiction. The strange metallic sounds mixed in with the roars coming from the island’s Monster in the season finale strongly suggests there’s sci-fi afoot. (Yes, I’m crossing my fingers for robots. Didn’t you read that comment I made on ShadowBanker’s zombie article?) The major question a work of science-fiction tends to ask is, “Based on where we are now, where are we, as a species, going?”

Let’s consider the “where are we?” question first. So, where are we? What is the island? Why are the characters there? What’s the point?

I’ve already given several potential answers. The island is purgatory. The island is Lord of the Flies, flipped upside down. The island is the heart of darkness. The island’s a scarier version of the planet in Star Trek TOS’s Shore Leave. Or my favorite answer, the rationalist answer: the island’s just an island.

Almost every character has come up with a potential answer for that question, too. The island called them there for a reason. The island’s a miracle. It’s fate; it’s luck; it’s a curse; it’s punishment; it’s a test. Jesus. What isn’t the island?

I’m getting to the point where I’m starting to wonder if the island has any meaning at all. Before I give you some evidence for that reading, though, let me remind you of what episodes I watched this week.

Episode 16 (“Numbers”): In the past, Hurley was cursed with luck, both bad and good, after playing some mysterious numbers in the lottery. In the present, he tracks down Rousseau, who also has no idea what the hell the numbers mean.

Episode 17 (“Deus Ex Machina”): In the past, Locke’s dad conned him out of a kidney. In the present, Locke has spooky visions about Boone, and they both find a plane. My notes say, “Haha, Boone’s going to die in a plane crash.”

Episode 18 (“Do No Harm”): In the past, Jack got married? (Lame flashback, guys.) In the present, haha, Boone died in a plane crash.

Episode 19 (“The Greater Good”): In the past, Sayid (almost) convinced a friend to suicide bomb himself so he (Sayid) could get information about his would-be girlfriend. In the present, Shannon tries to kill Locke, but Sayid stops her.

Episode 20 (“Born to Run”): In the past, Kate got her would-be boyfriend killed. (Yawn. This flashback, like the one in “Do No Harm,” went on for too long.) In the present, Sun accidentally poisons Michael (I totally called it, too! My ego tells me I must point this out). Sawyer reveals to the islanders that Kate is a criminal.

Episode 21 (“Exodus: Pt. 1”): Rousseau says the Others are coming for Claire’s baby and leads a bunch of the crew to the Black Rock (which is an old slaving ship—sweet!) to get dynamite to open the hatch. The rafters leave the island.

Episode 22 (“Exodus: Pt. 2”): Rousseau steals Claire’s baby; Sayid and Charlie bring him back. Arzt blows himself up. Disregarding Hurley’s protests, Locke opens the hatch. The rafters find a boat and cheer. I say to the rafters, “Why are you cheering? Haven’t you been watching this show? Nothing good ever happens, ever. Watch. Something terrible is going to happen right now.” And it does.

*****

The Crying of Lot 4 8 15 16 23 42.

I want to focus mostly on episodes 16 (“Numbers”) and 17 (“Deus Ex Machina”). “Numbers” was the first indication to me that the answer, if you will, to Lost might be something along the lines of, “There is no answer.” Or: “all the answers are equally true,” which is pretty close to “there is no answer.” The whole episode concerns Hurley’s obsessive search to find out the meaning of these mysterious numbers (4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42, 4, 8, 15, 16, 23, 42, 4, 8, 15, 16…). They bring bad luck. Or do they bring good luck? Hurley and Rousseau think the numbers led them to the island. But then we see in “Exodus” that fate was conspiring to keep Hurley OFF the island. Plus, it’s canon that Rousseau’s kind of a nutjob. …And also it’s highly suggested that Hurley suffered from some mental illness, as well.

Hurley thinks the numbers are a curse. Sayid thinks they’re coordinates. Mrs. Toomey thinks they’re a coincidence. Leonard Sims think they’re a combination to Pandora’s box—which actually makes a lot of sense when you notice that they’re printed on the side of the hatch, which Locke says is filled with (among other things) hope.

