The Ship of Theseus Paradox is a philosophical conundrum about identity and change that goes back to the Ancient Greek writer Plutarch. He related a scenario regarding the ship on which the mythical Theseus sailed from Crete back to Athens, the city that he founded. According to Plutarch’s account, the ship itself was preserved for its historical significance, but over the years as it fell apart and decayed with age, pieces of it were replaced – a plank here, a…I don’t know…a stern there (a stern is a thing that ships have, right? I’m pretty sure most ships have a stern) – until, eventually, there was nothing original left. Every part of the ship was “new,” in that there was no longer even a single board that had been in the ship at the time Theseus had sailed on it.

Is it the same ship or not? Given that it’s a completely different constellation of materials, does it matter that its parts were replaced only gradually? Is there a real sense in which we can say that, yes, this is the Ship of Theseus, even though it’s a completely different constellation of materials, sharing no components with the vessel on which Theseus sailed?

Plutarch tells us that the philosophers were pretty much evenly split when it comes to their intuitions about the Ship of Theseus. Over the millennia since he first elucidated the paradox, philosophers have struggled with trying to resolve it, and their beliefs on the subject have more or less stayed the way Plutarch described them: some say yes, some say no.

But here, today, on this very website, I am here to report: don’t worry, you guys. I’ve totally got this. That’s right, ladies and gentlemen, I have resolved the Ship of Theseus Paradox once and for all, and as soon as this article goes live I can categorically guarantee that no man, woman, or child will ever have to worry about it for the remainder of humanity’s existence in this physical realm. The Ship of Theseus Paradox is over and you can finally get on with your life. You’re welcome.

Oh, right, I should probably tell you the solution.

Okay, so I was thinking about hockey. As a Canadian this is a legal obligation to maintain citizenship. Our Prime Minister – and this is not a joke – even wrote a book about the history of the sport. And as a fan of the Toronto Maple Leafs, thinking about hockey mostly just makes me sad. If you’re not familiar with the National Hockey League, suffice it to say that the Leafs are not only the most profitable team in the NHL and number 31 of the 50 most valuable sports franchises in the world, but they are also an organization acclaimed in the annals of professional hockey for finding new and exciting ways to lose, spectacularly annihilating the perennial hopes of its infinitely forbearing devotees every single year. Being a Leafs fan is a lot like being in a relationship with someone you know is really bad for you: they keep saying that they’ll change, and you keep believing them.

Wayne Gretzky, I know you are the greatest hockey player of all time, but I will never forgive you for this.

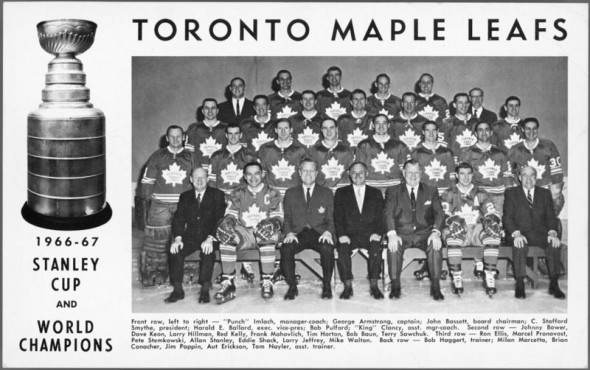

And but here’s the thing: they have changed. Since the formation of the NHL in 1917, the team now known as the Maple Leafs have won 13 Stanley Cup Championships, second only to the damned Montreal Canadiens who have 23. All of those Stanley Cups, though, were won prior to 1968. Toronto has not won a championship or even made the finals since winning in 1967. The team went from consistent contenders to predictable losers overnight, and have stayed that way – and this is the part that’s relevant to the topic at hand – despite the fact that the composition of the team is completely different than it was in 1968.

