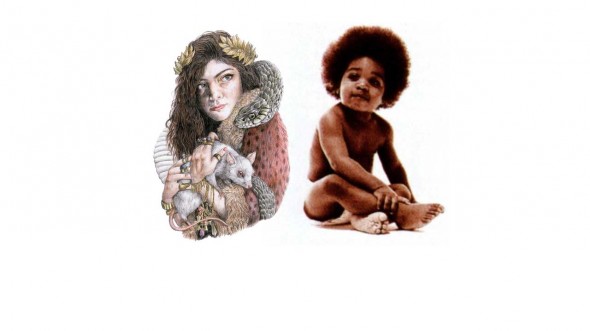

Racist?

Over the past few weeks, Feministing blogger Veronica Bayetti Flores has written posts that identify racist undertones in both Lorde’s Billboard-topping song Royals and the critical discourse surrounding the song.

The brief summary of Flores’s argument is that critics have lauded Royals as a critique of consumerism, but that that many of the luxury brands that Lorde lists in the songs chorus are associated with contemporary hip hop, which makes her critique of conspicuous consumption highly problematic because of the racial associations of what she is criticizing. The post has been covered in articles in mainstream media outlets, and has prompted counter-arguments from many commentators.

Despite the high volume of publication on both sides, the debate has made little progress over the past two weeks, leading one columnist to conclude, “No, Lorde’s Royals is not racist. Can we dial back the lyric parsing?”

Dial back? We have not yet begun to parse.

For me, what is most frustrating about the Royals debate is that both sides assume that the song should be interpreted at the macro-level. That is, both Lorde’s supporters and detractors tend to assume that the song’s lyrics (most notably the laundry list of luxury brands in the chorus) are focused on big picture concepts of class and race.

In contrast, I tend to interpret the song at the micro-level. When I hear Lorde say that “everybody” is always talking about “Cristal, Maybach, diamonds on your timepiece”, I actually suspect she’s referring to other teenagers in her suburban Auckland high school, rather than the hip hop stars who are her new neighbors on the billboard charts. When Lorde talks about “postcode envy” and counting on money on the way to parties, she’s focusing on her anxieties about her socio-economic status vis-a-vis her peers. This interpretation helps to explain why the chorus of Royals combines brands associated with hip hop with more incongruous images such as “ball gowns” and “trashin’ the hotel room”. In the context of this song, Lorde’s engagement contemporary hip hop is mediated by the cultural appropriation, social posturing, and bad behavior of the rich kids in her hometown, in the style of the Rich Kids of Instagram and Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring.

As I discussed in the recent TFT podcast on Royals, this is similar to my own experiences in high school. In my upper-middle class suburban Pennsylvania school district, what music you liked was very closely linked to socio-economic status. In my memory, the biggest fans of hip hop in my high school were the “cool kids”—the children of the doctors and lawyers who were at the top of the social pecking order. In my limited glimpses of their parties, they recreated and appropriated that era’s version of hip hop conspicuous consumption, with gestures toward the Benzes and Cristal associated with mid-90s commercial rap. Although I was largely excluded from these social circles, I do have distinct memories of awkwardly dancing to the Notorious B.I.G.’s Big Poppa at a 16th birthday party at my hometown’s fancy country club.

Given my association of Big Poppa with the micro-dynamics of high school depicted in Royals, I decided to create a mash-up of the two songs:

Although Biggie lists a number of trappings of luxury (Moet, c-notes, mansions, jacuzzis), he also lists off the ingredients for a much less flashy midnight snack (T-bone steak, cheese, eggs, and Welch’s grape), and elements of the drug trade (measuring grams of cocaine, gats with laser beams). As in many of Biggie’s songs, this juxtaposition of images associated with both extreme wealth and extreme poverty situates his path to wealth within the everyday struggle that preceded his rap career.

What the mashup reveals is that both Royals and Big Poppa both circle around ideas about engaging with inequality in one’s own social circles (in New Zealand and Brooklyn, respectively) as the basis for art, and then using that art as the foothold for social mobility. Lorde’s background is very different from Biggie’s, but it is more useful to see her engagement with contemporary hip hop through this lens, rather than as a “critique of consumerism,” even though this reading is promulgated by her record label’s PR team symbiotically with the media hype machine.

As Lorde’s career unfolds, I’m curious to see whether or not she will be able to use her unique artistic perspective to push back on the dominant discourse and use her relative privilege and newfound fame to not just make herself the “Queen Bee”, but to shake up the whole hive.