One of the most common and understandable complaints about HBO’s gangster drama Boardwalk Empire is that its notional protagonist, Nucky Thompson, isn’t very good at being a gangster. He’s not very ruthless with his enemies, allows himself to get outmaneuvered by younger and poorer factions, and succumbs to sentiment once too often. In S2 alone, he’s engaged in the questionable strategy of “upgrading” his state-level voter fraud charge to a federal Mann Act violation, thus allowing him to call in a favor with the Attorney General. This backfires, as you’d think it might. While we don’t expect a gangster to pull off every plan with clockwork precision, we’d hope that he wouldn’t look so shocked when his enemies conspire against him.

But I still love Boardwalk Empire. Here’s why:

Jimmy Darmody lays out Nucky’s dilemma in the first episode of S1, after Jimmy forces Nucky’s hand by ambushing a liquor convoy that was on its way to Arnold Rothstein. “You can’t be half a gangster, Nucky,” Jimmy says. “Not anymore.” A little on the nose, sure, but that’s the way Boardwalk Empire operates.

Nucky starts the series as the unofficial king of Atlantic City. Perpetual treasurer for Atlantic County, he makes sure everyone pays for every privilege he can offer. He has advanced about as far in polite society as he can, short of becoming Senator (and, as Frank Hague notes to Nucky in S1E6, “Family Limitation,” Senators come and go). While he can’t accrue much more power, he can certainly accrue more wealth. He recognizes the opportunity that Prohibition affords him, turning the free consumption of liquor into a privilege that he can collect illicit rents on.

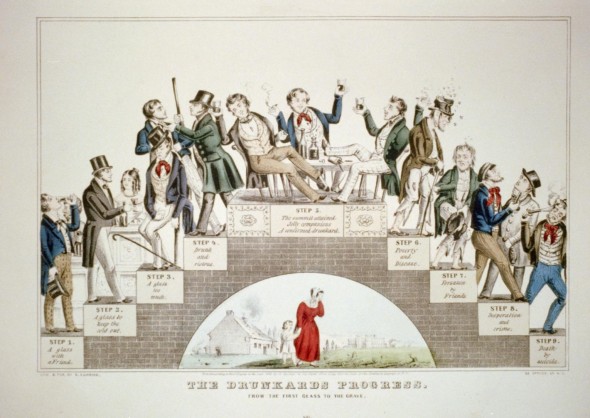

The theory of moral sentiment, and how to drown it.

The problem is that Nucky is going from the polite world of white collar crime to the gritty world of the mob when he makes this move. And Nucky, despite his attitude, isn’t a mobster. He’s a grafter, a games-player and a power broker, skill sets that are all critical for mob bosses, so it’s easy to get confused! But Nucky is a politician. He’s risen in the world of polite crime, where 13-year-old girls get brought before the bosses of the city because no one will miss a 13-year-old girl.

Nucky lays this out best when negotiating with the unofficial head of the midget performers’ union in S1E5, “Nights in Ballygran.” Rather than double the performers’ wages from $5 a head to $10, Nucky tells the negotiator that he’ll go to $7 and give the negotiator $12. The extra three bucks a head, Nucky keeps. He keeps money in his pocket and the midgets get less than they could probably earn.

We see similar examples in S2E8, “Two Boats and a Lifeguard,” where Nucky gets Chalky White to foment a strike among the black laborers in Atlantic City. This has the effect of putting dozens, if not hundreds, of men and women out of work (in S2E9, “Battle of the Century”) and in the hospital (S2E10, “Georgia Peaches”). Nucky’s plan is obvious: to make Atlantic City under Jimmy Darmody’s reign unlivable. He scores while Chalky and his constituency suffer.

Polite crime benefits the upper class at the expense of the underclass. But to move illegal liquor, Nucky has to act like a gangster. And gang crime benefits the underclass at the expense of other underclasses – or at the expense of the upper class.

Study the history of the mob in America, any mob, and you’ll find organic ethnic networks that arise for mutual protection. The Mafia are the most famous example. While they were a power of their own in Italy, the Mafia migrated to America as a way for Italian communities to look out for each other. The courts wouldn’t give a fair shake to guineas fresh off the boat, so they banded together to address their own grievances. Eventually, these informal gangs grew in scope and power to the point that they could touch the lower rungs of the ladder of wealth. At this point, these underclass mobs were like a ruling class faction of their own. Ditto the Irish mob (more of a presence in Boston than New York but still familiar to an American audience). Ditto black street gangs. Ditto Jewish gangsters.