AAAAAAAAAH WHAT THE HELL ARE THESE FRIGGIN’ NUMBERS??!?!

…Sorry. Didn’t mean to go off on you like that. I think you can probably see where I’m going here. Just as the island on Lost has about a bazillion possible in-canon meanings, so do these crazy numbers. Like Hurley, once we know the numbers, we start seeing them everywhere. The bounty on Kate’s head is $23,000. Jack sat in row 23 on the plane. There are four people on the raft. Ana Lucia sat in seat 42F. Blah blah blah blah blah. Suddenly I feel like Jim Carrey in that movie, The Number 23. Or a character in a Thomas Pynchon novel, trying her damndest to properly interpret symbols and clues that ultimately are meaningless. Or I live in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, finally knowing that the answer to life is 42, but unable to find out the question.

And because I’m a nerd, I must admit I also thought of the 47 theme in Star Trek episodes. The writers mention 47 all the time. And you know what it means? Nothing. Absolutely nothing. The writers put it in there as a game. I’m sure Locke would find that quite appropriate.

According to the critics, the number 23 signifies "sucky movie."

So I started thinking: “What if the numbers don’t mean anything?” I mean, of course they mean something to Hurley, and of course they mean something to whoever inscribed them on the side of the hatch. But maybe, inherently, they have no magic meaning at all. The only meaning is what the characters ascribe to them.

It gave me the idea that maybe Lost is not only an ontological mystery (“Where are we? Why are we here?”) but also part of a smaller genre. I’m not sure what to call this genre, exactly, but I can name a bunch of texts that fit the form. It is a postmodern genre for sure. It is a genre that calls into question the act of reader interpretation as an act of psychosis. The main question of these texts is still, “Where are we and why are we here?” The answer, or the moral, of these texts is, “There is no answer, and you are crazy to be looking for one, even though I, the author, put all these hints here to point towards one.”

I’m talking too much in generalities. Let me give you an example: Alan Moore’s From Hell. No, it’s not at all like the shitty movie of the same name. It’s actually a wonderful comic. And it’s quite layered. It is about Jack the Ripper, mostly from Jack the Ripper’s point of view. Like Lost, it’s full of mystery, flashbacks, and references to other works of art. So Moore is tempting people like me—the English majors, the compulsive readers. The Overthinkers, in other words. There are hints everywhere, historical connections. It is a book that makes you want to think about it.

And then what does Moore do? At the end, he reveals that his Jack the Ripper, too, is a reader. But he doesn’t read a book. He reads the world. He looks at a map of London and decides the whole city’s a conspiracy. Sites are built on certain points on the map for certain reasons. He must kill people in those places to fulfill some mystical goal. (Moore, of course, is also winking about modern-day Jack the Ripper conspiracy theorists. You can go to Wikipedia, if you want, and read theories about twenty-seven different suspects believed to be Jack the Ripper. I’m sure they’re all true.)

Thus, the moral of From Hell is, “There is no meaning to life but the ridiculous ones you make up in your heads. Thinking otherwise is insane.” This is a moral I, a postmodern atheist, somewhat appreciate. But as a former English major and Overthinker, I have to admit it makes me grumbly. Why put the symbols and metaphors and allusions in there if there was no meaning besides, “there’s no meaning”? To screw with our minds, that’s why. Damn authors.

Similar, but not entirely the same, is August Strindberg’s Miss Julie. (European fin-de-siecle drama in the house, yo!) Nineteenth century spoiler alert: Miss Julie dies. More specifically, at the end of the play she (presumably—it happens offstage) kills herself. Which is why lots of people accuse Strindberg of biting off of Henrik Ibsen, the other European master of plays about women killing themselves, and why, I think, the two playwrights never got along.