They have had good seasons and bad seasons, but they’re always the same Leafs. The 2012/13 season is the perfect example of that: after making the playoffs for the first time since 2004, the Leafs faced the Boston Bruins in the first round; they managed to roar back from a 3-1 deficit in the best-of-seven series to force game 7, were up three goals to one going into the third period, and then totally and catastrophically collapsed, letting in three goals to tie it up before losing in overtime. The entire Leafs Nation felt like we’d been sucker punched. Not just because we lost, but because this was exactly what we should have expected.

No matter how many times the team reinvents itself, it is still the same team. Every player, coach, manager, trainer, and scout, is periodically replaced, one by one, until there is no similarity in the makeup of the team to what it was at an earlier time. But just watching them year after year, that they are the same team is readily apparent – which makes absolutely no sense. Just like a person whose cells all die and are replaced over years and decades and yet someone, we insist, remains the same person.

This realization led me to understand that the professional sports team is our age’s Ship of Theseus. And we can use that to do philosophy. We can look at the Toronto Maple Leafs to consider the Ship of Theseus Paradox from a different perspective, and maybe discover some truths about identity and change that have gone heretofore unconsidered.

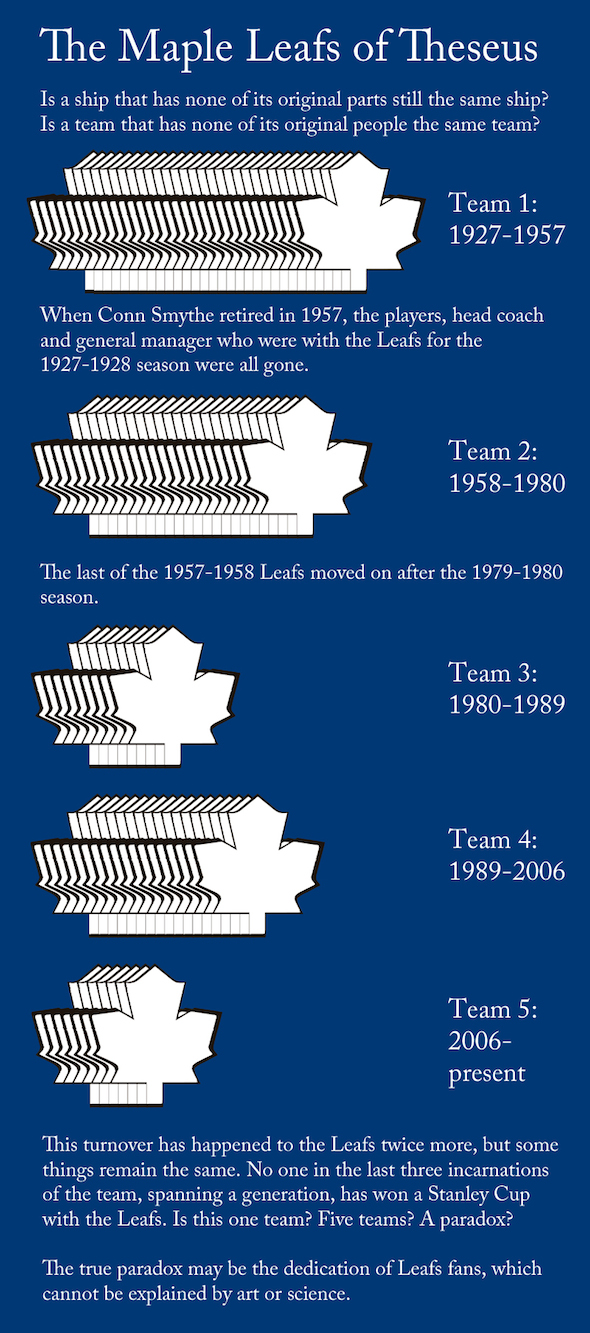

Numbers crunched by Mark Lee. Awesome graphic by Peter Fenzel.