(In fact, that’s the arc that Deadwood told over its three too-short seasons: how a mob turns into a respectable government through the agglutination of tradition and ritual. You fake it until you make it. But that’s another article)

The only security men can have for their political liberty consists in their keeping their money in their own pockets, until they have assurances, perfectly satisfactory to themselves, that it will be used as they wish it to be used, for their benefit, and not for their injury.

The common element in all cases is an ethnic minority that can not gain admission to the upper class. If you could gain entrance – if you could golf at Columbia Country Club and send your kids to Princeton – you wouldn’t need to pay the local heavy five bucks a month. But the normal opportunities for advancement within the hierarchy aren’t available to you. Instead, you create your own hierarchy in the ghetto: bosses, lieutenants, enforcers, runners and the like. Just as a labor union concentrates the efforts of a thousand disparate employees to negotiate on par with a firm, so do gangs concentrate the efforts of immigrants to negotiate with the existing political machine.

Additionally, gangs are able to close ranks through ethnic barriers. It’s not hard to keep power concentrated: just share it with only the people you know or get introduced to. Jimmy can’t rise to kingship of Atlantic City until he gets the approval of “the men who built Atlantic City,” including Leander Whitlock (S2E2, “Ourselves Alone”). There’s little chance Whitlock will ever shake hands with Chalky White.

Ethnic gangs can lock out intruders as well through language and cultural barriers. If everyone in Little Italy speaks Italian, a WASP cop won’t be able to police them. It’s easy to keep illegal business secret, and criminal gangs rely on secrecy in order to survive. This even helps gangs that go to war with each other: Chalky White survives an attempted hit by the d’Alessio brothers (S1E3, “Broadway Limited”) because they can’t tell black men apart. Similarly, Manny Horwitz is able to leverage his relationship with “Mickey Doyle” (originally a Polish Jew) to make end runs around the Darmody syndicate.

(Not every ethnic gang feuded, mind you. The Italian mobs in New York, Chicago and New Orleans were among the first in the country to sponsor black entertainers and introduce black styles of music, such as jazz, to the white masses. And we’ve already seen that Charlie Luciano and Meyer Lansky have no problem breaking challah together)

This is the world that Prohibition created.

Contemporary audiences underestimate how prevalent drinking was in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Water treatment was still in its infancy, with sand filtration and chlorination only coming into widespread use in the 1890s. Drinking water for refreshment wasn’t common in the cities (even the teetotaller Van Alden goes for cold buttermilk). People drank beer all the time. Laborers drank beer on the job. Wine was served with dinner. Liquor was offered to every guest. Drinking at all hours of the day was so prevalent that, well, a popular amendment to the Constitution banning the sale, manufacture and transport of alcohol became politically feasible.

This was the 'crying eagle over the World Trade Center wreckage' of its day.

Clamping down on such a widespread habit simply shifts its costs around. The price of a drink now includes the price of keeping it secret, finding an illicit supplier and paying off the authorities (or rebuilding after the occasional raid). These can be considered capital investments or rents, and not every entrepreneur can handle them. If your business required a major new form of investment overnight – say, every email you sent had to have 128-bit encryption – you might go out of business rather than adapt.

But you know who’s uniquely suited to keeping secrets, acquiring goods off the books and dodging the authorities? Ethnic gangs.

The problem that Nucky is discovering, over the course of the first two seasons, is that the gangs are the only ones who can move booze. As a social climber, Nucky wants to distance himself from his impoverished roots – his abusive father; his crowded childhood home, which he burns to the ground; his crazy first wife. While he’s Irish, he belongs to a staid, respectable class of Irish, who get drunk behind closed doors and all hold respectable positions in the community. Not for him the rough and ready style of Margaret’s family, living in Brooklyn (S2E7, “Peg of Old”).

It’s telling that Nucky has to go to Ireland (S2E9, “Battle of the Century”) to get some leverage in his war with the Darmody syndicate. He has to press his connections with the old country, involving himself in an ethnic feud that he cares little for otherwise. But that’s where power flows from now: knots of like-minded ethnicities banding together. Trading favors clearly doesn’t do it: look how the Attorney General repays him for putting Harding in the Oval Office. Look how his aldermen repay him for his years of ensuring a smooth flow of graft. Hell, look how Jimmy repays him for a lifetime of support.

Stand up straight.

The reason people have a hard time with Nucky Thompson and Jimmy Darmody (on whom more in a moment) as protagonists in Boardwalk Empire is that neither of them act like the gangsters we recognize. There are few threats, and even fewer cold-blooded killings. When Jimmy caps a man for a smart remark (S1E10, “Emerald City”), Nucky looks at him in disgust; Jimmy shrugs in a near apology. Every rule the jaded cineaste can recite from heart – nothing personal, strictly business; keep your friends close and your enemies closer; never get high off your own supply – these two knuckleheads break.

