For years, Alan Moore (the writer of Watchmen) has been saying that his comics are unfilmable. He has a beef with Hollywood that is easy to understand, especially if you’ve seen the god-awful adaptations of his League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and From Hell. In the late 80s, Terry Gilliam approached Moore, thinking he’d direct the Watchmen film. Instead, Moore told Gilliam that it was an impossible task, like finding the Holy Grail or filming Don Quixote. Terry Gilliam agreed. Watchmen was unfilmable.

But is it really?

Comics and Film: A Comparison

“If you approach comics as a poor relation to film, you are left with a movie that does not move, has no soundtrack and lacks the benefit of having a recognizable movie star in the lead role.”

-Alan Moore

Comics and movies aren’t the same. It’s easy enough to say, but I sometimes get the feeling that most comics writers don’t get it. People working in the film industry definitely don’t; they often explicitly say they use comics as storyboards for their films.

But they aren’t the same. Because Alan Moore is one of the few comics artists who realizes that, his comics will necessarily be harder to translate to film. Here’s a breakdown of what each medium can and can’t do well. I think it’ll give everyone an idea of why Watchmen is a tough piece to tackle.

Time in film.

Time in film is tricky, which is why, I expect, most films occur in order. The beginning’s at the beginning, the middle’s in the middle, the end’s at the end. Obviously, not all films work this way. Some of the best movies of all time don’t: Citizen Kane, It’s a Wonderful Life, Casablanca, Pulp Fiction.

But it’s a lot harder to pull off. Usually, you have to do it in flashback: a character says something about the past, he puts on that faraway drugged out look, and – cue harps and smoke machines – we’re back in the past with them. It’s weird, actually. Most of the film we were watching the characters objectively; now, we’re in someone’s head, thinking along with them, but still watching them from afar.

Tarantino doesn’t use flashback as much – in fact, god help you if you say he uses flashback in his films at all. Rather, he uses chapter headings to separate one period of time from another so viewers know where they are. Woody Allen movies use a narrator, making them more like novels. Some movies have dates written at the bottom of the screen. Harry Potter movies use a nifty contraption called a Pensieve, which is made out of flashbacks. These are obvious ways of letting a viewer know when they are. Unless a director is very explicit, a viewer can easily get lost in the timeline. And if a viewer gets confused about where she is in the timeline, she can’t go back and reread the movie. The movie goes on, whether the viewer gets it or not.

Long gaps in time must be avoided in films, too. Otherwise, you need to put your thirty-year-old hot starlet in plastic wrinkles and a grey wig. It doesn’t usually work too well.

Time in comics.

Comics can handle time better than movies but less well than novels. Artists can draw characters whatever age they want and can put any props they want in the background of scene. It’ll take some research, sure, but it’s cheap and not too hard.

Although comics can jump around in time, because of their visual nature they work more like movies. Unlike a novelist, a comics author can’t jump back and forth between centuries within the same sentence. A novelist could just write, “During World War II, he was a soldier, but now he was just a dentist.” A comics artist would have to draw two panels: one with a soldier, and one with a dentist.

But comics authors can jump around more frequently than a film director. Even the most artsy indie film can only jump around the timeline maybe forty times. If the movie jumped more than once every few minutes, the audience would go CRAZY. And the director would, too.

But, theoretically, a comics author could jump to a new time period every panel. In fact, the Dr. Manhattan chapter of Watchmen (for the most part) does just that. And that is cool. Plus, if a reader gets confused, he can always flip back a few pages and reread. As in a novel, time moves only as quickly as the reader does.

Dr. Manhattan makes time... complicated.

The senses in movies.

Movies win this round due to the realism of their visuals and their use of music. Why do people always clamor for film adaptations of their favorite novels or comics? I think it’s because they want to see their favorite characters and scenes come to life. Comics wouldn’t do it. People want the realism. They want to see the movement.

And music. Because of music (or lack thereof, as in No Country for Old Men), a movie can make an audience feel anything. This can be seen either as a very good thing or a very bad thing. Alan Moore would probably say that music was another way for directors to spoon-feed their audiences and force them to feel whatever they want them to feel at the time. As for me, I think music is amazing – the number one reason movies are better than any other art form.

The senses in comics.

Comics win due to detail. Comics don’t have music, and you can’t smell or taste or feel them.

In terms of visuals, though, comics get the best of the novel and film worlds. Like movies, comics can tell

Page five of Watchmen

a story MUCH more quickly than a novel by using visuals. One panel, like one second of film, can get across a huge amount of information to a reader. Imagine reading that amount of information in a novel:

“Underneath a large full moon in Manhattan stood a turn of the century skyscraper. A man at its base looked up at it. He wore a hat that looked kind of like a fedora and was brown, but not too dark brown, just regular hat brown. The hat had a thick purple ribbon around its rim – but not a garish purple. A dull purple. He wore an old-fashioned trench coat, same brown color as the hat, draped in shadow. Striped pants – zoot-suit-ish – and purple gloves to match the hat ribbon. In his hand, he clasped something, and, around him green papers swirled in the wind.”

