[Enjoy this guest post from frequent contributor Richard Rosenbaum! – Ed.]

How often has this happened to you: you’re going about your life, minding your own business, when some kind of cybernetic construct appears out of the mists of time to destroy you, to remake the future into the hellish nightmare that your absence from the world is intended to provoke. Dick move, right? Yet if you live, as I do, mainly within the global mediascape, you’re probably fairly familiar with this course of events. It seems to occur pretty frequently. Now, sure, robots from the future are always out to kill you – but the question that arises is this: does that really make them evil?

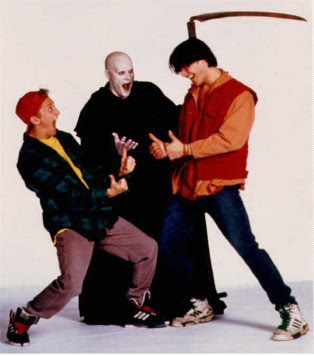

The best way to answer this question is, of course, with an in-depth look at that classic of modern cinema Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey. The reason that Bogus Journey is the ideal model for exploration of this question, rather than, say, Terminator 2, which has in many ways a very similar plot, is not only because Bogus Journey is the superior film, but also because it contains an almost scientific distribution of variables with which we can compare and contrast: Good Human Bill & Ted, Evil Robot Bill & Ted, and Good Robot Bill & Ted. We’ll examine the problem by first looking at the awesomely unsettling concept of Philosophical Zombies.

“Philosophical Zombie” is an unfortunately imprecise term for those of us more familiar with the pop culture sort of zombies that are generally portrayed as mindless animated corpses. Usually, once you know that there are zombies about, it’s not too hard to determine who’s one of them and who isn’t; you don’t get a lot of “No, don’t shoot me, shoot him – he’s the zombie!” It’s pretty obvious that the dude with his skin falling off, emitting preverbal groans while munching on your corpus callosum is the zombie.

The Philosophy of Mind kind of zombies are a more complicated matter. They’re completely identical in every way to a regular person, except that there’s no subjective quality to the character of their experience. That is, they have no consciousness. Physically, they’re indistinguishable from a human being, down to every atom. But there’s no inner life, no apperception, no meta-awareness. No soul, if you like. There’s literally no way to tell that a Philosophical Zombie isn’t human – you can examine their brain as closely as you want, and will discover no indications of an absence of consciousness. You can even ask them – are you conscious, or are you a zombie? And they’ll tell you that they’re fully human and not a zombie; not because they’re trying to avoid getting shotgunned in the head, but because they genuinely don’t know that they’re a zombie. They don’t really know anything, they’re only responding to stimulus based purely on physical reactions.

That’s why it’s more apt to compare them, rather than to horror-style undead zombies, to robots. The evil killer robot trope is an extremely popular one in science fiction, precisely because of how it relates to questions of Philosophy of Mind: What is a person? Do you have to have a body made of meat in order to possess a soul, or will metal do? Is there any difference between a person’s desire to have a nice piece of toast and a toaster’s “desire” to burn some bread inside of it?

Of course, science fiction robots aren’t a perfect analogue for Philosophical Zombies for two main reasons. One, they’re not atom-by-atom duplicates of a person; in general, they tend to be visibly non-human, at least after you get under their skin (the most notable exception to this being Blade Runner, wherein the Replicants look so completely human that they even bleed when you shoot them – and not Alien-style creepy white android stuff, but human-looking red blood). And two, they usually know that they’re robots, and are frequently upset at the second-class citizen treatment they receive at the hands of their human creators (Blade Runner is, again, a partial subversion of this; most of the Replicants know what they are and that they have built-in termination dates, although the more advanced Nexus-7 models are implanted with false memories that cause them to believe they are human). But for the purpose of this discussion they’re close enough, because the question we’re trying to answer is: does functional identity equal total identity? Or: are evil killer robots from the future actually evil, or are they just doing what their programming tells them?

The trick of this is a side-effect of the Philosophical Zombie thought experiment. The purpose of the scenario was originally to determine whether or not consciousness could be a completely physical phenomenon. Australian philosopher David Chalmers formulates it this way: it’s possible to conceive of a being that’s completely identical to a human and yet does not possess consciousness, behaving purely in a physically deterministic way. That is, the idea of philosophical zombies doesn’t seem to violate any logical principles (whether or not they are actually possible in reality is a different question, but also isn’t important for the purpose of this experiment). The consequence of this, though, is that since purely physical processes don’t seem to necessitate the existence of consciousness, the existence of consciousness therefore cannot logically be a physical quality; it must be something else. Or, in Chalmers’s parlance, consciousness does not logically supervene on the physical.