So let’s take a look here. As we can see, between 1927 and 2013 there have so far been five complete roster turnovers (Official Pastry of the National Hockey League). The first question this raises is: is this actually the same team or not? Is that chart an actual representation of the evolution of something, or are we imagining continuity when what we’re dealing with is just a bunch of discrete items temporarily associated with one another? My intuition is that, yes, “The Toronto Maple Leafs” is a real thing, and despite the fact that none of its constituent pieces remain from when they became the Maple Leafs in 1927 (before that they were called the Toronto St. Patricks, and before that, the Toronto Arenas – in case you thought that “Maple Leafs” was a dumb name, you don’t know how lucky we actually are these days) – and in fact that there’s nothing left of the Maple Leafs of only seven years ago – somehow it’s still the same team.

What does that mean? Why do I (and obviously most of sports in general is modeled after that notion of continuity) feel that there’s something that persists across the decades even though there isn’t really anything that’s actually persisted?

But that’s not actually true, is it, that nothing has persisted. They are still the Toronto Maple Leafs. Why?

It’s at least in part because they are still called the Toronto Maple Leafs. A name is part of what gives something its identity. When Conn Smythe took control of the team in 1927 and renamed it the Maple Leafs, there really wasn’t any difference between the team before and after the name change, but the name became part of the team anyway. The philosophy of the semantics of names is a complicated issue in and of itself, but suffice it to say that when someone refers to the Toronto Maple Leafs, we know what they’re talking about. We gain more information if they give us a specific year or range of dates, but that roster data is not strictly necessary to convey what’s trying to be communicated by the name “Toronto Maple Leafs.” That is to say, no single player, coach, manager, or particular collection thereof, are essential components of the team such that without them it ceases to be the Maple Leafs. But the name is not the only thing, either, and the players are not incidental to the team’s identity – when ownership changed in 1927 and the name changed to the Maple Leafs from the St. Patricks, but none of the players changed, really it was only the name that changed and not the team in any essential way. What we’re beginning to see is that a name is at least as important as a player – in fact more important than any particular constellation of players – but not more important than the entirety of everything else about the team. My intuition is that, had every single player also been replaced in 1927 when the team’s name changed, it would no longer have been the same team. “Toronto Maple Leafs” is an indexical utterance that points to a specific collection of individual hockey players at a given time, but it also carries part of the weight of identity in itself.

Then again, there are other factors too that are, in some sense, external to the actual composition of a team that nevertheless also carry some of that weight of identity. The Toronto Maple Leafs are based in Toronto. So location is another of those essential characteristics. They also have a distinct fanbase. The Toronto Maple Leafs is the team that is rooted for by anyone who self-describes as a Leafs fan. That also has absolutely nothing to do with who is on the ice at any given time, or even what arena they’re playing in. So collective allegiance is another external factor that contributes to the team’s identity as an entity distinct from others.

To further demonstrate that these things (name, location, and fanbase) are essential characteristics of identity, we can contrast by looking at a team that has lost all of those things in addition to its players: The Winnipeg Jets.

In 1972, the Winnipeg Jets joined the NHL after the rival World Hockey Association, of which it was originally a member, folded. They operated in Winnipeg until 1996; the small population of the city relative to most NHL markets, combined with the effect of the weak Canadian dollar (all NHL player contracts are in U.S. currency, but income for Canadian teams is, of course, in Canadian currency, putting Canadian teams at an economic disadvantage when the exchange rate fluctuates) had made the team unprofitable. The owner of the Jets sold them, and the new owner moved the team to Arizona, renaming them the Phoenix Coyotes.

We missed you guys.

Now, the team’s location and name had both changed, but all the players remained the same. Was the 1997 Phoenix Coyotes the same team as the 1996 Winnipeg Jets? This seems like a much more difficult question to answer intuitively than our previous question about the Maple Leafs. I don’t know how many Jets fans became Coyotes fans, but I suspect it’s not many – almost certainly not a critical mass of them, anyway. What it looks like, then, is that player composition is a much less sufficient factor for continuity of identity than team name, location, and fanbase. The Phoenix Coyotes have less claim to be heir to the identity of the Winnipeg Jets even when all their players are the same than the Toronto Maple Leafs have to their identity even when all their players are different.

