Shrewd investor.

Pop culture steals from us some of our object permanence. Like a baby playing peek-a-boo, when we don’t see a celebrity or pop culture icon for a while, we have a tendency to assume it no longer exists.

Knowing that something keeps existing when we can’t perceive it, that’s object permanence. But, like that same baby playing peek-a-boo, we often squeal in joyful recognition a the object’s return, whether the object is worth the celebration or not.

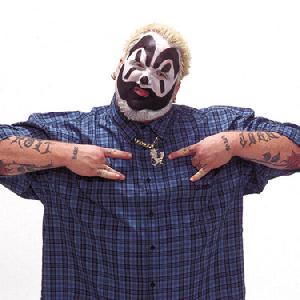

A baby can be happy just to see your face again after you uncover it. Hardly a remarkable thing. And we at Overthinking It (or at least this guy at OTI), can be happy to see the return to the public eye of turn-of-the-millennium horror rap superstars the Insane Clown Posse (ICP). You know, whether we ever liked them in the first place or not.

It’s been a while coming, and you may have already seen this, but this video is where I got back on board with Insane Clown Posse after a decade of assuming they no longer existed:

I’ll get to this video in a bit, but first we must ask – ICP were a novelty act with a sound that ranged from hard rock to old school rap (as in, they sounded like early 90s rappers in the late 90s) that was popular in the mainstream and sold a few million records about a decade ago.

Why are they still around? How did they survive as an institution in what can be kindly termed “relative obscurity?” How is it that they have continued to produce relatively successful albums independently after leaving stardom? How is it right now that they seem to be getting more attention in pop culture circles than their Detroit rap contemporary and arch-rival Eminem, even if the rivalry seems so utterly laughable now?

The answer is one remarkable word – and it’s a word that teaches us pretty much everything we need to know about how the market, politics, social capital, power and control work in contemporary society – because everybody is trying to do this, and most of those people trying don’t tend to do it as well as ICP.

That word is “juggalo.” And juggalos are the new gold standard. The fact is, today’s is a juggalo world, and we’re all just living in it. Read on …

Obligatory fiery clown thing.

The Basics of Juggalos

The most basic and important thing to know about juggalos is that people at large tend not to like them very much, respect them very much, or be very nice to them. So, they self-identify as a group of outcasts, and like many groups of outcasts, they follow charismatic leaders and have developed their own iconography, phantasmagoria, mysticism, personal customs, national costume and slang. A lot of this centers around how they are welcomed by the Insane Clown Posse and company, even if they’re not welcomed by anybody else. This, in turn, marks them further as outcasts, reinforcing how different they are drawing them closer to each other.

Oh, the second most basic thing to know about juggalos is that they are fans of Insane Clown Posse or any number of other connected groups on the Psychopathic Records label, who are generally similar in musical style, the wearing of clown face paint, and a bunch of other stuff (for examples, they have a tradition of spraying a cheap brand of Midwestern soda called Faygo on each other). “Juggalos” is derived from the ICP song “The Juggla,” and it doesn’t really mean anything prior to its nonce use to describe fans of Insane Clown Posse and their record label – particularly those who buy in to all the aesthetic trimmings.

The third most basic thing to know about juggalos is that they are generally thought of as young. It’s a group that was put together for a lot of disaffected teenagers. That’s why they have things like helicopter rides and Ferris wheels at their music festivals.

The fourth most basic thing to know about juggalos is that the culture has a lot of anger directed at people who invoke prejudice or marginalize people. A bunch of the songs refer to murdering bigots and similar revenge fantasies.

So, what, these second, third and fourth things don’t seem so bad. Why are they mocked so much? Well, it’s kind of a self-selecting group. It’s my take that it is more likely that people become juggalos because they are outcasts, not that they are outcasts because they are juggalos, even though that’s what the YouTube comments would lead you to think.