All this is relevant to the speculative fiction question of whether or not androids dream of electric sheep, but what does it have to do with evil killer robot apologetics? This:

How are we meant to decide if Evil Bill & Ted are actually evil? The main thrust of Chalmers’s zombies argument is that the only difference between a human with consciousness and a philosophical zombie is simply consciousness; in every other way they are intended to be identical. Our whole moral basis for good and evil (or praise and blame) relies on the idea that we’re in control of our behaviour – that is, that we could have decided to do something different. That’s the reason we don’t assign moral blame to, say, a meteorite that lands on your head even though the effect might be the same as if I had thrown a rock at you. Because the meteorite didn’t have a choice in the matter – it was purely the laws of physics that dictated its behaviour, whereas, seemingly I could have chosen not to throw that rock at you even though you were being a total dick. And it’s the same reason we have a concept in law that people can sometimes not be responsible for their behaviour – certain types of mental illnesses or other extenuating circumstances can be seen as having interfered with a person’s free will, so that they really couldn’t have done things differently.

So it would seem like Evil Bill & Ted could only be evil if they have free will, which appears to be a consequence of consciousness (because if the philosophical zombie’s behaviour is entirely physically dictated, then it really can’t do anything differently even if it’s doing all the same things as its conscious human counterpart, who hypothetically could even if the outcome was the same). Are the robots conscious, then? Do they have free will or not? The movie seems to provide evidence both for and against the interpretation that the robots are responsible for their own behaviour.

First of all, they are not only canonically called “evil” in the movie, but refer to themselves as evil. They call each other Evil Bill and Evil Ted, and just as the real Bill and Ted call the mechanical duplicates “Evil Robot Usses,” the robots call their biological counterparts “Good Human Usses.” So they do seem to consider that the only differences between themselves and the real Bill and Ted are that one pair are robots and the other are humans, and that one pair are evil and the other good – they certainly appear to be making moral judgments about themselves by the same criteria the people in the movie are judged. It’s easy, though, to argue that all the Bills and Teds are just using the terms “good” and “evil” colloquially, and don’t really mean to be making metaphysical assertions.

The creator of the robots, De Nomolos, seems to imply that his creations have at least some degree of free will and responsibility for their actions. At one point he says, in a very annoyed sort of way, “I hate them, and I hate the robot versions of them.” It would hardly make sense to hate something that wasn’t in control of its own behaviour – although, again, it’s unfortunately not that simple. I hate centipedes with the force of a million hydrogen bombs, but that’s just me being a centipede-racist; I don’t actually think that they have any significant degree of consciousness. De Nomolos could just be irritated by the robots’ behaviour. However, a couple of other somewhat subtler things make it seem like De Nomolos could be implying that he gave them consciousness and/or free will. The context of the scene in which he declares his hatred for his creations is that they’ve already killed Good Human Bill and Ted, and are now just kind of messing around in B&T’s apartment, breaking stuff, playing basketball with their robot heads, and acting generally obnoxious, as evil robots are wont to do. De Nomolos contacts them and tells them to quit goofing off and get back to the plan – wrecking Bill & Ted’s legacy, not just by killing them, but then taking over their lives.

Now, the fact that De Nomolos has to keep contacting them from the future and reminding them to get back to the mission says something. They’re robots, but clearly not mindless robots. Their inclination is to be jerks, but the specific ways that they can be jerks appears to be up to them. De Nomolos doesn’t actually control them in that sense; they are to some extent autonomous.

You can say, sure, they have some degree of autonomy, but that doesn’t make them conscious or responsible for their behaviour. And even Evil Bill & Ted themselves make this argument; when De Nomolos tells them that he hates them, their response is, “You programmed us!” Obviously attempting to foist the responsibility for their actions away from themselves and back onto their creator. This is a really interesting and somewhat convincing argument, actually. If all our behaviour is at the mercy of the deterministic physical processes of our bodies and brains – and nobody, I think, at least no materialist, currently subscribes to the theory that physical processes are indeterminate (probabilistic, yes, but not indeterminate), then we’re ultimately not in control of our actions. This is, going back to Chalmers, one of the major reasons that he ends up rejecting pure physicalism. Evil Bill & Ted are telling De Nomolos that they can’t be blamed for their behaviour because they’re not in control of it, it was determined for them ahead of time by the way they were built – but if you think about it, isn’t that exactly what someone evil would say? They’d try to dismiss responsibility for their actions so they were free to do anything they wanted to – and they clearly want to do things that they were not specifically programmed to do. Yes, they also want to do things that they were programmed to do, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re not making a free choice decision to do it anyway.