Further reinforcing that point is the fact that in 2011, Winnipeg got their team back. The city’s population had grown, making it a much larger market than it had been, and the Canadian dollar was now much closer to parity with the U.S. dollar, making it more economically feasible for a team to operate there. The embattled Atlanta Thrashers moved to Winnipeg and were renamed the Jets! After 15 years, Winnipeg has its Jets back – but does it really? Is the team that’s currently playing under the name The Winnipeg Jets in any way the same team as the one that departed in 1996 and may or may not be still playing under the name the Phoenix Coyotes? No, and yet kind of yes. Because look, either way it’s unlikely that there would be any players, coaches, or managers in common between 1996 and now even if the Jets had stayed put in the first place. But we’ve already seen that that doesn’t really matter, or at least that it’s not the only factor, or even a major factor in what determines the team’s identity. Both teams play in Winnipeg, both teams are called The Jets, and both teams share the same fanbase (more or less). Meaning that there is pretty much no difference between the current actual Winnipeg Jets and what would have been the current Winnipeg Jets in a universe where they’d never moved to Phoenix. For all intents and purposes, ontologically there’s no way you can say that they are not the real Jets, even though their compositional continuity is completely broken.

The same thing applies to the Maple Leafs (and every other team, obviously). How can they be the same team even though every player is different? The same way that you are the same person even though you share zero cells in common with yourself at birth. The same way that the Ship of Theseus really is still the Ship of Theseus even without a single board remaining from the ship on which Theseus sailed. Because there are necessary metaphysical factors that are collectively more important contributors to the object’s identity than its physical composition. The physical composition is, in fact, kind of arbitrary. The 1927 Toronto Maple Leafs could have been anyone and still been the Leafs. But they couldn’t have been based in, say, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Having a certain name, being in a certain place at a certain time, and being in a certain type of relationship with a number of other individuals who self-associate with that name, place, and a configuration of parts (but not any specific configuration in particular) is what creates identity. Physical continuity contributes, but is not and cannot be the make-or-break factor in determining identity.

This is a modification of Leibniz’s Law, or the Principle of the Identity of Indiscernibles, which states that two objects are identical if and only if they share all the same properties and relations. Obviously the 2013 Maple Leafs don’t share all the same properties and relations as the 1927 Maple Leafs. But they do share all the essential properties and relations, some of which are themselves built of up smaller inessential properties.

The Ship of Theseus, then, is not, and cannot be, just the sum of its parts. Its identity is part physical, part historical, part semantic/referential (which it itself a gigantic problem in philosophy because we don’t really know what names are, but for the purposes of this argument, we know a name when we see it and we know what it does and what it points to), and in part just a tiny piece of an immensely complicated web of relations that needn’t be physical or even directly causal in any way.

There’s something weirdly mystical about that realization. On the ice, when today’s Leafs look disturbingly similar to the Leafs of 1995, there’s a reason for it. When we can’t understand how it’s possible that they haven’t won a Stanley Cup since 1967, it’s not a senseless thought. The Toronto Maple Leafs has a soul that transcends its physical body or bodies. Part of that soul certainly exists inside every player, past and present, who has been part of the organization. But part of the soul exists in the city itself, and part in the weird Platonic realm where names live. I guess what I’m trying to say is that we are all Horcruxes; that part of that soul, of the transcendent identity that makes the Leafs the Leafs (and makes other teams whatever they are too, I guess) is also inside every long-suffering fan. Which explains why watching the Leafs lose season after season hurts so much. It’s not just happening to them. It’s happening to us too. The Toronto Maple Leafs is the thing that makes Leafs fan cheer when they win, and cry when they lose.

So when the Houston Oilers move to Tennessee, become the Tennessee Titans, and then Houston gets a new team (the Houston Texans)….