Why does Miss Julie off herself? The play gives a myriad of answers. It’s due to her feeling hopeless as a woman in a man’s world? Does she do it out of fear? Is it because she’s humiliated over breaking her engagement? Is it because she just had sex with a man of low rank and is embarrassed by it? Is it because that man just killed her beloved pet bird? For God’s sake, the play at one point even suggests she does it because she’s on her period.

The whole point of the play is to debunk the myth perpetuated in other works of the time (and works now, especially on TV and in the movies) that people are psychologically simple, and that any act they do can be explained by one important thing in their pasts. Like: he’s a supervillain cause his mommy never loved him. Or: he’s a superhero because his parents were killed by a criminal. Easy, one-to-one relationships.

Miss Julie says, “No. Humans aren’t that simple. Life isn’t that simple. There is no easy answer here, and I, August Strindberg, will not give you one.”

Suicide and illicit sex were all the rage in 1880s pop culture. Well, not really.

Maybe that’s what Lost is doing, too. In this first season, the characters gave me many different answers. But none of them seemed sufficient. It’s possible that, at the end of it all, the answer will be, “You were all right. There is a scientific, realistic explanation for all this, but that answer can also be explained by religion or luck or fate or whatever you want to call it. Life can be all of the above.”

Or, it can be along the lines of From Hell: “You were all wrong. There is no meaning to this island. It’s just a bunch of random events. Just like life. The only meaning is the one you provide for it. But if you stick too much to that one interpretation, beware, because people might start thinking you’re a whack job conspiracy theorist who repeats numbers to himself over and over. I’m looking at you Hurley. And don’t think you’re getting off easy, John Locke.”

This “all answers are equally valid or invalid” theory shows up again in Episode 17 (“Deus Ex Machina”). You can read the episode as a Christian allegory: Locke’s Jesus (Yes! I so called that!), his dad’s an asshole God, the island is Hell, and Locke’s breakdown at the end is his, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Or, you can read the episode in a naturalistic way: Locke’s a poor, sad man; his dad’s a plain old asshole; the island is an island; and Locke’s breakdown is a symptom of his plain old human frailty. The symbolism of the episode also holds this duality: Virgin Mary statues that are filled with heroin, a Nigerian priest who’s really a smuggler, a plane in the woods that’s both a sign of hope and of tragedy.

Both readings, the spiritual and the naturalistic, make perfect sense. More importantly, they make sense at the same time. The show seems to be suggesting that everyone’s interpretations are equally valid. Or equally invalid, as the case may be. Maybe all the interpretations of the island make sense together because they’re all false. As in Miss Julie, the many possible answers could suggest a moral of, “There is no one simple answer. The world is too complex to be read this way.” Alternatively, Locke could go even more crazy, thinking that he’s part of some “design” like his mother said, suggesting a moral of, “There isn’t even ONE answer, and if you think there is you’ll go crazy like Locke.”

Yeah, but…

The trouble is, if the moral of Lost is, “the world is too complex to have just one answer,” that can be a big letdown. Because, let me tell you: after watching twenty or so hours of the show, I want some real answers. I don’t want any wishy-washy, postmodern crap. I want there to be a big reveal where some God-figure (maybe Locke’s dad?) or some villain comes out and explains it all, in excruciating detail. At this point, I don’t particularly care if the island is explained by science, faith, luck, magic, sci-fi, or something else I haven’t thought of yet. I just want a solid answer. Infodump me, ye mighty infodumpers!

It seems to me from my position at the end of season one that Lost has two options. Option one: it can continue on this path of having multiple possible answers to the questions of the island and not come down on any one definitively. If that is the case, I will continue to watch, but I will understand why many people gave up midway through. As they say, gratification delayed I can deal with. Gratification destroyed I cannot. The writers can continue to give out fake answers with an eyedropper, consoling us with images of the game, Mousetrap, to suggest that each fake answer is a piece to a larger puzzle. That is fine as long as it lasts. Because, unless they eventually pull back and show us what the puzzle looks like, the audience is going to get really freaking frustrated. And by “audience,” I mean me.