That is my description of one panel of Watchmen. One very uneventful panel. (It’s the middle one on page 5 if anyone cares.) On almost every page of Watchmen, there are nine panels. There are about 385 pages in Watchmen, meaning that you would have to multiply that boring paragraph times 3465 to get close to what a novelization of Watchmen would look like. If you double space that paragraph and put it into Courier New, that paragraph is almost half a page of novel text. At this rate, that means the novelization of Watchmen would be at least 1700 pages long to get in that amount of information. That’s the number one difference between a comic and a novel.

A movie could have that same amount of detail, but a viewer couldn’t appreciate it as well. Movies, as said before, move. A viewer can’t linger on a frame and appreciate every detail in it, unless he is watching it on

Jimmy Corrigan: Unfilmable

DVD. (Who else but Roger Ebert actually does this, though?) That’s why comics can include maps (see Hicksville and Fun Home), mechanical diagrams (see Jimmy Corrigan), and intricate cityscapes (see anything by Joe Sacco), and movies can’t.

Even if you did want to write a 1700 page novelization of Watchmen, you STILL couldn’t get across all the information. Novels can’t deal with issues of space and composition. Movies can, sort of, but today scenes are cut so fast that viewers don’t have that much time to pay attention to that stuff. Anyway, in a novel or a film, the cleverness of Chapter Five, Fearful Symmetry, for example, would be lost. Chapter Five – and you might not have noticed even if you read the comic – is completely symmetrical. All twenty-nine pages of it. You couldn’t do that in a novel. You couldn’t even do that in a movie. That’s something only a comic can do.

Scope in comics.

Comics, theoretically, can be as long as an author wants. You can write series. You can spend your whole life developing backstories. You can have spinoffs. You can wring every last drop of juice from your premise if you want.

Scope in movies.

If you are a film director, you have between 90 minutes and 120 minutes to tell your story. If you are particularly lucky, you may have up to 160 minutes. If you are super lucky, you are Peter Jackson and you got to do three three-hour long movies.

In other words, you can have good character development but few characters, or many characters but little to no character development. Your choice. Don’t expect your themes to be particularly deep. You don’t have time to develop them.

So is Watchmen filmable or what?!

My answer is “yes, but…” Is Watchmen filmable? Yes, but it’s going to lose a lot. I don’t care how careful the director, Zack Snyder, claims he is trying to be. Any transition to film is going to be rough. As I showed above, just because comics are visual, it does not mean that they are easier to adapt to film than novels.

So what’s Watchmen going to lose?

Its visual detail: I’m sure we’ll see smiley faces in the background of certain scenes, but that’s about it. We simply won’t be given the time to analyze the contents or compositions of each frame. Movies don’t allow that.

Some character development: Dr. Manhattan will keep his since his backstory is vital to the events in the story-story. I expect Rorschach will get some development since everyone seems to like him so much. Unfortunately, the Sally-Laurie subplot might get condensed or even axed, which is sad because it was easily the most human story in the book. Nite Owl the First will, I predict, get no history. The psychiatrist and his wife will be cut. The Laurie-Dan subplot will get play (can’t have a movie without a love story!), but I expect it will be less complex than the original due to time constraints.

The “books within books.” While I can’t fault the filmmakers for getting rid of the pirate comic book, the academic texts on superhero politics and bird watching, or Ozymandias’ internal memos about his product line, I’ll be sad to see them go. They’re what gave the comic texture. The film is going to be sleek and easy like all Hollywood products, not bursting at the seams like the comic. Films just can’t have that amount of layering.

The intertextuality. I’ll eat my hat if the movie uses the quotations the comic used. Except for “who watches the watchmen.” Someone will say that, or at least it’ll be somewhere in the background. Otherwise people will leave the movie saying, “But why was it called ‘Watchmen’? Weren’t they called the Minutemen?”

That’s not all the movie will lose, probably, but those are the things that the film will necessarily lack, due to its form. Due to Hollywood meddling, we also might see less moral ambiguity, although if they make Rorschach into a hero I might start laughing in the theater.

But the trailer doesn’t suggest that. I do think Mr. Snyder wants to make a relatively faithful film. As long as he keeps that dark, foreboding mood, then he’ll get as close as he can.

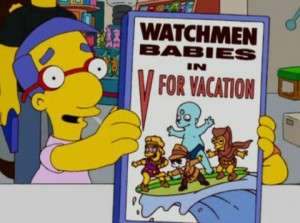

A slightly less dark version of Watchmen

***

As a gift for reading through this long, unfunny article, you get to watch the Watchmen trailer! Enjoy.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E4blSrZvPhU