Are the Texans the Oilers? Or are they just plain Texans? Is it all in the name?

Lots of Houstonians are oilers (work in the Energy industry), but not all oilers are Houstonians.

Are the Tenneseeians Titans or are they Oilers?

/mind blown/

But….The big question still remains… WTF is up with the Astros? (or as we call them Lastros)

Falconer

(a Houstonian)

Oh yeah, I forgot the most important part…. after the Oilers became the Titans they went and won the Super Bowl.

A feat the Texans have never even dreamed of…

not that I’m bitter.

Well, actually, they came a yard short of winning the Super Bowl. Which could be a fate worse than getting to the Super Bowl by some standards.

First off, wow. This turned out every bit as awesome as I hoped it would when we were working on this.

Second, I wanted to bring up in the comments something we talked about when putting this together: if you think about continuity for either a sports team or the Ship of Theseus from a slightly different perspective, it’s actually quite easy to trace the current version back to the original.

Right now there’s a Leaf player who played with someone who played with someone who played with someone who played with someone…etc etc who was on the original roster. Likewise, with the Ship of Theseus, each new piece coexisted with a piece that coexisted with a piece that coexisted with a piece…etc etc of the original ship.

Using this logic, the new Winnipeg Jets are not the same as the old Winnipeg Jets.

And on a related note, as a longtime (but not quite as intense as I used to be) hockey fan, I am embarrassed to say that I only now learned that the Atlanta Thrashers moved to Winnipeg and were reborn as the Jets.

But what about trading players? I know next to nothing about hockey, but assuming it’s comparable to baseball, couldn’t you also draw the same lines amongst players from different teams? And are there no players on New Jets who played with a player who played with a player…. who could be traced to the original Jets before being traded?

As an Australian, all this “hockey” stuff just went right over my head.

Nonetheless, I think I agree with what you’ve said about sports teams… which ironically brings us, as I see it, to the opposite conclusion about the actual Ship of Theseus. The important part is having all the same essential properties and relations, yes. But the Ship has value for its historical significance: it’s the Ship *of Theseus*, the one which Theseus sailed and Theseus touched and on which Theseus slew monsters and whatever. It is only important for its connection to Theseus, not for the fact that there is a museum exhibit called ‘The Ship of Theseus’ or anything else. As you said, the Winnipeg Jets of 1996 and 2011 are really the same team… but the 1997 Phoenix Coyotes were not, because they had lost essential relationships to fanbase and city. Once the Ship is fully replaced, it loses its essential relationship to Theseus; it’s now just a patchwork ship.

This could, of course, be different if the Ship were significant for something other than history. If it were some sort of protective talisman for Athens, or was used in an specific religious ceremony, or a boat race, or whatever… then the relationship with the ceremony (or whatever) might well override the lack of a relationship with Theseus.

Corporations are fundamentally a Ship of Theseus solution to a business problem. Since sports teams are incorporated business entities, I think that their continuity issues are solved as a subset of that solution. Aside from possible issues tracing lineage through restructuring, this has the benefit of being quite objective.

“Since the formation of the NHL in 1917, the team now known as the Maple Leafs have won 13 Stanley Cup Championships, second only to the damned Montreal Canadians who have 23.”

*cough*

Montreal CanadiEns

*cough*

And I don’t even follow hockey! ;D

Fixed. Thanks, Amanda. I can assure you that this was a spellcheck issue and certainly not an artifact of my obligatory yet genuine hatred of Montreal and their maudit Grand Club de hockey Canadien.

When teams move, it certainly presents issues to those left behind (the Ravens’ first Super Bowl win certainly wasn’t the Browns’ first, but most of the Avalanche were Nordiques), but I can’t follow this analogy much further than that because the alternative to a free flow of players is the MLB reserve clause, and various other variations therein.

I’d hate to be unable to ever leave my job (except by trade?), and so, I imagine, would everyone else. So, yes, as Seinfeld once put it, we root for laundry. But then the players wearing that laundry become endearing, for good or bad reasons, and we don’t care that they were Athletics or Phillies or White Sox last year. And thus, the Ship is still the Ship.