It's like a metaphor, man. For our lives.

Option two: I was wrong, and there IS one overarching theory that answers all the questions of the series. (It’s funny that Lost’s fans keep hoping for this ending, because when the U.S. version of Life on Mars ended this way, everyone was super angry.) If that’s the case, they can either delay that answer until the end of the show, or they can give us the answer (or at least a major part of it) soon.

I can hear some of you now. “No, they couldn’t reveal the nature of the island too soon! That would ruin the premise of the show!”

That is false. I point you to exhibit A: Burn Notice. Burn Notice, readers of the blog will know, is a show I love. A show a lot of us love. The major question of the show was, “Who burned (i.e. fired) Michael Westen the spy, and why?” Each episode, Michael would find bits of clues that were, we were assured, building up to form a bigger picture. But the process was agonizingly slow. I began to wonder, “Do the writers even know who burned him?” I’m sure others were thinking that, as well.

Then the writers did something magical. In the second season, Michael found out. He found out who burned him. He found out why they burned him. He doesn’t know everything about these people, but now he, and the audience, have the basic answer to the major question of the show.

Did the show end after that? No. Did the show take a turn for the worse? No, and double no. Can you believe: the show got better? Because it did. I’m sure it would have gotten better anyway, because the writers have gotten their grooves on, but still. The show now is superb.

But if the major question of the series is answered, why watch the show? I watch the show because it’s been replaced with a new question. Potentially a better question. Now the question isn’t, “Why is Michael here?” He knows that. Now the question is, “What will Michael do now?”

Remember I was talking about ontological mysteries versus science fiction before, way at the top of the page? In a science fiction text, sometimes the question is, “What are we doing here?” But more often, the question is, “What will we [as a race, as a culture] do next?”

I know Lost’s seasons two through six are already written and filmed, but from where I’m sitting on the tail end of season one, the writers have a load of potential here. They can give up the ontological mystery by answering the question of what the island is and why the characters are there. We asked those questions throughout season one. It was fun, but it’s getting to be enough. Now, the best thing they could do would be to make Lost more science-fictiony. I don’t mean it has to have more robots, although that could certainly help. I mean they can focus more on the question of “What will they do now?”

A scene from Lost, season 2? Please?

For instance, let’s say in the second season, they find out the island is actually The Lost World, and The Monster is a T-rex. (I know this is a silly example… or do I?) By the end of the second season, they know The Lost World was built by a corporation attempting to make a dinosaur zoo. They also learn the corporation was taken over by a madman who engineered a plane crash so the dinosaur zoo would have human visitors.

Great! We have an answer to our questions. It may be a dumb answer, but at this point I’ll take almost anything. Now the question is, “Now that the characters have this information, what will they do? How will they react? Will Locke continue thinking it’s all an act of God, even though it’s been proven otherwise? Will Jack go on a mission to save the girl from the first Jurassic Park movie, who is trapped by the T-rex as a surrogate child? How will they escape to tell the world about the dinosaur threat?”

Will this new show be less mysterious than the first season of Lost? Undoubtedly. Will it be less exciting or suspenseful or interesting or emotional? Not necessarily. Can the show still be about human nature and faith and reason and all that jazz? Certainly. And, most importantly, it will be satisfying. Because that’s what I want out of my television shows: satisfaction. Life may not be written by a show runner in the sky. It may never give us the answers we’re all looking for. But that’s okay. Because that’s what TV is for.

Next time on Overthinking Lost: Okay, what’s the deal with that Monster? Who are these Others? Where did Walt go? Or my answers to other pressing questions… in season two!

Random “Did You Know?”: Did you know the word for seeing patterns in random, meaningless assortments of things is “apophenia”? The things you learn at Overthinkingit.com!

Thanks everyone, for your excellent comments. It’s what keeps me going! So, please comment away! But, remember, no spoilers after season one! I’ve already had one terrible, awful, no good, very bad spoiler this week. I don’t think I can take any more.