Juggalos have been getting a lot of attention lately, because, true to the convention of people making fun of juggalos, Saturday Night Live has made some pretty successful sketches mocking them. There’s this parody video of the video I posted earlier:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yi08uLTOGxs

And then there’s the original video that kicked this off, the infomercial for the 2009 Gathering of the Juggalos (a big juggalo music-and-other-things festival in the middle of nowhere). Saturday night live made a parody of this infomercial, which was an online success. Here’s the infomercial:

And here’s the SNL parody:

Oh, and for good measure, here’s a more typical Insane Clown Posse video from 1997 (which gives you a sense for why the new ICP song seems out-of-place):

It’s easy to make fun of ICP for being stupid, ignorant or for making bad recommendations for life. Heck, it’s easy to do that for a lot of folks – doesn’t mean it’s right. There are three important things to keep in mind that, by my estimation, take the gas out of that argument:

- They are wearing clown makeup and acting all crazy in a fantastical way. Even when they are not being “ironic” in the hipsterish sense of the word (to which I give less and less credence – I tend to think of it nowadays more in terms of rationalization than true intellectual detachment nine times out of tem), they understand and reflect that they are crazy. In other words, it’s hard to imagine anybody trying to tell you any harder that you shouldn’t take them seriously.

- By holding up ICP to a standard of intelligence, or good judgement – or really, most importantly, worldliness – you hold them to a higher standard than other popular musicians are ever held. Tupac recommends you do a lot of stupid stuff in his songs, too – stuff you probably shouldn’t do in real life. Notorious B.I.G.’s obsession with even minor articles of luxury is laughable (“Super Nintendo, Sega Genesis / When I was dead broke, man, I couldn’t picture this!”). There’s an argument about higher or lower levels of stupid, but I think the “don’t try this at home” disclaimer applies. Also, there are a number of race issues here, but I won’t tackle that in this segment.

- ICP is the music of the people making it and listening to it. It should not be surprising that, in America today, there is music that expresses suspicion and mistrust of scientists. To people who are incredulous that this could even exist, I’d say open up your eyes and look at the world we live in. It’s easy to dismiss people you don’t agree with or give credence to, but — again with the object permanence — ignoring them does not make them go away, and maybe we can learn something from their culture. I’m a big fan of paying attention to writers whose messages you don’t agree with. Otherwise, I could hardly justify reading Dante. Prioritizing political responsibility as the chief value for literature and music is a great way to dull your mind to the greater human experience and artistic project.

Still, it’s also important to note than ICP isn’t really all that great of a rap group. Shaggy 2 Dope is a much better rapper than Violent J, and they both could probably make some better music if they branched out a bit more. They excel on their charm, showmanship, persistence and gimmicks – and because of a social creativity on a level above their musical creativity that has created this unique fanbase.

From each according to his work, to each according to his giant money bin.

Theories of value

With that background taken care of, let’s talk about theories of value. A small disclaimer here: I generally limit my discussion of this topic because of the desire to separate my IRL, for-a-living job from my OTI work, so there are certain topics I’ll stay away from or not belabor, because they may be sensitive related to my work. Feel free to address them in the comments if you want, but if I don’t respond, that’s why.

A lot of the outrage surrounding the recent financial crisis has involved the notion that finance involves “things that aren’t worth anything,” or a lack of “intrinsic value.” As in, people who are making exotic financial instruments shouldn’t do so — instead, they should make, say, spoons or pants or fish food, because these latter things have intrinsic value, while financial products do not.

Of course, this is the same logic that led people to think that houses were foolproof investments (because they are “actually worth something,” because people live in them) — and we all saw how that worked out.

The sad fact is that, at least when it comes to exchange or “money” – nothing has intrinsic value. We learn from the King Midas tale or the Ice 9-but-with-gold episode of Duck Tales that there are circumstances in which gold is not only worthless, its presence is a horrible problem. So gold doesn’t have “intrinsic value” – it’s worth a lot less to King Midas or Scrooge McDuck in that episode where the world turns to gold than it would be worth to me right now.

And currency doesn’t have “intrinsic value.” Right now, a lot of places in the world, including the United States, use a system of “fiat money” – that is, the money is only money because the government says it is money, and its main guarantee of value is the full faith and credit of the government that says it has value and the declaration that it is legal tender to pay debts.

This seems like it is less “intrinsic” than gold, but really it isn’t – not because fiat money has intrinsic value, but because nothing else does either. When you’re talking about exchanging stuff for other stuff, something, anything, is only worth what somebody else will trade you for it. No matter whether it’s fungible or not, guaranteed or not, “usable,” has a long shelf life, is animal, vegetable, mineral — when it comes to economic value, stuff is just stuff, and it is worth what people will give you for it.