Your citation of the Winnipeg Jets/Arizona Coyotes reminds me of the NFL equivalent: the Cleveland Browns/Baltimore Ravens. The Browns famously left Cleveland at the end of the Nineties, relocating to Baltimore and winning a Super Bowl championship shortly after. Does that mean that the Cleveland Browns won the Super Bowl? (the win this past Super Bowl by the Ravens doesn’t come under the same questioning because the Ravens were at least a decade removed from their Cleveland exit.) Cleveland got a new version of the Browns soon after (can’t recall off the top of my head where they originated, but the reclaimed the name “Browns” and set up shop).

The newborn Cleveland Browns sprung fully formed from the head of Zeus. That is to say, much like the Houston Texans, they were an expansion team. Used their first overall pick on Tim Couch. Good times.

The Browns are the team that most stuck out to me vis a vis this conversation, because while the original franchise moved to Baltimore, the NFL deigned that Cleveland got to keep the Browns’ “history.” So, in essence, as far as the NFL is concerned, the Ravens are more like the expansion team. The Browns are more like a team that missed a couple of years and then returned like nothing happened, even though they were an expansion team. Cosmic, right?

I think this may be the case with the newborn Jets too. Don’t they have old Jets’ jersey numbers retired? Do they keep the old Jets’ history? I do not entirely recall. All I know is that, as far as everybody is concerned, the Thrashers are dead. They are footnote alongside the Cleveland Barons.

In the end, you can all keep your Maple Leafs and Canadiens. Go Wings!

Well the verdict is in.

According to Google the Houston Oilers ARE the Tennessee Titans.

I just ran this experiment: type “Houston Oilers” in any Google search bar and the first hit is “Tennessee Titans”.

Case closed.

Falconer

(A Houstonian)

There was an experiment once about monkeys trained to stay in their sheltered areas when a certain bell rang, because outside the shelter was sprayed with cold water. Gradually, the monkeys went into the shelter when the bell rang, even without the water spray. Then the experimenters started moving a few new monkeys into the experimental group, and moving out the old, trained monkeys. The new monkeys were taught the bell response by the old monkeys. Eventually, the group was completely composed of monkeys who had never experienced the cold water spray, but still moved into the shelter when they heard the bell. The group’s continuity consisted of knowledge (even bad knowledge).

Therefore, a social group like a sports team might retain knowledge (even knowledge that doesn’t do them any good) despite a complete turnover in players, staff, etc.

This is clear when discussing the continuity of a thing that is a group of people, less so when discussing a material object. (Also known as the George Washington’s Axe or Grandfather’s Knife problem.) However, if we take that the physical object has social meaning attached to it, enough that people take the trouble to preserve the object *and* replace parts of it, then we see the continuity. The lumber, canvas and rope that makes up the Ship of Theseus is less important than the group of people who perform and teach the practice of maintaining the Ship of Theseus.

In other words, it’s all about the fans.

When I go over personal identity in my 101 class, I usually present the different views to my students in terms of causal continuity. So, for instance, I might be the same person as a guy in front of this computer screen yesterday if that guy’s biological state is causally connected to my current biological state – say, that guy drink too much whiskey and I know have a bad headache. You could instead go the psychological continuity route: I am the same person as the guy in front of this screen yesterday if that guy’s beliefs, dispositions, preferences, memories, etc are causally connected to my psychological profile.

When it comes to organizations, maybe something like a “managerial continuity” view would work. A team now is the same as some team in the past if the current state of affairs of the team is the effect of decisions made by people in charge of the team in the past.

This view is nice in that it accommodates all intuitions given by the author. A team can survive changes in roster, location, name, uniform, stadium, management, etc, just as a person can survive changes to his/her body or personality.