The argument could equally be made that the Good Robot Bill & Ted that Good Human Bill & Ted build once they come back to life (or, rather, have the Martian scientist Station construct for them out of stuff from a hardware store) are not strictly speaking good either, precisely because they’ve been programmed to be “good,” just as Evil Bill & Ted have been programmed to be “evil.” But think about this, then: are Good Human Bill & Ted good? By all accounts, we have to say that they are. Not just because they’re humans – and we, also being humans who have consciousness and feel that we have free will, project those assumptions onto them as well – and not just because their evil robot counterparts explicitly refer to them as such, but because of what happens in the movie after they are killed.

After escaping the Grim Reaper, but being subsequently banished to hell while trying to contact their families, they summon the Grim Reaper again and beat him in several games for the opportunity to return to life. They know that if they go straight back to Earth, the robots will just kill them again, and so they enlist the Grim Reaper’s aid, who helps them sneak into Heaven and ask for God’s assistance in building the Good Robot Thems. Which God provides. The world of Bill & Ted includes an afterlife with clearly distinguished reward and punishment for behaviour. True, Bill & Ted are not sent to hell or heaven strictly because of how they lived their lives, however they do manage to convince God to help them – and if anyone has free will, I think we’ve got to say that it’s God.

When Evil Robot Bill & Ted finally have their heads punched off by Good Robot Bill & Ted – what happens? Do their robo-souls go to hell as punishment for their murder of Good Human Bill & Ted and their various other despicable acts? Or do they simply cease to exist because, as robots, they had no consciousness or responsibility for their behaviour to begin with? The movie doesn’t tell us – although, in a deleted scene, in which De Nomolos is also killed, we get to see that his personal hell is that he must now spend eternity with the Evil Bill & Ted Robots that he created. Is that the robots’ punishment as well? They never seem to experience anything other than a sort of giddy malice throughout the movie – they’re not even particularly bothered when it becomes obvious that their demise is imminent. They salute their good human counterparts with a resigned, “Catch you later, Bill and Ted,” and then get their heads punched off. What would constitute punishment for such creatures, anyway?

Like the topics of morality and consciousness themselves, Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey offers no easy answers, only more and more difficult questions. Maybe that’s exactly why the simplicity of Wyld Stallyns’s message resonates so, why it eventually spreads across the world and brings peace and serenity to everyone who hears it: Be excellent to each other, and party on, dudes.

…and if anyone has free will, I think we’ve got to say that it’s God.

Could it not be argued that God’s purported attributes (at least in the big three monotheistic traditions) rather militate against this conclusion? Being omnibenevolent and omniscient together, for example, seems to push towards God knowing in all circumstances what is best to do and then by virtue of his perfect goodness being forced to do it. After all, if God chose to do something else (or nothing at all), he would lose claim to the notion that he is all-good, since he knew what is right to do and did something else instead.

The only escape hatch I can see is if the perfectly good course of action for a given circumstance is multiply realizable, but that causes problems akin to Buridan’s Ass; if two possible courses of action are equally good from the perspective of an entity that knows everything, on what grounds does that entity choose between them?

Before we can make that argument, we have to define what we mean by “omnibenevolent”. Certainly, we don’t mean “bound to do what a human would consider the ‘right thing'”; otherwise, we would expect things like advance warning of natural disasters. One often-invoked possibility is to take God’s actions as defining good. That is, God does not do a thing because it is good, but rather a thing is good because God does it. If you go that route, then there is plenty of room for the deity to have free will.

That leads to the Euthyphro problem of what is being defined as good as ultimately being arbitrary. (If God defines good, how did God determine what he defined would match the concept? If the definition preexists, he is merely explicating or discovering the Good, while if he defines it, then He cannot resort to any concept to deflect the argument that what he chooses as good are merely His preferences.)

Of course these questions become much simpler if you think that consciousness is a physical process in the brain and is therefore not special. It may lead to uncomfortable conclusions like that free will and consciousness are illusions, that nothing separates us from robots other than complexity, and that our actions are determined ultimately by the boundary conditions of the universe, but it does solve many tricky philosophical problems.