The confusion comes from our misinterpretation, though.

People who are dissatisfied with Nucky as a gangster are often looking for him to fill in the traditional rise-to-power narrative. But that’s not Nucky’s story. Nucky already has power. He’s the king of Atlantic City. This is the story of how Nucky loses power through Prohibition – how he and his pals in Trenton, D.C. and Chicago let a cheap intoxicant become a rich resource in the hands of America’s underclass. Signing the Volstead Act was signing the death warrant for the Gilded Age political machine. Now power lay in the hands of the Italian mobs, the Jewish syndicates and Irish laborers.

The ground is being pulled out from under Nucky’s feet by the tide. Even if he wants to pocket some of the bottles that come in and get rich off the proceeds, he can’t possibly scoop up them all.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A9DCLv_6e5c

What about Jimmy, then? He seems primed for a classic rise-to-power narrative, right? Unfortunately, no. Jimmy, like a lot of other sensitive artists who went to war, has joined the Lost Generation. He’s a man without a country. He starts out working for the ersatz-WASP Nucky Thompson, joins the Italian mob in Chicago, then ends up doing deals with Manny Horwitz and Meyer Lansky in the Midatlantic. He drifts from one ethnic gang to another because he has no real roots of his own. He was raised with a father in prison and a warped, dissipated mother; he lost his innocence in the most brutal war of the Twentieth Century (four-way tie for 1st); and he casts aside every friend he gets in the name of … what, ambition? envy? a death wish?

Jimmy’s not likely to survive through Prohibition. He’s a man without a country, and this isn’t the time for a self-made man. And Nucky’s going to watch the beach crumble beneath him because he’s signed all his power away. Relying on striking black laborers and fine Irish whiskey may get him back in office, but it also gives two different factions a lever to use against him.

The 20s were a period where the Old World and the New ground against each other like tectonic plates. It was the era that gave birth to the gangster. Boardwalk Empire shows us that birth, and all the blood it entails.

Great column. Especially telling is the choice of the word “Empire” in the title of the series. There are two things empires do. Rise and fall. Stories about the rise of empires aren’t nearly as interesting as those of the fall, so we ought to have seen from the very beginning where this story was eventually leading.

I think there’s time yet for Nucky to become a proper gangster, but the column is absolutely right that the show is about the birth of the modern gangster. It’s also about how prohibition of a substance that is not intrinsically evil (witness Van Alden’s malum in se vs. malum prohibitum discussion at the lunch counter) cultivates crime, violence, and misery. At the beginning of the series, Nucky Thompson is a venal but basically peaceful man who works as a stabilizing presence in AC. He is thoroughly corrupt, but in a way that generally doesn’t prevent people from getting on with their daily lives. It takes Prohibition of drugs — err, I mean booze — to turn Nucky into a murderer. His existing graft is why we believe his world could have existed, but the illegal alcohol is that makes it a world we would have been scared to live in.

Reading this column after watching the season finale was really interesting! It seems now that this final episode was Nucky cementing himself as a “real Gangster” and reclaiming all the power, and maybe more, that was taken from him. But at what cost? Nuck has always claimed that the only thing he wants in this world is a real, loving family. But as Jimmy said to him in that fateful scene in front of the statue, he’s going to slowly degrade and lose everyone around him. We can already see it starting in the eyes and actions of his new wife. And I suspect that Esther Randal will not be gone for long.

While I was a bit surprised by the season finale of season 2, I did expect Nucky to make that choice. I bet most people where expecting Nucky to be Tony Soprano from Ep1 S1. And really what this season is, a birth of a gangster.

And it is similar to The Wire. In the wire every character over 20 years old complained that the criminals of today did not have the code and honor of yesterday.

I thought the birth of a gangster symbolism of the finale worked fine, and it was as good a time as any to lose Jimmy. That said, something felt oddly rushed about the whole thing, and I especially thought that Jimmy’s wartime psychological damage was (a) not fleshed out enough, and (b) severely undercut by the damage he suffered/self-inflicted his last night at Princeton. I almost would have preferred he told Nucky, “I died before I even got into that trench.” Tacky pun not intended, but enthusiastically embraced.

Tangentially, isn’t it also interesting that one of the marks of a good show is that we think it worthwhile to nitpick any particular moment that individually rubbed us the wrong way.