What about fan allegiance? In my opinion, I really don’t think that fans care about rooting for the “same” team. They are more concerned about local affiliation. For many fans, following a sports team has almost as much to do with being connected to a city as it does to the team itself.

Finally, regarding the ship of Theseus, Thomas Hobbes added an interested twist to the puzzle. Proceed with the story as usual, but suppose that someone took those planks from the original ship and started to build a ship with it. At the end of the process, you have two ships. Which one is the ship of Theseus?

Suppose you say that the newly build ship, i.e. the one with the old planks, is NOT the ship of Theseus. Notice what follows. The ship of Theseus is NOT identical to the group of planks that composed it. That means that you have to allow for the fact that two distinct entities can occupy the same space at the same time. Is this metaphysically possible?

I’m sympathetic to the point of view that physical continuity is a necessary component. The new Winnipeg Jets are not the same franchise as the old Winnipeg Jets; the Phoenix Coyotes are the same franchise as the old Winnipeg Jets, despite the loss of name, location, and fanbase. The Tennessee Titans are the same franchise as the Houston Oilers; the new Cleveland Browns are not the same franchise as the old Cleveland Browns, despite the NFL’s attempt to legislate reality.

As to James’s point from Hobbes, the answer is simple: The ship which was gradually replaced is still the ship of Theseus. (Real ships have planks replaced all the time while in use and no maritime-oriented person would ever suggest that the ship changes into a different one as a result.) The second ship which was constructed out of the old pieces of the original is a *replica* of the old ship of Theseus which happens to be made of old pieces of the original, which lost their identity as “the ship” when they were removed and the ship continued to exist without them. To go back to the hockey analogy, suppose the Maple Leafs host an old-timers game and field a team composed of former players. No one would claim that the old-timers team is the real team. They used to be the real team, but the team moved on without them. Now they’re “spare parts,” arranged into a replica of what they once were.

Consider, then, what I claimed follows from what you are saying. You said that the ship with the new parts continues to be the ship of Theseus. What follows is that the ship of Theseus is a distinct entity from the planks that make it up. That means that at one point you had two distinct entities (the ship and the planks that compose it) occupying the exact same space at the exact same time. Doesn’t this seem absurd?

Notice that this is different from something like a waterlogged sponge. The sponge and the water do not occupy the exact same space at the same time. The water just takes up spaces between the sponge’s material. The case with the ship and the planks seems truly to be a case where two distinct objects occupy the exact same space at the exact same time. But how is this possible? Doesn’t this give us reason to think that the new ship is the ship of Theseus?

Nothing is particularly absurd about two entities occupying the same space and time. I believe occupying the same position in space and time is possible for distinct particles under our current best understanding of physics.

The physical bounds of structures larger than particles are difficult to even define. Even deciding what particles are part of something as complex as a ship is quite tricky.

For a less technical example, are you the same as the set of atoms that composes you? Are a monarch as a person and the monarch as the head of state the same entity? Does that change in case of abdication or coup?

In any case, there’s equivocation in the definition of entity; sometimes it refers to a snapshot at a particular moment, and sometimes it refers to something that persists as time flows. The ship before any repairs and its original components before any repairs coincide. That doesn’t imply the same about the ship after all repairs and its original components after all repairs.

The seeming absurdity with holding that two object can exist in the same space at the same time is that it allows for the possibility of an infinite number of co-located objects. If two objects can share space, then why not three? Why not four? Five? And so on.

Now suppose we had a bronze trophy. There seem to be two objects located in the same space. The trophy, and the bronze that composes the trophy. The trophy weighs ten pounds. The bronze also weighs ten pounds. We have two distinct objects with their own properties. Why doesn’t the entity filling up that particular space weigh twenty pounds?

Your comment regarding our best physics will require some form of citation.

I don’t think I’m equivocating in my use of the term “entity.” I use this as a very generic term that covers any aspect of reality. A related term might be “object.” There is nothing that is not an entity.