This should be good news, of course. It means that money isn’t really that important, and stuff isn’t really that important. That any kind of money at all is to some degree an illusion — an important one, and one that has impacts on people, but an illusion nonetheless. If you, like me, love culture and art, you’ve probably figured this out already — money is important, sure, but it’s not that important. So, you let that warm your heart and use it as consolation during your long subway rides to and from the office in the grind to get more of it.

However, if you’re the sort of person fascinated by the interaction of goods and services with people’s lives — somebody who thinks that this interchange of money and things-acting-as-money really is essential to the human condition and one of the most important things going on. If you’re, say, Adam Smith or Karl Marx, you look for a way to thread this intellectual needle. One way economists have done this is the Labor Theory of Value.

There are a lot of variations on the Labor Theory of Value, but the basics of it is that people’s work is the “intrinsic value” in something — that money is worth how hard it is to make money – and to make the things that make money. So, the laborers who produce commodities and other things of value up and down the supply chain that make the whole bus roll down that big economic road of life are the reason stuff is worth stuff.

I tend to see the process as more cyclical — and to subscribe to a more subjective theory of value myself, as I’ve said. The argument usually goes something like this.

“Okay, these shoes have value because people make them.”

“Well, what if a robot makes them?”

“Then the shoes have the value of the labor used to make the robot.”

“But what if the people who made the robot need sandwiches to work?”

“Then the value of the robot depends on the value of the labor used to make the sandwiches.”

“But the people making the sandwiches can’t make them without shoes.”

“Well, the value of the shoes is the value of the labor used to make the shoes.”

Yeah, you can say interesting things up and down the manufacturing, distribution and supply chains about all the people working, but you end up with a “‘There’s a Hole In the Bucket, Dear Liza, Dear Liza’ Theory of Value:”

So, where does this leave us?

We get to choose where in the various cycles to focus our energy. We can try to make better shoes, we can try to make better robots, we can try to make better sandwiches. Each of these is going to have different effects. Sometimes you want to be the person making shoes. Sometimes you want to be the person making robots. It changes with history and the seasons.

Sometimes you want to be the person making juggalos.

Juggalos vs. Albums

Here we get to my main point in this first part of this post on juggalos — ICP was a popular music act in the late 90s and early aughts that was selling a lot of albums. Over the last decade, they could have tried a bunch of different ways to sell records. They could have ditched the face makeup. They could have spread the field a bit more with their genre selection.

But they didn’t. Instead, they invested in their fans. They built up a stable of acts that would appeal to their fans, they built up a social infrastructure, formally or informally, around their fanbase, and they started and built up their “Gathering of the Juggalos” music festival to the point where its attendance has grown a lot and it’s starting to get people to notice.

And, like the shoes and robots, focusing on the juggalos has led to them getting more attention, which leads to more fame and more albums and more “success,” however you choose to define that as a musical group, presuming you define that in some external terms at some point (which you don’t necessarily have to, of course).

It might have seemed dumb to focus on a bunch of outcast teenagers and what they want over a decade rather than ditching your tired novelty act to sell albums. But look what has happened to album sales across the industry, relative to growth of the Gathering of the juggalos over the last decade:

The main point is that if you are an act that has focused on selling albums for the past decade, the trends in the industry have got to have you shitting your pants right now. Even including album downloads and singles, the revenue in the recording industry is collapsing.

But, if you focused on juggalos, you’re in a boom time. You have potential for growth, and that means you have the potential to make exciting things happen, like big music festivals with helicopter rides and Rowdy Roddy Piper doing stand-up.

Granted, there’s a lot more albums than juggalos, and a lot more money in albums than in juggalos, but when you’re looking at economics from the perspective of somebody taking action, it’s the movement that’s important — where are things going? What is going to matter more in the future relative to how much it matters now? What is going to be worth more? What is good to invest in?

The numbers say that, over the decade, juggalos have been a pretty good investment, and that ICP is on to something.

In part 2, we’re talk about the broader applications of this idea, and what it means for economics, business and politics.