That said, I’m not quite sure what your point is. If it’s that co-location doesn’t seem so bad, then see my reply at the beginning of this message. Beyond that, not sure what you’re driving at.

I find nothing absurd about five coincident entities. You’d have to get to at least an uncountable infinity before it gave me pause.

Two conceptually different entities being composed of the same particles doesn’t make the particles duplicate. No human thought directly changes reality. Defining an entity is a purely mental activity. The universe and its physics are quite independent of where we draw borders.

The physics involved barely overlaps the set of things I comprehend, but you can work your way down the results at https://www.google.com/search?q=bosons+same+place until you’re satisfied that many physicists think that. To single one result out, http://www.symmetrymagazine.org/article/january-2013/bosons is a concise article by an author with powerful credentials. http://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/59929/what-prevents-bosons-from-occupying-the-same-location has a claim that Bose-Einstein condensates, which have been literally created in labs, is an example; that meshes with my paltry knowledge, but the sourcing is more tenuous.

Definitions like yours for “entity” fall apart when confronted with Russell’s paradox and its kin. Also, if you allow entities to span multiple “instants” (a troubling term itself), then the Ship of Theseus and the boards that originally composed it are no longer coterminous in James’ interpretation, as their spatial bounds are not identical for all times they both exist. (In fact, they need not have the same temporal bounds, e.g. the replica made of the boards could be burned while the Ship of Theseus was left unharmed.)

My point relates to your claims; there’s no agenda but a love of precise truth.

I meant S’ interpretation, of course.

The bronze trophy argument, which you are using to further your argument, seems to actually work against it. The trophy and the bronze which it’s made of are not distinct objects. They’re distinct concepts. There is only one object, which is why it has a finite weight.

“The ship” and “the planks that compose the ship” are two ways of looking at one object which is composed of many smaller objects. Since every object in the universe larger than a quark is made up of smaller objects (and maybe quarks are too, I’m not up on my subatomic physics), I would hope that’s not an absurd way of looking at things.

There’s another reason why the old/new ship analogy is not so easy to solve – what if, instead of replacing the ship plank by plank, it was cut in half? Take the bow of the original ship and build a 100% identical stern with new wood. Take the stern of the original ship and build a 100% identical bow.

Which one is the ship of Theseus? Neither? Both? If so, does your answer change depending on the proportion of ship that we’re cutting off? If you take 40% of the ship, and rebuild the remaining parts (60 old / 40 new and 40 old / 60 new), does it matter?

Cutting a ship in half (and removing half) is a violent act of discontinuity. I would argue that the result is that neither of the ships are the ship of Theseus anymore. Suppose an amoeba undergoes reproductive fission. Now you have 2 amoebas. Which is the original? Neither.

Now, as to the question of 60-40 or whatever, I don’t have a pat answer, but I would propose that any time you remove a large enough chunk that the ship is not able to adequately function as a ship, even in a crippled state, and then replace that chunk with new material, you have a different ship. Plutarch understood this intuitively, which is why he posited that the ship was replaced one plank at a time.

Overall I loved this article. I am not a sports fan but I have been intellectually intrigued before at the idea of a sports team changing cities and/or names. I do tend to agree with the interpretation of the article, being that it is a team’s name and legacy and fanbase that make it, not its members. There was an interesting point made early on in the article that was never touched on again though, which is that even though the Toronto Maple Leafs have changed players and management etc many times since ’68, they tend to play similarly and end up in a similar spot in the rankings. Why is this? What is it about the Maple Leafs as an abstract idea, outside of its constituent parts, that causes it to be a similarly-playing-and-ranking team year after year? I am reminded of a scene in the movie Moneyball, where they talk about the Oakland A’s losing streaks. They talk about how because of the size of the team and the city and the lack of money available, that they will never be able to afford the big A-list players and will thus continue to stay at their level, competitively speaking. Despite many years of changing the team piece by piece, they were never able to get out of their collective loser identity, because of outside factors like a lack of resources. This is an interesting factor to consider for this article.